Learning from Television: a Research Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Semiconductor Industry | Accenture

GLOBALITY AND COMPLEXITY of the Semiconductor Ecosystem The semiconductor industry is a truly global affair. Around the world, semiconductor chip designers use intellectual property (IP) licenses and design verification to provide designs to wafer fabricators, which use raw silicon, photomasks, and equipment to create chips for package manufacturing to assemble with printed circuit board (PCB) substrates for delivery to end customers. In fact, components for a chip could travel more than 25,000 miles by the time it finds its way into a television set, mobile phone, automobile, computer, or any of the millions of products that now rely on chips to operate (Figure 1). 2 | Globality and Complexity of the Semiconductor Ecosystem Figure 1: Components for a chip could travel more than 25,000 miles before completion IP Licenses Euipment Modules Package Raw Silicon Manufacturing PC Substrates Asembly Standard Products and Test components Wafer Fabrication Equipment Chip Design Design Verification Photomask Wafer Manufacturing Fabrication The Global Semiconductor Alliance (GSA) and Accenture have teamed up to conduct a joint study on the globality and complexity of the semiconductor ecosystem to explore the interdependencies and benefits of the cross-border partnerships required to produce semiconductors, as well as to illustrate what’s needed to keep this global ecosystem operating efficiently and profitably. Industry executives can use this study to inform their company strategies, as well as to educate non-semiconductor partners, including policy makers, on the nature of their business to promote a better understanding of the important role semiconductors play in everyday life and on the globe-spanning ecosystem that’s needed to produce them. -

Television Device Ecologies, Prominence and Datafication: the Neglected Importance of the Set-Top Box

This is a repository copy of Television device ecologies, prominence and datafication: the neglected importance of the set-top box. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/146713/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Hesmondhalgh, D orcid.org/0000-0001-5940-9191 and Lobato, R (2019) Television device ecologies, prominence and datafication: the neglected importance of the set-top box. Media, Culture and Society, 41 (7). pp. 958-974. ISSN 0163-4437 https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719857615 © 2019, The Author(s). All rights reserved. This is an author produced version of a paper accepted for publication in Media, Culture and Society. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse See Attached Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Television device ecologies, prominence and datafication: the neglected importance of the set-top box David Hesmondhalgh, University of Leeds, UK Ramon Lobato, RMIT, Australia Accepted for publication by Media, Culture and Society, April 2019, due for online publication July 2019 Abstract A key element of the infrastructure of television now consists of various internet-connected devices, which play an increasingly important role in the distribution, selection and recommendation of content to users. The aim of this article is to locate the emergence of streaming devices within a longer timeframe of television hardware devices and infrastructures, by focusing on the evolution of one crucial category of such devices, television set-top boxes (STBs). -

Why the Public Trustee Model of Broadcast Television Must Fail - Abandoned in the Wasteland: Children, Television, and the First Amendment by Newton N

Alabama Law Scholarly Commons Articles Faculty Scholarship 1996 The Inevitable Wasteland: Why the Public Trustee Model of Broadcast Television Must Fail - Abandoned in the Wasteland: Children, Television, and the First Amendment by Newton N. Minow and Craig LaMay 1997 Survey of Books Relating to the Law: Legal Regulation and Reform Ronald J. Krotoszynski Jr. University of Alabama - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles Recommended Citation Ronald J. Krotoszynski Jr., The Inevitable Wasteland: Why the Public Trustee Model of Broadcast Television Must Fail - Abandoned in the Wasteland: Children, Television, and the First Amendment by Newton N. Minow and Craig LaMay 1997 Survey of Books Relating to the Law: Legal Regulation and Reform, 95 Mich. L. Rev. 2101 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ua.edu/fac_articles/220 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Alabama Law Scholarly Commons. THE INEVITABLE WASTELAND: WHY THE PUBLIC TRUSTEE MODEL OF BROADCAST TELEVISION REGULATION MUST FAIL Ronald J. Krotoszynski, Jr.* ABANDONED IN THE WASTELAND: CHILDREN, TELEVISION, AND TBE FIRST A~mNDmEr. By Newton N. Minow and Craig LaMay. New York: Hill & Wang. 1995. Pp. xi, 237. $11. More than thirty years ago, Newton N. Minow,1 then Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission ("Commission"), scolded broadcasters for failing to meet their obligations to the gen- eral public and, in particular, to the nation's children.2 Minow chal- lenged broadcasters to "sit down in front of your television set when your station goes on the air and stay there.. -

