A Guide to Best Practice for Watching Marine Wildlife a Guide to Best Practice for Watching Marine Wildlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Assessment/Assessment of Effect ___

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Cape Hatteras National Seashore Environmental Assessment/Assessment of Effect ___ Review and Adjustment of Wildlife Protection Buffers April 2015 1 Department of the Interior National Park Service Environmental Assessment: Review and Adjustment of Wildlife Protection Buffers Cape Hatteras National Seashore North Carolina April 2015 Summary The National Park Service (NPS) proposes to modify wildlife protection buffers established under the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Final Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement of 2010 (ORV FEIS). This proposed action results from a review of the buffers, as mandated by Section 3057 of the Defense Authorization Act of Fiscal Year 2015, Public Law 113-291 (2014 Act). The 2014 Act directs the NPS “to ensure that the buffers are of the shortest duration and cover the smallest area necessary to protect a species, as determined in accordance with peer-reviewed scientific data.” This environmental assessment (EA) deals solely with review and modification, as appropriate, of wildlife protection buffers and the designation of pedestrian and vehicle corridors around buffers. All other aspects of the ORV FEIS remain unchanged. This EA analyzes potential impacts to the human environment resulting from two alternative courses of action. These alternatives are: alternative A (no action, i.e., continue current management under the ORV FEIS), and alternative B (modify buffers and provide additional access corridors) (the NPS preferred alternative). As more fully described in the EA, the proposed modifications to buffers and corridors in alternative B are as follows: For American oystercatcher: There would be an ORV corridor at the waterline during nesting, but only when (a) no alternate route is available, and (b) the nest is at least 25 meters from the vehicle corridor. -

Modelling Radiation Exposure and Radionuclide Transfer for Non-Human Species

Modelling Radiation Exposure and Radionuclide Transfer for Non-human Species Report of the Biota Working Group of EMRAS Theme 3 Environmental Modelling for RAdiation Safety (EMRAS) Programme FOREWORD Environmental assessment models are used for evaluating the radiological impact of actual and potential releases of radionuclides to the environment. They are essential tools for use in the regulatory control of routine discharges to the environment and also in planning measures to be taken in the event of accidental releases; they are also used for predicting the impact of releases which may occur far into the future, for example, from underground radioactive waste repositories. It is important to check, to the extent possible, the reliability of the predictions of such models by comparison with measured values in the environment or by comparing with the predictions of other models. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has been organizing programmes of international model testing since the 1980s. The programmes have contributed to a general improvement in models, in transfer data and in the capabilities of modellers in Member States. The documents published by the IAEA on this subject in the last two decades demonstrate the comprehensive nature of the programmes and record the associated advances which have been made. From 2003 to 2007, the IAEA organised a programme titled “Environmental Modelling for RAdiation Safety” (EMRAS). The programme comprised three themes: Theme 1: Radioactive Release Assessment ⎯ Working Group 1: Revision of IAEA Technical Report Series No. 364 “Handbook of parameter values for the prediction of radionuclide transfer in temperate environments (TRS-364) working group; ⎯ Working Group 2: Modelling of tritium and carbon-14 transfer to biota and man working group; ⎯ Working Group 3: the Chernobyl I-131 release: model validation and assessment of the countermeasure effectiveness working group; ⎯ Working Group 4: Model validation for radionuclide transport in the aquatic system “Watershed-River” and in estuaries working group. -

