Lumbar Plexus Anatomy Within the Psoas Muscle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Netter's Anatomy Flash Cards – Section 7 – List 4Th Edition

Netter's Anatomy Flash Cards – Section 7 – List 4th Edition https://www.memrise.com/course/1577594/ Section 7 Lower Limb (72 cards) Plate 7-1 Hip (Coxal) Bone: Lateral View 1.1 Posterior superior iliac spine 1.2 Posterior inferior iliac spine 1.3 Greater sciatic notch 1.4 Body of ilium 1.5 Body of ischium 1.6 Ischial tuberosity 1.7 Pubic tubercle 1.8 Acetabulum 1.9 Iliac crest Plate 7-2 Hip (Coxal) Bone: Medial View 2.1 Wing (ala) of ilium (iliac fossa) 2.2 Pecten pubis (pectineal line) 2.3 Ramus of ischium 2.4 Lesser sciatic notch 2.5 Ischial spine 2.6 Articular surface (for sacrum) 2.7 Iliac tuberosity Plate 7-3 Hip Joint: Lateral View 3.1 Lunate (articular) surface of acetabulum 3.2 Articular cartilage 3.3 Head of femur 3.4 Ligament of head of femur (cut) 3.5 Obturator membrane 3.6 Acetabular labrum (fibrocartilaginous) Plate 7-4 Hip Joint: Anterior and Posterior Views 4.1 Iliofemoral ligament (Y ligament of Bigelow) 4.2 Pubofemoral ligament 4.3 Iliofemoral ligament 4.4 Ischiofemoral ligament Plate 7-5 Femur 5.1 Greater trochanter 5.2 Shaft (body) 5.3 Lateral epicondyle 5.4 Lateral condyle 5.5 Medial condyle 5.6 Medial epicondyle 5.7 Adductor tubercle 5.8 Linea aspera (Medial lip; Lateral lip) 5.9 Lesser trochanter 5.10 Intertrochanteric crest 5.11 Neck 5.12 Head Plate 7-6 Tibia and Fibula 6.1 Lateral condyle 6.2 Apex, Head, and Neck of fibula 6.3 Fibula 6.4 Lateral malleolus 6.5 Medial malleolus 6.6 Tibia 6.7 Tibial tuberosity 6.8 Medial condyle 6.9 Superior articular surfaces (medial and lateral facets) 6.10 Malleolar fossa of lateral -

33. Spinal Nerves. Cervical Plexus

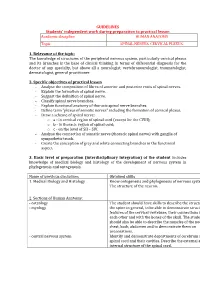

GUIDELINES Students’ independent work during preparation to practical lesson Academic discipline HUMAN ANATOMY Topic SPINAL NERVES. CERVICAL PLEXUS. 1. Relevance of the topic: The knowledge of structures of the peripheral nervous system, particularly cervical plexus and its branches is the base of clinical thinking in terms of differential diagnosis for the doctor of any specialty, but above all a neurologist, vertebroneurologist, traumatologist, dermatologist, general practitioner. 2. Specific objectives of practical lesson - Analyse the composition of fibres of anterior and posterior roots of spinal nerves. - Explain the formation of spinal nerve. - Suggest the definition of spinal nerve. - Classify spinal nerve branches. - Explain functional anatomy of thoracic spinal nerve branches. - Define term "plexus of somatic nerves" including the formation of cervical plexus. - Draw a scheme of spinal nerve: o а - in cervical region of spinal cord (except for the CVIII); o b - in thoracic region of spinal cord; o c - on the level of SII – SIV. - Analyse the connection of somatic nerve (thoracic spinal nerve) with ganglia of sympathetic trunk. - Create the conception of grey and white connecting branches in the functional aspect. 3. Basic level of preparation (interdisciplinary integration) of the student includes knowledge of medical biology and histology of the development of nervous system in phylogenesis and ontogenesis. Name of previous disciplines Obtained skills 1. Medical Biology and Histology Know ontogenesis and phylogenesis of nervous system. The structure of the neuron. 2. Sections of Human Anatomy: - osteology The student should have skills to describe the structure of - myology the spine in general, to be able to demonstrate structural features of the cervical vertebrae, their connections with each other and with the bones of the skull. -

