PROMISAM Final Technical Report, Covering the Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport Sur Les Moustiques De La République Du Mali

'. ORGANISATION DE· COORDINATION . ET DE' COOPERATION POUR· LA LUTTE CONTRE LES GRAlID:BiS ENn~UES',' ~=-=- . 'CENmE MURAZ'. ~.~~-" SECTION DI EàlTQrIIOLOGIE . JJ)APPORTSUR LES'I'lOU'JTIQUESDE LA'REPlTBLIQU8DU lmr ".. ( -=-=-:;;"=--:;-=-=-c:~~~=-r-.>::::>-=--=-::..~~=-=-- parHANONJacques, DIALLO Bellon, EYRAun Hà.rceli ~]YEI~OillîA AugÙstinetOUA110U Sylla "':'-"'000-':"'''' ., Les premières, observations concernant' les moustiques duBoudan sont: , .celles de IEMOAL en 1906 et de: BüUFFABD, en I908~ Depuis 'ces études diverses' pu.... blications .ont augmenté nos connaissances sur ce. sujet, .mais jUsqu 1 en I950 le nombre total des nouatLuesccnnus du:.:cll . était de-treize: sept Anopheles; ·un Aëdes, et cinq Culex, 'et les données existantes, concernaâenti-pi-esque unique- ment sur la répartition des' anophèles le long èLela vallée du Niger, avec quel.ques '' '. indications sur leurs gîtes larvaires et les lieux de repos des edul.tess. , 'Les enquêtes d tHOLSTEIN, 'menées pour 'leconipte du SeryiceGénéral . d"Hygiène ~Ifobile et. de Prophylaxie bu de l'Office du Niger ont' considérablement ,. augmenté nos connai'ssanoea .sur' la répartition des anophèles au Soudan~.enappo~ .tant également des indications préci.euses 'sur leUTS variatiClns saisonnières et . Leurs indices sporozoïtiques' danaTa régi,on de SEGOU. Les au:t~es moustiques ciui . · ont pu ~tre récoltés Lo'rsdes enquêtes d'HOLSTEIN sur .Les 'and'phèles n ' ont pas encore été .é'tu:diés. .' .. Des niises au point ont réceillIrlent ,été faites, gén6ralemen,t à' l'échelle de l'Afrique Occidentale, sur Laplupart des autres groupes d' àrthr,oPQdesd':tm-: portance médicale ouvétérânarre : tiques;.phlébotomes, tabanidés~ simlllies, et à .. · l 'heure où 1lOrganisationMondütle de la Santé :envisage l 'êradication du paludisme, dans toute l'Afrique, et où lès Instituts Pasteur; se préoccupent de pl\l.s en p.lus ". -

340102-Fre.Pdf (433.2Kb)

r 1 RAPPORT DE MISSION [-a mission que nous venons de terminer avait pour but de mener une enquête dans quelques localités du Mali pour avoir une idée sur la vente éventuelle de I'ivermectine au Mali et le suivi de la distribution du médicament par les acteurs sur le terrain. En effet sur ordre de mission No 26/OCPlZone Ouest du3l/01196 avec le véhicule NU 61 40874 nous avons debuté un périple dans les régions de Koulikoro, Ségou et Sikasso et le district de Bamako, en vue de vérifier la vente de l'ivermectine dans les pharmacies, les dépôts de médicament ou avec les marchands ambulants de médicaments. Durant notre périple, nous avons visité : 3 Régions : Koulikoro, Ségou, Sikasso 1 District : Bamako 17 Cercles Koulikoro (06 Cercles), Ségou (05 Cercles), Sikasso (06 Cercles). 1. Koulikoro l. Baraouli 1. Koutiala 2. Kati 2. Ségou 2. Sikasso 3. Kolokani 3. Macina 3. Kadiolo 4. Banamba 4. Niono 4. Bougouni 5. Kangaba 5. Bla 5. Yanfolila 6. Dioila 6. Kolondiéba avec environ Il4 pharmacies et dépôts de médicaments, sans compter les marchands ambulants se trouvant à travers les 40 marchés que nous avons eu à visiter (voir détails en annexe). Malgré notre fouille, nous n'avons pas trouvé un seul comprimé de mectizan en vente ni dans les pharmacies, ni dans les dépôts de produits pharmaceutiques ni avec les marchands ambulants qui ne connaissent d'ailleurs pas le produit. Dans les centres de santé où nous avons cherché à acheter, on nous a fait savoir que ce médicament n'est jamais vendu et qu'il se donne gratuitement à la population. -

