Project Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impact De La Mise E Chance Dans La Régio

Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de République du Mali la Recherche Scientifique ------------- ----------------------- Un Peuple – Un But – Une Foi Universités des Sciences, des Techniques et des Te chnologies de Bamako (USTTB) --------------- Thèse N°…… Faculté de Médecine et d’Odonto -Stomatologie Année Universitaire 2011/2012 TITRE : Impact de la mise en œuvre de la stratégie chance dans la région de Mopti : résultat de l’enquête 2011 Thèse présentée et soutenue publiquement le………………………/2013 Devant la Faculté de Médecine et d’Odonto -Stomatologie Par : M. Boubou TRAORE Pour obtenir le grade de Docteur en Médecine (Diplôme d’Etat) JURY : Président : Pr Tiéman COULIBALY Membre : Dr Alberd BANOU Co-directeur : Dr Mamadou DEMBELE Directeur de thèse : Pr Sanoussi BAMANI Thèse de Médecine Boubou TRAORE 1 DEDICACES A MA MERE : Fanta FANE Je suis fier de t’avoir comme maman Tu m’as appris à accepter et aimer les autres avec leurs différences L’esprit de tolérance qui est en moi est le fruit de ta culture Tu m’as donné l’amour d’une mère et la sécurité d’un père. Tu as été une mère exemplaire et éducatrice pour moi. Aujourd’hui je te remercie d’avoir fait pour moi et mes frères qui nous sommes. Chère mère, reçois, à travers ce modeste travail, l’expression de toute mon affection. Q’ALLAH le Tout Puissant te garde longtemps auprès de nous. A MON PERE : Feu Tafara TRAORE Ton soutien moral et matériel ne m’as jamais fait défaut. Tu m’as toujours laissé dans la curiosité de te connaitre. Tu m’as inculqué le sens du courage et de la persévérance dans le travail A MON ONCLE : Feu Yoro TRAORE Ton soutien et tes conseils pleins de sagesse m’ont beaucoup aidé dans ma carrière scolaire. -

Elephant Conservation in Mali: Engaging with a Socio-Ecological

Empowering Communities to Conserve the Mali Elephants in Times of War and Peace Dr Susan Canney, Director of the Mali Elephant Project Research Associate, University of Oxford Lake Banzena by Carlton Ward Jr How have these elephants survived? •Internationally important elephant population •12% of all West African elephants •Most northerly in Africa •Undertake the longest &most unusual migration of all elephants Save the Elephants’ GPS collar data 3 elephants 2000-2001 9 elephants 2008-2009 Zone of Intervention The elephant migration route (in brown) in relation to West Africa. The area of project intervention comprises the elephant range and extends to the Niger river (in blue) Timbuktu 100km A typical small lake (with fishing nets in the foreground) Timbuktu 100km Photograph by Carlton Ward Jr Photograph by Carlton Ward Jr Increasing human occupation and activity accelerating through 1990s and 2000s Population density by commune 1997 census data Ouinerden #### Rharous #### ###### # # ## Bambara ## # Djaptodji Maounde N'Tillit Inadiatafane ###### #### # ## # ## #### ######################### # ###### ## ### ### ###################################################################################################################################################################################### # #### ############# ## Gossi #### ################################################# # # # ####### ################# ## ######## ########### ##### ######## # # ########### ##### ### ## ##################################################################################################################################################################################################### -