The Supra-Iliac Anterior Quadratus Lumborum Block

Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01312-z REPORTS OF ORIGINAL INVESTIGATIONS The supra-iliac anterior quadratus lumborum block: a cadaveric study and case series Le bloc du muscle carre´ des lombes ante´rieur par approche supra-iliaque : une e´tude cadave´rique et une se´rie de cas Hesham Elsharkawy, MD, MBA, MSc . Kariem El-Boghdadly, MBBS, BSc, FRCA, EDRA, MSc . Theresa J. Barnes, MD, MPH . Richard Drake, PhD . Kamal Maheshwari, MD, MPH . Loran Mounir Soliman, MD . Jean-Louis Horn, MD . Ki Jinn Chin, MD, FRCPC Received: 9 July 2018 / Revised: 10 December 2018 / Accepted: 10 December 2018 Ó Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society 2019 Abstract Methods Ultrasound-guided bilateral supra-iliac anterior Purpose The local anesthetic injectate spread with fascial QL blocks were performed with 30 mL of India ink dye in plane blocks and corresponding clinical outcomes may six fresh adult cadavers. Cadavers were subsequently vary depending on the site of injection. We developed and dissected to determine distribution of the dye. In five evaluated a supra-iliac approach to the anterior quadratus patients undergoing hip surgery, a unilateral supra-iliac lumborum (QL) block and hypothesized that this single anterior QL block with 25 mL ropivacaine 0.5% followed injection might successfully block the lumbar and sacral by a continuous catheter infusion was performed. Patients plexus in cadavers and provide analgesia for patients were clinically assessed daily for block efficacy. undergoing hip surgery. Results The cadaveric injections showed consistent dye involvement of the majority of the branches of the lumbar plexus, including the femoral nerve, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, ilioinguinal nerve, and iliohypogastric Permission to use images was obtained from the Cleveland Clinic nerve. -

The Neuroanatomy of Female Pelvic Pain

Chapter 2 The Neuroanatomy of Female Pelvic Pain Frank H. Willard and Mark D. Schuenke Introduction The female pelvis is innervated through primary afferent fi bers that course in nerves related to both the somatic and autonomic nervous systems. The somatic pelvis includes the bony pelvis, its ligaments, and its surrounding skeletal muscle of the urogenital and anal triangles, whereas the visceral pelvis includes the endopelvic fascial lining of the levator ani and the organ systems that it surrounds such as the rectum, reproductive organs, and urinary bladder. Uncovering the origin of pelvic pain patterns created by the convergence of these two separate primary afferent fi ber systems – somatic and visceral – on common neuronal circuitry in the sacral and thoracolumbar spinal cord can be a very dif fi cult process. Diagnosing these blended somatovisceral pelvic pain patterns in the female is further complicated by the strong descending signals from the cerebrum and brainstem to the dorsal horn neurons that can signi fi cantly modulate the perception of pain. These descending systems are themselves signi fi cantly in fl uenced by both the physiological (such as hormonal) and psychological (such as emotional) states of the individual further distorting the intensity, quality, and localization of pain from the pelvis. The interpretation of pelvic pain patterns requires a sound knowledge of the innervation of somatic and visceral pelvic structures coupled with an understand- ing of the interactions occurring in the dorsal horn of the lower spinal cord as well as in the brainstem and forebrain. This review will examine the somatic and vis- ceral innervation of the major structures and organ systems in and around the female pelvis. -

35. Lumbar Plexus. Sacral Plexus. Coccygeal Plexus

GUIDELINES Students’ independent work during preparation to practical lesson Academic discipline HUMAN ANATOMY Topic LUMBAR PLEXUS. SACRAL PLEXUS. COCCYGEAL PLEXUS 1. Relevance of the topic Lumbar, sacral and coccygeal plexuses innervate the skin of the abdomen, lower back and lower extremities and all the muscles of the lower limbs. Acquired knowledge is the basis for many fields of practical medicine, such as neurology, surgery and traumatology. 2. Specific objectives After the lesson the student should know and be able to: - describe the sources of the formation of the lumbar plexus; - classify the nerves of the lumbar plexus; - to be able to demonstrate and define the branches of the lumbar plexus; - describe sources of sacral plexus formation; - classify sacral plexus nerves; - be able to demonstrate and identify short and long branches of the sacral plexus; - describe the sources of formation coccygeal plexus; - classify coccygeal plexus nerves; - be able to demonstrate and identify branches of coccygeal plexus; - to explain the innervation of muscles and skin in the areas of the lower back and lower extremity. 3. Basic level of preparation For practical this lesson a student should know and be able: - to know the anatomy of the spine, pelvis, lower extremities; - to analyze and show large and small pelvis, their bones; - to analyze and demonstrate bones and joints of the lower limbs; - to demonstrate muscles of the abdomen, perineum, pelvic girdle and lower limbs; - to know the anatomy (external and internal structure) of the spinal cord; - to know the spinal nerve anatomy. 4. Tasks for independent work during preparation for the classes 4.1. -

