Beyond Jamestown: Virginia Indians Today and Yesterday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

Bladensburg Prehistoric Background

Environmental Background and Native American Context for Bladensburg and the Anacostia River Carol A. Ebright (April 2011) Environmental Setting Bladensburg lies along the east bank of the Anacostia River at the confluence of the Northeast Branch and Northwest Branch of this stream. Formerly known as the East Branch of the Potomac River, the Anacostia River is the northernmost tidal tributary of the Potomac River. The Anacostia River has incised a pronounced valley into the Glen Burnie Rolling Uplands, within the embayed section of the Western Shore Coastal Plain physiographic province (Reger and Cleaves 2008). Quaternary and Tertiary stream terraces, and adjoining uplands provided well drained living surfaces for humans during prehistoric and historic times. The uplands rise as much as 300 feet above the water. The Anacostia River drainage system flows southwestward, roughly parallel to the Fall Line, entering the Potomac River on the east side of Washington, within the District of Columbia boundaries (Figure 1). Thin Coastal Plain strata meet the Piedmont bedrock at the Fall Line, approximately at Rock Creek in the District of Columbia, but thicken to more than 1,000 feet on the east side of the Anacostia River (Froelich and Hack 1975). Terraces of Quaternary age are well-developed in the Bladensburg vicinity (Glaser 2003), occurring under Kenilworth Avenue and Baltimore Avenue. The main stem of the Anacostia River lies in the Coastal Plain, but its Northwest Branch headwaters penetrate the inter-fingered boundary of the Piedmont province, and provided ready access to the lithic resources of the heavily metamorphosed interior foothills to the west. -

James River Geography

James River Geography Welcome to NOAA's James River Interpretive Buoy, located at latitude 37 degrees 12.25 minutes North, longitude 76 degrees 46.65 minutes West. It lies off Jamestown Island about a quarter-mile south of Captain John Smith's statue, where he can see it well as he looks out over the river. This buoy is anchored in 43 feet of water at the edge of the narrow shoal that runs along the island. The river's channel is deep here, as the James narrows down between Swanns Point on the south and Jamestown on the north, but it quickly shoals as it sweeps through the broad meander curve from Cobham Bay around Hog Island and down toward Burwell Bay. The buoy lies about thirty miles above the mouth of the James at Hampton Roads. Jamestown Island lies at a transition point on the James. Five miles upstream is the mouth of the Chickahominy River, which adds a strong current of fresh water to the heavy flow already coming out of the James watershed from deep in Virginia's uplands, the mountains at the eastern edge of the Alleghany Plateau. In wet years, the water here is nearly fresh. The mouth of the James, however, lies close to the Chesapeake's mouth, so salt water can also flow upriver with the tides. In John Smith's time here, the region suffered a multi-year drought, so the river and the colonists' drinking water was probably brackish, an irritating factor that may account for some of the bickering and poor health that plagued them. -

Proposed Finding

This page is intentionally left blank. Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) Proposed Finding Proposed Finding The Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 Regulatory Procedures .............................................................................................1 Administrative History.............................................................................................2 The Historical Indian Tribe ......................................................................................4 CONCLUSIONS UNDER THE CRITERIA (25 CFR 83.7) ..............................................9 Criterion 83.7(a) .....................................................................................................11 Criterion 83.7(b) ....................................................................................................21 Criterion 83.7(c) .....................................................................................................57 Criterion 83.7(d) ...................................................................................................81 Criterion 83.7(e) ....................................................................................................87 Criterion 83.7(f) ...................................................................................................107 -