Emission Station List by County for the Web

Emission Station List By County for the Web Run Date: June 20, 2018 Run Time: 7:24:12 AM Type of test performed OIS County Station Status Station Name Station Address Phone Number Number OBD Tailpipe Visual Dynamometer ADAMS Active 194 Imports Inc B067 680 HANOVER PIKE , LITTLESTOWN PA 17340 717-359-7752 X ADAMS Active Bankerts Auto Service L311 3001 HANOVER PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-632-8464 X ADAMS Active Bankert'S Garage DB27 168 FERN DRIVE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-0420 X ADAMS Active Bell'S Auto Repair Llc DN71 2825 CARLISLE PIKE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-4752 X ADAMS Active Biglerville Tire & Auto 5260 301 E YORK ST , BIGLERVILLE PA 17307 -- ADAMS Active Chohany Auto Repr. Sales & Svc EJ73 2782 CARLISLE PIKE , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-479-5589 X 1489 CRANBERRY RD. , YORK SPRINGS PA ADAMS Active Clines Auto Worx Llc EQ02 717-321-4929 X 17372 611 MAIN STREET REAR , MCSHERRYSTOWN ADAMS Active Dodd'S Garage K149 717-637-1072 X PA 17344 ADAMS Active Gene Latta Ford Inc A809 1565 CARLISLE PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-633-1999 X ADAMS Active Greg'S Auto And Truck Repair X994 1935 E BERLIN ROAD , NEW OXFORD PA 17350 717-624-2926 X ADAMS Active Hanover Nissan EG08 75 W EISENHOWER DR , HANOVER PA 17331 717-637-1121 X ADAMS Active Hanover Toyota X536 RT 94-1830 CARLISLE PK , HANOVER PA 17331 717-633-1818 X ADAMS Active Lawrence Motors Inc N318 1726 CARLISLE PIKE , HANOVER PA 17331 717-637-6664 X 630 HOOVER SCHOOL RD , EAST BERLIN PA ADAMS Active Leas Garage 6722 717-259-0311 X 17316-9571 586 W KING STREET , ABBOTTSTOWN PA ADAMS Active -

Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants from Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1934 Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants From Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish. Anna Theresa Daigle Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Daigle, Anna Theresa, "Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants From Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish." (1934). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8182. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8182 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOLKLORE AND ETYMOLOGICAL GLOSSARY OF THE VARIANTS FROM STANDARD FRENCH XK JEFFERSON DAVIS PARISH A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF SHE LOUISIANA STATS UNIVERSITY AND AGRICULTURAL AND MECHANICAL COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES BY ANNA THERESA DAIGLE LAFAYETTE LOUISIANA AUGUST, 1984 UMI Number: EP69917 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dissertation Publishing UMI EP69917 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). -

Seashore Pocket Guide

. y a B e e L d n a n i t r a M e b m o C , h t u o m n y L ) e v o b a ( . e m i t m e h t e v i g u o y f i e c i v e r c n e d d i h a m o r f t u o . a n i l l a r o c d n a e s l u d s a h c u s s d e e w a e s b a r C e l b i d E k u . v o g . k r a p l a n o i t a n - r o o m x e . w w w e r a t s a o c s ’ r o o m x E n o e f i l d l i w e r o h s a e s k c a b e v o m n e t f o l l i w s b a r c d n a h s i F . l l i t s y r e v g n i p e e k d e r r e v o c s i d n a c u o y s l o o p k c o r r o f k o o l o t s e c a l p e t i r u o v a f r u o f o e m o S , g n i h c t a w e m i t d n e p S . -

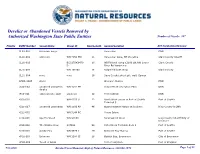

Derelict Or Abandoned Vessels Removed by Authorized Washington State Public Entities

