Chapter 1: Kentucky at the Time of Bethel Academy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Jessamine County, Kentucky, from Its Earliest Settlement to 1898

A history of Jessamine County, Kentucky, from its earliest settlement to 1898. By Bennett H. Young. S. M. Duncan associate author. Young, Bennett Henderson, 1843-1919. Louisville, Ky., Courier-journal job printing co., 1898. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/loc.ark:/13960/t9t159p0n Public Domain http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#pd We have determined this work to be in the public domain, meaning that it is not subject to copyright. Users are free to copy, use, and redistribute the work in part or in whole. It is possible that current copyright holders, heirs or the estate of the authors of individual portions of the work, such as illustrations or photographs, assert copyrights over these portions. Depending on the nature of subsequent use that is made, additional rights may need to be obtained independently of anything we can address. 14 Hutory of Jesmmine Counti/, Kentucky. mained after the terrible fatality of Ruddell's and Martin's stations in June, 1780. The land law enacted by the Mrginia Legislature, in the set- tling of land made location easy and popular. The wonderful ac- counts of the fertility, beauty and salubrity of Kentucky turned an immense tide of immigration to the state. In 1782, the popula- tion did not exceed 1500; in 1790, it had grown to 61,133 white people; 114 colored free people, and 12,340 slaves ; a total of y;^- Gyy, while ten years later, in 1800. it had 179,873 white, 739 free colored, and 40,343 slaves; a total of 220,995, an increase in ten years of 224 1-2 per cent. -

Guide to Historic Sites in Kentucky

AMERICAN HERITAGE TRAVELER HERITAGE Guide t o Historic Sites in Kentucky By Molly Marcot Two historic trails, the Wilderness Bull Nelson on the site of this 62-acre Civil War Road and Boone’s Trace, began here park. The grounds contain the 1825 Battlefields and Coal and were traveled by more than 200,000 Pleasant View house, which became settlers between 1775 and 1818. In a Confederate hospital after the battle, 1. Middle Creek nearby London, the Mountain Life slave quarters, and walking trails. One National Battlefield Museum features a recreated 19th- mile north is the visitors center in the On this site in early 1862, volunteer Union century village with seven buildings, 1811 Rogers House, with displays that soldiers led by future president Col. James such as the loom house and barn, include a laser-operated aerial map of Garfield forced Brig. Gen. Humphrey which feature 18th-century pioneer the battle and a collection of 19th- Marshall’s 2,500 Confederates from the tools, rifles, and farm equipment. century guns. (859) 624-0013 or forks of Middle Creek and back to McHargue’s Mill, a half-mile south, visitorcenter.madisoncountyky.us/index.php Virginia. The 450-acre park hosts battle first began operating in 1817. Visitors reenactments during September. Two half- can watch cornmeal being ground and see mile trail loops of the original armies’ posi - more than 50 millstones. (606) 330-2130 Lexington Plantations tions provide views of Kentucky valleys. parks.ky.gov/findparks/recparks/lj www.middlecreek.org or and (606) 886-1341 or Bluegrass ) T H G I 4. -

General Geological Information for the Tri-States of Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee

General Geological Information for the Tri-States Of Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee Southeastern Geological Society (SEGS) Field Trip to Pound Gap Road Cut U.S. Highway 23 Letcher County, Kentucky September 28 and 29, 2001 Guidebook Number 41 Summaries Prepared by: Bruce A. Rodgers, PG. SEGS Vice President 2001 Southeastern Geological Society (SEGS) Guidebook Number 41 September 2001 Page 1 Table of Contents Section 1 P HYSIOGRAPHIC P ROVINCES OF THE R EGION Appalachian Plateau Province Ridge and Valley Province Blue Ridge Province Other Provinces of Kentucky Other Provinces of Virginia Section 2 R EGIONAL G EOLOGIC S TRUCTURE Kentucky’s Structural Setting Section 3 M INERAL R ESOURCES OF THE R EGION Virginia’s Geological Mineral and Mineral Fuel Resources Tennessee’s Geological Mineral and Mineral Fuel Resources Kentucky’s Geological Mineral and Mineral Fuel Resources Section 4 G ENERAL I NFORMATION ON C OAL R ESOURCES OF THE R EGION Coal Wisdom Section 5 A CTIVITIES I NCIDENTAL TO C OAL M INING After the Coal is Mined - Benefaction, Quality Control, Transportation and Reclamation Section 6 G ENERAL I NFORMATION ON O IL AND NATURAL G AS R ESOURCES IN THE R EGION Oil and Natural Gas Enlightenment Section 7 E XPOSED UPPER P ALEOZOIC R OCKS OF THE R EGION Carboniferous Systems Southeastern Geological Society (SEGS) Guidebook Number 41 September 2001 Page i Section 8 R EGIONAL G ROUND W ATER R ESOURCES Hydrology of the Eastern Kentucky Coal Field Region Section 9 P INE M OUNTAIN T HRUST S HEET Geology and Historical Significance of the -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

