Ensaio Para Rbecotur N\372Mero 10 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lawin Modern Society Lawin Modern Society

LAWIN MODERN SOCIETY LAWIN MODERN SOCIETY Toward a Criticism of Social Theory Roberto Mangabeira Unger l�I THE FREE PRESS New York lffil THE FREE PRESS 1230 Avenueof theAmericas New York, NY 10020 Copyright© 1976 by RobertoMangabeira Unger All rights reserved, including theright of reproduction in whole or in partin anyform. THE FREEPRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc. First Free Press Paperback Edition 1977 Manufacturedin the United Statesof America Paperbound printing number 10 Unger,Library ofRoberto Congress Mangabeira. Cataloging in Publication Data Law in modern society. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Sociological jurisprudence. I. Title. Law 34o.1'15 74-27853 ISBN 0-02-932880-2 pbk. NOTE This study builds upon my Knowledge and Politics (Free Press, 1975). To make the present work intelligibleto readers unfamiliar with Knowledge and Politics, it wa,; necessary in some cases to restate ideas developed in the earlier book. CONTENTS CHAPTER1. The Predicament of Social Theory 1 The "burden of the past" in social theory 1 Social theory and political philosophy 3 The unity and crisis of social theory 6 The problem of method 8 The problem of social order 23 The problem of modernity 37 Human nature and history 40 Law 43 CHAPTER2. Law and the Forms of Society 47 The problem 47 Three concepts of law 48 The emergence of bureaucratic law 58 The separation of state and society 58 The disintegration of community 61 The division of labor and social hierarchy 63 The tension within bureaucratic law 64 The emergence of a legal order 66 Group pluralism 66 Natural law 76 Liberal society and higher law 83 VII viii I Contents The Chinese case: a comparative analysis 86 The hypothesis 86 Custom and "feudalism" in early China 88 The transformation period: from custom to bureaucratic law 96 Confucianists and Legalises 105 Limits of the Chinese comparison: the experience of other civilizations 110 The sacred laws of ancient India, Islam, and Israel 110 The Graeco-Roman variant 120 Law as a response to the decline of order 127 CHAPTER 3. -

Katherine-Mckittrick-Sylvia-Wynter-On

Sylvia Wynter Sylvia Wynter ON BEING HUMAN AS PRAXIS Katherine McKittrick, ed. Duke University Press Durham and London 2015 © 2015 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Graphic Composition, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sylvia Wynter : on being human as praxis / Katherine McKitrick, ed. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5820- 6 (hardcover : alk. Paper) isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5834- 3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Wynter, Sylvia. 2. Social sciences—Philosophy. 3. Civilization, Modern—Philosophy. 4. Race—Philosophy. 5. Human ecology—Philosophy. I. McKitrick, Katherine. hm585.s95 2015 300.1—dc23 2014024286 isbn 978- 0- 8223- 7585- 2 (e- book) Cover image: Sylvia Wynter, circa 1970s. Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Te New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (sshrc / Insight Grant) which provided funds toward the publication of this book. For Ellison CONTENTS ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Katherine McKitrick 1 CHAPTER 1 Yours in the Intellectual Struggle: Sylvia Wynter and the Realization of the Living Sylvia Wynter and Katherine McKitrick 9 CHAPTER 2 Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species? Or, to Give Humanness a Diferent Future: Conversations Denise Ferreira da Silva 90 CHAPTER 3 Before Man: -

Full Report Should Be Available Shortly

Climate Cliange 1992 The supplementary report to the IPCC Impacts Assessment Climate Change 1992 The supplementary report to the IPCC Impacts Assessment Edited by W J McG Tegart and G W Sheldon Australian Government Publishing Service Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 1993 ISBN 0 644 25150 6 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Australian Government Publishing Service. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be add|ressed to the Manager, Commonwealth Information Services, Australian Government Publishing Service, GPO Box 84, Canberra ACT 2601. Published for the Department of the Arts, Sport, the Environment and Territories by the Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra Cover illustration: Island in the Maldives (courtesy of Austral International, Sydney) Printed on 100 per cent recycled paper Printed in Australia by A. J. LAW, Commonwealth Government Printer, Canberra Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Climate Change 1992 The Supplementary Report to the IPCC Impacts Assessment Report prepared for IPCC by Working Group II Chairman: Professor Yu A Izrael (Russia) Co-Vice-chairmen: Professor O Canziani (Argentina), Dr Hashimoto (Japan), Professor O S Odingo (Kenya), Dr W J McG Tegart (Australia) Contents Preface by Professor GOP Obasi (WMO) and Dr M K Tolba (UNEP) ix Preface by Professor Bert Bolin, Chairman, IPCC x Preface by Professor Yu A Izrael, Chairman, Working -

