1 Historical Performance in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759)

Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759) Sämtliche Werke / Complete works in MP3-Format Details Georg Friedrich Händel (George Frederic Handel) (1685-1759) - Complete works / Sämtliche Werke - Total time / Gesamtspielzeit 249:50:54 ( 10 d 10 h ) Titel/Title Zeit/Time 1. Opera HWV 1 - 45, A11, A13, A14 116:30:55 HWV 01 Almira 3:44:50 1994: Fiori musicali - Andrew Lawrence-King, Organ/Harpsichord/Harp - Beate Röllecke Ann Monoyios (Soprano) - Almira, Patricia Rozario (Soprano) - Edilia, Linda Gerrard (Soprano) - Bellante, David Thomas (Bass) - Consalvo, Jamie MacDougall (Tenor) - Fernando, Olaf Haye (Bass) - Raymondo, Christian Elsner (Tenor) - Tabarco HWV 06 Agrippina 3:24:33 2010: Akademie f. Alte Musik Berlin - René Jacobs Alexandrina Pendatchanska (Soprano) - Agrippina, Jennifer Rivera (Mezzo-Soprano) - Nerone, Sunhae Im (Soprano) - Poppea, Bejun Mehta (Counter-Tenor) - Ottone, Marcos Fink (Bass-Bariton) - Claudio, Neal Davis (Bass-Bariton) - Pallante, Dominique Visse (Counter-Tenor) - Narciso, Daniel Schmutzhard (Bass) - Lesbo HWV 07 Rinaldo 2:54:46 1999: The Academy of Ancient Music - Christopher Hogwood Bernarda Fink (Mezzo-Sopran) - Goffredo, Cecilia Bartoli (Mezzo-Sopran) - Almirena, David Daniels (Counter-Tenor) - Rinaldo, Daniel Taylor (Counter-Tenor) - Eustazio, Gerald Finley (Bariton) - Argante, Luba Orgonasova (Soprano) - Armida, Bejun Mehta (Counter-Tenor) - Mago cristiano, Ana-Maria Rincón (Soprano) - Donna, Sirena II, Catherine Bott (Soprano) - Sirena I, Mark Padmore (Tenor) - Un Araldo HWV 08c Il Pastor fido 2:27:42 1994: Capella -

Orquestra Barroca

8 Jan 2017 Orquestra 18:00 Sala Suggia – CICLO BARROCO BPI Barroca ANO BRITÂNICO Casa da Música Rachel Podger violino e direcção musical 1ª PARTE 2ª PARTE George Frideric Handel Jan Dismas Zelenka Concerto Grosso em Si bemol maior, Hipocondrie a 7 Concertanti (1723; c.8min) op. 3 n.º 2 (c.1715-18; c.12min) 1. [Grave] – 1. Vivace 2. Allegro – 2. Largo 3. Lentement 3. Allegro 4. Menuet Johann Sebastian Bach 5. Gavotte Concerto para violino em Lá menor, BWV 1041 (c.1717-23; c.14min) Antonio Vivaldi 1. [Allegro] Concerto para violino em Dó menor, 2. Andante op. 9 n.º 11 (1727; c.10min) 3. Allegro assai 1. Allegro 2. Adagio Antonio Vivaldi 3. Allegro Concerto para violino em Ré maior, op. 4 n.º 11 (c.1715; c.6min) Henry Purcell 1. Allegro Música de cena de Fairy Queen 2. Largo e King Arthur (1691-92; c.14min) 3. Allegro assai 1. Prelude 2. Hornpipe 3. Rondeau 4. Prelude (Act V): If love’s a sweet passion 5. Dance for the Fairies 6. Jig 7. Fairest Isle – Air 8. Chaconne: Dance for the Chinese man and woman Grandes Concertos para Violino APOIO CICLO GRANDES CONCERTOS PARA VIOLINO PATROCINADORES ANO BRITÂNICO APOIO ANO BRITÂNICO A CASA DA MÚSICA É MEMBRO DE Nesta tradição inserem-se os 6 Concerti “Concerto” ou “stile concertato” ainda são, no Grossi, op. 3 de George Frideric Handel (Halle, início do Barroco, termos fluidos que, de diver- 1686 – Londres, 1759), publicados em 1734 em sas maneiras, parecem aludir ao gosto pela Londres por John Walsh; o editor juntou, prova- mistura dos vários elementos sonoros dentro velmente sem a autorização de Handel, algu- de uma composição, gosto que marca a supe- mas composições já escritas há algum tempo, ração progressiva do ideal de harmonia e da a fim de aproveitar, com um trabalho que o tendência para a homogeneidade que havia evocava explicitamente no título, o sucesso caracterizado a arte renascentista. -