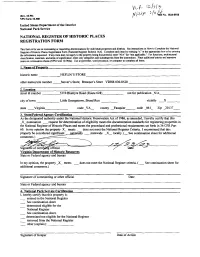

Lz,/, /:, '), /I I 1'T No. 1024.0018

V1_,f lz,/, /:, I No. 1024.0018 (Rev. 10-90) rJ f~(J-p '), /i 1't NPS Form 10-900 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This fonn is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking '"x" in the appropriate box or by entering the infonnation requested. If any item does not apply to the propeny being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Fonn I 0-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. I. Name of Property historic name ______HEFLIN'S STORE________________________ _ other names/site number -~Stover's Store; Brawner's Store VDHR 030-0520 --------------- 2. Location street & number _____5310 Blantyre Road (Route 628) _____ not for publication _ N/ A. ______ city of town ______ Little Georgetown, Broad Run _____ vicinity _x ____ state __Virginia ______ _ code_VA_ county _Fauquier___ code 061 Zip _20137 __ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _ X _ nomination _ request for detennination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Lake Union Herald � "Am I My Brother's Keeper?" Am a Debtor to All Men." � VOL

Lake Union Herald "Am I my brother's keeper?" am a debtor to all men." VOL. XXII BERRIEN SPRINGS, MICH., WEDNESDAY, JUNE 25, 1930 NO. 26 GOD'S LOVE brought new courage and life to- the members, as We can only see a little of the ocean well as to those who identified themselves with the A few miles distance from the rocky shore ; cause of God. The voice of Jesus is still speaking But out there—beyond, beyond our eyes' horizon, to the hearts of the people in a quiet, but very There's more—there's more! effective way. The Master is anxiously waiting• to We can only see a little of God's loving— bestow upon the sin-sick soul rest and peace. A few rich treasures from His mighty store; We appreciate very, much the united efforts of But out there—beyond, beyond our eyes' horizon, the laity, in connection with the workers, in saving There's more—there's more! —The Christian Index souls for the kingdom. As a result of these faithful and untiring labors, 299 were baptized into the WISCONSIN CONFERENCE precious faith. As workers, we are very anxious to OFFICE ADDRESS. P. 0. BOX 513. MADISON. WISCONSIN witness a steady growth in our thenibership ; and PRESIDENT. E. H. OSWALD therefore we solicit the prayers of our brethren and ••••••••••••....................*••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••. sisters. PRESIDENT'S REPORT Finances To the conference committee, workers, delegates, Our finances show a marked improvement. Two and brethren and sisters of the Wisconsin- Confer- years ago the united conference was burdened with ence assembled, Greeting: an .indebtedness of $114,000. -

Bluegrass Region Is Bounded by the Knobs on the West, South, and East, and by the Ohio River in the North

BOONE Bluegrass KENTONCAMPBELL Region GALLATIN PENDLETON CARROLL BRACKEN GRANT Inner Bluegrass TRIMBLE MASON Bluegrass Hills OWEN ROBERTSON LEWIS HENRY HARRISON Outer Bluegrass OLDHAM FLEMING NICHOLAS Knobs and Shale SCOTT FRANKLIN SHELBY BOURBON Alluvium JEFFERSON BATH Sinkholes SPENCER FAYETTE MONTGOMERY ANDERSONWOODFORD BULLITT CLARK JESSAMINE NELSON MERCER POWELL WASHINGTON MADISON ESTILL GARRARD BOYLE MARION LINCOLN The Bluegrass Region is bounded by the Knobs on the west, south, and east, and by the Ohio River in the north. Bedrock in most of the region is composed of Ordovician limestones and shales 450 million years old. Younger Devonian, Silurian, and Mississippian shales and limestones form the Knobs Region. Much of the Ordovician strata lie buried beneath the surface. The oldest rocks at the surface in Kentucky are exposed along the Palisades of the Kentucky River. Limestones are quarried or mined throughout the region for use in construction. Water from limestone springs is bottled and sold. The black shales are a potential source of oil. The Bluegrass, the first region settled by Europeans, includes about 25 percent of Kentucky. Over 50 percent of all Kentuckians live there an average 190 people per square mile, ranging from 1,750 people per square mile in Jefferson County to 23 people per square mile in Robertson County. The Inner Blue Grass is characterized by rich, fertile phosphatic soils, which are perfect for raising thoroughbred horses. The gently rolling topography is caused by the weathering of limestone that is typical of the Ordovician strata of central Kentucky, pushed up along the Cincinnati Arch. Weathering of the limestone also produces sinkholes, sinking streams, springs, caves, and soils. -