Living Planet Report 2008 Contents

LIVING PLANET REPORT 2008 CONTENTS Foreword 1 WWF EDITOR IN CHIEF WWF INTERNATIONAL (also known as World Wildlife Chris Hails Avenue du Mont-Blanc Fund in the USA and Canada) is CH-1196 Gland INTRODUCTION 2 one of the world’s largest and EDITORS Switzerland Biodiversity, ecosystem services, humanity’s most experienced independent Sarah Humphrey www.panda.org conservation organizations, with Jonathan Loh footprint 4 almost 5 million supporters and Steven Goldfinger INSTITUTE OF ZOOLOGY a global network active in over Zoological Society of London CONTRIBUTORS EVIDENCE 6 100 countries. WWF’s mission is Regent’s Park to stop the degradation of the WWF London NW1 4RY, UK Global Living Planet Index 6 planet’s natural environment and Sarah Humphrey www.zoo.cam.ac.uk/ioz/projects/ Systems and biomes 8 to build a future in which humans Ashok Chapagain indicators_livingplanet.htm live in harmony with nature. Biogeographic realms 10 Greg Bourne Richard Mott GLOBAL FOOTPRINT NETWORK Taxa 12 Judy Oglethorpe 312 Clay Street, Suite 300 Ecological Footprint of nations 14 ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY Aimee Gonzales Oakland, California 94607 OF LONDON Martin Atkin USA Biocapacity 16 Founded in 1826, the Zoological www.footprintnetwork.org Water footprint of consumption 18 Society of London (ZSL) is ZSL Jonathan Loh Water footprint of production 20 an international scientific, TWENTE WATER CENTRE conservation and educational Ben Collen University of Twente organization. Its mission is to Louise McRae 7500 AE Enschede TURNING THE TIDE 22 achieve and promote the Tharsila T. Carranza The Netherlands worldwide conservation of Fiona A. Pamplin www.water.utwente.nl Towards sustainability 22 animals and their habitats. -

Mt. Vernon Terrace $619,900

Spring 2014 HomeLifeStyleHomeLifeStyle Style Inside Life Mount Vernon’s Hometown Newspaper • A Connection Newspaper March 13, 2014 wLww oc.Caolnn Meecdtion ia CNeowsp nnaepcerts.c ioonm LLC Moonunt lin Vee rno at nw Gwaze wt.cteo n❖ n HeocmteiLo ifnenSetywles Sp apprinerg s2.c 01o4m ❖ 1 Home A Debt to Society Local governments use debt as a tool to build for the future. By Michael Lee Pope ing economy that will enable them Photo by Photo The Gazette to pay off the debt.” Fairfax County has the largest ack in the 1920s, Harry debt by far, almost $4 billion. But Byrd became governor of Fairfax also has more people than Janelle Germanos Janelle B Virginia on what he called any of the other jurisdictions. So a “pay-as-you-go” platform. Byrd the county’s per capita debt bur- had an almost pathological hatred den is actually lower than Arling- of debt, fueled in part by mount- ton or Alexandria. Financial re- ing debt problems of his family’s ports show that local governments business. Now, almost a century across Northern Virginia have /The Gazette later, leaders across Northern Vir- been taking on increasing debt in ginia have a very different view recent years, and some believe about the role debt should play in that trend might accelerate in the balancing the books. Local govern- near future. Because Congress is ments across Virginia have taken considering eliminating some ex- A view from the top of the landfill in Lorton. If the new application is approved, on more than $8 billion in debt. -