The Lincoln- Mcclellan Relationship in Myth and Memory

The Lincoln- McClellan Relationship in Myth and Memory MARK GRIMSLEY Like many Civil War historians, I have for many years accepted invita- tions to address the general public. I have nearly always tried to offer fresh perspectives, and these have generally been well received. But almost invariably the Q and A or personal exchanges reveal an affec- tion for familiar stories or questions. (Prominent among them is the query “What if Stonewall Jackson had been present at Gettysburg?”) For a long time I harbored a private condescension about this affec- tion, coupled with complete incuriosity about what its significance might be. But eventually I came to believe that I was missing some- thing important: that these familiar stories, endlessly retold in nearly the same ways, were expressions of a mythic view of the Civil War, what the amateur historian Otto Eisenschiml memorably labeled “the American Iliad.”1 For Eisenschiml “the American Iliad” was merely a clever title for a compendium of eyewitness accounts of the conflict, but I take the term seriously. In Homer’s Iliad the anger of Achilles, the perfidy of Agamemnon, the doomed gallantry of Hector—and the relationships between them—have enormous, uncontested, unchanging, and almost primal symbolic meaning. So too do certain figures in the American Iliad. Prominent among these are the butcher Grant, the Christ-like Lee, and the rage- filled Sherman. I believe that the traditional Civil War narrative functions as a national myth of central importance to our understanding of ourselves as Americans. And like the classic mythologies of old, it contains timeless wisdom about what it means to be a human being. -

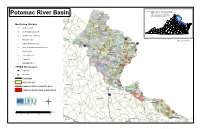

Potomac River Basin Assessment Overview

Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality PL01 Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Potomac River Basin Virginia Geographic Information Network PL03 PL04 United States Geological Survey PL05 Winchester PL02 Monitoring Stations PL12 Clarke PL16 Ambient (120) Frederick Loudoun PL15 PL11 PL20 Ambient/Biological (60) PL19 PL14 PL23 PL08 PL21 Ambient/Fish Tissue (4) PL10 PL18 PL17 *# 495 Biological (20) Warren PL07 PL13 PL22 ¨¦§ PL09 PL24 draft; clb 060320 PL06 PL42 Falls ChurchArlington jk Citizen Monitoring (35) PL45 395 PL25 ¨¦§ 66 k ¨¦§ PL43 Other Non-Agency Monitoring (14) PL31 PL30 PL26 Alexandria PL44 PL46 WX Federal (23) PL32 Manassas Park Fairfax PL35 PL34 Manassas PL29 PL27 PL28 Fish Tissue (15) Fauquier PL47 PL33 PL41 ^ Trend (47) Rappahannock PL36 Prince William PL48 PL38 ! PL49 A VDH-BEACH (1) PL40 PL37 PL51 PL50 VPDES Dischargers PL52 PL39 @A PL53 Industrial PL55 PL56 @A Municipal Culpeper PL54 PL57 Interstate PL59 Stafford PL58 Watersheds PL63 Madison PL60 Impaired Rivers and Streams PL62 PL61 Fredericksburg PL64 Impaired Reservoirs or Estuaries King George PL65 Orange 95 ¨¦§ PL66 Spotsylvania PL67 PL74 PL69 Westmoreland PL70 « Albemarle PL68 Caroline PL71 Miles Louisa Essex 0 5 10 20 30 Richmond PL72 PL73 Northumberland Hanover King and Queen Fluvanna Goochland King William Frederick Clarke Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Loudoun Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Rappahannock River Basin -

EPA Interim Evaluation of Virginia's 2016-2017 Milestones

Interim Evaluation of Virginia’s 2016-2017 Milestones Progress June 30, 2017 EPA INTERIM EVALUATION OF VIRGINIA’s 2016-2017 MILESTONES As part of its role in the accountability framework, described in the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (Bay TMDL) for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is providing this interim evaluation of Virginia’s progress toward meeting its statewide and sector-specific two-year milestones for the 2016-2017 milestone period. In 2018, EPA will evaluate whether each Bay jurisdiction achieved the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) partnership goal of practices in place by 2017 that would achieve 60 percent of the nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment reductions necessary to achieve applicable water quality standards in the Bay compared to 2009. Load Reduction Review When evaluating 2016-2017 milestone implementation, EPA is comparing progress to expected pollutant reduction targets to assess whether statewide and sector load reductions are on track to have practices in place by 2017 that will achieve 60 percent of necessary reductions compared to 2009. This is important to understand sector progress as jurisdictions develop the Phase III Watershed Implementation Plans (WIP). Loads in this evaluation are simulated using version 5.3.2 of the CBP partnership Watershed Model and wastewater discharge data reported by the Bay jurisdictions. According to the data provided by Virginia for the 2016 progress run, Virginia is on track to achieve its statewide 2017 targets for nitrogen and phosphorus but is off track to meet its statewide targets for sediment. The data also show that, at the sector scale, Virginia is off track to meet its 2017 targets for nitrogen reductions in the Agriculture, Urban/Suburban Stormwater and Septic sectors and is also off track for phosphorus in the Urban/Suburban Stormwater sector, and off track for sediment in the Agriculture and Urban/Suburban Stormwater sectors. -