M700kv1905mlia1l-Mliadm22305

! ! ! ! ! RÉGION DE MOPTI - MALI ! Map No: MLIADM22305 ! ! 5°0'W 4°0'W ! ! 3°0'W 2°0'W 1°0'W Kondi ! 7 Kirchamba L a c F a t i Diré ! ! Tienkour M O P T I ! Lac Oro Haib Tonka ! ! Tombouctou Tindirma ! ! Saréyamou ! ! Daka T O M B O U C T O U Adiora Sonima L ! M A U R I T A N I E ! a Salakoira Kidal c Banikane N N ' T ' 0 a Kidal 0 ° g P ° 6 6 a 1 1 d j i ! Tombouctou 7 P Mony Gao Gao Niafunké ! P ! ! Gologo ! Boli ! Soumpi Koulikouro ! Bambara-Maoude Kayes ! Saraferé P Gossi ! ! ! ! Kayes Diou Ségou ! Koumaïra Bouramagan Kel Zangoye P d a Koulikoro Segou Ta n P c ! Dianka-Daga a ! Rouna ^ ! L ! Dianké Douguel ! Bamako ! ougoundo Leré ! Lac A ! Biro Sikasso Kormou ! Goue ! Sikasso P ! N'Gorkou N'Gouma ! ! ! Horewendou Bia !Sah ! Inadiatafane Koundjoum Simassi ! ! Zoumoultane-N'Gouma ! ! Baraou Kel Tadack M'Bentie ! Kora ! Tiel-Baro ! N'Daba ! ! Ambiri-Habe Bouta ! ! Djo!ndo ! Aoure Faou D O U E N T Z A ! ! ! ! Hanguirde ! Gathi-Loumo ! Oualo Kersani ! Tambeni ! Deri Yogoro ! Handane ! Modioko Dari ! Herao ! Korientzé ! Kanfa Beria G A O Fraction Sormon Youwarou ! Ourou! hama ! ! ! ! ! Guidio-Saré Tiecourare ! Tondibango Kadigui ! Bore-Maures ! Tanal ! Diona Boumbanke Y O U W A R O U ! ! ! ! Kiri Bilanto ! ! Nampala ! Banguita ! bo Sendegué Degue -Dé Hombori Seydou Daka ! o Gamni! d ! la Fraction Sanango a Kikara Na! ki ! ! Ga!na W ! ! Kelma c Go!ui a Te!ye Kadi!oure L ! Kerengo Diambara-Mouda ! Gorol-N! okara Bangou ! ! ! Dogo Gnimignama Sare Kouye ! Gafiti ! ! ! Boré Bossosso ! Ouro-Mamou ! Koby Tioguel ! Kobou Kamarama Da!llah Pringa! -

Régions De SEGOU Et MOPTI République Du Mali P! !

Régions de SEGOU et MOPTI République du Mali P! ! Tin Aicha Minkiri Essakane TOMBOUCTOUC! Madiakoye o Carte de la ville de Ségou M'Bouna Bintagoungou Bourem-Inaly Adarmalane Toya ! Aglal Razelma Kel Tachaharte Hangabera Douekiré ! Hel Check Hamed Garbakoira Gargando Dangha Kanèye Kel Mahla P! Doukouria Tinguéréguif Gari Goundam Arham Kondi Kirchamba o Bourem Sidi Amar ! Lerneb ! Tienkour Chichane Ouest ! ! DiréP Berabiché Haib ! ! Peulguelgobe Daka Ali Tonka Tindirma Saréyamou Adiora Daka Salakoira Sonima Banikane ! ! Daka Fifo Tondidarou Ouro ! ! Foulanes NiafounkoéP! Tingoura ! Soumpi Bambara-Maoude Kel Hassia Saraferé Gossi ! Koumaïra ! Kanioumé Dianké ! Leré Ikawalatenes Kormou © OpenStreetMap (and) contributors, CC-BY-SA N'Gorkou N'Gouma Inadiatafane Sah ! ! Iforgas Mohamed MAURITANIE Diabata Ambiri-Habe ! Akotaf Oska Gathi-Loumo ! ! Agawelene ! ! ! ! Nourani Oullad Mellouk Guirel Boua Moussoulé ! Mame-Yadass ! Korientzé Samanko ! Fraction Lalladji P! Guidio-Saré Youwarou ! Diona ! N'Daki Tanal Gueneibé Nampala Hombori ! ! Sendegué Zoumané Banguita Kikara o ! ! Diaweli Dogo Kérengo ! P! ! Sabary Boré Nokara ! Deberé Dallah Boulel Boni Kérena Dialloubé Pétaka ! ! Rekerkaye DouentzaP! o Boumboum ! Borko Semmi Konna Togueré-Coumbé ! Dogani-Beré Dagabory ! Dianwely-Maoundé ! ! Boudjiguiré Tongo-Tongo ! Djoundjileré ! Akor ! Dioura Diamabacourou Dionki Boundou-Herou Mabrouck Kebé ! Kargue Dogofryba K12 Sokora Deh Sokolo Damada Berdosso Sampara Kendé ! Diabaly Kendié Mondoro-Habe Kobou Sougui Manaco Deguéré Guiré ! ! Kadial ! Diondori -

Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019

FEWS NET Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019 MALI ENHANCED MARKET ANALYSIS JUNE 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’Famine views Early expressed Warning inSystem this publications Network do not necessarily reflect the views of the 1 United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgments FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Mali who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2019. Mali Enhanced Market Analysis. Washington, DC: FEWS NET. -

Spécialdfc Agriculture Externes Durable Àfaibles Apports MELCA Bougouma Mbaye Fall Et Ousmane Traoré Diagne

I T O I N D É A F R I Q U E F R A NC E OPHON vrier pcial Revue sur l’Agriculture durable à faibles apports externes 1 La rédaction a mis le plus grand soin à s’assurer que le contenu de la présente revue est aussi exact que possible. Mais, en dernier ressort,seuls les auteurs sont responsables du contenu Agriculture durable à faibles apports externes de chaque article. N° Spécial DFC AGRIDAPE est l’édition régionale Les opinions exprimées dans cette Afrique francophone du magazine Farming revue n’engagent que leurs auteurs. Matters produit par le Réseau AgriCultures. La rédaction encourage les lecteurs ISSN N°0851-7932 à photocopier et à faire circuler ces articles. Vous voudrez bien cependant citer l’auteur et la source et nous envoyer un exemplaire de votre publication. Édité par : IED Afrique 24, Sacré Coeur III – Dakar BP : 5579 Dakar-Fann, Sénégal Chères lectrices, chers lecteurs, Téléphone : +221 33 867 10 58 - Fax : +221 33 867 10 59 E-mail : [email protected] - Site Web : www.iedafrique.org La revue AGRIDAPE vous revient avec un nouveau Coordonnateur : Birame Faye numéro spécial. Celui-ci porte un modèle, Comité éditorial : un mécanisme innovant qui a permis à des Bara Guèye, Mamadou Fall, Rokhaya Faye, Momath Talla Ndao, communautés à la base et à des collectivités Aly Bocoum, Yacouba Dème, Lancelot Soumelong Ehode, Djibril Diop, Ced Hesse, Yamadou Diallo territoriales d’accéder à des financements dans le cadre de la mise en œuvre du projet Décentralisation Ce numéro a été réalisé avec l’appui de Amadou Ndiaye (Sénégal) des Fonds Climat (DFC) à Mopti (Mali) et à Kaffrine et Abdoulaye Cissé (Mali) (Sénégal), dans le but de renforcer les capacités Administration : de résilience des populations locales face au Maïmouna Dieng Lagnane changement climatique. -