BB.Com Discog

Amy MacDonald The Human Demands Album Mix Jungle Forthcoming Album Mix Sam Fender Hypersonic Missiles Album Mix Dead Boys EP Mix Greasy Spoon Single Mix Friday Fighting Single Mix Poundshop Kardashians / Spice Single Mix Bad Sounds Ecaping From a Violent Time EP Mix Someday Jacob Oxygen Will Flow Album Mix Robert Francis Forthcoming Album Mix KYNSY Cold Blue Light Single Mix Skinny Lister The Story Is Album Produce / Mix Half Moon Run Sun Leads Me On Album Mix Jungle Heavy California Single Pre production Peace In Love Album Mix Patrick Wolf Lupercalia Album Tracks Mix The 1975 Chocolate Single Pre pro Stereophonics Keep Calm And Carry On Album Mix Everyone You Know Burning Down Single Mix Our Generation Single Mix Play God Single Mix Cheer up Charlie EP Mix Temper Trap Conditions Album Mix Sweet Disposition Single Mix Eugene McGuinness Early Learnings Album Mix MIA Agrular Album Tracks Mix James Yorkston When The Haar Rolls In Album Mix Bombay Bicycle Club I Had The Blues But I… Album Mix The Sunshine Underground Nobody’s Coming To Save You Album Produce / Mix The Noisettes Wild Young Hearts Album Mix Twilight - Breaking Dawn Soundtrack Soundtrack Mix Grace Savage Forthcoming EP Mix Maguire Préludes EP Mix Alex Luca Forthcoming EP Mix The Preatures Blue Planet Eyes Album Mix Alberta Cross The Thief & the Heartbreaker EP Produce / Mix Turin Brakes Outbursts Album Mix The Rakes Ten New Messages Album Mix The Enemy We’ll Live & Die in these Towns Album Produce / Mix VV Brown Travelling Like The Light Album Mix Mr Hudson & the Libary A Tale -

1 Introduction to Enzyme Technology

j1 1 Introduction to Enzyme Technology 1.1 Introduction Biotechnology offers an increasing potential for the production of goods to meet various human needs. In enzyme technology – a subfield of biotechnology – new processes have been and are being developed to manufacture both bulk and high added-value products utilizing enzymes as biocatalysts, in order to meet needs such as food (e.g., bread, cheese, beer, vinegar), fine chemicals (e.g., amino acids, vitamins), and pharmaceuticals. Enzymes are also used to provide services, as in washing and environmental processes, or for analytical and diagnostic purposes. The driving force in the development of enzyme technology, both in academia and in industry, has been and will continue to be the development of new and better products, processes, and services to meet these needs, and/or the improvement of processes to produce existing products from new raw mate- rials such as biomass. The goal of these approaches is to design innovative products and processes that not only are competitive but also meet criteria of sustainability. The concept of sus- tainability was introduced by the World Commission on Environment and Develop- ment (WCED, 1987) with the aim to promote a necessary “. development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future genera- tions to meet their own needs.” This definition is now part of the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity, an international treaty govern- ing the movements of living modified organisms (LMOs) resulting from modern biotechnology from one country to another. It was adopted on January 29, 2000 as a supplementary agreement to the Convention on Biological Diversity and entered into force on September 11, 2003 (http://bch.cbd.int/protocol/text/). -

