Olderwiser Lesbians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMERICAN PSYCHO by Mary Harron and Guinevere Turner

AMERICAN PSYCHO by Mary Harron and Guinevere Turner Based on the novel by Bret Easton Ellis Fourth Draft November 1998 INT. PASTELS RESTAURANT- NIGHT An insanely expensive restaurant on the Upper East Side. The decor is a mixture of chi-chi and rustic, with swagged silk curtains, handwritten menus and pale pink tablecloths decorated with arrangements of moss, twigs and hideous exotic flowers. The clientele is young, wealthy and confident, dressed in the height of late-eighties style: pouffy Lacroix dresses, slinky Alaïa, Armani power suits. CLOSE-UP on a WAITER reading out the specials. WAITER With goat cheese profiteroles and I also have an arugula Caesar salad. For entrées tonight I have a swordfish meatloaf with onion marmalade, a rare-roasted partridge breast in raspberry coulis with a sorrel timbale... Huge white porcelain plates descend on very pale pink linen table cloths. Each of the entrees is a rectangle about four inches square and look exactly alike. CLOSE-UP on various diners as we hear fragments of conversation. "Is that Charlie Sheen over there?" "Excuse me? I ordered cactus pear sorbet." WAITER And grilled free-range rabbit with herbed French fries. Our pasta tonight is a squid ravioli in a lemon grass broth... CLOSE-UP on porcelain plates containing elaborate perpendicular desserts descending on another table. PATRICK BATEMAN, TIMOTHY PRICE, CRAIG MCDERMOTT and DAVID VAN PATTEN are at a table set for four. They are all wearing expensively cut suits and suspenders and have slicked-back Script provided for educational purposes. More scripts can be found here: http://www.sellingyourscreenplay.com/library hair. -

CURVE Magazine IBTC.Pdf

A NOT SO ITTY BITTY A gang of lesbian superstars team up for the next big thing: POWER FILM UP’s Itty Bitty Titty Committee. •••••••••• By Candace Moore • Photography by Elisa Shebaro 46 | curve •••••••••• ITTY BITTY By Candace Moore • Photography by Elisa Shebaro From left: Jamie Babbit, Carly Pope and Daniela Sea Jamie is wearing an Alexander McQueen cardigan from Holt Renfrew, and pants by Mandula. Carly is wearing Alexander T I Stylist: Faranak DaCosta Wang, skinny jeans by Paige both from Holt Renfrew, and Makeup artist: Jon Hennessey Miss Sixty ankle boots. Daniela is wearing a Japanese Hair stylist: Shannon Hoover hand-died T-shirt by Mandula, pants and trainers her own. PHOTO CRED September 2007 | 47 that we had at college, were really platforms for lesbians to meet other lesbians and hit on them. That’s where the comedy came into play.” One a.m. descends in an industrial stretch of Southern Guinevere Turner (Go Fish, The L Word) concurs, “I think California on the courtyard of a seedy motel, the type with a there’s a process we have to go through to be extreme in order decades-old neon sign and a Bates Hotel-ish anonymity. The to find out what really matters. I was in ACT UP and Queer weather is uncharacteristically freezing, a cold that goes straight Nation and at that same age was very much in the streets, chant- to the bone. ing ‘We’re here, we’re queer,’ and participating in kiss-ins. The A figure among the trickling-down mist and moths circling things we would do in the name of politics! Like pose naked for the dim lights (is it The L Word’s Daniela Sea?) juggles three T-shirts and all kinds of things. -