Pnr 2015 Plan Distribution De

Tableau de Compilation des interventions Semences Vivrières mise à jour du 03 juin 2015 Total semences (t) Total semences (t) No. total de la Total ménages Total Semences (t) Total ménages Total semences (t) COMMUNES population en Save The Save The CERCLE CICR CICR FAO REGIONS 2015 (SAP) FAO Children Children TOMBOUCTOU 67 032 ALAFIA 15 844 BER 23 273 1 164 23,28 BOUREM-INALY 14 239 1 168 23,36 LAFIA 9 514 854 17,08 TOMBOUCTOU SALAM 26 335 TOMBOUCTOU TOTAL 156 237 DIRE 24 954 688 20,3 ARHAM 3 459 277 5,54 BINGA 6 276 450 9 BOUREM SIDI AMAR 10 497 DANGHA 15 835 437 13 GARBAKOIRA 6 934 HAIBONGO 17 494 482 3,1 DIRE KIRCHAMBA 5 055 KONDI 3 744 SAREYAMOU 20 794 1 510 30,2 574 3,3 TIENKOUR 8 009 TINDIRMA 7 948 397 7,94 TINGUEREGUIF 3 560 DIRE TOTAL 134 559 GOUNDAM 15 444 ALZOUNOUB 5 493 BINTAGOUNGOU 10 200 680 6,8 ADARMALANE 1 172 78 0,78 DOUEKIRE 22 203 DOUKOURIA 3 393 ESSAKANE 13 937 929 9,29 GARGANDO 10 457 ISSA BERY 5 063 338 3,38 TOMBOUCTOU KANEYE 2 861 GOUNDAM M'BOUNA 4 701 313 3,13 RAZ-EL-MA 5 397 TELE 7 271 TILEMSI 9 070 TIN AICHA 3 653 244 2,44 TONKA 65 372 190 4,2 GOUNDAM TOTAL 185 687 RHAROUS 32 255 1496 18,7 GOURMA-RHAROUS TOMBOUCTOU BAMBARA MAOUDE 20 228 1 011 10,11 933 4,6 BANIKANE 11 594 GOSSI 29 529 1 476 14,76 HANZAKOMA 11 146 517 6,5 HARIBOMO 9 045 603 7,84 419 12,2 INADIATAFANE 4 365 OUINERDEN 7 486 GOURMA-RHAROUS SERERE 10 594 491 9,6 TOTAL G. -

Multi-Sectoral Rapid Assessment Report Rapport D'évaluation

Multi-sectoral Rapid Assessment Report TRapport imbuktu d’évaluation rapide multisectorielle Emergency Team Leader Pacifique Kigongwe Tombouctou [email protected] Acknowledgements International Medical Corps’ Emergency Response Team would like to thank all the actors that facilitated the collection of information in this rapid assessment. In particular, thank you to the Acting Head of the Regional Health Department, partners and NGOs involved in the Timbuktu region: MSF, Solidarités, Handicap International, AVSF, the ICRC; and investigators who provided data collection at the household level as well as key informants and community volunteers who participated in the focus groups. 2 ©2013 International Medical Corps Summary In the current crisis in northern Mali, International Medical Corps conducted a multi-sectoral assessment in the Timbuktu region between February 1st and February 4th, 2013, the main points are summarized below: Health Serious failures of the health system have occurred during the period when the Northern district was controlled by rebel groups, for the following reasons: The Regional Health Department was looted and health personnel and members of communities health associations (ASACOs) have fled; Disruption of the supply chain for medication, nutritional inputs, and fuel; Disruption of the cold chain; Pillaging of buildings and equipment (ambulances, solar panels) The access to health services was deeply compromised for the inhabitants of the districts of Timbuktu, Goundam, Gourma- Rharous, and Niafunké. Three partners support the health services: MSF (since February 2012), Alima (mainly for the district of Diré) and the ICRC. However, they do not cover all the needs, and the access to health care remains a problem for the populations given the distances and difficulty of access. -

AVERTISSEMENT Les Tableaux Qui Suivent N'ont Pas De Valeur Juridique. Ils Sont Une Compilation Des Récépissés Affichés De