Rapport Annuel 2016 Etat D'execution Des Activites

MINISTERE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT DE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI L’ASSAINISSEMENT ET DU ****************** DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLE ************* Un Peuple –Un But – Une Foi AGENCE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLE (AEDD) ************* PROGRAMME D’APPUI A L’ADAPTATION AUX CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES DANS LES COMMUNES LES PLUS VULNERABLES DES REGIONS DE MOPTI ET DE TOMBOUCTOU (PACV-MT) RAPPORT ANNUEL 2016 PACV-MT ETAT D’EXECUTION DES ACTIVITES Octobre 2016 ACRONYMES AEDD : Agence de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable AFB : Fonds d’Adaptation CCOCSAD : Comité Communale d’Orientation, de Coordination et de Suivi des Actions de Développement CLOCSAD : Comité Local d’Orientation, de Coordination et de Suivi des Actions de Développement CROCSAGD : Comité Régionale d’Orientation, de Coordination et de Suivi des Actions de Gouvernance et de Développement CEPA : Champs Ecoles Paysans Agroforestiers CEP : Champs Ecoles Paysans CNUCC : Convention Cadre des Nations Unies sur le Changement Climatique DAO : Dossier d’Appel d’Offres DCM : Direction de la Coopération Multilatérale DGMP : Direction Générale des Marchés Publics MINUSMA : Mission Multidimensionnelle Intégrée des Nations Unies pour la Stabilisation au Mali OMVF : Office pour le Mise en Valeur du système Faguibine PAM : Programme Alimentaire Mondial PDESC : Plan de développement Economique, Social et Culturel PTBA : Plan de Travail et de Budget Annuel PACV-MT : Programme d‘Appui à l‘Adaptation aux Changements Climatiques dans les Communes les plus Vulnérables des Régions de Mopti et de Tombouctou PK : Protocole de Kyoto PNUD : Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement TDR : Termes de références UGP : Unité de Gestion du Programme RAPPORT ANNUEL 2016 DU PACV-MT Page 2 sur 47 TABLE DES MATIERES ACRONYMES ............................................................................................................... -

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

FALAISES DE BANDIAGARA (Pays Dogon)»

MINISTERE DE LA CULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI *********** Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi DIRECTION NATIONALE DU ********** PATRIMOINE CULTUREL ********** RAPPORT SUR L’ETAT DE CONSERVATION DU SITE «FALAISES DE BANDIAGARA (Pays Dogon)» Janvier 2020 RAPPORT SUR L’ETAT ACTUEL DE CONSERVATION FALAISES DE BANDIAGARA (PAYS DOGON) (MALI) (C/N 516) Introduction Le site « Falaises de Bandiagara » (Pays dogon) est inscrit sur la Liste du Patrimoine Mondial de l’UNESCO en 1989 pour ses paysages exceptionnels intégrant de belles architectures, et ses nombreuses pratiques et traditions culturelles encore vivaces. Ce Bien Mixte du Pays dogon a été inscrit au double titre des critères V et VII relatif à l’inscription des biens: V pour la valeur culturelle et VII pour la valeur naturelle. La gestion du site est assurée par une structure déconcentrée de proximité créée en 1993, relevant de la Direction Nationale du Patrimoine Culturel (DNPC) du Département de la Culture. 1. Résumé analytique du rapport Le site « Falaises de Bandiagara » (Pays dogon) est soumis à une rude épreuve occasionnée par la crise sociopolitique et sécuritaire du Mali enclenchée depuis 2012. Cette crise a pris une ampleur particulière dans la Région de Mopti et sur ledit site marqué par des tensions et des conflits armés intercommunautaires entre les Dogons et les Peuls. Un des faits marquants de la crise au Pays dogon est l’attaque du village d’Ogossagou le 23 mars 2019, un village situé à environ 15 km de Bankass, qui a causé la mort de plus de 150 personnes et endommagé, voire détruit des biens mobiliers et immobiliers. -