Derelict or Abandoned Vessels Removed by 514 Authorized Washington State Public Entities Priority DVRP # Vessel_Name Vessel ID Length (ft) General Location Removed By CL10-002 unknown WN 7354 MD 31 Vancouver Lake, NE shoreline Clark County Sheriff CL10-003 BCC17543M79D 16 WDFW boat ramp 12100 blk NW Lower River Rd Vanc Clark County CL10-004 WN 106 GA 16 Ridgefield boat ramp Clark County CL11-004 none none 16 Davy Crocket sheet pile wall, Camus IS12-002 unnamed Livingston dingh WN 4154 MF Anacortes at Deception Pass DNR y JF10-011 unknown blue skiff unknown 12 Port Hadlock DNR KI08-010 WN 6250 V 22 North West corner of Port of Seattle Terminal 5 Port of Seattle KI10-017 unnamed catamaran WN 1983 NP 46 Quartermaster Harbor at Dockton King County & DNR KI11-005 WN 5148 RC Maury Island KI12-006 Sport'n Wood WN 9566X Sammamish River King County Sheriff/City of KP07-019 Balboa WN 1949 KH 16 Manzanita Bay, Bainbridge Island City of Bainbridge Island KP10-026 WN 8174 R 22 Eagle Harbor, Bainbridge Island COBI/DNR KP10-027 WN 1481 JA 27 Eagle Harbor, Bainbridge Island COBI/DNR KP11-003 Willetta WN 7048 JA 38 Port of Poulsbo Marina Port of Poulsbo KP11-004 unknown sunken v 0 Eagle Harbor City of Bainbridge Island KP12-011 Altair CCY242000676 Liberty Bay DNR (Jobs Now) KP12-012 Vision 250177 Liberty Bay DNR (Jobs Now) KP12-013 Chris-E WN-0089KD 33 Liberty Bay DNR (Jobs Now) KP12-014 WN-4648JC Liberty Bay DNR (Jobs Now) KP12-018 Miss Serene WN 308 SUN Sinclair inlet near SW Bay St., ort Orchard Port Orchard PD Tuesday, January 07, 2014 Derelict Vessel Removal Program, Dept. -

Seashore Wildlife and Tides Education and Learning Pack

Seashore Wildlife and Tides Education and Learning Pack 0 Key Terms Seashore Wildlife Tides East Beach West Beach Shingle Sand Dunes Marram Grass Site of Special Scientific Interest Maritime and Coastal Agency Learning Objectives To compare the differences between East Beach and West Beach To understand which animals live on the Beaches To understand why West Beach is a Local Nature Reserve To understand why we have to respect the tide To compare different habitats, and what we find in each of them. 1 Seashore and Wildlife Littlehampton is lucky enough to have two different beaches, East and West Beach. Pebbles dominate the landscape when the tide is in but a large se bed, called ‘Winkle Island’, is exposed at low tide, along with long sand flats. Groynes on both beaches help the flow of the sea to try to detract the longshore drift from creating too much sand at the river mouth. The beaches are award-winning, with East Beach being awarded the 2015 Blue Flag and Seaside Award. East Beach East Beach is a lot busier in the holidays with tourists from all over the country visiting the seaside on day trips. East beach is mainly for tourists with cafes, adventure golf courses and train rides along the promenade operate in the summer months. East Beach is also home to the East Beach Cafe, designed by Heatherwick Studios. Britain’s longest bench can also be found along East Beach Promenade. It runs for 324 metres along the seafront and is made East Beach and Cafe, Littlehampton from reclaimed tropical hardwood slats from coastal groynes and landfill. -

Sustainable Development, Poaching, and Illegal Wildlife Trade in India

Sustainable Development, Poaching, and Illegal Wildlife Trade in India Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Niraj, Shekhar Kumar Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 14:52:36 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194196 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT, POACHING, AND ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE IN INDIA by Shekhar Kumar Niraj ________________________ Copyright © Shekhar Kumar Niraj 2009 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF NATURAL RESOURCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN RENEWABLE NATURAL RESOURCES STUDIES In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2009 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Shekhar Kumar Niraj entitled Sustainable Development, Poaching, and Illegal Wildlife Trade in India and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________________ Date: 01/30/2009 Paul R. Krausman ___________________________________________________________________ Date: 01/30/2009 William W. Shaw ____________________________________________________________________ Date: 01/30/2009 Randy R. Gimblett ____________________________________________________________________ Date: 01/30/2009 John L. Koprowski Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