Presented by Grand Sponsors

PRESENTED BY GRAND SPONSORS 1 PRESENTING SPONSOR GRAND SPONSORS PREMIERE SPONSORS OFFICIAL SPONSORS SPONSORS ® drink water, not sugar Tickets: 213.480.7065 | outfest.org 2 DAY SPONSORS 15TH ANNIVERSARY FUNDERS PLATINUM SPONSOR OUTFEST FORWARD SPONSORS PROGRAM SPONSORS: FRIENDS OF OUTFEST: MEDIA SPONSORS: Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, LLP Christopher Street West/LA Pride Adelante Magazine Amazon’s One Mississippi Comedian Robbie Rob EuroChannel Inc. Amazon’s Transparent DoubleTree Downtown LA KSPC 88.7 FM The Film Collaborative Goethe Institut Latino Public Broadcasting FotoKem Hollywood Bowl Latino Weekly Review Hulu’s Difficult People International Documentary One More Lesbian Lesbian News Association Light Iron Precinct Bar The Next Family Sharpe Suiting Northern Trust SJ Linking System Project Greenlight WGAW Ramada WeHo Withoutabox SAG-AFTRA SAGIndie Search Party Section II Seed&Spark Sidley Austin LLP SmartSource Sony Pictures Entertainment Symon Productions Outfest 2016 Key Art designed by Alexander Irvine Visit Berlin Outfest 2016 Film Guide designed by Propaganda Creative Group SPONSORS @outfest #outfestla 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome to the 2016 Outfest Los Angeles LGBT ESSENTIALS Film Festival. It’s an election year, and that Film Icon Key 3 means powerful forces are out to separate our Schedule-at-a-Glance 18 community from the rest of the world, and even About Outfest | Major Donors 32 to turn us against each other. Your story, his Tickets | Venues 34 story, her story, their story - it is all our story. Our Film Index by Title 35 collective voice matters. And what better time or place to revel in our own stories — and to discover the commonalities within our own community — than Outfest Los Angeles? Every year, we urge you to explore and GALAS | CENTERPIECES to discover stories that might not, at first, seem Opening Night Gala 4 to be about your own experience. -

Troche, Rose (B

Troche, Rose (b. 1964) Rose Troche. YouTube by Patricia Juliana Smith video still. Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com In the early 1990s, when Rose Troche began her professional filmmaking career with her then-partner Guinevere Turner, invisibility in the arts and media was one of the primary social issues affecting lesbians. Thanks to Go Fish (1994), Troche's first feature film, in which Turner played one of the lead roles, lesbians have become more visible, not as women tortured by their sexuality, as they have traditionally been portrayed, but as individuals for whom female homosexuality is comfortable and, indeed, normal. Rose Troche was born in Chicago in 1964 to Puerto Rican parents, and grew up on the city's north side. While in her teens, she moved with her family to the suburbs, and there, while working part-time in a movie theater, she developed an interest in film. She studied at the University of Illinois, Chicago, where she was an undergraduate major in art history and later a graduate film student. While in film school, she made several short films, including Let's Go Back to My Apartment and Have Sex (1990) and This War Is Not Over (1991). While making her Gabriella series of short films (1991-1993), Troche met Turner, and they began to plot a film based in part on their own experiences and those of their friends in the Chicago lesbian community. In this manner, the lesbian romantic comedy Go Fish, originally titled "Ely and Max," began. -

Repartitie Speciala Intermediara Septembrie 2019 Aferenta Difuzarilor Din Perioada 01.04.2009 - 31.12.2010 DACIN SARA