Inventaire Des Aménagements Hydro-Agricoles Existants Et Du Potentiel Amenageable Au Pays Dogon

INVENTAIRE DES AMÉNAGEMENTS HYDRO-AGRICOLES EXISTANTS ET DU POTENTIEL AMENAGEABLE AU PAYS DOGON Rapport de mission et capitalisation d’expérienCe Financement : Projet d’Appui de l’Irrigation de Proximité (PAIP) Réalisation : cellule SIG DNGR/PASSIP avec la DRGR et les SLGR de la région de Mopti Bamako, avril 2015 Table des matières I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Méthodologie appliquée ................................................................................................................ 3 III. Inventaire des AHA existants et du potentiel aménageable dans le cercle de Bandiagara .......... 4 1. Déroulement des activités dans le cercle de Bandiagara ................................................................................... 7 2. Bilan de l’inventaire du cercle de Bandiagara .................................................................................................... 9 IV. Inventaire des AHA existants et du potentiel aménageable dans les cercles de Bankass et Koro 9 1. Déroulement des activités dans les deux cercles ............................................................................................... 9 2. Bilan de l’inventaire pour le cercle de Koro et Bankass ................................................................................... 11 Gelöscht: 10 V. Inventaire des AHA existants et du potentiel aménageable dans le cercle de Douentza ............. 12 VI. Récapitulatif de l’inventaire -

M700kv1905mlia1l-Mliadm22305

! ! ! ! ! RÉGION DE MOPTI - MALI ! Map No: MLIADM22305 ! ! 5°0'W 4°0'W ! ! 3°0'W 2°0'W 1°0'W Kondi ! 7 Kirchamba L a c F a t i Diré ! ! Tienkour M O P T I ! Lac Oro Haib Tonka ! ! Tombouctou Tindirma ! ! Saréyamou ! ! Daka T O M B O U C T O U Adiora Sonima L ! M A U R I T A N I E ! a Salakoira Kidal c Banikane N N ' T ' 0 a Kidal 0 ° g P ° 6 6 a 1 1 d j i ! Tombouctou 7 P Mony Gao Gao Niafunké ! P ! ! Gologo ! Boli ! Soumpi Koulikouro ! Bambara-Maoude Kayes ! Saraferé P Gossi ! ! ! ! Kayes Diou Ségou ! Koumaïra Bouramagan Kel Zangoye P d a Koulikoro Segou Ta n P c ! Dianka-Daga a ! Rouna ^ ! L ! Dianké Douguel ! Bamako ! ougoundo Leré ! Lac A ! Biro Sikasso Kormou ! Goue ! Sikasso P ! N'Gorkou N'Gouma ! ! ! Horewendou Bia !Sah ! Inadiatafane Koundjoum Simassi ! ! Zoumoultane-N'Gouma ! ! Baraou Kel Tadack M'Bentie ! Kora ! Tiel-Baro ! N'Daba ! ! Ambiri-Habe Bouta ! ! Djo!ndo ! Aoure Faou D O U E N T Z A ! ! ! ! Hanguirde ! Gathi-Loumo ! Oualo Kersani ! Tambeni ! Deri Yogoro ! Handane ! Modioko Dari ! Herao ! Korientzé ! Kanfa Beria G A O Fraction Sormon Youwarou ! Ourou! hama ! ! ! ! ! Guidio-Saré Tiecourare ! Tondibango Kadigui ! Bore-Maures ! Tanal ! Diona Boumbanke Y O U W A R O U ! ! ! ! Kiri Bilanto ! ! Nampala ! Banguita ! bo Sendegué Degue -Dé Hombori Seydou Daka ! o Gamni! d ! la Fraction Sanango a Kikara Na! ki ! ! Ga!na W ! ! Kelma c Go!ui a Te!ye Kadi!oure L ! Kerengo Diambara-Mouda ! Gorol-N! okara Bangou ! ! ! Dogo Gnimignama Sare Kouye ! Gafiti ! ! ! Boré Bossosso ! Ouro-Mamou ! Koby Tioguel ! Kobou Kamarama Da!llah Pringa! -