Antonio Vivaldi’S Reputation As a ComPoser Contemporaries

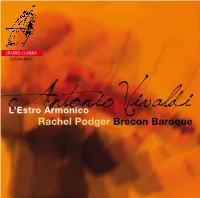

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 36515 L’Estro Armonico AntonioRachel Podger Brecon Vivaldi Baroque 1 Rachel Podger Music, The European Union Baroque Baroque violin/director Orchestra, Holland Baroque Society and the Handel and Haydn Society (USA). 2012 Rachel Podger is one of the most creative saw Rachel guest directing twice in Canada, talents to emerge in the field of period per with Arion (Montreal) and Tafelmusik formance. Over the last two decades she (Toronto) and curate a Bach festival in Tokyo. has established herself as a leading inter 2014 included collaborations with The preter English Concert, Camerata Bern, a BBC of the music of the Baroque and Classical Chamber Prom and concerts at Wigmore periods and holds numerous awardwinning Hall and the new Sam Wanamaker recordings to her name ranging from early Playhouse at Shakespeare’s Globe theatre. seventeenth century music to Mozart and Rachel records exclusively for Channel Haydn. She was educated in Germany and Classics and has won numerous presti gious in England at the Guildhall School of Music awards, including Diapasons d’Or and a and Drama, where she studied with David Baroque Instrumental Gramophone Award Takeno and Micaela Comberti. for La Stravaganza in 2003. In 2012 Rachel After beginnings with The Palladian won the Diapason d’Or de l’année in the Ensemble and Florilegium, she was leader of Baroque Ensemble category for her The English Concert from 1997 to 2002. In recording of the La Cetra Vivaldi concertos 2004 Rachel began a guest directorship with with Holland Baroque and in 2014 she won a The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, BBC Music Magazine award in the instru touring Europe and the USA. -

Inner Lights Chamber Music for Flute Works by A

Inner Lights Chamber Music for Flute Works by A. Vivaldi, M. Marais, G. F. Handel, J. S. Bach and C. P. E. Bach Barbara Kortmann, Flute Inner Lights Barbara Kortmann, Flute Sabine Erdmann, Harpsichord Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) Concerto in D major, Op. 10, No. 3 “Il Cardellino” for Flute, String Orchestra and Basso continuo 01 Allegro ........................................................ (03'57) 02 Cantabile ...................................................... (03'14) 03 Allegro ........................................................ (02'51) Kerstin Linder-Dewan (1 st Violin), Julia Prigge (2 nd Violin), Nikolaus Schlierf (Viola), Julia Kursawe (Violoncello), Benjamin Wand (Double bass) Marin Marais (1656–1728) Les Folies d’Espagne for Flute (Viola da Gamba) and Basso continuo 04 ............................................................... (07'18) George Frideric Handel (1685 –1759) “Meine Seele hört im Sehen”, HWV 207 from Neun Deutsche Arien, HWV 202–210 for Flute, Violin and Basso continuo (arranged by Barbara Kortmann) 05 Andante ....................................................... (05'57) Kerstin Linder-Dewan (Violin), Julia Kursawe (Violoncello) Antonio Vivaldi Concerto in G minor, Op. 10, No. 2 “La Notte” for Flute, String Orchestra and Basso continuo 06 Largo .......................................................... (02'00) 07 Fantasmi (Presto) ............................................. (00'49) 08 Largo .......................................................... (01'19) 09 Presto ........................................................ -

