4. Khalaf REV by Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Futuro Sapere

Futuro sapere “Poiché gli è offizio di uomo buono, quel bene che per la malignità de’ tempi e della fortuna tu non hai potuto operare, insegnarlo ad altri, acciocché, sendone molti capaci, alcuno di quelli, più amato dal cielo, possa operarlo” Machiavelli, Discorsi, ibro !!, introduzione !n questa sezione pubblichiamo e pubblicheremo saggi di giovani studiosi che presentano le loro ricerche in corso o gli esiti parziali del" le stesse# $’altra parte, è da sempre nello spirito della nostra rivista far circolare testi provvisori e ipotesi di lavoro ancora da sottoporre a ultime verifiche e perciò bisognose di confronti e suggerimenti. Il pensiero politico di Jacopo Aconcio Elisa Leonesi Qualche notizia introduttiva &acopo 'concio nasce a (ssana, vicino a )rento, agli inizi del *in" quecento# $opo aver intrapreso gli studi di giurisprudenza, pratica l’attività di notaio a )rento, dove assiste alla prima fase del *onci" lio# $al +,,- presta servizio presso la corte del futuro Massimiliano !! e nel +,,. diviene segretario del *ardinale *ristoforo Madruzzo, nuovo governatore dello /tato di Milano# a decisione di aderire al" la religione riformata costringe però 'concio all’esilio e, dal giugno 1557, egli soggiorna nelle città di 1urigo, 2asilea, 3inevra e /tra- sburgo# 3iunto in /vizzera, gode di un’immediata notorietà tra co" loro che circondano il *urione e il *astellione e conosce sicuramente l’Ochino, il 4ermigli, il 4ergerio e probabilmente anche elio /oci- ni# 5a contatti con i pastori zurighesi &ohannes 6olf, 37alther, /imler e 8risius -

074-Sant'onofrio Al Gianicolo.Pages

(074/05) Sant'Onofrio al Gianicolo Sant'Onofrio al Gianicolo is a 15th century monastic and titular church in Trastevere, on the Janiculum. The dedication is to St Onuphrius, a 4th century Egyptian hermit or Desert Father. He was popular in the Middle Ages, and an iconographic representation of him as a naked man with a long beard preserving his modesty can still be found in churches in Europe. History The monastery is not an ancient foundation. What was here before the 15th century was a holm-oak wood on the northern end of the Janiculum ridge, in which Blessed Nicholas of Forca Palena (1349-1449) founded a small hermitage in 1419. He had been born in a mountain hamlet called Forca near Chieti, and worked as a diocesan priest of Sulmona at Palena before migrating to Rome around the year 1404. There he joined an informal group of penitents who had gathered around one Rinaldo di Piedimonte at the church of San Salvatore in Thermis (now demolished). Nicholas took over as priest in charge of the church and leader of the group, and thus began a new religious congregation which became known as Heremitae Sancti Hieronimi. (The patron was St Jerome.) He founded a community in Naples in 1417, Santa Maria delle Grazie a Caponapoli, and then this hermitage in Rome with the help of Gabriele Cardinal Condulmer, who became Pope Eugene IV in (074/05) 1431. He had made friends with Blessed Peter Gambacorta, a hermit at Montebello near Urbino who (according to the legend) converted a band of robbers and so founded the Fratres Pauperes Sancti Hieronimi in 1380. -

Collecting and Representing Saxon Identity in the Dresden Kunstkammer and Princely Monuments in Freiberg Cathedral

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE International Projects with a Local Emphasis: Collecting and Representing Saxon Identity in the Dresden Kunstkammer and Princely Monuments in Freiberg Cathedral A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Daniel A. Powazek June 2020 Thesis Committee: Dr. Kristoffer Neville, Chairperson Dr. Randolph Head Dr. Jeanette Kohl Copyright by Daniel A. Powazek 2020 The Thesis of Daniel A. Powazek is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS International Projects with a Local Emphasis: The Collecting and Representation of Saxon Identity in the Dresden Kunstkammer and Princely Monuments in Freiberg Cathedral by Daniel A. Powazek Master of Arts, Graduate Program in Art History University of California, Riverside, June 2020 Dr. Kristoffer Neville, Chairperson When the Albertine Dukes of Saxony gained the Electoral privilege in the second half of the sixteenth century, they ascended to a higher echelon of European princes. Elector August (r. 1553-1586) marked this new status by commissioning a monumental tomb in Freiberg Cathedral in Saxony for his deceased brother, Moritz, who had first won the Electoral privilege for the Albertine line of rulers. The tomb’s magnificence and scale, completed in 1563, immediately set it into relation to the grandest funerary memorials of Europe, the tombs of popes and monarchs, and thus establishing the new Saxon Electors as worthy peers in rank and status to the most powerful rulers of the period. By the end of his reign, Elector August sought to enshrine the succeeding rulers of his line in an even grander project, a dynastic chapel built into Freiberg Cathedral directly in front of the tomb of Moritz. -

