Personal and Political Networks in 1917: Vladimir Zenzinov and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boris Kolonitskii, “'Democracy' in the Political Consciousness of The

"Democracy" in the Political Consciousness of the February Revolution Author(s): Boris Ivanovich Kolonitskii Source: Slavic Review, Vol. 57, No. 1 (Spring, 1998), pp. 95-106 Published by: Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2502054 . Accessed: 17/09/2013 09:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Slavic Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.197.27.9 on Tue, 17 Sep 2013 09:58:33 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions "Democracy" in the Political Consciousness of the FebruaryRevolution Boris Ivanovich Kolonitskii Historians of quite diverging orientations have interpreted the Feb- ruary revolution of 1917 in Russia as a "democratic" revolution. Sev- eral generations of Marxists of various stripes (tolk) have called it a "bourgeois-democratic revolution." In the years of perestroika, the contrast between democratic February and Bolshevik October became an important part of the historical argument of the anticommunist movement. The February revolution was regarded as a dramatic, un- successful attempt at the modernization and westernization of Russia, as its democratization. -

The Azef Affair and Late Imperial Russian Modernity

Chto Takoe Azefshchina?: The Azef Affair and Late Imperial Russian Modernity By Jason Morton Summer 2011 Jason Morton is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History at the University of California, Berkeley. “Petersburg streets possess one indubitable quality: they transform passersby into shadows.” -Andrei Bely “Now when even was come, he sat down with the twelve. And as they did eat, he said, Verily I say unto you, that one of you shall betray me. And they were exceedingly sorrowful, and began every one of them to say unto him, Lord, is it I? And he answered and said, He that dippeth his hand with me in the dish, the same shall betray me.” -Matthew 26: 20-23 Introduction: Azefshchina- What’s in a name? On January 18, 1909 (O.S.) the former Russian chief of police, A.A. Lopukhin, was arrested and his house was searched. Eleven packages containing letters and documents were sealed up and taken away. 1 Lopukhin stood accused of confirming to representatives of the Socialist Revolutionary Party that one of their oldest and most respected leaders, Evno Azef, had been a government agent working for the secret police (Okhrana) since 1893. The Socialist Revolutionaries (or SRs) were a notorious radical party that advocated the overthrow of the Russian autocracy by any means necessary.2 The Combat Organization (Boevaia Organizatsiia or B.O.) of the SR Party was specifically tasked with conducting acts of revolutionary terror against the government and, since January of 1904, Evno Azef had been the head of this Combat Organization.3 This made him the government’s most highly placed secret agent in a revolutionary organization. -

Who Were the “Greens”? Rumor and Collective Identity in the Russian Civil War

Who Were the “Greens”? Rumor and Collective Identity in the Russian Civil War ERIK C. LANDIS In the volost center of Kostino-Otdelets, located near the southern border of Borisoglebsk uezd in Tambov province, there occurred what was identified as a “deserters’ revolt” in May 1919. While no one was killed, a group of known deserters from the local community raided the offices of the volost soviet, destroying many documents relating to the previous months’ attempts at military conscription, and stealing the small number of firearms and rubles held by the soviet administration and the volost Communist party cell. The provincial revolutionary tribunal investigated the affair soon after the events, for while there was an obvious threat of violence, no such escalation occurred, and the affair was left to civilian institutions to handle. The chairman of the volost soviet, A. M. Lysikov, began his account of the event on May 18, when he met with members of the community following a morning church service in order to explain the recent decrees and directives of the provincial and central governments.1 In the course of this discussion, he raised the fact that the Council of Workers’ and Peasants’ Defense in Moscow had declared a seven-day amnesty for all those young men who had failed to appear for mobilization to the Red Army, particularly those who had been born in 1892 and 1893, and had been subject to the most recent age-group mobilization.2 It was at this moment that one of the young men in the village approached him to ask if it was possible to ring the church bell and call for an open meeting of deserters in the volost, at which they could collectively agree whether to appear for mobilization. -