Living with the Indians.Rtf

Living With the Indians Introduction Archaeologists believe the American Indians were the first people to arrive in North America, perhaps having migrated from Asia more than 16,000 years ago. During this Paleo time period, these Indians rapidly spread throughout America and were the first people to live in Virginia. During the Woodland period, which began around 1200 B.C., Indian culture reached its highest level of complexity. By the late 16th century, Indian people in Coastal Plain Virginia, united under the leadership of Wahunsonacock, had organized themselves into approximately 32 tribes. Wahunsonacock was the paramount or supreme chief, having held the title “Powhatan.” Not a personal name, the Powhatan title was used by English settlers to identify both the leader of the tribes and the people of the paramount chiefdom he ruled. Although the Powhatan people lived in separate towns and tribes, each led by its own chief, their language, social structure, religious beliefs and cultural traditions were shared. By the time the first English settlers set foot in “Tsenacommacah, or “densely inhabited land,” the Powhatan Indians had developed a complex culture with a centralized political system. Living With the Indians is a story of the Powhatan people who lived in early 17th-century Virginia—their social, political, economic structures and everyday life ways. It is the story of individuals, cultural interactions, events and consequences that frequently challenged the survival of the Powhatan people. It is the story of how a unique culture, through strong kinship networks and tradition, has endured and maintained tribal identities in Virginia right up to the present day. -

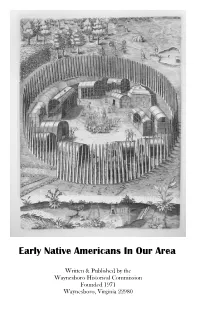

Native Americans in Our Area

Early Native Americans In Our Area Written & Published by the Waynesboro Historical Commission Founded 1971 Waynesboro, Virginia 22980 Dedication The Historic Commission of Waynesboro dedicates this publication to the earliest settlers of the North American Continent and in particular Virginia and our immediate region. Their relentless push through an unmarked environment exemplifies the quest of the human spirit to reach the horizon and make it its own. Until relatively recently, a history of America would devote a slight section to the Indian tribes discovered by the colonists who landed on the North American continent. The subsequent text would detail the claiming of the land, the creation of towns and villages, and the conquering of the forces that would halt the relentless move to the West. That view of history has been challenged by the work of archeologists who have used the advances in science and the skills of excavation to reveal a past that had been forgotten or deliberatively ignored. This publication seeks to present a concise chronicle of the prehistory of our country and our region with attention to one of the forgotten and marginalized civilizations, the Monacans who existed and prospered in Central Virginia and the areas immediate to Waynesboro. Migration to North America Well before the Romans, the Greeks, or the Egyptians created the culture we call Western Civilization, an ethnic group known as the “First People” began its colonization of the North American continent. There are a number of theories of how the original settlers came to the continent. Some thought they were the “Lost Tribes” of the Old Testament. -