AVERTISSEMENT Les tableaux qui suivent n’ont pas de valeur juridique. Ils sont une compilation des récépissés affichés devant le bureau de vote après le dépouillement. Ils ont un caractère purement informatif et ne sauraient être utilisés à d’autre fin. ELECTION DU PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE SCRUTIN DU 29 JUILLET 2018 CERCLE DE GOURMA RHAROUS: RESULTATS BUREAU PAR BUREAU CERCLE COMMUNE BUREAU VOTANTS BN VOIX N°1 N°2 N°3 N°4 N°5 N°6 N°7 N°8 N°9 N°10 N°11 N°12 N°13 N°14 N°15 N°16 N°17 N°18 N°19 N°20 N°21 N°22 N°23 N°24 GOURMA-RHAROUS RHAROUS RHAROUS SECOND CYCLE-001 136 7 129 42 3 3 0 2 3 64 1 0 2 0 4 0 2 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 GOURMA-RHAROUS RHAROUS ECOLE RAROUS II-001 197 13 184 52 5 4 2 4 6 78 2 0 0 1 7 1 6 1 0 4 1 1 3 2 2 0 2 GOURMA-RHAROUS RHAROUS ECOLE RAROUS II-002 201 17 184 60 8 9 1 2 3 69 1 3 0 3 5 2 2 0 4 7 1 1 0 2 1 0 0 GOURMA-RHAROUS RHAROUS ECOLE RAROUS II-003 220 13 207 78 3 3 2 3 5 75 2 1 0 3 13 3 1 0 0 8 0 1 0 4 0 2 0 GOURMA-RHAROUS RHAROUS ECOLE RAROUS II-004 209 10 199 41 11 7 1 2 3 101 2 2 1 3 6 0 5 1 0 2 1 1 0 9 0 0 0 GOURMA-RHAROUS RHAROUS ECOLE RAROUS II-005 174 1 173 39 4 3 1 3 1 100 0 2 2 0 5 3 3 0 0 1 1 0 1 3 1 0 0 GOURMA-RHAROUS RHAROUS ECOLE RAROUS II-006 215 11 204 40 8 2 3 11 2 111 3 0 0 1 7 2 5 0 0 3 0 0 3 2 0 0 1 GOURMA-RHAROUS RHAROUS ECOLE RAROUS II-007 220 14 206 49 5 3 3 8 5 103 2 2 0 0 5 2 3 0 2 1 2 3 3 4 0 0 1 GOURMA-RHAROUS RHAROUS ALHADO KOIRA-001 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 GOURMA-RHAROUS RHAROUS AWILO KOIRA-001 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 GOURMA-RHAROUS -

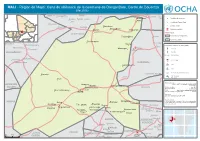

Ocha Mopti Commune Da

MALI - Région de Mopti: Carte de référence de la commune de Dangol Bore, Cercle de Douentza (Mai 2016) DofinaSAHARA Oualo Tambeni Dindia OCCIDENTAL Dianguinare Deri ALGERIE Kersani Senore Takouti Sobo Ouro-diam Chef lieu de commune Boukourintie Allah Noradji Dari Localité de Dangol Bore Sare Tombouctou MAURITANIE Boukourintie-oKidaluro Dimango N'dissore Mounkeye Localité voisine Bagui Sounteye Norkala Magoubeye Gao Hororo N'doumpa Structure sanitaire Mopti Akka Route Korientzé NIGER KayesKera Segou DJAPTODJI SENEGAL KoulikouroKorientzé Korientze Commune de Dangol Bore Bamako BURKINA FASO Foulacriabes Ibrizaz GUINEE Sikasso NIGERIA Commune voisine GHANA BENIN COTE D'IVOIRE TOGO Bore-maures Kel-eguel Massama Youna Moussokourare Population estimée en 2015 (DNP) Tanal M'bessema CSCOM Tiecourare Madougou 16 190 DIONA KOROMBANA 16 359 Densité: 13 hb/Km2 Gouloumbou Keretogo 1 CSCOM Madina-coura KORAROU Sansa-tounta ND ND 1 Ecole de première cycle Kerengo Diambara-mouda Goui 34 forages 45 puits Teye Nom de la carte: OUROUBE Niongolo OCHA_MOPTI_COMMUNE_DANGOL BORE Manko Gnimignama A3_20160516 DOUDE Falembougou DEBERE Date de création: Avril 2016 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Ouori-n'dounkoye CSCOM Web : http://mali.humanitarianresponse.info BORE Echelle nominale sur papier A3 : 1:250,000 Source(s): Données spatiales: DNCT, DNP, DTM Avertissements: Adioubata Les Nations Unies ne sauraient être tenues responsables KONNA Amba Bobowel de la qualité des limites, des noms et des désignations Dounkoy Ena-tioki Doumbara utilisés sur cette carte Tete-ompto Some Koira Noumboli Forgeron-issa Beri Batouma Ouro-lenga Kiro Noumori-soki Dimbatoro Tabako Songadji Koressana Dempari Bedjima Semari-dangani Nema Tiboki Ibissa Mougui Dembeli BORKO KOUBEWEL Nomgoro KOUNDIA Mello Adia CSCOM Dindari BORKO Temba-neri Neri KENDIE Tim-tam DIAMNATI LOWOL DOGANI BERE Endeguem 0 3.5 7 Km GUEOU Sassambourou CONFES- Olkia Menthy Oume SIONNEL Saoura-kom. -