In Hans Jakob Fuggers's Service

Chapter 3 In Hans Jakob Fuggers’s Service 3.1 Hans Jakob Fugger Strada’s first contacts with Hans Jakob Fugger, his chief patron for well over a decade, certainly took place before the middle of the 1540s. As suggested earlier, the possibility remains that Strada had already met this gifted scion of the most illustrious German banking dynasty, his exact contemporary, in Italy. Fugger [Fig. 3.1], born at Augsburg on 23 December 1516, was the eldest surviving son of Raymund Fugger and Catharina Thurzo von Bethlenfalva. He had already followed part of the studious curriculum which was de rigueur in his family even before arriving in Bologna: this included travel and study at foreign, rather than German universities.1 Hans Jakob, accompanied on his trip by his preceptor Christoph Hager, first studied in Bourges, where he heard the courses of Andrea Alciati, and then fol- lowed Alciati to Bologna [Fig. 1.12]. Doubtless partly because of the exceptional standing of his family—the gold of Hans Jakob’s great-uncle, Jakob ‘der Reiche’, had obtained the Empire for Charles v—but certainly also because of his per- sonal talents, Fugger met and befriended a host of people of particular political, ecclesiastical or cultural eminence—such as Viglius van Aytta van Zwichem, whom he met in Bourges and again in Bologna—or later would ascend to high civil or ecclesiastical rank. His friends included both Germans, such as the companion of his travels and studies, Georg Sigmund Seld, afterwards Reichs- vizekanzler, his compatriot Otto Truchsess von Waldburg, afterwards Cardinal and Prince-Bishop of Augsburg [Fig. -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

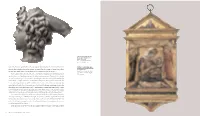

Lord, in the Piazza Are Works by Donatello and the Great Michelangelo, Both of Them Men That in the 17

16. Benvenuto Cellini, Head of Medusa (sketch model for a statue of Perseus). Bronze, 13.8 cm high. Florence, c.1545–50. V&A: A.14–1964 lord, in the Piazza are works by Donatello and the great Michelangelo, both of them men that in the 17. After Donatello, Virgin and Child (frame probably painted by glory of their works have beaten the ancients; as for me I have the courage to execute this work to Paolo di Stefano). the size of five cubits, and in so doing make it ever so much better than the model.’115 Painted stucco in a wooden frame, 36.5 20.2 cm. Florence, c.1435–40. Yet for all that, it was only in the sixteenth century that the intellectual and individual qualities of V&A: A.45–1926 an artist came to be of significant concern to the patron, purchaser or owner. Prior to that, it seems that an artist’s mastery of a particularly sought-after technique or their extraordinary skill were defining criteria. Thus, to emphasize the extent to which Cistercian patrons were prepared to honour God, it became something of a topos in twelfth- and thirteenth-century accounts of monastic patronage that artists had been brought ‘from foreign parts’ to work on Church building projects because the particular skills they possessed were unavailable locally.116 Aubert Audoin, cardinal and former bishop of Paris, sent for potters from Valencia to produce lustred tiles for his Avignon palace in the late 1350s, because at that date the technique of producing such a golden glaze was known only in the Islamic world.117 The function of an object also continued to outweigh considerations of the identity of its maker. -

I Codici in Scrittura Latina Di Alessandro Farnese (1520-1589) a Caprarola E Al Palazzo Della Cancelleria Nel 1589