Quadratus Lumborum Blocks

REGIONAL ANAESTHESIA Tutorial433 Quadratus Lumborum Blocks Ro´ isı´ n Nee†1, John McDonnell2 1Regional Fellow, Galway University Hospital, Galway, Ireland 2Consultant Anaesthetist, Galway University Hospital, Galway, Ireland Edited by: Dr. Su Cheen Ng, University College Hospital London, UK Dr. Gillian Foxall, Consultant Anaesthetist, Royal Surrey County Hospital, Guildford, UK †Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] Published 29 September 2020 KEY POINTS Quadratus lumborum blocks (QLB) are a variation on transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks. Four different approaches to ultrasound-guided QLB have been described. QLB can be used to provide adjuvant analgesia for abdominal, orthopaedic, gynaecological and urological surgery. They can be performed in the lateral or supine position with a wedge under the patient’s hip. The shamrock sign of the psoas, erector spinae and the quadratus lumborum muscles around the transverse process on ultrasound allows identification of the needle insertion point. INTRODUCTION Dr. Rafa Blanco first described quadratus lumborum blocks (QLBs) in 20071 as a ‘‘no pops’’ transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block. It has been proposed as a more consistent method of accomplishing somatic as well as visceral analgesia of the abdomen than the TAP block and may provide an extended sensory blockade between T4 and L1. It can be used as an adjuvant technique for analgesia but does not provide adequate blockade to be used for anaesthesia. The QLB was developed to address the fact that as ultrasound imaging for regional anaesthesia has become more widespread, the tendency has been to move the injection point of the TAP block more anterior on the abdominal wall as compared with the original landmark technique, which is at the Triangle of Petit. -

Sonographic Tracking of Trunk Nerves: Essential for Ultrasound-Guided Pain Management and Research

Journal name: Journal of Pain Research Article Designation: Perspectives Year: 2017 Volume: 10 Journal of Pain Research Dovepress Running head verso: Chang et al Running head recto: Sonographic tracking of trunk nerve open access to scientific and medical research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S123828 Open Access Full Text Article PERSPECTIVES Sonographic tracking of trunk nerves: essential for ultrasound-guided pain management and research Ke-Vin Chang1,2 Abstract: Delineation of architecture of peripheral nerves can be successfully achieved by Chih-Peng Lin2,3 high-resolution ultrasound (US), which is essential for US-guided pain management. There Chia-Shiang Lin4,5 are numerous musculoskeletal pain syndromes involving the trunk nerves necessitating US for Wei-Ting Wu1 evaluation and guided interventions. The most common peripheral nerve disorders at the trunk Manoj K Karmakar6 region include thoracic outlet syndrome (brachial plexus), scapular winging (long thoracic nerve), interscapular pain (dorsal scapular nerve), and lumbar facet joint syndrome (medial branches Levent Özçakar7 of spinal nerves). Until now, there is no single article systematically summarizing the anatomy, 1 Department of Physical Medicine sonographic pictures, and video demonstration of scanning techniques regarding trunk nerves. and Rehabilitation, National Taiwan University Hospital, Bei-Hu Branch, In this review, the authors have incorporated serial figures of transducer placement, US images, Taipei, Taiwan; 2National Taiwan and videos for scanning the nerves in the trunk region and hope this paper helps physicians University College of Medicine, familiarize themselves with nerve sonoanatomy and further apply this technique for US-guided Taipei, Taiwan; 3Department of Anesthesiology, National Taiwan pain medicine and research. -