Repartitie speciala intermediara septembrie 2019 aferenta difuzarilor din perioada 01.04.2009 - 31.12.2010 DACIN SARA TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 11:14 11:14 2003 US/CA Greg Marcks Greg Marcks 11:59 11:59 2005 US Jamin Winans Jamin Winans 007: partea lui de consolare Quantum of Solace 2008 GB/US Marc Forster Neal Purvis - ALCS Robert Wade - ALCS Paul Haggis - ALCS 10 lucruri nu-mi plac la tine 10 Things I Hate About You 1999 US Gil Junger Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith 10 produse sau mai putin 10 Items or Less 2006 US Brad Silberling Brad Silberling 10.5 pe scara Richter I - Cutremurul I 10.5 I 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 10.5 pe scara Richter II - Cutremurul II 10.5 II 2004 US John Lafia Christopher Canaan John Lafia Ronnie Christensen 10.5: Apocalipsa I 10.5: Apocalypse I 2006 US John Lafia John Lafia 10.5: Apocalipsa II 10.5: Apocalypse II 2006 US John Lafia John Lafia 100 de pusti 100 Rifles / 100 de carabine 1969 US Tom Gries Clair Huffaker Tom Gries 100 milioane i.Hr / Jurassic in L.A. 100 Million BC 2008 US Griff Furst Paul Bales EG/FR/ GB/IR/J 11 povesti pentru 11 P/MX/U Alejandro Gonzalez Claude Lelouch - Danis Tanovic - Alejandro Gonzalez Claude Lelouch - Danis Tanovic - Marie-Jose Sanselme septembrie 11'09''01 - September 11 2002 S Inarritu Mira Nair Amos Gitai - SACD SACD SACD/ALCS Ken Loach Sean Penn - ALCS Shohei Imamura Youssef Chahine Samira Makhmalbaf Idrissa Quedraogo Inarritu Amos Gitai - SACD SACD SACD/ALCS Ken -

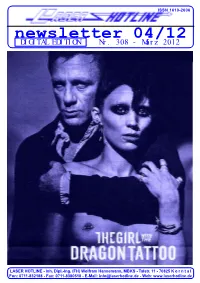

Newsletter 04/12 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 04/12 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 308 - März 2012 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 04/12 (Nr. 308) März 2012 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD- zu hören war. Unser Sound Desi- Designer nicht so schnell aufgibt. Fans, gner hatte daraufhin in unserem Er hatte die Idee, den Film jetzt liebe Filmfreunde! Studio das DCP auf Herz und Nie- vom zweiten installierten Digital- Hatten wir nicht eben erst Ausgabe ren geprüft. Damit sollte sicherge- server abzuspielen. Damit hatten 307 unseres Newsletters publi- stellt werden, dass das DCP (Digi- wir einen durchschlagenden Erfolg: ziert? Unglaublich wie schnell die tal Cinema Package = das digitale endlich wurden die Tiefbässe so Zeit momentan an uns vorbeirast. Pendent zum 35mm-Film) auch wiedergegeben, wie es während As sind gefühlte zwei Newsletter tatsächlich eine LFE-Audio-Spur der Tonmischung klang! Somit hat- pro Woche! Aber das ist vermut- mit den beabsichtigten Sound- ten wir einen passablen Work- lich nur ein Effekt fortschreitenden effekten beinhaltete. Das Ergebnis Around gefunden, mit dem wir un- Alters. Je älter man ist, desto war beruhigend: alle Töne – ob sere Filmpremiere guten Gewis- schneller scheint sich die Erde zu hoch oder tief – waren in der 5.1 sens durchziehen können. Das ge- drehen. Vielleicht aber liegt es PCM Spur enthalten. Damit war fundene Tonproblem im Kino auch nur einfach daran, dass wir eine weitere Dienstreise ins selbst wird aus Zeitgründen erst zu mit Hochdruck an der Fertigstel- Premierenkino fällig. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright THE BEST ELLIS FOR BUSINESS: A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE MASS MEDIA FEMINIST CRITIQUE OF AMERICAN PSYCHO Justine Ettler A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2012 1 DECLARATION I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. -

Sapphic Cinema: an Exploration of Films About Gay Women and Their Relationship to American Society in the Reagan Era and Beyond Melinda Roddy

University of Portland Pilot Scholars History Undergraduate Publications and History Presentations 12-2017 Sapphic Cinema: An Exploration of Films about Gay Women and their Relationship to American Society in the Reagan Era and Beyond Melinda Roddy Follow this and additional works at: https://pilotscholars.up.edu/hst_studpubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, History Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Citation: Pilot Scholars Version (Modified MLA Style) Roddy, Melinda, "Sapphic Cinema: An Exploration of Films about Gay Women and their Relationship to American Society in the Reagan Era and Beyond" (2017). History Undergraduate Publications and Presentations. 6. https://pilotscholars.up.edu/hst_studpubs/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Pilot Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Pilot Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Roddy 1 Sapphic Cinema: An Exploration of Films about Gay Women and their Relationship to American Society in the Reagan Era and Beyond By Melinda Roddy Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History University of Portland December 2017 Roddy 2 Heterosexuality has always been privileged within the United States, which has resulted in, among other things, a lack of representation of LGBTQ+ people film, especially women. Sapphic women and all things Sapphic have largely been marginalized in society. Sapphic, coming from the name of the Greek poet Sappho, means women, or things related to women, who are attracted to other women. -