Sidney Reilly's Reports from South Russia, December 1918-March 1919

Ainsworth, J. (1998) Sidney Reilly's reports from South Russia, December 1918-March 1919. Europe-Asia Studies. 50(8) 1447-1470 COPYRIGHT 1998 Carfax Publishing Company Sidney Reilly's reports from South Russia, December 1918-March 1919. John Ainsworth Sidney Reilly has become a legendary figure as the master spy of the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). 'He was surely not only the master spy of this century', wrote one ardent admirer, 'but of all time'. While his activities as an intelligence agent in British service have only been glimpsed through the veil of secrecy that officialdom invariably imposes on such matters, nonetheless, they seem to have an aura of the extraordinary about them. Supposedly they even surpassed the amazing exploits of the fictional super-spy character James Bond, whose creator Ian Fleming, himself a former officer of the Naval Intelligence Directorate, declared: 'James Bond is just a piece of nonsense I dreamed up. He's not a Sidney Reilly, you know!'(1) Other estimates of his achievements have been rather less flattering though. Some senior officials of the Foreign Office in London, for instance, were said to have dismissed the Reilly legend as one derived largely from his inclination to 'exaggerate his own importance', while an acclaimed historical study of Britain's secret intelligence agencies described Reilly's secret service career overall as 'remarkable, though largely ineffective ...'.(2) Examination of his reports from South Russia, and their manner of compilation as well, affords us a unique opportunity to assess both his function and performance, at least on this particular occasion, as an agent in the field for MI6. -

The Socialist Revolutionary Party

onmicrofilm The SocialistRevolutionary Party Archive collection of the PartiiaSocialistov-Revoliutsionerov 5EIVIA5HBOAM fi1iROP1361.1 oliPtT 'EMI) Tbm Pth0CBO E 11APT151- CORIAA VICTOR% PEBOAKRIOHEPOITh International Institute of Social History (IISH) IDC The Socialist Revolutionary Party The archives of the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR) are now for the first time available in convenient, fully-indexed microfilm format from IDC Publishers. This collection, held by the International Institute of Social History (IISH), Amsterdam, contains minutes of party congresses and documents of local party organizations in Russia and Western Europe, original correspondence, leaflets and proclamations, documents of and about Socialist International, Russian Ochranka and many other organizations. This microform collection is without any doubt anindispensable research tool in the field of social history and Slavic studies. History of the Socialist Revolutionary Moscow and brother-in-law of Tsar Karlsruhe. Upon returning to Russia in Party Nicolas H. Meanwhile,a left-wing 1899 he moved in circles connected Partiia Socialistov-Revoliutsionerov (in spin-off, the Maximalists, pursued a with the birth of the SR in 1901. When Russian, abbreviated to ceserys) terrorist campaign against the state even Gershuni, a principal advocate of occupies a special place in Russian more intense than that of the SR. In terrorism within the SR was arrested for history. Together with that of the 1905 the main party advocated the the murder of Minister Sipiagin in 1902, Mensheviks and the anarchists, this formation of a Constituent Assembly Azev became the head of the party's history belongs to the victims to the left and supported universal suffrage. Combat organization. He was a prime of the Bolsheviks. -

Arkhangel'sk, 1918: Regionalism and Populism in the Russian Civil War Author(S): Yanni Kotsonis Source: Russian Review, Vol

The Editors and Board of Trustees of the Russian Review Arkhangel'sk, 1918: Regionalism and Populism in the Russian Civil War Author(s): Yanni Kotsonis Source: Russian Review, Vol. 51, No. 4 (Oct., 1992), pp. 526-544 Published by: Wiley on behalf of The Editors and Board of Trustees of the Russian Review Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/131044 . Accessed: 15/11/2013 01:18 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley and The Editors and Board of Trustees of the Russian Review are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Russian Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.197.26.12 on Fri, 15 Nov 2013 01:18:00 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Arkhangel'sk,1918: Regionalismand Populism in the Russian Civil War YANNI KOTSONIS In August 1918 a group of moderate socialists, liberals, and army officers over- threw the Bolshevik authorities of Arkhangel'sk province and replaced them with the Supreme Administration of the Northern Region (Verkhovnoe Upravlenie Severnoi Oblasti). The new authorities intended the North to serve as a foothold from which to remove the Bolsheviks from power in the remainder of Russia. -

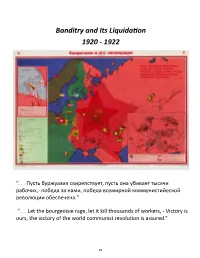

Map 10 Banditry and Its Liquidation // 1920 - 1922 Colored Lithographic Print, 64 X 102 Cm

