Report Resumes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneath the Surface *Animals and Their Digs Conversation Group

FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS August 2013 • Northport-East Northport Public Library • August 2013 Northport Arts Coalition Northport High School Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Courtyard Concert EMERGENCY Volunteer Fair presents Jazz for a Yearbooks Wanted GALLERY EXHIBIT 1 Registration begins for 2 3 Friday, September 27 Children’s Programs The Library has an archive of yearbooks available Northport Gallery: from August 12-24 Summer Evening 4:00-7:00 p.m. Friday Movies for Adults Hurricane Preparedness for viewing. There are a few years that are not represent- *Teen Book Swap Volunteers *Kaplan SAT/ACT Combo Test (N) Wednesday, August 14, 7:00 p.m. Northport Library “Automobiles in Water” by George Ellis Registration begins for Health ed and some books have been damaged over the years. (EN) 10:45 am (N) 9:30 am The Northport Arts Coalition, and Safety Northport artist George Ellis specializes Insurance Counseling on 8/13 Have you wanted to share your time If you have a NHS yearbook that you would like to 42 Admission in cooperation with the Library, is in watercolor paintings of classic cars with an Look for the Library table Book Swap (EN) 11 am (EN) Thursday, August 15, 7:00 p.m. and talents as a volunteer but don’t know where donate to the Library, where it will be held in posterity, (EN) Friday, August 2, 1:30 p.m. (EN) Friday, August 16, 1:30 p.m. Shake, Rattle, and Read Saturday Afternoon proud to present its 11th Annual Jazz for emphasis on sports cars of the 1950s and 1960s, In conjunction with the Suffolk County Office of to start? Visit the Library’s Volunteer Fair and speak our Reference Department would love to hear from you. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Theenvironmental Sustainabilityissue

SUMMER 2021 ISSUE 58 Evin Senin Dünyan RC QUARTERLY SUMMER 2021 ISSUE 58 Dünya Senin Evin Dünyanın sanat ve tasarımla daha iyi bir yer olacağına inanıyor; sürdürülebilir bir dünya için var gücümüzle çalışıyoruz. the environmental KTSM, Kale Grubu tarafından desteklenen, disiplinlerarası paylaşımlara imkan veren üretim ve buluşma noktasıdır. Kale Tasarım ve Sanat Merkezi sustainability issue kaletasarimsanatmerkezi.org / kaletasarimvesanatmerkezi / ktsm_org tepta_robertcollege_ilan_haziran2021_195x260mm_2.pdf 1 03/06/21 10:07 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K The cover for this issue SUMMER 2021 ISSUE 58 celebrates the vast biodiversity of our campus. All photos were taken on RC grounds by faculty and students, as part of an effort to catalog the Alumni Journal published periodically by flora and fauna found the RC Institutional Advancement Office for at RC. approximately 10,000 members of the RC the environmental community: graduates, students, faculty, sustainability issue administration, parents and friends. The trees, flowers, birds, koi fish, Bosphorus beetle, and new beehives of the RC campus all bestow on the RC community a deep appreciation of and respect for nature. In this issue we delve into environmental sustainability, an urgent matter for humanity and now a strategic focus for RC. The RCQ chronicles the latest developments at school and traces the school’s history for the seeds that were sown for today. Many RC alumni are active as leaders, teachers, activists, and professionals in environmental sustainability-related areas. There is much news and In inspiration to share from them as well. this The pandemic did not slow down the RC community: RC students continue to display many accomplishments, and RC alumni have published books and received issue prestigious awards. -

A.U.I. Trustee Scholarships Are Established

VOLUME 18, NUMBER 13 Published by the BNL Personnel Office JANUARY 20, 1965 BERA FILM SERIES PURPLE NOON A.U.I. TRUSTEE SCHOLARSHIPS ARE ESTABLISHED A scholarship program for the children of regular employees of Brookhaven National Laboratory and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory has been established by the Board of Trustees of Associated Universities, Inc. Dr. Maurice Goldhaber, Director, announced the creation of the A.U.I. Trustee Scholarships to all Brookhaven employees on January 18. Under the new program, up to ten scholarships each year will be made avail- able to the children of regular BNL employees. They will carry a stipend of up to $900 per year. For those who maintoin satisfactory progress in school, the scholor- ships will be renewoble for up to three additional years. Winners of the awards may attend any accredited college or university in the United States and may select any course of study leading to a bachelor’s degree. Thurs., Jan. 21 - lecture Hall - 8:30 p.m. The scholarships will be granted on o strictly competitive basis, independent Rene Clement (“Forbidden Games,” of financial need and the existence of other forms of aid to the student. Winners “Gervaise”) has here fashioned a highly will be selected on the basis of their secondary school academic records and gen- entertaining murder thriller, beautifully eral aptitude for college work as indicated by achievement and aptitude tests. photographed in color by Henri Decae The Laboratory will not be involved in the processing of applications or the (“400 Blows, ” “The Cousins,” “Sundays determination of scholarship winners. -