GFA Courses 1

GFA Courses 1 GFA 2020. GFA Lighting & Electric. 6-0-6 Units. GFA COURSES This course is designed to equip students with the skills and knowledge of electrical distribution and set lighting on a motion picture or episodic Courses television set in order to facilitate their entry and advancement in the GFA 1000. Intr to On-Set Film Production. 6-0-6 Units. film business. Students will participate in goal oriented class projects This course is the first of an 18-credit hour certificate program which including power distribution, set protocol and etiquette, properly setting will provide an introduction to the skills used in on-set film production, lamps, department lingo, how to light a set to feature film standards, including all forms of narrative media which utilize film-industry standard motion picture photography, etc. Upon completion of this course, the organizational structure, professional equipment and on- set procedures. student will have a very solid and broad base of knowledge that includes, In addition to the use of topical lectures, PowerPoint presentations, but is not limited to, the equipment, techniques, communications, videos and hand-outs, the course will include demonstrations of specifications, etc. used in the set lighting department. The student will equipment and set operations as well as hands-on learning experiences. also have a virtually complete understanding of the behavior of light and Students will learn: film production organizational structure, job how to manipulate and control it to feature film standards. descriptions and duties in various film craft areas, names, uses and GFA 2030. Grip & Rigging. 6-0-6 Units. -

SKY and TELEVISION WARRANTY INSURANCE POLICY This

Digital Care Partnership LTD 44-50 Old Christchurch Road Bournemouth, Dorset. BH1 1LN Tel: 0333 456 0418 Email:info@digitalcarepartnership. co.uk SKY AND TELEVISION WARRANTY INSURANCE POLICY This insurance policy has been arranged for you and is administered by Digital Care Partnership LTD, whose offices are situated at 44-50 Old Christchurch Road, Bournemouth, Dorset, BH1 1LN and who can be contacted on 0333 456 0418. Digital Care Partnership LTD is an appointed representative of European Speciality Risks Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Firm Reference Number 565023. Your insurer is Elite Insurance Company Limited. Registered in Gibraltar No. 91111 with a registered office at 47/48 The Sails, Queensway Quay, Queensway, Gibraltar GX11 1AA. Any questions, claims or complaints regarding this policy should initially be sent to Digital Care Partnership LTD or by telephoning them on 0333 456 0418. DEFINITIONS administratorwill send an engineer to you to repair Accidental Damage means the cost of repair to or replacement yourequipment. of your equipment following physical damage as a result of a sudden and unforeseen cause which stops the equipment working. In the event that your equipment cannot be repaired we will Administrator, Our, We or Us means Digital Care Partnership. replace yourequipment. If we cannot reasonably arrange a Breakdown means the cost of repair to or replacement of your replacement we will pay you a contribution towards the cost of equipment following a mechanical or electrical fault which replacing yourequipment for a television of a similar size and stops the equipment from working properly. -

Video Games: Changing the Way We Think of Home Entertainment

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 2005 Video games: Changing the way we think of home entertainment Eri Shulga Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Shulga, Eri, "Video games: Changing the way we think of home entertainment" (2005). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Video Games: Changing The Way We Think Of Home Entertainment by Eri Shulga Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Information Technology Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Copyright 2005 Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Master of Science in Information Technology Thesis Approval Form Student Name: _ __;E=.;r....;...i S=-h;....;..;u;;;..;..lg;;i..;:a;;...__ _____ Thesis Title: Video Games: Changing the Way We Think of Home Entertainment Thesis Committee Name Signature Date Evelyn Rozanski, Ph.D Evelyn Rozanski /o-/d-os- Chair Prof. Andy Phelps Andrew Phelps Committee Member Anne Haake, Ph.D Anne R. Haake Committee Member Thesis Reproduction Permission Form Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Master of Science in Information Technology Video Games: Changing the Way We Think Of Home Entertainment L Eri Shulga. hereby grant permission to the Wallace Library of the Rochester Institute of Technofogy to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. -