Banditry and Its Liquidation 1920 - 1922 “. Пусть буржуазия свирепствует, пусть она убивает тысячи рабочих,- победа за нами, победа всемирной коммунистийеской революции обеспечена.” “. Let the bourgeoisie rage, let it kill thousands of workers, - Victory is ours, the victory of the world communist revolution is assured.” 62 Map 10 Banditry and Its Liquidation // 1920 - 1922 Colored Lithographic print, 64 x 102 cm. Compilers: A. N. de-Lazari and N. N. Lesevitskii Artist: S. R. Zelikhman Historical Background and Thematic Design The Russian Civil War did not necessarily end with the defeat of the Whites. Its final stage involved various independent bands of partisans and rebels that took advantage of the chaos enveloping the country and contin- ued to operate in rural areas of Ukraine, Tambov Province, the lower Volga, and western Siberia, where Bol- shevik authority was more or less tenuous. Their leaders were by and large experienced military men who stoked peasant hatred for centralized authority, whether it was German occupation forces, Poles, Moscow Bol- sheviks, or Jews. They squared off against the growing power of the communists, which is illustrated as series of five red stars extending over all four sectors. The red circle identifies Moscow as the seat of Soviet power, while the five red stars, enlarging in size but diminishing in color intensity as they move further from Moscow, represent the increasing strength of Communism in Russia during the years 1920-22. The stars also serve as symbolic shields, apparently deterring attacking forces that emanate from Poland, Ukraine, and the Volga region. The red flag with the gold emblem of the hammer-and-sickle in the upper hoist quarter, and the letters Р. -

Evil Men Have No Songs: the Terrorist and Literatuer Boris Savinkov, 1879-1925

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2016 Evil Men Have No Songs: The eT rrorist and Literatuer Boris Savinkov, 1879-1925 Irina Vasilyeva Meier University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Meier, I. V.(2016). Evil Men Have No Songs: The Terrorist and Literatuer Boris Savinkov, 1879-1925. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3565 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVIL MEN HAVE NO SONGS: THE TERRORIST AND LITTÉRATUER BORIS SAVINKOV, 1879-1925 by Irina Vasilyeva Meier Bachelor of Science Eastern New Mexico University, 2008 Master of Arts Eastern New Mexico University, 2010 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Judith Kalb, Major Professor Alexander Ogden, Committee Member Alexander Beecroft, Committee Member John Muckelbauer, Committee Member Elena Osokina, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Irina Vasilyeva Meier, 2016 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Back in the ninth grade I took an interest in a new book on the family bookshelf, because I recognized the author’s name from my Russian history class. The book was called Vospominaniia terrorista (The Memoirs of a Terrorist) by Boris Savinkov. -

Memory Politics in Contemporary Russia

Memory Politics in Contemporary Russia This book examines the societal dynamics of memory politics in Russia. Since Vladimir Putin became president, the Russian central government has increas- ingly actively employed cultural memory to claim political legitimacy and dis- credit all forms of political opposition. The rhetorical use of the past has become adefining characteristic of Russian politics, creating a historical foundation for the regime’s emphasis on a strong state and centralised leadership. Exploring memory politics, this book analyses a wide range of actors, from the central government and the Russian Orthodox Church to filmmaker and cultural heavyweight Nikita Mikhalkov and radical thinkers such as Alek- sandr Dugin. In addition, in view of the steady decline in media freedom since 2000, it critically examines the role of cinema and television in shaping and spreading these narratives. Thus, this book aims to promote a better understanding of the various means through which the Russian government practices its memory politics (e.g. the role of state media) while at the same time pointing to the existence of alternative and critical voices and criticism that existing studies tend to overlook. Contributing to current debates in the field of memory studies and of cur- rent affairs in Russia and Eastern Europe, this book will be of interest to scholars working in the fields of Russian studies, cultural memory studies, nationalism and national identity, political communication, film, television and media studies. Mariëlle Wijermars is a postdoctoral researcher at the Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki. Studies in Contemporary Russia Series Editor: Markku Kivinen Studies in Contemporary Russia is a series of cutting-edge, contemporary studies. -