This is an electronic reprint of the original article. This reprint may differ from the original in pagination and typographic detail. Author(s): Merisalo, Outi Title: I codici in scrittura latina di Alessandro Farnese (1520-1589) a Caprarola e al Palazzo della Cancelleria nel 1589 Year: 2016 Version: Please cite the original version: Merisalo, O. (2016). I codici in scrittura latina di Alessandro Farnese (1520-1589) a Caprarola e al Palazzo della Cancelleria nel 1589. Progressus, III(1). http://www.rivistaprogressus.it/wp-content/uploads/outi-merisalo-codici-scrittura- latina-alessandro-farnese-1520-1589-caprarola-al-palazzo-della-cancelleria-nel- 1589.pdf All material supplied via JYX is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, and duplication or sale of all or part of any of the repository collections is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for your research use or educational purposes in electronic or print form. You must obtain permission for any other use. Electronic or print copies may not be offered, whether for sale or otherwise to anyone who is not an authorised user. I codici in scrittura latina di Alessandro Farnese (1520-1589) a Caprarola e al Palazzo della Cancelleria nel 1589 OUTI MERISALO Anno III, n. 1, luglio 2016 ISSN 2284-0869 ANNO III - N. 1 PROGRESSUS Abstract This article analyses the contents of the manuscripts in Latin script found at the Villa Farnese of Caprarola and the Palazzo della Cancelleria of Rome at the death of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese (1520-1589). They were inventoried by Claudio Tobalducci, librari - an to the Cardinal; the inventories were edited by Francois Fossier. -

Dissimulation and Deceit in Early Modern Europe

Copyrighted material – 978–1–137– 44748–7 Selection and editorial matter © Miriam Eliav- Feldon and Tamar Herzig 2015 Remaining chapters © Contributors 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6– 10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978– 1– 137– 44748– 7 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. -

The Council and the “Papal Prince”: Trent Seen by the Italian Reformers*

The Council and the “Papal Prince”: Trent Seen by the Italian Reformers* Diego Pirillo Introduction In November 1550, having left Italy the previous year to embrace the Reformation, the former bishop of Capodistria Pier Paolo Vergerio published a pamphlet against Julius III, who, under pressure from Charles V, intended to reopen the Council in Trent.1 The pamphlet, one of several launched by Vergerio against the council, was dedicated to Edward VI. The English king had recently welcomed the two prominent Italian reformers Peter Martyr Vermigli and Bernardino Ochino, who had arrived in England at the invitation of the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer, himself determined to summon a general Protestant council in opposition to the one that had just begun in Trent.2 From his Swiss exile, Vergerio attentively followed not only his fellow reformers abroad but also those still in Italy. By opting for the vernacular over Latin, he intended to reach a wide audience of Italian readers who remained undecided on whether to break off from the Roman Church and leave Italy or to stay and compromise with Catholic orthodoxy. A skillful pamphleteer, Vergerio knew very well that the purpose of “adversarial propaganda” was to create stereotypes and that, by contrasting a positive set of ideas with its negative antithesis, he could target the “uncommitted,” situated between the two extremes.3 Thus, Vergerio outlined a sharp opposition between the supporters of the Reformation on one side and the Roman Antichrist on the other, aware that any third alternative would have undermined the efficacy of his communicative strategy. -

Combined Bibliography

Combined Bibliography Abbreviations DNB Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ed. by H.C.G. Matthew and Brian Harrison, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004); online edition edited by Lawrence Goldman, 2006–2008. DSB Dictionary of Scientific Biography, ed. by Charles Coulston Gillispie (New York: Scribner, 1970–1990). Primary Sources Agricola, Georgius. 1556. De Re Metallica. Basel: H. Frobenium et N. Episcopium. ———. 1950. De Re Metallica. ed. and trans. Herbert and Lou Henry Hoover. New York: Dover Publications. Alberti, Leon Battista. 1485. De Re Aedificatoria (1452). Florence: Nicolai Laurentii. ———. 1988. On the Art of Building in Ten Books. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Apianus, Peter. 1533a. Cosmographicum liber. Antwerp: Arnoldum Birckman. ———. 1533b. Instrument Buch. Ingolstadt: P. Apianus. Aristotle. 1936. Minor Works. ed. and trans. Walter Stanley Hett. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Ausonio, Ettore. 1968. Theorica speculi concavi sphaerici. In Le Opere di Galileo Galilei,ed. Galileo Galilei, Vol. volume 3. Florence: Speculi Concavi Sphaerici. Bacon, Francis. 1627. The New Atlantis. London: J.H. for William Lee. Bacon, Roger. 1659. Epistola de secretis operibus artis et naturae ed de nullitate magiae. In Frier Bacon his discovery of the miracles of art, nature, and magick. Faithfully translated out of Dr Dees own copy, by T. M. and never before in English. London. Baldi, Bernardino. 1616. Heronis Ctesibii Belopoeeca, hoc est Telifactiva. Augsburg: Davidis Franci. Barlow, William. 1597. The Navigator’s Supply Conteining many things of Principall importance. London: G. Bishop, R. Newberry and R. Barker. © Springer International Publishing AG 2017 183 L.B. Cormack et al. (eds.), Mathematical Practitioners and the Transformation of Natural Knowledge in Early Modern Europe, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 45, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-49430-2 184 Combined Bibliography Beeckman, Isaac. -