R a I R a D I O 5 C L a S S I C a Domenica 06. 11. 2016

RAI RADIO5 CLASSICA sito web: www.radio5.rai.it e-mail: [email protected] SMS: 347 0142371 televideo pag. 539 Ideazione e coordinamento della programmazione a cura di Massimo Di Pinto gli orari indicati possono variare nell'ambito di 4 minuti per eccesso o difetto DOMENICA 06. 11. 2016 00:00 EUROCLASSIC NOTTURNO: musiche di grieg, edvard (1843-1907), kraus, joseph martin (1756-1792), farkas, ferenc (1905-2000), corelli, arcangelo (1653-1713), haydn, joseph (1732-1809), järnefelt, armas (1869-1958), sibelius, jan (1865-1957), britten, benjamin (1913-1976), mozart, wolfgang amadeus (1756-1791) e gade, niels wilhelm (1817-1890). 02:00 Il ritornello: riproposti per voi i programmi trasmessi ieri sera dalle ore 20:00 alle ore 24:00 06:00 ALMANACCO IN MUSICA: heinrich schütz (köstritz, 08/10/1585 - dresda, 06/11/1672): veni sancte spiritus, a 16 voci in 4 cori con b. c. - [7.16] - compl voc e strum "musicalische compagney" - cemb e dir. howard arman - jiri antonin benda (staré benátky, 30/06/1722 - köstritz, 06/11/1795): due sonatine per chit - [5.38] - andrés segovia, chit - piotr ciajkovskij (votkinsk, 07/05/1840 - san pietroburgo, 06/11/1893): la bella addormentata, suite dal balletto op. 66 - [20.04] - orch wiener philharmoniker dir. james levine - maurice ravel: daphnis et chloè, suite n. 2 dal balletto - [17.44] - orchestre de paris dir. charles münch (strasburgo, 26/09/1891 - richmond, 06/11/1968) 07:00 CONCERTO DEL MATTINO: bach, johann sebastian (1685-1750): sei preludi e fughe, da "il clavicembalo ben temperato" (libro I) - [28.23] - glenn gould, pf - haydn, joseph (1732-1809): quartetto per archi n. -

12:00:00A 00:00 Lunes, 12 De Julio De 2021 12A NO

*Programación sujeta a cambios sin previo aviso* LUNES 12 DE JULIO 2021 12:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 12 de julio de 2021 12A NO - Nocturno 12:00:00a 55:00 MÚSICA 12:55:00a 00:50 Identificación estación 01:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 12 de julio de 2021 1AM NO - Nocturno 01:00:00a 55:00 MÚSICA 01:55:00a 00:50 Identificación estación 02:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 12 de julio de 2021 2AM NO - Nocturno 02:00:00a 55:00 MÚSICA 02:55:00a 00:50 Identificación estación 03:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 12 de julio de 2021 3AM NO - Nocturno 03:00:00a 55:00 MÚSICA 03:55:00a 00:50 Identificación estación 04:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 12 de julio de 2021 4AM NO - Nocturno 04:00:00a 55:00 MÚSICA 04:55:00a 00:50 Identificación estación 05:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 12 de julio de 2021 5AM NO - Nocturno 05:00:00a 55:00 MÚSICA 05:55:00a 03:00 + HIMNO NACIONAL + 05:58:00a 00:50 Identificación estación 06:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 12 de julio de 2021 6AM MA - Mañanas 06:00:00a 10:00 ~PROGRAMA RTC~ 06:10:00a 11:27 Sonata p/2 violines en mi men. Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) Simon Standage y Micaela Comberti-violines 06:21:27a 11:57 Polonesa Op.44 en fa sost menor Frederic Chopin (1810-1849) Evgenny Kissin-piano 06:33:24a 15:20 *La victoria de Wellington Op. 91 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Erich Kunzel Sinfónica de Cincinnati 06:48:44a 00:50 Identificación estación 07:00:00a 00:00 lunes, 12 de julio de 2021 7AM MA - Mañanas 07:00:00a 15:20 Sonata no.6 p/violín y clavecín BWV1019 en Sol May. -