Instructional Television As a Medium of Teaching in Higher Education

INSTRUCTIONAL TELEVISION AS A MEDIUM OF TEACHING IN HIGHER EDUCATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Harold Franklin Niven, Jr., E. A. , A.M. The Ohio State University 1958 Approved by Adviser Department of Education TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I THE UTILIZATION OF TELEVISION AS AN EDUCATIONAL MEDIUM ............................. 1 II HIGHER EDUCATION AND INSTRUCTIONAL TELEVISION...................................... 20 III THE DEVELOPMENT OF TELEVISION AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION IN HIGHER EDUCATION........... 31 IV PRINCIPLES OF LEARNING RELEVANT TO INSTRUCTIONAL TELEVISION....................... 52 V AN EVALUATION OF INSTRUCTIONAL TELEVISION RESEARCH......................................... 65 VI THE ROLE OF THE TEACHER IN INSTRUCTIONAL TELEVISION............... 113 VII ATTITUDES AND OPINIONS OF FACULTIES AND STUDENTS TOWARD INSTRUCTIONAL TELEVISION . 125 VIII PRACTICAL FACTORS IN INSTRUCTIONAL TELEVISION................................. 145 IX CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS.............. 161 BIBLIOGRAPHY .......................................... 175 APPENDIX A. INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION USING CLOSE D-C IRC LIT TELEVISION............185 APPENDIX B. A PARTIAL LIST OF COURSES THAT HAVE BEEN TAUGHT, COMPLETELY OR IN PART, BY INSTRUCTIONAL TELEVISION IN INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION .... 193 APPENDIX C. ELECTRONIC COMPANIES ENGAGED IN CLOSED- CIRCUIT TELEVISION—SYSTEM ENGINEERING OR IN HIE MANUFACTURE -

Improving the Efficiency of Television Set-Top Boxes (PDF)

NRDC: Better Viewing, Real Savings, and Less Pollution - Improving the Efficiency of Television Set-Top Boxes (PDF) Energy Facts Better Viewing, Lower Energy Bills, and Less Pollution: Improving the Efficiency of Television Set-Top Boxes More than 80 percent of U.S. homes subscribe to some form of pay television service. Transforming those signals into shows, movies, and sports on the screen currently depends on approximately 160 million set-top boxes, nearly all of which are owned and installed by the cable, satellite, phone, or other service provider. NRDC and Ecos partnered to better understand how much energy these devices use and what energy savings opportunities exist. What we found was startling: In 2010, set-top boxes in the United States consumed approximately 27 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity, which is equivalent to the annual output of nine average (500 MW) coal-fired power plants. The electricity required to operate all U.S. boxes is equal to the annual household electricity consumption of the entire state of Maryland, results in 16 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, and costs households more than $3 billion each year. Fortunately, there is great potential for improving the efficiency and reducing the cost of operating these electronics relied upon by so many viewers. Key Findings n There are approximately 160 million set-top boxes installed n Better designed pay-TV set-top boxes could reduce the in U.S. homes. Almost all of these boxes are owned and energy use of the installed base of boxes by 30 percent installed by the service provider (e.g. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Lightning Strikes Sanibei Serving Pizza at by Jill Tyrer Quick-Thinking Bystanders Rushed to His Aid

AUGUST 12, 1999 VOLUME 26 NUMBER 32 28 PAGES f:-V -159GO€O1OG64O9*CAR~RT SORT R003 """ ' - U SANlBfct LIBRARY d • "(10 O^NLOP KD 33957 SANlHfcL Ft .JORTER GOSS TALKS TO KIWANIS East end home invasion suspect remains at large By Pattie Pace Staff Writer An unidentified man entered the Lindgren Boulevard home of Sanibei woman in her 80s last Saturday and, after tying her hands and feet with a plastic-coated wire and placing a towel over head, fled with approximately $5,000 in jewelry and cash. According to Commander John Terry, the woman was quickly able to free her hands and call police. Officers Jane Cechman and Dave Jalbert arrived on scene within minutes of the call and found the woman in the bedroom. She was bruised and cut from being tied up, but otherwise not physically harmed, according to Terry. The burglar used a stick to poke the woman, but was other- wise unarmed. The officers searched her home and canvassed the neighborhood but could not find the intruder, described as a white male, approximately 40 years old, 5 feel 10 inches tall with a slender build and scraggly, blond chin-length hair. He wore a long-sleeve shirt with faint multicolored thin stripes, long pants, dirty brown work shoes with thick soles and loose untied laces, according to a police press release. » — * • Michael 1'iotdlu Police are asking anyone .who saw a man matching that U.S. Representative Porter Goss listens to a question at the Saiiibel/Captiva.Kiw:a*jiis, CJwb, •""'ctescrlptidn or i suspicion car-in the area of-Lindgren weekly breakfast at the Island House where he was the speaker. -

Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections Check out Some Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections for Each Grade Level and Subject Area

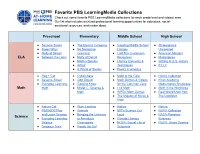

Favorite PBS LearningMedia Collections Check out some favorite PBS LearningMedia collections for each grade level and subject area. Our list also includes archived professional learning opportunities for educators, social- emotional resources, and maker ideas. Preschool Elementary Middle School High School ● Sesame Street ● The Electric Company ● Inspiring Middle School ● Shakespeare ● Super Why! ● No Nonsense Literacy Uncovered ● Molly of Denali Grammar ● LGBTQ+ Curriculum ● American Masters ELA ● Between the Lions ● Molly of Denali Resources ● Masterpiece ● Martha Speaks ● Literary Elements & ● Writing in U.S. History ● Arthur Techniques ● It’s Lit ● A World of Stories ● Poetry in America ● Peg + Cat ● Cyberchase ● Math at the Core ● NOVA Collection ● Sesame Street ● Odd Squad ● Math Games & Videos ● Khan Academy ● Everyday Learning: ● Good to Know for the Common Core Mathematics Showcase Math Math ● Mister C: Science & ● I <3 Math ● Math in the Workforce Math ● WPSU Math Games ● Real World Math from ● The Majesty of Music & The Lowdown Math ● Nature Cat ● Plum Landing ● Nature ● Nature ● PBS KIDS Play ● Animals ● MIT's Science Out ● NOVA Collection and Learn Science ● Bringing the Universe Loud ● NASA Planetary Science ● Everyday Learning: to America’s ● Climate Literacy Sciences Science Classrooms ● NOVA: Secret Life of ● NOVA: Gross Science ● Dinosaur Train ● Ready Jet Go! Scientists ● Let’s Go Luna ● All About the Holidays ● Teaching with Primary ● Access World Religions ● Xavier Riddle and ● NY State & Local Source Inquiry Kits -

The Influence of Cinema and Television on Tourism

THE INFLUENCE OF CINEMA AND TELEVISION ON TOURISM PROMOTION Raquel Sola Real y Claudia Medina Herrera Universidad de La Laguna Abstract In a world where television and cinema productions are becoming more and more alluring, the power of attraction that they can exert over people is unquestionable. This work revolves around the previous idea, going through countries that have benefited from film-induced tourism –from the USA to the UK, without forgetting New Zealand. After explaining new emerging forms of marketing related to this kind of tourism (place branding), we end up analyzing the past and current situation of shootings in Spain, and more specifically, in the Canary Islands. Keywords: Film-induced tourism, place branding, shootings in Spain, shootings in the Canary Islands. LA INFLUENCIA DEL CINE Y LA TELEVISIÓN EN LA PROMOCIÓN TURÍSTICA Resumen En un mundo donde las producciones televisivas y cinematográficas son cada vez más fas- 9 cinantes, es incuestionable el poder de atracción que estas ejercen sobre las personas. Este trabajo gira en torno a esa idea, examinando la situación de diferentes países que se han beneficiado del turismo cinematográfico: desde Estados Unidos hasta Reino Unido, sin olvidarnos de Nueva Zelanda. Tras explicar nuevas formas de marketing relacionadas con este tipo de turismo como el place branding, terminaremos analizando el pasado y presente de España y las Islas Canarias en cuanto a rodajes y situación audiovisual se refiere. Palabras clave: turismo cinematográfico, place branding, rodajes en España, rodajes en las Islas Canarias. REVISTA LATENTE, 16; 2018, PP. 9-36 PP. REVISTA LATENTE, 2018, 16; DOI: http://doi.org/10.25145/j.latente.2018.16.001 Revista Latente, 16; diciembre 2018, pp.