Outfest #Outfest 5

3 PRESENTING SPONSOR GRAND SPONSORS PREMIERE SPONSORS OFFICIAL SPONSORS S P O N S O R S Tickets: 213.480.7065 or outfest.org 4 DAY SPONSORS AWARD SPONSORS PLATINUM SPONSOR FUNDERS PROGRAM SPONSORS: FRIENDS OF OUTFEST: MEDIA SPONSORS: APA Christopher Street West/LA Pride Blade California Los Angeles Women’s Baseline, LLC The Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf Consulate General & Promotion Theatre Project Consulate General of Brazil Doubletree by Hilton Los Center of the Argentine Republic Make/Shift Magazine Club Skirts Angeles Downtown in Los Angeles MeCam Edwards Wildman The Essential Gay & Lesbian Consulate General of Chile NoMoreDownLow.tv The Film Collaborative Directory Consulate General of the Federal OML Fotokem GoWatchIt.com Republic of Germany Pond5 glee Hollywood Bowl Consulate General of the Rage Monthly Growing Generations Los Angeles Tourism & Netherlands SheWired Hansen, Jacobson, Teller, Hoberman, Convention Board Consulate General of Spain The Bender Newman, Warren, Richman, Rush Macy’s Consulate General of Poland YELP LA & Kaller, LLP Onegoodlove.com in Los Angeles IGLTA SAG-AFTRA dot429.com S Innovative Artists SJ Linking Systems Eurochannel The Lesbian News thedigitalphotobooth.com The Fight Magazine R Los Angeles Film & TV William Morris Endeavor Gay Parent Magazine O Office, French Embassy Entertainment Goethe Institut Paramount Pictures Withoutabox IFP S Pride Travel IMRU Radio N SAGIndie KSPC 88.7 Sony Pictures Entertainment Lesbian.com O Wolfe Video P Outfest 2013 Key Art designed by Alexander Irvine S Outfest 2013 Film Guide designed by Propaganda Creative Group @outfest #outfest 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS ESSENTIALS Schedule-at-a-Glance 20 Parties & Receptions 32 FROM THE EXECUTIVE Membership Information 34 DIRECTOR Community Collaborator Listing 35 Ticketing 37 For more than three decades Outfest has been a leader in Venues 37 LGBT rights and cultural Film Index 38 expression, ensuring that LGBT GALAS stories are created, shared and protected: stories that depict the Opening Night Gala 6 rich diversity of who we are as U.S. -

Rainbowtimesnews.Com FREE! Family Cartoon for Lesbian and the Chez Est: Our Ainbow Imes Gay Parents Featured Biz, Hot in CT! T P