Chapter 3 USFWS Great Spangled Fritillary

Chapter 3 USFWS Great spangled fritillary Existing Environment ■ Introduction ■ The Physical Landscape ■ The Cultural Landscape Setting and Land Use History ■ Current Climate ■ Air Quality ■ Water Quality ■ Regional Socio-Economic Setting ■ Refuge Administration ■ Special Use Permits, including Research ■ Refuge Natural Resources ■ Refuge Biological Resources ■ Refuge Visitor Services Program ■ Archealogical and Historical Resources The Physical Landscape Introduction This chapter describes the physical, biological, and social environment of the Rappahannock River Valley refuge. We provide descriptions of the physical landscape, the regional setting and its history, and the refuge setting, including its history, current administration, programs, and specifi c refuge resources. Much of what we describe below refl ects the refuge environment as it was in 2007. Since that time, we have been writing, compiling and reviewing this document. As such, some minor changes likely occurred to local conditions or refuge programs as we continued to implement under current management. However, we do not believe those changes appreciably affect what we present below. The Physical Landscape Watershed Our project area is part of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, a drainage basin of 64,000 square miles encompassing parts of the states of Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia. The waters of that basin fl ow into the Chesapeake Bay, the nation’s largest estuary. The watershed contains an array of habitat types, including mixed hardwood forests typical of the Appalachian Mountains, grasslands and agricultural fi elds, lakes, rivers, and streams, wetlands and shallow waters, and open water in tidal rivers and the estuary. That diversity supports more than 2,700 species of plants and animals, including Service trust resources such as endangered or threatened species, migratory birds, and anadromous fi sh (www.fws.gov/chesapeakebay/ coastpgm.htm). -

Pocahontas and Captain John Smith Revisited

Pocahontas and Captain John Smith Revisited FREDERIC W. GLEACH Cornell University The story of Pocahontas and Captain John Smith is one that all school children in the United States seem to learn early on, and one that has served as the basis for plays, epic poems, and romance novels as well as historical studies. The lyrics of Peggy Lee's hit song Fever exemplify these popular treatments: Captain Smith and Pocahontas Had a very mad affair. When her daddy tried to kill him She said, 'Daddy, oh don't you dare — He gives me fever ... with his kisses, Fever when he holds me tight; Fever — I'm his Mrs. Daddy won't you treat him right.' (Lee et al 1958) The incident referred to here, Pocahontas's rescue of Smith from death at the orders of her father, the paramount chief Powhatan, was originally recorded by the only European present — Smith himself. While the factu- ality of Smith's account has been questioned since the mid-19th century, recent textual analysis by Lemay (1992) supports the more widely held opinion that it most likely occurred as Smith reported. Other recent studies have employed methods and models imported from literary criticism, gen erally to demonstrate the nature of English colonial and historical modes of apprehending otherness.1 While my work may be easily contrasted to these approaches, two re cent studies must be mentioned which have employed understandings and methods similar to my own. Kidwell (1992:99-101) used Pocahontas as an example in her discussion of "Indian Women as Cultural Mediators", 1ln addition to the comments of participants in the Algonquian Conference I have had the benefit of discussion with members of the Department of Anthropol ogy of Cornell University, where I presented some of these ideas in a departmental colloquium. -

The Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial Sara J

The Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial Sara J. Schechner (Cambridge MA) Let me tell you a tale of intrigue and ingenuity, savagery and foreign shores, sex and scientific instruments. No, it is not “Desperate Housewives,” or “CSI,” but the “Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial.”1 As our story opens in 1607, we find Captain John Smith paddling upstream through the Virginia wilderness, when he is ambushed by Indians, held prisoner, and repeatedly threatened with death. His life is spared first by the intervention of his magnetic compass, whose spinning needle fascinates his captors, and then by Pocahontas, the chief’s sexy daughter. At least that is how recent movies and popular writing tell the story.2 But in fact the most famous compass in American history was more than a compass – it was a pocket sundial – and the Indian princess was no seductress, but a mere child of nine or ten years, playing her part in a shaming ritual. So let us look again at the legend, as told by John Smith himself, in order to understand what his instrument meant to him. Who was John Smith?3 When Smith (1580-1631) arrived on American shores at the age of twenty-seven, he was a seasoned adventurer who had served Lord Willoughby in Europe, had sailed the Mediterranean in a merchant vessel, and had fought for the Dutch against Spain and the Austrians against the Turks. In Transylvania, he had been captured and sold as a slave to a Turk. The Turk had sent Smith as a gift to his girlfriend in Istanbul, but Smith escaped and fled through Russia and Poland.