Why the Public Trustee Model of Broadcast Television Must Fail - Abandoned in the Wasteland: Children, Television, and the First Amendment by Newton N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lightning Strikes Sanibei Serving Pizza at by Jill Tyrer Quick-Thinking Bystanders Rushed to His Aid

AUGUST 12, 1999 VOLUME 26 NUMBER 32 28 PAGES f:-V -159GO€O1OG64O9*CAR~RT SORT R003 """ ' - U SANlBfct LIBRARY d • "(10 O^NLOP KD 33957 SANlHfcL Ft .JORTER GOSS TALKS TO KIWANIS East end home invasion suspect remains at large By Pattie Pace Staff Writer An unidentified man entered the Lindgren Boulevard home of Sanibei woman in her 80s last Saturday and, after tying her hands and feet with a plastic-coated wire and placing a towel over head, fled with approximately $5,000 in jewelry and cash. According to Commander John Terry, the woman was quickly able to free her hands and call police. Officers Jane Cechman and Dave Jalbert arrived on scene within minutes of the call and found the woman in the bedroom. She was bruised and cut from being tied up, but otherwise not physically harmed, according to Terry. The burglar used a stick to poke the woman, but was other- wise unarmed. The officers searched her home and canvassed the neighborhood but could not find the intruder, described as a white male, approximately 40 years old, 5 feel 10 inches tall with a slender build and scraggly, blond chin-length hair. He wore a long-sleeve shirt with faint multicolored thin stripes, long pants, dirty brown work shoes with thick soles and loose untied laces, according to a police press release. » — * • Michael 1'iotdlu Police are asking anyone .who saw a man matching that U.S. Representative Porter Goss listens to a question at the Saiiibel/Captiva.Kiw:a*jiis, CJwb, •""'ctescrlptidn or i suspicion car-in the area of-Lindgren weekly breakfast at the Island House where he was the speaker. -

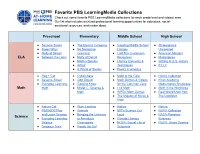

Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections Check out Some Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections for Each Grade Level and Subject Area

Favorite PBS LearningMedia Collections Check out some favorite PBS LearningMedia collections for each grade level and subject area. Our list also includes archived professional learning opportunities for educators, social- emotional resources, and maker ideas. Preschool Elementary Middle School High School ● Sesame Street ● The Electric Company ● Inspiring Middle School ● Shakespeare ● Super Why! ● No Nonsense Literacy Uncovered ● Molly of Denali Grammar ● LGBTQ+ Curriculum ● American Masters ELA ● Between the Lions ● Molly of Denali Resources ● Masterpiece ● Martha Speaks ● Literary Elements & ● Writing in U.S. History ● Arthur Techniques ● It’s Lit ● A World of Stories ● Poetry in America ● Peg + Cat ● Cyberchase ● Math at the Core ● NOVA Collection ● Sesame Street ● Odd Squad ● Math Games & Videos ● Khan Academy ● Everyday Learning: ● Good to Know for the Common Core Mathematics Showcase Math Math ● Mister C: Science & ● I <3 Math ● Math in the Workforce Math ● WPSU Math Games ● Real World Math from ● The Majesty of Music & The Lowdown Math ● Nature Cat ● Plum Landing ● Nature ● Nature ● PBS KIDS Play ● Animals ● MIT's Science Out ● NOVA Collection and Learn Science ● Bringing the Universe Loud ● NASA Planetary Science ● Everyday Learning: to America’s ● Climate Literacy Sciences Science Classrooms ● NOVA: Secret Life of ● NOVA: Gross Science ● Dinosaur Train ● Ready Jet Go! Scientists ● Let’s Go Luna ● All About the Holidays ● Teaching with Primary ● Access World Religions ● Xavier Riddle and ● NY State & Local Source Inquiry Kits -