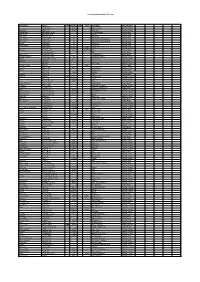

Report Document

Derelict or Abandoned Vessels Removed by Authorized Washington State Public Entities Number of Vessels: 867 Priority DVRP Number Vessel Name Vessel ID Boat Length General Location APE Conducting Removal CL03-001 Unknown barge Vancouver DNR CL10-002 unknown WN 7354 MD 31 Vancouver Lake, NE shoreline Clark County Sheriff CL10-003 BCC17543M79 16 WDFW boat ramp 12100 blk NW Lower Clark County D River Rd Vancouver CL10-004 WN 106 GA 16 Ridgefield boat ramp Clark County CL11-004 none none 16 Davy Crocket sheet pile wall, Camus GH03-002B Arctic Westport Marina DNR IS12-002 unnamed Livingston WN 4154 MF Anacortes at Deception Pass DNR dinghy JF10-011 unknown blue skiff unknown 12 Port Hadlock DNR KI08-010 WN 6250 V 22 North West corner of Port of Seattle Port of Seattle Terminal 5 KI10-017 unnamed catamaran WN 1983 NP 46 Quartermaster Harbor at Dockton King County & DNR KI11-005 WN 5148 RC Maury Island KI12-006 Sport'n Wood WN 9566X Sammamish River King County Sheriff/City of Kenmore KI15-016 The Wazzu Crew 297584 54 Fishermens Terminal dock 8 Port of Seattle KI15-020 Adulis-Zula WN 9979 J 29 Shilshole Bay Marina Port of Seattle KP03-004 Unknown WN 1584 JE 26 Ostrich Bay, Bremerton City of Bremerton KP03-008 Touch of Glass Port of Kingston Port of Kingston 7/31/2019 Derelict Vessel Removal, Dept of Natural Resouces, 360-902-1574 Page 1 of 42 Priority DVRP Number Vessel Name Vessel ID Boat Length General Location APE Conducting Removal KP03-011A Petunia Eagle Harbor City of Bainbridge Island KP03-011B Unknown2 Eagle Harbor City of Bainbridge Island -

Report on San Miguel Island of the Channel Islands, California

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE rtr LIBRARY '"'' Denver, Colorado D-1 s~ IJ UNITED STATES . IL DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE I ' I I. i? ~~ REPORT ON 1 ·•*·;* SAN MIGUEL ISLAND ii' ' ·OF THE CHANNEL ISLANDS .. CALIFORNIA I. November 1, 1957 I " I ' I~ 1· Prepared By I Region Four, National Park Service Division of Recreation. Resource Planning I GPO 975965 I CONTENTS SUMMARY SECTION 1 ---~------------------------ CONCLUSIONS - ------------------------------- z ESTIMATED COSTS --------------------------- 3 REPORT -----------------------"-------------- 5 -I Authorization and Purpose __ .;, ______________ _ 5 Investigation Activities --------------------- 5 ,, 5 Population ---'-- ~------- - ------------------ Accessibility ----------------- ---- - - - ----- 6 Background Information -------------------- 7 I Major Characteristics --------------------- 7 Scenic Features --------------------- 7 Historic or prehistoric features -------- 8 I Geological features- - ------ --- ------- -- lZ .Biological features------------'-•------- lZ Interpretive possibilities-------------- 15 -, Other recreation possibilities -"'.-------- 16 NEED FOR CONSERVATION 16 ;' I BOUNDARIES AND ACREAGE 17 1 POSSIBLE DEVELOPMENT ---------------------- 17 PRACTICABILITY OF ADMINISTRATION, I OPERATION, PROTECTION AND PUBLIC USE--- 17 OTHER LAND RESOURCES OR USES -------------- 18 :.1 LAND OWNERSHIP OR STATUS------------------- 19 ·1 LOCAL ATTITUDE -----------------------•------ 19 PROBABLE AVAILABILITY----------------------- 19 'I PERSONS INTERESTED-------------------------- -

Geology at Point Reyes National Seashore and Vicinity, California: a Guide to San Andreas Fault Zone and the Point Reyes Peninsula