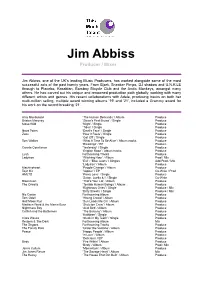

Jim Abbiss Complete CV.Pdf

Jim Abbiss Producer / Mixer Jim Abbiss, one of the UK’s leading Music Producers, has worked alongside some of the most successful acts of the past twenty years. From Bjork, Sneaker Pimps, DJ shadow and U.N.K.LE through to Placebo, Kasabian, Bombay Bicycle Club and the Arctic Monkeys, amongst many others. He has carved out his unique and renowned production path globally, working with many different artists and genres. His recent collaborations with Adele, producing tracks on both her multi-million selling, multiple award winning albums '19' and '21', included a Grammy award for his work on the record breaking ‘21’. Amy Macdonald ‘The Human Demands’ / Album Produce Briston Maroney ‘Steve’s First Bruise’ / Single Produce Mosa Wild ‘Night’ / Single Produce ‘Tides’ / Single Produce Nova Twins ‘Devil’s Face’ / Single Produce Zuzu ‘How It Feels’ / Single Produce ‘Get Off’ / Single Produce Tom Walker ‘What A Time To Be Alive’ / Album tracks Produce ‘Blessings’ / EP Produce Connie Constance ‘Yesterday’ / Single Produce ‘English Rose’ / Album tracks Produce Lush Forthcoming Tracks Produce Ladytron ‘Witching Hour’ / Album Prod / Mix ‘Evil’ / ‘Blue Jeans’ / Singles Add Prod / Mix ‘Ladytron’ / Album Produce Machineheart ‘People Change’ / Album Produce Tojin Kit ‘Vapour’ / EP Co-Write / Prod HMLTD ‘Proxy Love’ / Single Produce ‘Satan, Luella & I’ / Single Co-Write Blaenavon ‘That’s Your Lot’ / Album Produce The Orwells ‘Terrible Human Beings’ / Album Produce ‘Righteous Ones’ / Single Produce / Mix ‘Dirty Sheets’ / Single Produce / Mix Nic Cester Forthcoming -

Interview Amy Macdonald

INTERVIEW AMY MACDONALD Mon pèrem’a raconté quepeu de temps aprèsavoir rencontrémamère, il adécidédefaire un truc dingueavec elle et de partir àl’aventurequelque part.Ils ontdébarquéfauchés et sans logementàNew York,qui n’était pasun endroitglamour dans les années 1970. Ils ontfini dans un hôtelhorrible,avec unechambre dont la porte avait trois serrures parceque le quartier était dan- gereux. Je ne m’attendais pasàceque mes parentsaient pris de tels risques. Et cela m’afaitréfléchir àmaproprevie. Je passebeaucoupdetemps àrêvasser et je pense quecela est très important quand j’écris des chansons. Je me suis donc demandé àquoiaurait ressemblé ma viesij’avais choisi un autrechemin, si je ne m’étais paslancée dans la mu- siqueousijen’avais pasrencontré mon mari. Le genredequestions qu’onse pose tousparfoisetdontonneconnaî- trajamaisles réponses. J’ai tissé toutes La chanteuse et compositrice Amy Macdonald, passionnée cesidées ensemble et c’estcomme ça de foot et des Glasgow Rangers, aépouséen2018 le quecette chanson avulejour. footballeur RickyFoster,actuellement au Partick Thistle FC. Vous êtes d’humeur plutôt méditativeetnostalgique… ris un peu!», cela n’est pastrèsutile.On doncpum’offrirdebelles voitures et Totalement. Je croisque quand je me peut se retrouverdansune situation des choses comme ça. Quand on aeule suis mariée,quelque choseachangé où rien ne semble pouvoir nous faire plaisirdeconduireune Ferrari, une en moi. J’ai eu l’impression de devenir aller mieux. J’ai des amis quiont vécu Lamborghini et une RangeRover,c’est adulteetcela m’apoussée àréfléchir à ça et sontheureusementressortis du durderevenir en arrièreetconduire ma viemais aussi àcelle de ma famille tunnel. J’ai écrit ce titre en pensantà autrechose.Mais je croisqu’avec l’âge, et de mes amis. -

Living Planet Report 2008 Contents

LIVING PLANET REPORT 2008 CONTENTS Foreword 1 WWF EDITOR IN CHIEF WWF INTERNATIONAL (also known as World Wildlife Chris Hails Avenue du Mont-Blanc Fund in the USA and Canada) is CH-1196 Gland INTRODUCTION 2 one of the world’s largest and EDITORS Switzerland Biodiversity, ecosystem services, humanity’s most experienced independent Sarah Humphrey www.panda.org conservation organizations, with Jonathan Loh footprint 4 almost 5 million supporters and Steven Goldfinger INSTITUTE OF ZOOLOGY a global network active in over Zoological Society of London CONTRIBUTORS EVIDENCE 6 100 countries. WWF’s mission is Regent’s Park to stop the degradation of the WWF London NW1 4RY, UK Global Living Planet Index 6 planet’s natural environment and Sarah Humphrey www.zoo.cam.ac.uk/ioz/projects/ Systems and biomes 8 to build a future in which humans Ashok Chapagain indicators_livingplanet.htm . Biogeographic realms 10 live in harmony with nature Greg Bourne Richard Mott GLOBAL FOOTPRINT NETWORK Taxa 12 Judy Oglethorpe 312 Clay Street, Suite 300 Ecological Footprint of nations 14 ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY Aimee Gonzales Oakland, California 94607 OF LONDON Martin Atkin USA Biocapacity 16 Founded in 1826, the Zoological www.footprintnetwork.org Water footprint of consumption 18 Society of London (ZSL) is ZSL Jonathan Loh Water footprint of production 20 an international scientific, TWENTE WATER CENTRE conservation and educational Ben Collen University of Twente organization. Its mission is to Louise McRae 7500 AE Enschede TURNING THE TIDE 22 achieve and promote the Tharsila T. Carranza The Netherlands worldwide conservation of Fiona A. Pamplin www.water.utwente.nl Towards sustainability 22 animals and their habitats. -