Mobility of Secondary School Pupils and Recognition of Study Periods Spent Abroad

Mobility of Secondary School Pupils and Recognition of Study Periods Spent Abroad A Survey edited by Roberto Ruffino Conference Proceedings edited by Elisabeth Hardt A project supported by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Education and Culture the federation of organisations in Europe The survey was co-ordinated by Roberto Ruffino with the assistance of Kris Mathay. The survey would not have been possible without the assistance of 20 Member Organisations of the European Federation for Intercultural Learning who co-ordinated and conducted the survey at national level. Their contribution, as well as the financial support of the European Commission in the realisation of this survey is hereby thankfully acknowledged. European Federation for Intercultural Learning (EFIL) Avenue Emile Max, 150, 1030 Brussels Tel: +32-2.514.52.50, Fax: +32-2.514.29.29 http://efil.afs.org the federation of organisations in Europe 3 I Table of Contents I Table of contents 4 4 Mobility Schemes – Sending 21 4.1 Schools 21 II Mobility Survey 7 4.1.1 Legislation 21 4.1.2 Mobility References in the Curriculum 22 1 Some Introductory Notes 4.1.3 Internationalisation on Educational Mobility of European for Secondary Secondary Schools 22 School Pupils 8 4.2 Public Agencies 23 1.1 Educational Mobility and the EU 9 1.1.1 The Socrates Programme 9 5 Quality and Recognition 1.1.2 Tackling Obstacles Issues 24 to Mobility 10 5.1 Quality 24 1.2 Long-Term Individual Mobility for Upper-Secondary 5.2 Recognition 25 School Pupils 12 1.2.1 Maximising the Intercultural Awareness of Active 6 Good Practices 30 European Citizens 12 1.2.2 The Case of AFS 6.1 On Legislation Regarding Intercultural Accreditation 30 Programs, Inc. -

Sensesational Storytime Manual

SENSESATIONAL STORYTIME MANUAL A handbook containing storytime planning cards including songs, rhymes, group activities, sensory exploration, and crafts appropriate for children with sensory/special needs. SENSORY STORYTIME MANUAL AUTHORS Carolyn Brooks Branch Manager, El Dorado Hills Library Debbie Arenas Early Childhood Literacy Specialist, El Dorado Hills Library Geneva Paulson Early Childhood Literacy Specialist, Placerville Library Robyn Chu MOT, OTR/L Growing Healthy Children Therapy Services TYPING & LAYOUT Kathryn McGinness El Dorado County Library SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to acknowledge and thank Betsy Diamant-Cohen and her storytime program, Mother Goose on the Loose, for inspiring us to provide excellent service to the youngest members of our community. A tremendous thank you to Kathi Guerrero and First 5 of El Dorado for all of their support for our community’s children. PRINTING Copyright© 2014 by the El Dorado County Library. Permission is granted to print and reproduce the contents of this manual for personal, educational, and non-commercial use. This project was funded, in part or whole, by a federal IMLS grant, administered by the California State Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA). ii To the families of El Dorado County who read to their children each and every day TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by Carolyn Brooks…………………........................…...5 Chapter 1: Background & Research Introduction.............................................................................................7 What is Sensory -

34 Writers Head to 7Th Annual Johnny Mercer Foundation Writers Colony at Goodspeed Musicals

NEWS RELEASE FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: Elisa Hale at (860) 873-8664, ext. 323 [email protected] Dan McMahon at (860) 873-8664, ext. 324 [email protected] 34 Writers Head to 7th Annual Johnny Mercer Foundation Writers Colony at Goodspeed Musicals – 21 Brand New Musicals will be part of this exclusive month-long retreat – This year’s participants boast credits as diverse as: Songwriters of India Aire’s “High Above” (T. Rosser, C. Sohne) Music Director for NY branch of Playing For Change (O. Matias) Composer for PBS (M. Medeiros) Author of Muppets Meet the Classic series (E. F. Jackson) Founder of RANGE a capella (R. Baum) Lyricist for Cirque du Soleil’s Paramour (J. Stafford) Member of the Board of Directors for The Lilly Awards Foundation and Founding Director of MAESTRA (G. Stitt) Celebrated Recording Artists MIGHTY KATE (K. Pfaffl) Teaching artist working with NYC Public Charter schools and the Rose M. Singer Center on Riker’s Island (I. Fields Stewart) Broadway Music Director/Arranger for If/Then, American Idiot, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee and others (C. Dean) EAST HADDAM, CONN.,JANUARY 8 , 2019: In what has become an annual ritual, a total of 34 established and emerging composers, lyricists, and librettists will converge on the Goodspeed campus from mid-January through mid-February 2019 to participate in the Johnny Mercer Foundation Writers Colony at Goodspeed Musicals. The writing teams, representing 21 new musicals, will populate the campus, creating a truly exciting environment for discovery and inspiration. The Johnny Mercer Writers Colony at Goodspeed is an unparalleled, long-term residency program devoted exclusively to musical theatre writing. -