Geology at Point Reyes National Seashore and Vicinity, California: A Guide to San Andreas Fault Zone and the Point Reyes Peninsula Trip highlights: San Andreas Fault, San Gregorio Fault, Point Reyes, Olema Valley, Tomales Bay, Bolinas Lagoon, Drakes Bay, Salinian granitic rocks, Franciscan Complex, Tertiary sedimentary rocks, headlands, sea cliffs, beaches, coastal dunes, Kehoe Beach, Duxbury Reef, coastal prairie and maritime scrublands Point Reyes National Seashore is an ideal destination for field trips to examine the geology and natural history of the San Andreas Fault Zone and the North Coast of California. The San Andreas Fault Zone crosses the Point Reyes Peninsula between Bolinas Lagoon in the south and Tomales Bay in the north. The map below shows 13 selected field trip destinations where the bedrock, geologic structures, and landscape features can be examined. Geologic stops highlight the significance of the San Andreas and San Gregorio faults in the geologic history of the Point Reyes Peninsula. Historical information about the peninsula is also presented, including descriptions of the aftermath of the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. Figure 9-1. Map of the Point Reyes National Seashore area. Numbered stops include: 1) Visitor Center and Earthquake Trail, 2) Tomales Bay Trail, 3) Point Reyes Lighthouse, 4) Chimney Rock area, 5) Drakes Beach, 6) Tomales Bay State Park, 7) Kehoe Beach, 8) McClures Beach, 9) Mount Vision on Inverness Ridge, 10) Limantour Beach, 11) Olema Valley, 12) Palomarin Beach, 13) Duxbury Reef 14) Bolinas Lagoon/Stinson Beach area. Features include: Point Reyes (PR), Tomales Bay (TB), Drakes Estero (DE), Bolinas Lagoon (BL), Point Reyes Station (PRS), San Rafael (SR), and San Francisco (SF), Lucas Valley Road (LVR), and Sir Francis Drake Boulevard (SFDB). -

C:\Boatlists\Boatlistdraft-2021.Xlsx Boat Name Owner Prefix Sail No

C:\BoatLists\boatlistdraft-2021.xlsx Boat Name Owner Prefix Sail No. Suffix Hull Boat Type Classification Abraham C 2821 RS Feva XL Sailing Dinghy Dunikolu Adams R 10127 Wayfarer Sailing Dinghy Masie Mary Adlington CPLM 18ft motorboat Motor Boat Isla Rose Adlington JPN Tosher Sailing Boat Demelza Andrew JA 28 Heard 28 Sailing Boat Helen Mary Andrew KC 11 Falmouth Working Boat Sailing Boat Mary Ann Andrew KC 25 Falmouth Working Boat Sailing Boat Verity Andrew N 20 Sunbeam Sailing Boat West Wind Andrew N 21 Tosher 20 Sailing Boat Andrews K 208210 white Laser 4.7 Sailing Dinghy Hermes Armitage AC 70 dark blue Ajax Sailing Boat Armytage CD RIB Motor Boat Alice Rose Ashworth TGH Cockwell's 38 Motor Boat Maggie O'Nare Ashworth TGH 10 Cornish Crabber Sailing Cruiser OMG Ashworth* C & G 221 Laser Pico Sailing Dinghy Alcazar Bailey C Motor Boat Bailey C RS Fevqa Sailing Dinghy Dither of Dart Bailey T white Motor Sailer Coconi Barker CB 6000 Contessa 32 Sailing Cruiser Diana Barker G Rustler 24 Sailing Boat Barker G 1140 RS200 Sailing Dinghy Gemini Barnes E RIB Motor Boat Pelorus Barnes E GBR 3731L Arcona 380 Sailing Cruiser Barnes E 177817 Laser Sailing Dinghy Barnes F & W 1906 29er Sailing Dinghy Lady of Linhay Barnes MJ Catamaran Motor Boat Triumph Barnes MJ Westerly Centaur Sailing Cruiser Longhaul Barstow OG Orkney Longliner 16 Motor Boat Barö Barstow OG 2630 Marieholm IF-Boat Sailing Cruiser Rinse & Spin Bateman MCW 5919 Laser Pico Sailing Dinghy Why Hurry Batty-Smith JR 9312 Mirror Sailing Dinghy Natasha Baylis M Sadler 26 Sailing Cruiser