CHAN 0541 Cover 3/18/05 11:17 AM Page 1

CHAN 0541 Cover 3/18/05 11:17 AM Page 1 CHAN 0541 CHACONNE CHANDOS early music CHAN 0541 BOOK.qxd 12/9/06 2:21 pm Page 2 Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714–1788) Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Trio Sonata in B flat major 19:36 Harpsichord Sonata in A major, H 186 15:55 in B-Dur • en si bémol majeur in A-Dur • en la majeur 1 I Allegro 6:43 10 I Allegro assai 5:46 2 II Adagio ma non troppo 6:02 11 II Poco adagio 4:39 3 III Allegretto 6:47 12 III Allegro 5:26 Franz Benda (1709–1786) Johann Gottlieb Graun (1702/3–1771) Violin Sonata in A minor 13:02 Trio Sonata in G minor 9:37 in a-Moll • en la mineur in g-Moll • en sol mineur 4 I Allegro ma non tanto 5:18 13 I Adagio 2:50 5 II Andante 4:34 14 II Allegretto 3:56 6 III Presto e Scherzando 3:04 15 III Allegro assai 2:47 Frederick the Great (1712–1786) Flute Sonata in C major 8:29 in C-Dur • en ut majeur 7 I Grave 2:50 8 II Allegro 3:40 9 III Tempo giusto 1:54 2 3 CHAN 0541 BOOK.qxd 12/9/06 2:21 pm Page 4 Johann Joachim Quantz (1697–1773) Music from the Court of Frederick the Great Flute Concerto in A major 12:06 in A-Dur • en la majeur 16 I Allegro 3:50 ‘Those who seek art, true and clear Burney, ‘His Majesty… allotted four hours a 17 II Larghetto 4:22 philosophy, and wit should come here’, wrote day to the study, practice and performance 18 III Presto 3:48 Princess Elizabeth of Rheinsberg about of music’. -

FRONT HANDEL.Qxd 9/10/07 11:08 Am Page 1

FRONT HANDEL.qxd 9/10/07 11:08 am Page 1 Chan 0616 CHACONNE H ANDEL Volume 2 Concerti grossi, Op. 6 COLLEGIUM MUSICUM 90 Simon Standage CHANDOS early music CHAN 0616 BOOK.qxd 9/10/07 11:09 am Page 2 George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) Concerti grossi, Op. 6, Volume 2 Concerto grosso, Op. 6 No. 6 15:32 in G minor . g-Moll . sol mineur 1 I Largo affettuoso 3:19 AKG 2 II A tempo giusto 1:30 3 III Musette: Larghetto 5:21 4 IV Allegro 3:03 5 V Allegro 2:13 Concerto grosso, Op. 6 No. 7 13:42 in B flat major . B-Dur . si bémol majeur 6 I Largo 1:09 7 II Allegro 2:31 8 III Largo e piano 3:00 9 IV Andante 3:50 10 V Hornpipe 3:04 Concerto grosso, Op. 6 No. 8 14:55 George Frideric Handel in C minor . c-Moll . ut mineur 11 I Allemande 4:32 12 II Grave 1:48 13 III Andante allegro 1:45 14 IV Adagio 1:18 15 V Siciliana: Andante 3:58 16 VI Allegro 1:22 3 CHAN 0616 BOOK.qxd 9/10/07 11:09 am Page 4 Concerto grosso, Op. 6 No. 9 13:17 violin I Simon Standage* Giovanni Grancino, Milan 1685 in F major . F-Dur . fa majeur Miles Golding A. Mariani, Pesaro c. 1650 17 I Largo 1:34 Clare Salaman Thomas Smith, 1760 Stephen Bull Anon, Genoese (?), mid-18th century 18 II Allegro 3:28 Diana Terry Jacobus Stainer, 1671 19 III Larghetto 3:11 violin II Micaela Comberti* Fabrizio Senta, Turin c. -