Year 1, Vol. 18 • Dec. 6, 2007 - Jan. 2, 2008 The www.therainbowtimesnews.com FREE! Family cartoon for Lesbian and The Chez Est: Our ainbow imes Gay parents Featured Biz, hot in CT! T p. R p. 8 5 Your LGBT News in Western MA, the Capital District of NY, Northern CT, & Southern VT 8 OUR HOLIDAY OPEN HOUSE PARTY P. 11 P.12 TIPS and POINTERS to SURVIVING the HOLIDAYS P.9 OPRAH and OBAMA? CELEB ENDORSEMENTS P. 8 TRANS MEMBERS of HRC quit! P. 15 LGBT LEADERS COMMIT to HIV/AIDS p. 3 2 • December 6, 2007 - Jan. 2 , 2008 • The Rainbow Times • www.therainbowtimesnews.com Opinions Ann Coulter: Rhetoric with no substance The Controversial Couch Lie back and listen. Then get up and do something By: Nicole C. Lashomb/TRT Editor-in-Chief behalf. Also, according to Coulter, Conservatives By: Suzan Ambrose/TRT Columnist ecently, I was up late channel surf- believe in the defense of the United States, not The holidays. ty, do not feel the warmth of the family fire. ing when I came upon a face well the Liberals because Liberals believe in These words have a way of conjuring up We’re a lot more in sync with the characters known to many—Ann Coulter. R amnesty. I often ponder if those vocal images of going home, being with the ones on the island of misfit toys. There she was in all of her unwarranted, big- Conservatives even know what amnesty is or you love, dreamy Norman Rockwell snap- What happens when Christmas time isn’t all oted glory ranting, as usual, a rhetoric that how it is granted because certainly if they shots of life the way it outta be, Betty Crocker ‘Merry and Bright?’ When having gay appar- was not only difficult to follow based on her understood the concept, they would realize cookies, the singing of carols—and let’s not el isn’t enough? apparent lack of knowledge about the subject that they haven’t a leg to stand on. -

A Study of the Films Purchased for Distribution at the Sundance Film Festival

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects Honors College at WKU Spring 5-16-2014 Will You Buy My Movie? A Study of the Films Purchased for Distribution at the Sundance Film Festival Kaitlynn Smith Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Recommended Citation Smith, Kaitlynn, "Will You Buy My Movie? A Study of the Films Purchased for Distribution at the Sundance Film Festival" (2014). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 481. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/481 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILL YOU BUY MY MOVIE? A STUDY OF THE FILMS PURCHASED FOR DISTRIBUTION AT THE SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL A Capstone Experience/Thesis Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts with Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Kaitlynn H. Smith ***** Western Kentucky University 2014 CE/T Committee: Approved by Dr. Ted Hovet, Advisor Dr. Dawn Hall ____________________ Advisor Lisa Draskovich-Long Department of English Copyright by Kaitlynn H. Smith 2014 ABSTRACT Robert Redford created the Sundance Institute with the intention of helping filmmakers outside of the Hollywood system hone their craft with assistance from established industry professionals. Today, the Sundance Film Festival, held every year in January, provides an opportunity for independent filmmakers to sell their films to distribution companies and get their name out to executives in Hollywood. -

The Lesbian Perception: Representation in Anonymous Questionnaires

IMPACT: Journal of Modern Developments in Arts and Linguistic Literature (IMPACT: JMDALL) Vol. 1, Issue 2, Dec 2017, 7-12 © Impact Journals THE LESBIAN PERCEPTION: REPRESENTATION IN ANONYMOUS QUESTIONNAIRES MAYA SCHWARTZ LAUFER Research Scholar, Babes Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania ABSTRACT This article is a small portion of my Ph.D. thesis; it shows the process and conclusion of integration of Lesbian characters in a western context in the media from an anonymous international questionaries’ point of view addressed to the Lesbian community. My research compared different Lesbian oriented films, television shows and Internet based (web) series from the early 1930's to today; the Butch & Femme categorization, the shattering of the Lesbian masculine image throughout media history and the need to become mainstream opposed to queer, and simply blend into the majority of the population. I have explored it with numerous films, television shows and Internet based series (web series) – in order to show the progress. In addition, I have administered anonymous questionnaires, conducted a small sample focus group with Lesbians ages 16 to 45, in order to understand how the modern Lesbian portrays herself and believe the media represents her. I have explored various films and television shows from the different eras, based my research on different books, articles and studies of a similar nature, starting with Queer theory, and post-feminist theory; based on Foucault (1978), Butler (1990), Kama (2003) and Beauvoir (1949) The need to “Belong” is every minority - group’s aspiration, especially in young women, the desire to “look up to someone, or imitate them” or identify with them; or how “deification” according to: Lemish, D.