The Spinal Cord and Spinal Nerves

14 The Nervous System: The Spinal Cord and Spinal Nerves PowerPoint® Lecture Presentations prepared by Steven Bassett Southeast Community College Lincoln, Nebraska © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. Introduction • The Central Nervous System (CNS) consists of: • The spinal cord • Integrates and processes information • Can function with the brain • Can function independently of the brain • The brain • Integrates and processes information • Can function with the spinal cord • Can function independently of the spinal cord © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. Gross Anatomy of the Spinal Cord • Features of the Spinal Cord • 45 cm in length • Passes through the foramen magnum • Extends from the brain to L1 • Consists of: • Cervical region • Thoracic region • Lumbar region • Sacral region • Coccygeal region © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. Gross Anatomy of the Spinal Cord • Features of the Spinal Cord • Consists of (continued): • Cervical enlargement • Lumbosacral enlargement • Conus medullaris • Cauda equina • Filum terminale: becomes a component of the coccygeal ligament • Posterior and anterior median sulci © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. Figure 14.1a Gross Anatomy of the Spinal Cord C1 C2 Cervical spinal C3 nerves C4 C5 C 6 Cervical C 7 enlargement C8 T1 T2 T3 T4 T5 T6 T7 Thoracic T8 spinal Posterior nerves T9 median sulcus T10 Lumbosacral T11 enlargement T12 L Conus 1 medullaris L2 Lumbar L3 Inferior spinal tip of nerves spinal cord L4 Cauda equina L5 S1 Sacral spinal S nerves 2 S3 S4 S5 Coccygeal Filum terminale nerve (Co1) (in coccygeal ligament) Superficial anatomy and orientation of the adult spinal cord. The numbers to the left identify the spinal nerves and indicate where the nerve roots leave the vertebral canal. -

The Furcal Nerve Revisited Nerve Roots Should Be Suspected and Actively Investigated in All Failed Back Surgeries.2 It Also Correspondence: Nanjundappa S

Orthopedic Reviews 2014; volume 6:5428 The furcal nerve revisited nerve roots should be suspected and actively investigated in all failed back surgeries.2 It also Correspondence: Nanjundappa S. minimizes risk of potential litigations and its Harshavardhana, 2A Albert Road, Gourock PA19 Nanjundappa S. Harshavardhana,1 socio-economic burden thereof. Selective 1NH, Scotland, United Kingdom. Harshad V. Dabke2 nerve root blocks (SNRB) is of both diagnostic Tel.: +44.743.254.7084 - Fax: +44.147.550.4434. 1Inverclyde Royal Hospital, Greenock; and therapeutic utility in functional diagnosis E-mail: [email protected] 2Salisbury District Hospital, Wiltshire, 4 of radicular symptoms. Dorsal root ganglion Key words: lumbosacral plexus, furcal nerve, United Kingdom (DRG) and spinal nerve is targeted and the radiculopathy, atypical sciatica. epiradicular sheath is bathed with a local anesthetic. Care is taken to avoid placement of Acknowledgements: the authors would like to needle tip beyond DRG (i.e. at 6-o’clock in rela- thank Dr. Ensor E Transfeldt MD, FACS, attending Abstract tion to pedicle) which may ca use a potential spinal surgeon. Twin cities spine center, dural puncture.4 The DRG is inferior to pedicle Minneapolis, MN, U.S.A for enlightening us 1 about this entity. Atypical sciatica and discrepancy between in 90% of cases (medial 2%; inferolateral 8%). clinical presentation and imaging findings is a Contributions: the authors contributed equally. dilemma for treating surgeon in management of lumbar disc herniation. It also constitutes Conflict of interests: the authors declare no ground for failed back surgery and potential lit- Anatomy potential conflict of interests. igations thereof. Furcal nerve (Furcal = The lumbar plexus is located within the Received for publication: 9 April 2014. -