Spring 2019/3 by Brian Wilson, Simon Thompson and Johan Van Veen

Second Thoughts and Short Reviews Spring 2019/3 By Brian Wilson, Simon Thompson and Johan van Veen Spring 2019/2 is here and Spring 2019/1 is here. Reviews are by Brian Wilson except where indicated [JV] or [ST]. A warm welcome to Johan van Veen and Simon Thompson as much appreciated contributors. Without their assistance and the inclusion of an ‘In Progress’ feature at the end, covering the reviews that I have been shamefully slow in completing, this would have been a very slim edition. I’m harping on about pricing variability again. Gwyn Parry-Jones has recently reviewed the Alto reissue of the Mravinsky recordings of the last three Tchaikovsky symphonies in glowing terms which I heartily endorse. Alto is a budget label, so I naturally expected this release to be less expensive than the 2-CD DG Originals set – except that one dealer is offering it for £8 and the DG for £7.75, while another is charging £15.42 for the Alto and £6.49 for the DG. Good as Alto’s transfers always are, the DG is mastered from the original tapes, so would be my preference even if the prices were level. Check out the DG as a download and you find that even mp3 is more expensive than the CDs from the first dealer and lossless, with booklet, almost twice the price – yet no physical product is involved. Worse still, Qobuz are asking £16.49 or £17.99 for lossless downloads of these recordings – two variants are offered. uk.7digital.com are asking £9.49 for the lossless download of the Alto, with £7.99 for mp3 (no booklet with either). -

Orquestra Barroca Casa Da Música

Orquestra Barroca Casa da Música Rachel Podger violino e direcção musical Pedro Castro oboé 10 Out 2020 · 18:00 Sala Suggia MECENAS PRINCIPAL CASA DA MÚSICA Maestrina Rachel Podger sobre o programa do concerto. VIMEO.COM/465326486 A CASA DA MÚSICA É MEMBRO DE Johann Sebastian Bach Ouverture [I] em Dó maior, BWV 1066 (c.1717-23; c.21min) Ouverture — Courante — Gavotte I & II — Forlane — Menuet I & II — Bourrée I & II — Passepied I & II Georg Philipp Telemann Sonata [a 5] em Fá menor, TWV 44:32 (c.1730?; c.7min) Adagio — Allegro — Largo — Presto Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Sinfonia em Sol maior, Wq182/1 (1773; c.12min) Allegro di molto — Poco adagio — Presto PAUSA — Comentários ao programa por Fernando Miguel Jalôto Johann Sebastian Bach Ouverture [II] em Lá menor, BWV 1067[R] (1717-23; c.24min) Ouverture — Rondeau — Sarabande — Bourrée I & II — Polonaise: Moderato & Double — Menuet — Badinerie Georg Philipp Telemann Concerto em Si bemol maior, TWV 44:43 (antes de 1740; c.8min) Allegro — Largo — Allegro Johann Sebastian Bach Concerto em Dó menor, para oboé, violino, cordas e baixo contínuo, BWV 1060R (c.1717-23; c.15min) Allegro — Adagio — Allegro Nach Französischer Art alemães se haviam distinguido na compo- und nach Italienischem Gusto1 sição de obras ao gosto francês, nomeada- mente suites — normalmente destinadas a Na segunda metade do século XVII, a influên- instrumentos solistas (cravo, alaúde, violino, cia cultural que a corte francesa de Luís XIV viola da gamba) ou pequenos grupos instru- exerceu por toda a Europa, mas muito parti- mentais — e, sobretudo, Ouvertures. cularmente no Norte e Centro da Alemanha, A Ouverture orquestral, ainda que nascida foi avassaladora e incontornável. -