The Socio-Spatial Transformation of Beyazit Square

THE SOCİO-SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION OF BEYAZIT SQUARE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES OF İSTANBUL ŞEHİR UNIVERSITY BY BÜŞRA PARÇA KÜÇÜKGÖZ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN SOCIOLOGY FEBRUARY 2018 ABSTRACT THE SOCIO-SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION OF BEYAZIT SQUARE Küçükgöz Parça, Büşra. MA in Sociology Thesis Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Eda Ünlü Yücesoy February 2018, 136 Pages In this study, I elaborated formation and transformation of the Beyazıt Square witnessed in modernization process of Turkey. Throughout the research, I examine thematically the impacts of socio-political breaks the on shaping of Beyazıt Square since the 19th century. According to Lefebvre's theory of the spatial triad, which is conceptualized as perceived space, conceived space and lived space, I focus on how Beyazıt Square is imagined and reproduced and how it corresponds to unclear everyday life. I also discuss the creation of ideal public space and society as connected with the arrangement of Beyazit Square. In this thesis, I tried to discuss the Beyazıt Square which has a significant place in social history in the light of an image of “ideal public space or square". Keywords: Beyazıt Square, Public Space, Conceived Space, Lived Space, Lefebvre, Production of Space. iv ÖZ BEYAZIT MEYDANI’NIN SOSYO-MEKANSAL DÖNÜŞÜMÜ Küçükgöz Parça, Büşra. Sosyoloji Yüksek Lisans Programı Tez Danışmanı: Doç. Dr. Eda Ünlü Yücesoy Şubat 2018, 136 Sayfa Bu çalışmada, Türkiye'nin modernleşme sürecine tanıklık eden Beyazıt Meydanı'nın oluşum ve dönüşümünü araştırdım. Araştırma boyunca özellikle sosyo-politik kırılmaların Beyazıt Meydanı'nın şekillenmesinde ne tür etkiler yarattığını 19. -

Raising Children with Roots, Rights & Responsibilities

Raising Children With Roots, Rights & Responsibilities: Celebrating the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child Written by Lori DuPont, Joanne Foley, and Annette Gagliardi Founders of the Circle for the Child Project Edited and designed by Julie Penshorn, Co-Director, Growing Communities for Peace Published by University of Minnesota Human Rights Resource Center and the Stanley Foundation Copyright © 1999 Human Rights Resource Center, University of Minnesota The Human Rights Education Series is published by the Human Rights Resource Center at the University of Minnesota and the Stanley Foundation. The series provides resources for the ever-growing body of educators and activists working to build a culture of human rights in the United States and throughout the world. Raising Children with Roots, Rights, & Responsibilities: Celebrating the Convention on the Rights of the Child may be reproduced without permission for educational use only. No reproductions may be sold for profit. Excerpted or adapted material from this publication must include full citation of the source. To reproduce for any other purposes, a written request must be submitted to the Human Rights Resource Center. The Human Rights Education Series is edited by Nancy Flowers. Edited and designed by Julie Penshorn, Co-Director of Growing Communities for Peace. Illustrations by eleven-year-old Margaret Anne Gagliardi. Cover design donated by Nancy Hope. ISBN 0-9675334-1-3 To order further copies of Raising Children With Roots, Rights, & Responsibilities: Celebrating the Conven- tion on the Rights of the Child, contact: Human Rights Resource Center University of Minnesota 229 - 19th Avenue South, Room 439 Minneapolis, MN 55455 Tel: 1-888-HREDUC8 Fax: 612-625-2011 email: [email protected] http://www.hrusa.org and http://www.umn.edu/humanrts A contribution to the United Nations Decade for Human Rights Education, 1995-2004 Dedication This book is lovingly dedicated to our children: Jesse, Jacob, Rachel, Erica, Marian, Maggie, and Maria and to the children of the world. -