Bird Conservation Planning in the Interior Low Plateaus

Bird Conservation Planning in the Interior Low Plateaus Robert P. Ford Michael D. Roedel Abstract—The Interior Low Plateaus (ILP) is a 12,000,000 ha area has been dominated historically by oak-hickory forests, physiographic province that includes middle Kentucky, middle with areas of rock outcrops and glade habitats, prairies, and Tennessee, and northern Alabama. Spatial analysis of Breeding barrens (Martin and others 1993). All habitats now are highly Bird Atlas data has been used to determine relationships between fragmented. Currently, this project includes only Kentucky, the nature of high priority bird communities and broad features of Tennessee, and Alabama; the remainder of the ILP will be the habitat. A standardized vegetation classification using satellite incorporated later. Distinct subdivisions within the current imagery, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), GAP Analysis, scope of the project include the Bluegrass region and Shawnee and Breeding Bird Atlas data, were used to develop landscape-level Hills in Kentucky; the Western Highland Rim, Eastern High- habitat models for the ILP. The objectives of this effort were to: (1) land Rim, and Central Basin of Tennessee; and the Tennessee identify centers of abundance for species and/or species assem- River Valley of Alabama (fig. 1). These subdivisions serve as blages within the ILP, (2) identify and prioritize areas for potential distinct conservation planning units. About 95% of the land acquisition and/or public-private partnerships for conservation, (3) base consists of non-industrial forest lands, open lands for identify areas with the highest potential for restoration of degraded agriculture (pasture), and urban areas. Public lands and habitats, (4) identify specific lands managed by project cooperators lands managed by the forest products industry make up less where integration of nesting songbird management is a high prior- than 5% of the total area (Vissage and Duncan 1990). -

Wilmore Nicholasville Jessamine County Joint

WILMORE NICHOLASVILLE JESSAMINE COUNTY JOINT COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2010 Harold Rainwater Mayor City of Wilmore Russ Meyer Mayor City of Nicholasville William Neal Cassity County Judge / Executive Jessamine County City of Nicholasville Planning Commission Adopted March 22, 2010 Perry Barnes Shawn Murphy Danny Frederick John Quinn, Chairman Bennie Hager Brian Welch Linda Kentz Steve Williams Burton Ladd Robert L. Gullette, Jr., Attorney Gregory Bohnett, Director of Planning/Administrative Offi cer Jessamine County – City of Wilmore Joint Planning Commission Adopted January 10, 2010 Jane Ball, Secretary Steve Gayheart Pete Beaty, Chairman James McKinney, Vice Chairman Dave Carlstedt John Osborne Don Colliver Isaiah Surbrook Charles Fuller Eric Zablik Bruce E. Smith, Attorney Betty L. Taylor, Administrative Offi cer Wilmore Nicholasville i JessamineCounty Comprehensive Plan 2010 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN UPDATE COMMITTEE MEMBERS Gregory Bohnett, Chairman Rose Webster, Secretary Jeff Baier Wayne Foster Betty Taylor Pete Beaty Donald Hookum David West Paul Bingham Christopher Horne Troy Williams Dave Carlstedt Judy Miller Bobby Day Wilson John Collier Harold Mullis Lu Young George Dean John Quinn Dallam B. Harper, Planning Director Beth Jones, Regional Planner Kyle Scott, Regional Planner Wilmore Nicholasville JessamineCounty ii Comprehensive Plan 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Jessamine County Vision Statement ............................................................ 1 Introduction ................................................................................................... -