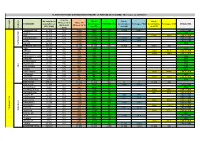

R E GION S C E R C L E COMMUNES No. Total De La Population En 2015

PLANIFICATION DES DISTRIBUTIONS PENDANT LA PERIODE DE SOUDURE - Mise à jour au 26/05/2015 - % du CH No. total de la Nb de Nb de Nb de Phases 3 à 5 Cibles CH COMMUNES population en bénéficiaires TONNAGE CSA bénéficiaires Tonnages PAM bénéficiaires Tonnages CICR MODALITES (Avril-Aout (Phases 3 à 5) 2015 (SAP) du CSA du PAM du CICR CERCLE REGIONS 2015) TOMBOUCTOU 67 032 12% 8 044 8 044 217 10 055 699,8 CSA + PAM ALAFIA 15 844 12% 1 901 1 901 51 CSA BER 23 273 12% 2 793 2 793 76 6 982 387,5 CSA + CICR BOUREM-INALY 14 239 12% 1 709 1 709 46 2 438 169,7 CSA + PAM LAFIA 9 514 12% 1 142 1 142 31 1 427 99,3 CSA + PAM SALAM 26 335 12% 3 160 3 160 85 CSA TOMBOUCTOU TOMBOUCTOU TOTAL 156 237 18 748 18 749 506 13 920 969 6 982 388 DIRE 24 954 10% 2 495 2 495 67 CSA ARHAM 3 459 10% 346 346 9 1 660 92,1 CSA + CICR BINGA 6 276 10% 628 628 17 2 699 149,8 CSA + CICR BOUREM SIDI AMAR 10 497 10% 1 050 1 050 28 CSA DANGHA 15 835 10% 1 584 1 584 43 CSA GARBAKOIRA 6 934 10% 693 693 19 CSA HAIBONGO 17 494 10% 1 749 1 749 47 CSA DIRE KIRCHAMBA 5 055 10% 506 506 14 CSA KONDI 3 744 10% 374 374 10 CSA SAREYAMOU 20 794 10% 2 079 2 079 56 9 149 507,8 CSA + CICR TIENKOUR 8 009 10% 801 801 22 CSA TINDIRMA 7 948 10% 795 795 21 2 782 154,4 CSA + CICR TINGUEREGUIF 3 560 10% 356 356 10 CSA DIRE TOTAL 134 559 13 456 13 456 363 0 0 16 290 904 GOUNDAM 15 444 15% 2 317 9 002 243 3 907 271,9 CSA + PAM ALZOUNOUB 5 493 15% 824 3 202 87 CSA BINTAGOUNGOU 10 200 15% 1 530 5 946 161 4 080 226,4 CSA + CICR ADARMALANE 1 172 15% 176 683 18 469 26,0 CSA + CICR DOUEKIRE 22 203 15% 3 330 -