Sidney Reilly's Reports from South Russia, December 1918-March 1919

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queensland University of Technology ePrints Archive Ainsworth, J. (1998) Sidney Reilly's reports from South Russia, December 1918-March 1919. Europe-Asia Studies. 50(8) 1447-1470 COPYRIGHT 1998 Carfax Publishing Company Sidney Reilly's reports from South Russia, December 1918-March 1919. John Ainsworth Sidney Reilly has become a legendary figure as the master spy of the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). 'He was surely not only the master spy of this century', wrote one ardent admirer, 'but of all time'. While his activities as an intelligence agent in British service have only been glimpsed through the veil of secrecy that officialdom invariably imposes on such matters, nonetheless, they seem to have an aura of the extraordinary about them. Supposedly they even surpassed the amazing exploits of the fictional super-spy character James Bond, whose creator Ian Fleming, himself a former officer of the Naval Intelligence Directorate, declared: 'James Bond is just a piece of nonsense I dreamed up. He's not a Sidney Reilly, you know!'(1) Other estimates of his achievements have been rather less flattering though. Some senior officials of the Foreign Office in London, for instance, were said to have dismissed the Reilly legend as one derived largely from his inclination to 'exaggerate his own importance', while an acclaimed historical study of Britain's secret intelligence agencies described Reilly's secret service career overall as 'remarkable, though largely ineffective ...'.(2) Examination of his reports from South Russia, and their manner of compilation as well, affords us a unique opportunity to assess both his function and performance, at least on this particular occasion, as an agent in the field for MI6. -

The GREAT CONSPIRACY Against RUSSIA

“AN EXTRAORDINARY BOOK” — Joseph E. Davies FORMER AMBASSADOR TO THE SOVIET UNION The GREAT CONSPIRACY against RUSSIA by MICHAEL SAYERS AND ALBERT E. KAHN AUTHORS OF SABOTAGE Special Introduction by Senator Claude Pepper NEW COMPLETE AND UNABRIDGED EDITION ABOUT THE AUTHORS The authors of this book, Michael Sayers and Albert E. Kahn, have won an international reputation for their investigations of se- cret diplomacy and fifth column operations; For a number of years Mr. Sayers specialized in investigating and writing about Axis fifth column intrigue; and the first compre- hensive exposes of Nazi conspiracy in France, England and Ireland to be published in the United States were written by Mr. Sayers. Mr. Sayers is also well known as a short story writer, and Edward J. O’Brien dedicated one of his famous anthologies to him. Albert E. Kahn was formerly the Executive Secretary of the American Council Against Nazi Propaganda, of which the late Wil- liam E. Dodd, former Ambassador to Germany, was Chairman. As editor of The Hour, a confidential newsletter devoted to exposing Axis fifth column operations, Mr. Kahn became widely known for his exclusive news scoops on German and Japanese conspiratorial activities in the Americas. The first book on which Mr. Sayers and Mr. Kahn collaborated, Sabotage! The Secret War Against America, was one of the out- standing best-sellers of the war period. Their second book, The Plot Against the Peace achieved top sales in the early months of the postwar period. Their current work, The Great Conspiracy Against Russia, was first published early in February, 1946. -

Russian Nationalism

Russian Nationalism This book, by one of the foremost authorities on the subject, explores the complex nature of Russian nationalism. It examines nationalism as a multi layered and multifaceted repertoire displayed by a myriad of actors. It considers nationalism as various concepts and ideas emphasizing Russia’s distinctive national character, based on the country’s geography, history, Orthodoxy, and Soviet technological advances. It analyzes the ideologies of Russia’s ultra nationalist and far-right groups, explores the use of nationalism in the conflict with Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea, and discusses how Putin’s political opponents, including Alexei Navalny, make use of nationalism. Overall the book provides a rich analysis of a key force which is profoundly affecting political and societal developments both inside Russia and beyond. Marlene Laruelle is a Research Professor of International Affairs at the George Washington University, Washington, DC. BASEES/Routledge Series on Russian and East European Studies Series editors: Judith Pallot (President of BASEES and Chair) University of Oxford Richard Connolly University of Birmingham Birgit Beumers University of Aberystwyth Andrew Wilson School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London Matt Rendle University of Exeter This series is published on behalf of BASEES (the British Association for Sla vonic and East European Studies). The series comprises original, high quality, research level work by both new and established scholars on all aspects of Russian,