Opening Worlds of Possibilities for Michiana's Children

Opening Worlds of Possibilities for Michiana’s Children PBS KIDS helps #1 EDUCATIONAL prepare children MEDIA for success in SOURCE school and life PBS aims at making a powerful difference in the lives of America’s children through high-quality, educational content. The number-one children’s educational media brand continues to push boundaries on innovation in teaching and learning across all platforms, including PBSLEARNINGMEDIA.ORG — which provides access to thousands of classroom-ready, curriculum-targeted digital resources such as videos, interactives, documents and in-depth lesson plans. The basic service is free for PreK-12 educators. PBS KIDS offers all children the opportunity to explore new ideas and new worlds through television, online, mobile and community-based programs. Parents, check out PBSPARENTS.ORG for information on child development and early learning through educational games and activities inspired by PBS KIDS programs. PBS provides innovative, cutting-edge platforms that are safe for kids of all ages Go to pbs.org or download your favorite PBS KIDS apps at PBSKIDS.ORG/APPS or by visiting the app stores. NEARLY 90% AGREE PBS IS A SAFE PLACE ONLINE AND ON TV PBS KIDS and The WNIT Kids Club gives kids a chance to WNIT Kids Club fully engage in what Public Television is all about … at a “Kid’s Level”! As an exclusive connect with the member you have the unique opportunity to local community engage with PBS KIDS characters through various events, on-air birthday mentions, discounts and a ton of other fun things. Call to enroll at 574-675-9648, x311. -

Children's DVD Titles (Including Parent Collection)

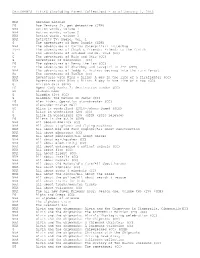

Children’s DVD Titles (including Parent Collection) - as of July 2017 NRA ABC monsters, volume 1: Meet the ABC monsters NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) PG A.C.O.R.N.S: Operation crack down (CC) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 PG Adventure planet (CC) TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) TV-G Adventures in babysitting (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Top gear trucks TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (2014) (SDH) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) PG The adventures of Panda Warrior (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with -

Menlo Park Juvi Dvds Check the Online Catalog for Availability

Menlo Park Juvi DVDs Check the online catalog for availability. List run 09/28/12. J DVD A.LI A. Lincoln and me J DVD ABE Abel's island J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Ociee Nash J DVD ADV The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin. J DVD ADV The adventures of Pinocchio J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE 2 Agent Cody Banks 2 J DVD AIR Air Bud J DVD AIR Air buddies J DVD ALA Aladdin J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALICE Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALL All dogs go to heaven J DVD ALL All about fall J DVD ALV Alvin and the chipmunks. -

July 2009 AETN Magazine

Contents AETN MAGAZINE Staff KUAR, KLRE, KUAF Editor in Chief ow that all AETN Allen Weatherly N On the Cover.........2 AETN would like to give a special transmitters are thanks to the above long-time Editors broadcasting in digital, Concert underwriters of American Masters. Mona Dixon Kathy Atkinson you can enjoy additional Reconnect............3 On The Cover.... streams of programming Editorial & Creative Directors From the AMERICAN MASTERS –Garrison Keillor: The Sara Willis on AETN Kids/Create and AETN Scholar! A lot of Director................4 Man on the Radio in the Red Shoes Elizabeth duBignon you have been asking what these channels are Wednesday, July 1, 7 p.m. (Repeats 7/4, 5:30 p.m.) Editorial Panel and how to get them. Simply put, a digital Outreach..............5 Rowena Parr, Pam Wilson, Dan Koops Lake Wobegon – where the women are strong, Tiffany Verkler signal can be broken up into sub-channels, and AETNFoundation the men are good looking and all the children are we have named our sub-channels Kids/Create Ambassadors above average – has become America’s collective Copy Editors Darbi Blencowe, Catherine Mays, and Scholar. The channels are already available Circle...................6 hometown, visited weekly for the past 40 years on Karen Cooper, Pat Pearce to watch over the air using an antenna with a fictional radio program that creates bona fide Production............7 AETN Offices a converter box or digital television. The main nostalgia. With his “Prairie Home Companion,” 350 S. Donaghey Ave. - Conway, AR - channel number will depend on which AETN channel Highlights.............8 Keillor became our national philosopher, filling 72034 800/662-2386 you watch, but the sub-channel will always be the PBS Ongoing the empty shoes of Will Rogers and Mark Twain, [email protected] - www.aetn.org same. -