The Santissima Annunziata of Florence, Medici Portraits, and the Counter Reformation in Italy

THE SANTISSIMA ANNUNZIATA OF FLORENCE, MEDICI PORTRAITS, AND THE COUNTER REFORMATION IN ITALY by Bernice Ida Maria Iarocci A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Bernice Iarocci 2015 THE SANTISSIMA ANNUNZIATA OF FLORENCE, MEDICI PORTRAITS, AND THE COUNTER REFORMATION IN ITALY Bernice Ida Maria Iarocci Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto 2015 A defining feature of the Counter-Reformation period is the new impetus given to the material expression of devotion to sacred images and relics. There are nonetheless few scholarly studies that look deeply into the shrines of venerated images, as they were renovated or decorated anew during this period. This dissertation investigates an image cult that experienced a particularly rich elaboration during the Counter-Reformation – that of the miracle-working fresco called the Nunziata, located in the Servite church of the Santissima Annunziata in Florence. By the end of the fifteenth century, the Nunziata had become the primary sacred image in the city of Florence and one of the most venerated Marian cults in Italy. My investigation spans around 1580 to 1650, and includes texts related to the sacred fresco, copies made after it, votives, and other additions made within and around its shrine. I address various components of the cult that carry meanings of civic importance; nonetheless, one of its crucial characteristics is that it partook of general agendas belonging to the Counter- Reformation movement. That is, it would be myopic to remain within a strictly local scope when considering this period. -

Bartolomeo Maranta's 'Discourse' on Titian's Annunciation in Naples: Introduction1

Bartolomeo Maranta’s ‘Discourse’ on Titian’s Annunciation in Naples: introduction1 Luba Freedman Figure 1 Titian, The Annunciation, c. 1562. Oil on canvas, 280 x 193.5 cm. Naples: Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte (on temporary loan). Scala/Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali/Art Resource. Overview The ‘Discourse’ on Titian’s Annunciation is the first known text of considerable length whose subject is a painting by a then-living artist.2 The only manuscript of 1 The author must acknowledge with gratitude the several scholars who contributed to this project: Barbara De Marco, Christiane J. Hessler, Peter Humfrey, Francesco S. Minervini, Angela M. Nuovo, Pietro D. Omodeo, Ulrich Pfisterer, Gavriel Shapiro, Graziella Travaglini, Raymond B. Waddington, Kathleen M. Ward and Richard Woodfield. 2 Angelo Borzelli, Bartolommeo Maranta. Difensore del Tiziano, Naples: Gennaro, 1902; Giuseppe Solimene, Un umanista venosino (Bartolomeo Maranta) giudica Tiziano, Naples: Società aspetti letterari, 1952; and Paola Barocchi, ed., Scritti d’arte del Cinquecento, Milan- Naples: Einaudi, 1971, 3 vols, 1:863-900. For the translation click here. Journal of Art Historiography Number 13 December 2015 Luba Freedman Bartolomeo Maranta’s ‘Discourse’ on Titian’s Annunciation in Naples: introduction this text is held in the Biblioteca Nazionale of Naples. The translated title is: ‘A Discourse of Bartolomeo Maranta to the most ill. Sig. Ferrante Carrafa, Marquis of Santo Lucido, on the subject of painting. In which the picture, made by Titian for the chapel of Sig. Cosmo Pinelli, is defended against some opposing comments made by some persons’.3 Maranta wrote the discourse to argue against groundless opinions about Titian’s Annunciation he overheard in the Pinelli chapel.