Royal Academy of Music 2022/23 Prospectus Digital

YOUR FUTURE IS MUSIC’S FUTURE PROSPECTUS 2022/23 Music must always move forward. There has to be CONTENTS a place for new musicians to connect, collaborate and create. We are that place. An adventurous conservatoire where the traditions of the past 3 INTRODUCTION 42 OUR DEPARTMENTS meet the talent of the future. 6 A message from our Principal 44 Accordion Our mission: to create 8 Imagine yourself here 46 Brass the music that will move 48 Choral Conducting 10 ABOUT THE ACADEMY 50 Composition and the world tomorrow. 12 Music’s future starts here Contemporary Music 14 Into our third century 52 Conducting 16 Sending music to the world 54 Guitar 17 Creative partners 56 Harp 58 Historical Performance 18 STUDENT LIFE 60 Jazz 20 Your future is music’s future 62 Musical Theatre 22 The new generation 64 Opera 24 Meet your mentor 66 Organ 26 Learn by performing 68 Piano 27 Equal partners 70 Piano Accompaniment 28 Skills for life 72 Strings 30 Space to grow 74 Timpani and Percussion 31 Your stage awaits 76 Vocal Studies 32 Find knowledge, find inspiration 78 Woodwind 34 Musicians, united 36 All together now 80 OUR COURSES 38 London calling 82 Academy courses 40 Find your place 84 Undergraduates 41 Reaching outwards 85 One-year courses 86 Postgraduates 87 Postgraduate degrees 88 Postgraduate diplomas 90 Research 91 The art of collaboration 92 Open Academy This PDF document has been optimised for accessibility. 94 YOUR FUTURE STARTS HERE 96 The next step Royal Academy of Music ©2021 97 Ready to audition? Every effort has been made to ensure that the information included 98 Tuition fees in this prospectus is correct at the time of publication. -

Grandissima Gravita Rachel Podger Violin Brecon Baroque

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS SA 39217 Grandissima Gravita pisendel tartini veracini vivaldi violin rachel podger brecon baroque Alison McGillivray cello Daniele Caminiti lute & guitar Marcin Świątkiewicz harpsichord Rachel Podger Edinburgh Inter national Festival with Brecon Baroque; solo recitals at Eindhoven, here is probably no more inspira- Trondheim Barokk, Fundación Juan March “Ttional musician working today than (Madrid), Ohrdruf and Weimar (Germany), Podger” (Gramophone). Rachel Podger, and Canary Islands; collaborations with “the queen of the baroque violin” (Sunday I Fagiolini and bbc now as well as broad- Times), has established herself as a leading casts on bbc Radio 3, continued educa- interpreter of the Baroque and Classical tional work at Juilliard and the Royal music periods. She was the first woman to Academy of Music, and a residency at be awarded the prestigious Royal Academy Wigmore Hall. of Music/Kohn Foundation Bach Prize in Rachel has enjoyed countless collabora- October 2015. A creative programmer she tions as director and soloist with orchestras is the founder and Artistic Director of all over the world. Highlights include Brecon Baroque Festival and her ensemble Robert Levin, Jordi Savall, Masaaki Brecon Baroque, and was resident artist at Suzuki, The Academy of Ancient Music, Kings Place for their 2016 season Baroque The European Union Baroque Orchestra, Unwrapped. Rachel celebrates her 50th Holland Baroque Society, Tafelmusik birthday in 2018 with a much-anticipated (Toronto), The English Concert, and recording of Bach cello suites on violin, a within the usa the Philharmonia Baroque recording of Vivaldi Four Seasons, and an Orchestra, San Francisco Early Music, exciting and innovative collaboration with Berwick Academy, and the Oregon world-renowned a cappella group voces8, Bach Festival.