Pub Type Edrs Price Descriptors

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 233 705 IR 010 796' TITLE Children and Television. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications, Consumer Protection, and Finance of the Committee on Energy and ComMerce, House of Representatives, Ninety-Eighth Congress, First Session. Serial No. 98-3. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Eneygy and Commerce. PUB DATE- 16 Mar 83 NOTE 221p.; Photographs and small print of some pages may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE --Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09'Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cable Television; *Childrens Television; Commercial Television; Educational Television; Federal Legislation; Hearings; Mass Media Effects; *ProgrAming (Broadcast); *Public Television; * Television Research; *Television Viewing; Violence IDENTIFIERS Congress 98th ABSTRACT Held, during National Children and Television Week, this hearing addressed the general topic of television and its impact on children, including specific ,children's televisionprojects and ideas for improving :children's television. Statements and testimony (when given) are presented for the following individuals and organizations: (1) John Blessington,-vice president, personnel, CBS/Broadcast Group; (2) LeVar Burton, host, Reading Rainbow; (3) Peggy Charren, president, National Action for Children's Television; (4) Bruce Christensen, president, National Association of;Public Television Stations; (5) Edward 0. Fritts, president, National Association of Broadcasters; (6) Honorable John A. Heinz, United States Senator, Pennsylvania; (7) Robert Keeshan, Captain Kangaroo; \(8) Keith W. Mielke, associate vice president for research, Children's Television Workshop; (9) Henry M. Rivera, Commissioner, , Federal Communications Commission; (10) Sharon Robinson, director, instruction and Professional Development, National Education Association; (11) Squire D. Rushnell, vice president, Long Range Planning and Children's Television, ABC; (12) John A. -

West Islip Public Library

CHILDREN'S TITLES (including Parent Collection) - as of January 1, 2013 NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a firefighter (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a zoo (CC) G African cats (SDH) PG Agent Cody Banks 2: destination London (CC) PG Alabama moon G Aladdin (2v) (CC) G Aladdin: the Return of Jafar (CC) PG Alex Rider: Operation stormbreaker (CC) NRA Alexander Graham Bell PG Alice in wonderland (2010-Johnny Depp) (SDH) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (CC) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (SDH) (2010 release) PG Aliens in the attic (SDH) NRA All aboard America (CC) NRA All about airplanes and flying machines NRA All about big red fire engines/All about construction NRA All about dinosaurs (CC) NRA All about dinosaurs/All about horses NRA All about earthquakes (CC) NRA All about electricity (CC) NRA All about endangered & extinct animals (CC) NRA All about fish (CC) NRA All about -

The Influence of Early Media Exposure on Children's Development And

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses July 2017 THE INFLUENCE OF EARLY MEDIA EXPOSURE ON CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENT AND LEARNING Katherine Hanson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Developmental Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Hanson, Katherine, "THE INFLUENCE OF EARLY MEDIA EXPOSURE ON CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENT AND LEARNING" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 1011. https://doi.org/10.7275/9875377.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1011 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF EARLY MEDIA EXPOSURE ON CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENT AND LEARNING A Dissertation Presented by KATHERINE G. HANSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2017 Psychology © Copyright by Katherine G. Hanson 2017 All Rights Reserved THE INFLUENCE OF EARLY MEDIA EXPOSURE ON CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENT AND LEARNING A Dissertation Presented by KATHERINE G. HANSON Approved as to style and content by: ________________________________________ Daniel R. Anderson, Chair ________________________________________ David Arnold, Member ________________________________________ Jennifer M. McDermott, Member ________________________________________ Erica Scharrer, Member ________________________________________ Hal Grotevant, Department Head Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Jennifer Kotler and Rosemarie Truglio for their support during my time at Sesame Workshop and their encouragement to go to graduate school. -