Ultrasound Guided Pain Procedures for the Physiatrist

Ultrasound Guided Pain Procedures For The Physiatrist Matthew J. Pingree, MD Division of Pain Medicine Joint Appointment in the departments of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and Anesthesiology Mayo Clinic, Rochester [email protected] Disclosure Relevant Financial Relationship(s) None Off Label Usage None. Why US for Imaging? The ASRA Evidence-Based Medicine Assessment of Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Executive Summary (Reg Anesth Pain Med 201:35: S1-9) . US superior to or equal – none found US to be dangerous or inferior . Most serious of complications (permanent nerve injury and LAST) too rare . Statistical advantage – not necessarily clinical advantage . No evidence US eliminates complications – limited data suggests complication rates similar . Poor technique, failure to image needle or novice behavior may increase risk! . No literature on US in specific patient populations (Pediatrics, DM, chemotherapy neuropathy) . US significant advance but does not lessen responsibility for using time proven strategies Ten Basic Skills 1) Visualize key landmark structures such as vascular, muscular, bony structures 2) Identify target structures on short-axis imaging as well as long axis if appropriate 3) Survey the target area in general checking for anatomic variations prior to needle intervention 4) Plan for a safe needling approach 5) Maintain an aseptic technique 6) Follow needle advancement under real-time visualization 7) Consider a secondary confirmation technique, such as nerve stimulation for regional anesthesia or fluoroscopy for pain interventions 8) Inject a small local anesthetic volume as a test solution to rule out unintentional/intravascular injection 9) Make necessary needle adjustments to ensure proper spread of local anesthetic and other injected agents 10) Maintain traditional safety guidelines. -

Lumbar and Sacral Plexuses

Lumbar and Sacral Plexuses Dr. Heba Kalbouneh Associate Professor of Anatomy and Histology Structure of Spinal Nerves: Somatic Pathways dorsal dorsal root ramus spinal nerve somatic sensory nerve CNS inter- neuron ventral somatic ramus motor nerve ventral root Mixed Spinal Nerve Structure of Spinal Nerves: Dorsal & Ventral Rami dorsal ramus spinal nerve somatic sensory nerve somatic Territory of Dorsal Rami ventral (everything else, but head, ramus motor innervated by ventral rami) nerve Stern Essentials of Gross Anatomy Nerves of the The lumbar plexus lower limb L1-L4 Is formed by the ventral rami of the upper four lumbar nerves in the substance of psoas major muscle It also receives a contribution from T12 (subcostal) nerve 2 main nerves Femoral nerve Obturator nerve L1 L2 4 small nerves L3 L4 Ilio-hypogastric nerve Ilio-inguinal nerve Genitofemoral nerve Lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh Ilio-hypogastric nerve L1 L2 Ilio-inguinal nerve L3 Genitofemoral Lateral cutaneous L4 nerve of the thigh nerve L5 Femoral nerve Obturator nerve Ilio-hypogastric nerve Each nerve of the lumber plexus emerges (exits) from the substance of Ilio-inguinal nerve the psoas major muscle as follows: L1 L2 Lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh L3 Genitofemoral L4 nerve L5 Femoral nerve Obturator nerve Ilio-hypogastric nerve L1 Ilio-inguinal nerve The ilio-hypogastric and ilio-inguinal L1 nerves arise as a single trunk from the L2 ventral ramus of L1 L3 Either before or soon after emerging from the lateral border of the psoas L4 major muscle, this single trunk -

Posterior Abdominal Wall- I (Muscles & Nerves)

Posterior Abdominal wall- I (Muscles & nerves) Dr Garima Sehgal Associate Professor Department of Anatomy King George’s Medical University DISCLAIMER: • The presentation includes images which are either hand drawn or have been taken from google images or books. • They are being used in the presentation only for educational purpose. • The author of the presentation claims no personal ownership over images taken from books or google images. • However, the hand drawn images are the creation of the author of the presentation Learning Objectives By the end of this teaching session you should be able to- • Describe the muscles of posterior abdominal wall (origin, insertion, actions, nerve supply) • Enumerate the nerves of the posterior abdominal wall • Describe the lumbar plexus (location , formation , branches) Understanding the anatomical reconstruction Muscles of posterior abdominal wall Skeletal Background Ligamentous background Musculofascial Background 1. T 12 vertebra th 1. Iliolumbar ligament 2. 12 rib 2. Anterior longitudnal 3. L 1 – L5 vertebrae ligament 1. Psoas major muscle 4. Iliac crest and iliac 3. Ventral sacroiliac fossa and fascia ligament 2. Quadratus lumborum 3. Iliacus and fascia iliaca 4. Psoas minor Psoas major Occupies 3 regions- abdomen, false pelvis & upper thigh Origin – 14 fleshy strips Continous attachment from T12(lower border) to L5 (upper border) 1. discs above 5 lumbar vertebrae 2. adjoining parts of vertebral bodies 3. 4 fibrous arches across the sides of upper 4 lumbar vertebrae Actions – i. Chief flexor of