Peuplement Humain Et Paléoenvironnement En Afrique De L’Ouest: Résultats De La Neuvième Année De Recherches Eric Huysecom Et Al.*

SLSA Jahresbericht 2006 Peuplement humain et paléoenvironnement en Afrique de l’Ouest: résultats de la neuvième année de recherches Eric Huysecom et al.* * Eric HuysecomI 1. Présentation générale Sylvain OzainneI 1.1. Les collaborations Caroline Robion-Brunner I Les travaux scientifiques conduits lors de cette neuvième année du programme de re- Anne Mayor I cherche international et interdisciplinaire Peuplement humain et paléoenvironnement Aziz BalloucheII en Afrique de l’Ouest ont permis d’apporter de nouvelles données importantes pour Nafogo CoulibalyIII une meilleure connaissance du passé ouest-africain. Dix-sept chercheurs et neuf étu- Nema GuindoIV diants ont participé aux recherches de terrain: Daouda KéitaIV Yann Le DrezenII 1. L’équipe suisse a rassemblé des scientifiques appartenant à deux institutions: Laurent LespezII a. la Mission Archéologique et Ethnoarchéologique Suisse en Afrique de l’Ouest Katharina NeumannV (MAESAO) du Département d’anthropologie et d’écologie de l’Université de Ge- Barbara EichhornV nève, avec quatre chercheurs de l’Université (Eric Huysecom, Sylvain Ozainne, Ka- Michel RasseVI tia Schaer et Anne Mayor), une doctorante (Caroline Robion-Brunner), une di- Katia SchaerI plômante (Camille Selleger), deux étudiantes (Aurélie Gottraux et Aurélie Terrier) Camille Selleger I et un étudiant (David Codeluppi); une collaboratrice du département, Elvyre Mar- Vincent SerneelsVII tinez, a assuré sur le terrain la documentation photographique des différentes Sylvain SorianoVIII équipes. Aurélie Terrier I b. l’Unité de minéralogie et pétrographie du Département de géosciences de l’Uni- Boubacar D. Traoré IV versité de Fribourg, avec un chercheur (Vincent Serneels). Sébastien Perret, doc- Chantal Tribolo IX torant, n’a pas participé aux missions de terrain afin de progresser dans les ana- lyses de laboratoire et la rédaction de son travail de thèse. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

MINISTERE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT REPUBLIQUE DU MALI DE L’EAU ET DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT Un Peuple – Un But – Une Foi DIRECTION NATIONALE DES EAUX ET FORÊTS STRATEGIE NATIONALE ET PLAN D’ACTIONS POUR LA DIVERSITE BIOLOGIQUE, MALI DécembreOctobre 20132014 TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES FIGURES ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 LISTE DES TABLEAUX ................................................................................................................................................... 4 LISTE DES PHOTOS ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................................ 6 RESUME EXECUTIF....................................................................................................................................................... 8 PARTIE A : SITUATION DE LA DIVERSITE BIOLOGIQUE ................................................................................. 12 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................... 13 CHAPITRE I : PRESENTATION GENERALE DU MALI ..................................................................................................... 16