Program Listings

WXXI-TV/HD | WORLD | CREATE | AM1370 | CLASSICAL 91.5 | WRUR 88.5 | THE LITTLE PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFEBRUARY 2013 SUPER DRAMA 00 : SUNDAY FEBRUARY 3 STARTING AT 1PM ON WXXI-TV/HD 1 MANY LOVERS OF JANE AUSTEN If watching the Super Bowl on Sunday, February 3 isn’t your cup of tea, WXXI has a smashing alternative. Enjoy an afternoon of sophisticated television that we like to call Super Drama Sunday! We’ll kick off the afternoon at 1 p.m. with Many Lovers 00 of Jane Austen, which follows Austen expert and University of London Professor : Amanda Vickery as she traces the rise in popularity of Jane Austen novels. At 2 p.m., discover, if you haven’t 2 LARK RISE TO CANDLEFORD already, the heart-warming drama series Lark Rise to Candleford. An adaptation of Flora Thompson’s magical memoir of her Oxfordshire childhood, the series chronicles the daily lives of those living in the English Countryside. Then at 3 p.m., WXXI-TV gives you a 00 second chance to see episodes from season : three of the Emmy-award winning episodes from series Downton Abbey! Enjoy the first five episodes back to back. 3 DOWNTON ABBEY CLIFFORD TURNS 50! JOIN WXXI AT THE STRONG FOR A CELEBRATION FEBRUARY 2 AND 3 DETAILS INSIDE>> ANDREW ALDEN ENSEMBLE FEBRUARY 7 AT 7 PM & FEBRUARY 9 AT 3 PM, LITTLE THEATRE DETAILS INSIDE>> THE POWERBROKER: BLACK WHITNEY Young’S FIGHT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS MONDAY, FEBRUARY 25 AT 7 P.M. AT THE LITTLE THEATRE SCREENING AND PANEL DISCUSSION ARE FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC. -

KRWG Quarterly Program Topic Report April, May, June

KRWG Quarterly Program Topic Report April, May, June 2009 INTRODUCTION Through meetings with local community leaders, review of area newspapers and other publications, and production of a nightly newscast (Monday to Friday), the staff of KRWG-TV have determined that the following issues are of primary importance to the citizens within our coverage area: Health/Welfare/Safety – Petty crimes and drive-by shootings are an on-going problem in this area. While the over-all crime rate is no higher than the national average, low-income families and a higher than average teenage population contribute to the gang and crime problem. The chronic low-income family problem also results in health and welfare issues including an above average social services caseload and a high number of welfare cases handled by the local hospital. Culture – The mix of Hispanic/Native American/ and Anglo cultures provide many positive attributes to life in southern New Mexico. However, this same mix results in an on-going undercurrent of conflict among the cultures. Cultural and historical understanding is of on-going importance in this area. Business - With an above-average unemployment rate and a below-average income level, the status of the business/agricultural community in southern New Mexico is an important and on-going issue. Concern over the constant issue of defense spending at the federal level is ongoing in this area due to the presence of several military and NASA installations. Dona Ana county is also actively seeking new businesses and a strong infrastructure exists near the Santa Teresa Border Crossing, which is also a source of news and related issues. -

Echostar Launches New Noggin Network for Kids; DISH Network Teams up with Nickelodeon and Children's Television Workshop to Offer Educational Programming

EchoStar Launches New Noggin Network for Kids; DISH Network Teams Up With Nickelodeon and Children's Television Workshop to Offer Educational Programming LAS VEGAS--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Jan. 8, 1998--EchoStar Communications Corp. (NASDAQ: DISH, DISHP) announced today that it will add children's educational network Noggin to its America's Top 100 CD channel lineup. Noggin, a joint venture between America's foremost children's television programmers Nickelodeon and Children's Television Workshop, will be offered to America's Top 100 CD subscribers at no extra charge starting Tues., Feb. 2, 1999. The first 24-hour kids' thinking channel, Noggin's breakthrough mission will be to serve kids' (2-12) natural urge to learn by creating a new educational medium - one that combines television and on-line services, where learning starts with the click of a mouse. Noggin will explore topics and issues that kids say they care about while engaging them in regular conversation on-air and on-line to find out what they want to learn more about. "DISH Network is thrilled to add a network like Noggin made specifically to educate our children," said Michael Schwimmer, vice president of Programming for EchoStar. "DISH Network subscribers will now have access to the highest quality of children's educational television and to shows like Sesame Street and Electric Company that have taught and influenced our children for several generations." Noggin's programming schedule will feature the longest preschool block available on television (5 a.m. to 2 p.m. ET/PT), and will boast a cohesive mix of some of television's most acclaimed series from CTW and Nick Jr., including Blue's Clues, Sesame Street, Gullah Gullah Island and the Electric Company.