Sgarbossa (1.117Mb)

Annual Reviews in Control 49 (2020) 295–305 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Annual Reviews in Control journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/arcontrol Human factors in production and logistics systems of the future ∗ Fabio Sgarbossa a, , Eric H. Grosse b,e, W. Patrick Neumann c, Daria Battini d, Christoph H. Glock e a Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, NTNU, S.P. Andersens vei 5, 7031, Trondheim, Norway b Juniorprofessorship of Digital Transformation in Operations Management, Saarland University, P.O. 151150, 66041 Saarbrücken Germany c Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Ryerson University, 350 Victoria St., Toronto, Canada d Department of Management and Engineering, University of Padova, Stradella San Nicola, 3 36100 Vicenza, Italy e Institute of Production and Supply Chain Management, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Hochschulstr. 1, 64289 Darmstadt, Germany a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The way humans work in production and logistics systems is changing. The evolution of technologies, Received 30 January 2020 Industry 4.0 applications, and societal changes, such as ageing workforces, are transforming operations Revised 9 April 2020 processes. This transformation is still a “black-box” for many companies, and there are calls for new Accepted 11 April 2020 management approaches that can help to successfully overcome the future challenges in production and Available online 16 May 2020 logistics. Keywords: While Industry 4.0 emerges, companies have started to use advanced control tools enabled by real-time Human Factor monitoring systems that allow the development of more accurate planning models that enable proac- Ergonomics tive managerial decision-making. -

Barny Barnicott CV.Pdf

Barny Barnicott Producer/Mixer Since his success with The Enemy’s debut No. 1 album ‘We’ll Live and Die in these Towns’, Barny has gained a reputation as one of the UK’s leading Mixers and Producers collaborating with artists from Elastica to the Sunshine Underground. This diverse catalogue has seen Barny develop a long- standing relationship with Jim Abbiss, mixing records for him such as Arctic Monkeys’ debut ‘Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not’ and The Temper Trap’s ‘Confessions’, all of which have been received to great international acclaim. Aziya Forthcoming Singles Mix GIRLI ‘Ex Talk’ / EP Mix Amy Macdonald ‘The Human Demands’ / Album Mix Sam Fender ‘Hypersonic Missiles’ / Album Mix ‘Dead Boys’ / EP Mix ‘Play God’ / Single Mix ‘Greasy Spoon’ / Single Mix ‘Friday Fighting’ / Single Mix ‘That Sound’ / Single Mix ‘Leave Fast’ / Single Mix ‘Spice’ / Single Mix ‘Poundshop Kardashians’ / Single Mix Everyone You Know ‘Burning Down’ / Single Mix ‘Our Generation’ / Single Mix ‘Play God’ / Single Mix ‘Cheer Up Charlie’ / EP Mix EYK X Joy Anonymous ‘Just For The Times’ / Single Mix Bad Sounds ‘Escaping From A Violent Time, Vol 1’ / EP Mix Someday Jacob ‘Oxygen Will Follow’ / Album Mix Robert Francis Forthcoming Album Mix KYNSY ‘Cold Blue Light’ / Single Mix Skinny Lister ‘The Story Is’ / Album Prod / Mix Half Moon Run ‘Sun Leads Me On’ / Album Mix Jungle ‘Heavy California’ / Single Pre Prod Patrick Wolf ‘Lupercalia’ / Album Tracks Mix The 1975 ‘Chocolate’ / Single Pre Prod Stereophonics ‘Keep Calm And Carry On’ / Album Mix Temper