Dealing with Death

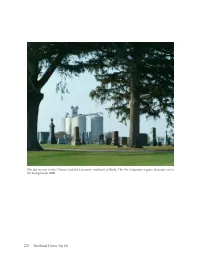

The old section of the Clinton-Garfield Cemetery southeast of Rolfe. The Pro Cooperative grain elevators are in the background. 2000. 270 The Road I Grew Up On DEALING WITH DEATH A Day of Mourning Don Grant died on September 29, 2001. I had visited him on Thursday, September 13, two days after the World Trade Center and Pentagon were attacked on September 11. Then on the national day of mourning on Friday, September 14, I wrote an essay in response to the events of the week. It included the following portion that begins with reference to a photo excursion I had taken with a friend, Janis Pyle. She wanted me to bring my camera and help her document farms and other places of her rural heritage in central Iowa. It was on that outing that I saw Don for the last time. Janis and I talked about the attacks on New York and Washington and how people would be quick to retaliate rather than understand that the best form of national defense is to share power and resources more equitably in the world. Janis and I also talked at length about rural and small-town life and how the agricultural economy is in really bad shape. It is hard for some people to realize how bad things are because the tragedy of the farm scene doesn’t have the kind of visual impact for television as airliners hitting the Twin Towers and the subsequent collapse of those icons of American prosperity. The farms we visited were like so many around the Rolfe area, vastly different than when they thrived with activity in past decades. -

Western Movie Trivia Questions

WESTERN MOVIE TRIVIA QUESTIONS ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Who plays the sheriff in Unforgiven (1992)? 2> Who is the director and producer of Appaloosa (2008)? 3> Which Native American tribe attacked the village, defended by Dunbar (Dances with Wolves)? 4> Who is Shane from a 1953 movie of the same name? 5> Who really shot Liberty Valance (The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance)? 6> Which tribe adopted Jack Crab, played by Dustin Hoffman (Little Big Man)? 7> Jeff Bridges portrayed famous character of the Dude in Big Lebowski. Which of the following westerns also featured a character named Dude? 8> The Magnificent Seven is a western remake of which famous movie? 9> Owen Thursday is a graduate of which military school (Fort Apache)? 10> What does the name Manco mean (For a Few Dollars More)? 11> Who plays Seth Bullock in TV series Deadwood? 12> John Wayne won an Oscar for his role in which movie? 13> What is Ringo's first name (The Gunfighter)? 14> The action takes place in Rio Arriba in... 15> What is the US title for a Sergio Leone film Duck, You Sucker! ? Answers: 1> Gene Hackman - A memorable quote is 'It's a hell of a thing killin' a man. You take away all he's got and all he's ever gonna have.' 2> Ed Harris - Alan Miller directed a film called The Appaloosa in 1966, starring Marlon Brando. 3> Pawnee - Some of the Pawnee people practiced child sacrifice. 4> A gunslinger - The last living member of the cast, Jack Palance, died in 2006. -

July 1978 Scv^ Monthly for the Press && the Museum of Modern Art Frl 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y

d^c July 1978 ScV^ Monthly for the Press && The Museum of Modern Art frl 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Department of Public Information, (212)956-2648 What' s New Page 1 What's Coming Up Page 2 Current Exhibitions Page 3-4 Gallery Talks, Special Events Page 4-5 Ongoing Page Museum Hours, Admission Fees Page 6 Events for Children , Page 6 WHAT'S NEW DRAWINGS Artists and Writers Jul 10—Sep 24 An exhibition of 75 drawings from the Museum Collection ranging in date from 1889 to 1976. These drawings are portraits of 20th- century American and European painters and sculptors, poets and philosophers, novelists and critics. Portraits of writers in clude those of John Ashbery, Joe Bousquet, Bertolt Brecht, John Dewey, Iwan Goll, Max Jacob, James Joyce, Frank O'Hara, Kenneth Koch, Katherine Anne Porter, Albert Schweitzer, Gertrude Stein, Tristan Tzara, and Glenway Wescott. Among the artists represent ed by self-portraits are Botero, Chagall, Duchamp, Hartley, Kirchner, Laurencin, Matisse, Orozco, Samaras, Shahn, Sheeler, and Spilliaert. Directed by William S. Lieberman, Director, De partment of Drawings. (Sachs Galleries, 3rd floor) VARIETY OF MEDIA Selections from the Art Lending Service Jul 10—Sep 5 An exhibition/sale of works in a variety of media. (Penthouse, 6th floor) PHOTOGRAPHY Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since 1960 Jul 28—Oct 2 This exhibition of approximately 200 prints attempts to provide a critical overview of the new American photography of the past Press Preview two decades. The central thesis of the exhibition claims that Jul 26 the basic dichotomy in contemporary photography distinguishes llam-4pm those who think of photography fundamentally as a means of self- expnession from those who think of it as a method of exploration.