Ecoregions of Kentucky

Summary Table: Characteristics of the Ecoregions of Kentucky 6 8 . SOUTHWESTERN APPALACHIANS 7 1 . INTERIOR PLATEAU (continued) * * Level IV Ecoregion Physiography Geology Soil Climate Potential Natural Vegetation / Land Cover and Land Use Level IV Ecoregion Physiography Geology Soil Climate Potential Natural Vegetation / Land Cover and Land Use Present Vegetation Present Vegetation Area Elevation/ Surficial and Bedrock Order (Great Group) Common Soil Series Temperature/ Precipitation Frost Free Mean Temperature *Source: Küchler, 1964 Area Elevation/ Surficial and Bedrock Order (Great Group) Common Soil Series Temperature/ Precipitation Frost Free Mean Temperature * (square Local Relief Moisture Mean annual Mean annual January min/max; (square Local Relief Moisture Mean annual Mean annual January min/max; Source: Küchler, 1964 o miles) (feet) Regimes (inches) (days) July min/max ( F) miles) (feet) Regimes (inches) (days) July min/max (oF) 68a. Cumberland 607 Unglaciated. Open low hills, ridges, 980-1500/ Quaternary colluvium and alluvium. Ultisols (Hapludults). Shelocta, Gilpin, Latham, Mesic/ 47-51 170-185 23/46; Mixed mesophytic forest; American chestnut was a former dominant Mostly forest or reverting to forest. Also some 71d. Outer 4707 Glaciated in north. Rolling to hilly upland 382-1100/ Quaternary alluvium, loess, and in Mostly Alfisols Mostly Lowell, Cynthiana, Mesic/ 38-48. 160-210 20/45; Mostly oak–hickory forest. On Silurian dolomite: white oak stands Cropland, pastureland, woodland, military Plateau rolling uplands, and intervening valleys. 100-520 Mostly Pennsylvanian sandstone, shale, On floodplains: Entisols Muse, Clymer, Whitley, Udic. On 63/88 on drier sites/ On mesic sites: forests variously dominated by pastureland and limited cropland. Logging, Bluegrass containing small sinkholes, springs, 50-450 northernmost Kentucky, discontinuous (Hapludalfs, Fragiudalfs); Faywood, Beasley, Crider, Udic. -

Kentucky Landscapes Through Geologic Time Series XII, 2011 Daniel I

Kentucky Geological Survey James C. Cobb, State Geologist and Director MAP AND CHART 200 UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY, LEXINGTON Kentucky Landscapes Through Geologic Time Series XII, 2011 Daniel I. Carey Introduction The Ordovician Period Since Kentucky was covered by shallow The MississippianEarly Carboniferous Period 356 Ma Many types of sharks lived in Kentucky during the Mississippian; some had teeth for crinoid We now unders tand that the earth’s crust is broken up into a number of tropical seas du ring most of the Ordovician capturing swimming animals and others had teeth especially adapted for crushing and During most of the Ordovician, Kentucky was covered by shallow, tropical seas Period (Figs. 6–7), the fossils found in Sea Floor eating shellfish such as brachiopods, clams, crinoids, and cephalopods (Fig. 23). plates, some of continental size, and that these plates have been moving— (Fig. 4). Limestones, dolomites, and shales were formed at this time. The oldest rocks Kentucky's Ordovician rocks are marine (sea- Spreading Ridge Siberia centimeters a year—throughout geologic history, driven by the internal heat exposed at the surface in Kentucky are the hard limestones of the Camp Nelson dwelling) invertebrates. Common Ordovician bryozoan crinoid, Culmicrinus horn PANTHALASSIC OCEAN Ural Mts. Kazakstania of the earth. This movement creates our mountain chains, earthquakes, Limestone (Middle Ordovician age) (Fig. 5), found along the Kentucky River gorge in fossils found in Kentucky include sponges (of North China crinoid, corals crinoid, central Kentucky between Boonesboro and Frankfort. Older rocks are present in the Rhopocrinus geologic faults, and volcanoes. The theory of plate tectonics (from the Greek, the phylum Porifera), corals (phylum Cnidaria), cephalopod, PALEO- South China Rhopocrinus subsurface, but can be seen only in drill cuttings and cores acquired from oil and gas North America tektonikos: pertaining to building) attemp ts to describe the process and helps bryozoans, brachiopods (Fig. -

Land Character, Plants, and Animals of the Inner Bluegrass Region of Kentucky: Past, Present, and Future

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Biology Science, Technology, and Medicine 1991 Bluegrass Land and Life: Land Character, Plants, and Animals of the Inner Bluegrass Region of Kentucky: Past, Present, and Future Mary E. Wharton Georgetown College Roger W. Barbour University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Wharton, Mary E. and Barbour, Roger W., "Bluegrass Land and Life: Land Character, Plants, and Animals of the Inner Bluegrass Region of Kentucky: Past, Present, and Future" (1991). Biology. 1. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_biology/1 ..., .... _... -- ... -- / \ ' \ \ /·-- ........ '.. -, 1 ' c. _ r' --JRichmond 'I MADISON CO. ) ' GARRARD CO. CJ Inner Bluegrass, ,. --, Middle Ordovician outcrop : i lancaster CJ Eden Hills and Outer Bluegrass, ~-- ' Upper Ordovician outcrop THE INNER BLUEGRASS OF KENTUCKY This page intentionally left blank This page intentionally left blank Land Character, Plants, and Animals of the Inner Bluegrass Region of Kentucl<y Past, Present, and Future MARY E. WHARTON and ROGER W. BARBOUR THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this book was assisted by a grant from the Land and Nature Trust of the Bluegrass. Copyright © 1991 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, TI:ansylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.