Preliminary Final Report

DREF: Preliminary Final Report Mali: Ebola virus disease preparedness DREF operation Operation n° MDRML010 Date of Issue: 30 November 2014 Glide n° EP-2014-000039-MLI Date of disaster: N/A Operation start date: 19 April 2014 Operation end date: 31 August 2014 Host National Society: Mali Red Cross Operation budget: CHF 57,715 Number of people affected: Up to 8 million people in at- Number of people assisted: 12,483 risk communities of Bamako, Kayes, Koulikoro and Sikasso; N° of National Societies involved in the operation: IFRC and Mali Red Cross N° of other partner organizations involved in the operation: Ministry of Health A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster In February 2014, there was an outbreak of the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in Guinea, which spread to Liberia, Nigeria, Senegal and Sierra Leone, and most recently Mali, causing untold hardship and hundreds of deaths in these countries. As of 10 November 2014, a total of 14,490 cases, and 5,546 deaths had been recorded, which were attributed to the EVD. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), an outbreak of the EVD was also reported, but is considered of a different origin than that which has affected West Africa. Mali, with a population of 14.8m (UNDP 2012) shares a border with Guinea, which has been especially affected by the EVD, and therefore the risks presented by the epidemic to the country are high. Summary of response Overview of Host National Society On 19 April 2014, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) released CHF 57,715 from the Disaster Relief and Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the Mali Red Cross Society (MRCS) with EVD preparedness activities for a period of three months specifically in the areas of Bamako, Kayes, Koulikoro and Sikasso. -

Dossier Technique Et Financier

DOSSIER TECHNIQUE ET FINANCIER PROJET D’APPUI AUX INVESTISSEMENTS DES COLLECTIVITES TERRITORIALES MALI CODE DGD : 3008494 CODE NAVISION : MLI 09 034 11 TABLE DES MATIÈRES ABRÉVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 4 RÉSUMÉ ....................................................................................................................................... 6 FICHE ANALYTIQUE DE L’INTERVENTION ............................................................................... 8 1 ANALYSE DE LA SITUATION .............................................................................................. 9 1.1 STRATÉGIE NATIONALE .......................................................................................................... 9 1.2 L’IMPACT DE LA CRISE .......................................................................................................... 11 1.3 DISPOSITIF INSTITUTIONNEL DE LA DÉCENTRALISATION ET LES DISPOSITIFS D’APPUI À LA MISE EN ŒUVRE DE LA RÉFORME ................................................................................................................. 12 1.4 L’ANICT ............................................................................................................................ 15 1.5 QUALITÉ DES INVESTISSEMENTS SOUS MAÎTRISE D’OUVRAGE DES CT .................................... 25 1.6 CADRE SECTORIEL DE COORDINATION, DE SUIVI ET DE DIALOGUE ........................................... 29 1.7 CONTEXTE DE -

GROUPE HUMANITAIRE SECURITE ALIMENTAIRE FOOD SECURITY CLUSTER Bamako/Mali ______

GROUPE HUMANITAIRE SECURITE ALIMENTAIRE FOOD SECURITY CLUSTER Bamako/Mali _______________________________________________________________________________________ SitRep / Contribution to OCHA publication 18 Mai 2012 Responses to the food insecurity due to drought and Conflict crisis: WFP is finishing its first round of targeted food distributions in Kayes, Koulikoro and Mopti regions for an estimated 117,800 beneficiaries. The second round is scheduled to start during the week of 21 May, and WFP might distribute a double ration (two months: May and June) to beneficiaries. CRS first round of food distributions through local purchases in fairs began on Saturday, May 10th, 2012 in the commune of Madiama (Circle of Djenne) and will be extended in other communes of this circle. As of today 3 153 households have received two months food rations (equivalent to $100 per household). Diverse products are been proposed. A total of 140 000 000 FCFA has been invested in that local purchases. Mrs Aminata Sow, Head of Family in Welinngara village received her foods during the ongoing fair in Djenne Logistic support: The second joint mission WFP/UNDSS/OCHA in Mopti will provide further information on the UN common center and logistics hub establishment. North Mali: The WFP commodities on the High Islamic Council convoy have arrived in the three northern cities of Timbuktu, Gao and Kidal. WFP dispatched a total of 31,5mt of mixed commodities (pulses and vegetable oil) to the three regions. This tonnage of mixed WFP commodities complements cereal distributions of the High Islamic Council for provision of a complete food basket to an estimated 7,800 vulnerable conflict-affected people in the North. -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à