C:\Documents and Settings\Sara\My Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sauces Reconsidered

SAUCES RECONSIDERED Rowman & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy General Editor: Ken Albala, Professor of History, University of the Pacific ([email protected]) Rowman & Littlefield Executive Editor: Suzanne Staszak-Silva ([email protected]) Food studies is a vibrant and thriving field encompassing not only cooking and eating habits but also issues such as health, sustainability, food safety, and animal rights. Scholars in disciplines as diverse as history, anthropol- ogy, sociology, literature, and the arts focus on food. The mission of Row- man & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy is to publish the best in food scholarship, harnessing the energy, ideas, and creativity of a wide array of food writers today. This broad line of food-related titles will range from food history, interdisciplinary food studies monographs, general inter- est series, and popular trade titles to textbooks for students and budding chefs, scholarly cookbooks, and reference works. Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam: Food and Drink in the Long Nine- teenth Century, by Erica J. Peters Three World Cuisines: Italian, Mexican, Chinese, by Ken Albala Food and Social Media: You Are What You Tweet, by Signe Rousseau Food and the Novel in Nineteenth-Century America, by Mark McWilliams Man Bites Dog: Hot Dog Culture in America, by Bruce Kraig and Patty Carroll A Year in Food and Beer: Recipes and Beer Pairings for Every Season, by Emily Baime and Darin Michaels Celebraciones Mexicanas: History, Traditions, and Recipes, by Andrea Law- son Gray and Adriana Almazán Lahl The Food Section: Newspaper Women and the Culinary Community, by Kimberly Wilmot Voss Small Batch: Pickles, Cheese, Chocolate, Spirits, and the Return of Artisanal Foods, by Suzanne Cope Food History Almanac: Over 1,300 Years of World Culinary History, Cul- ture, and Social Influence, by Janet Clarkson Cooking and Eating in Renaissance Italy: From Kitchen to Table, by Kath- erine A. -

Renaissance Food from Rabelais to Shakespeare

RENAISSANCE FOOD FROM RABELAIS TO SHAKESPEARE Renaissance Food from Rabelais to Shakespeare Culinary Readings and Culinary Histories Edited by JOAN FITZPATRICK Loughborough University, UK ASHGATE © The editor and contributors 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Joan Fitzpatrick has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editor of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington Surrey, GU9 7PT VT 05401-4405 England USA www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Renaissance food from Rabelais to Shakespeare: culinary readings and culinary histories. 1. Food habits - Europe - History - 16th century. 2. Food habits - Europe - History- 17th century. 3. Food habits in literature. 4. Diet in literature. 5. Cookery in literature. 6. Food writing - Europe - History 16th century. 7. Food writing - Europe - History 17th century. 8. European literature Renaissance, 1450-1600 - History and criticism. 9. European literature - 17th century - History and criticism. 1. Fitzpatrick, Joan. 809.9'33564'09031-dc22 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Renaissance food from Rabelais to Shakespeare: culinary readings and culinary histories I edited by Joan Fitzpatrick. p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7546-6427-7 (alk. paper) 1. European literature-Renaissance, l450-1600-History and criticism. 2. Food in literature. 3. Food habits in literature. -

Colonial Receipts

Foods & Feasts of Colonial Virginia Jamestown Settlement & American Revolution Museum at Yorktown November 28-30, 2019 & November 26-28, 2020 Colonial Receipts 17th-Century Recipes Period dishes prepared by historical interpreters in Jamestown Settlement’s outdoor re-creations of a Powhatan Indian village and 1610-14 English fort The Lord of Devonshire his Pudding Take manchet and slice it thin, then take dates the stones cut out, & cut in pieces, & reasins of the Sun the stones puld out, & a few currance, & marrow cut in pieces, then lay your sippets of bread in the bottome of your dish, then lay a laying of your fruit & mary on the top, then antoher laying of sippets of briad, so doo till your dish be full, then take crame & three eggs yolds & whites, & some Cynamon & nutmeg grated, & some sugar, beat it all well together, & pour in so much of it into the dish as it will drinke up, then set it into the oven & bake it. Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book, 1604 A blood pudding Take the blood of hog whilst it is warm, and steep it in a quart, or more, of great oatmeal grits, and at the end of three days with your hands take the greits out of the blood, and drain them clean; then put to those grits more than a quart of the best cream warmed on the fire; then take mother of thyme, parsley, spinach, succory, endive, sorrel, and strawberry leaves, of each a few chopped exceeding small, and mix them with the grits, and also a little fennel seed finely beaten; then add a little pepper, cloves and mace, salt, and great store of suet finely shred, and well beaten; then therewith fill your farmes, and boil them, as hath been before described. -

Staging Domesticity Household Work and English Identity in Early Modern Drama

Staging Domesticity Household Work and English Identity in Early Modern Drama Wendy Wall PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011±4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org ÿC Wendy Wall 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times 10/12 pt. System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Wall, Wendy, 1961± Staging domesticity: household work and English identity in Early Modern drama/ Wendy Wall. p. cm. ± (Cambridge studies in Renaissance literature and culture; 41) Includes bibliogriphical references and index. ISBN 0 521 80849 9 1. English drama ± Early modern and Elizabethan, 1500±1600 ± History and criticism. 2. English drama ± 17th century ± History and criticism. 3. Domestic drama, English ± History and criticism. 4. Housekeeping in literature. 5. Cookery in literature. 6. Women in literature. 7. Home in literature. -

Invention of the Modern Cookbook This Page Intentionally Left Blank Invention of the Modern Cookbook

Invention of the Modern Cookbook This page intentionally left blank Invention of the Modern Cookbook Sandra Sherman Copyright 2010 by Sandra Sherman All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sherman, Sandra. Invention of the modern cookbook / Sandra Sherman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59884-486-3 (hard copy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-59884-487-0 (ebook) 1. Cookery. 2. Cookery, British—History. 3. Food habits—Great Britain—History. 4. Cookery, American—History. 5. Food habits—United States—History. I. Title. TX652.S525 2010 641.5973—dc22 2010005736 ISBN: 978-1-59884-486-3 E-ISBN: 978-1-59884-487-0 141312111012345 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. Greenwood Press An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America The publisher has done its best to make sure the instructions and/or recipes in this book are consistent with their seventeenth- and eighteenth-century originals. How- ever, they are included mainly for illustrative purposes; users should apply judgment and experience when preparing recipes, especially parents and teachers working with young people. -

Documentation(Pdf)

To keep artichocks all the yeare. Take your artichocks & put them on the fire, in could water, let them boyle two walmes, to fifie you much take a quarter of a pound of allome, & a some small wort, & put into it then let it boyle, two walmes more, then take out the artichocks, & let them cole, then put into the licor two handfuls of nettles & boyle them in the licor, then straine it & let it stand till it be cold, then put it to the Artichocks, & in the putting in put a quart of veriuice to it, let them bee two or three dayes gathered afore you doe them & when you spend them, wash them in hot water, before you boyle them.1 From The Complete Receipt Book of Ladie Elynor Fetiplace, 1604 My Translation: Take your artichokes & put them on the fire, in cold water, let them boil two walmes, to 50 you take a quarter of a pound of alum, & some small wort & put into it then let it boil two walmes more, then take out the artichokes & let them cool, then put into the liquid two handfuls of nettles & boil them in the liquid, then strain it & let it stand till it be cold, then put into it the artichokes, & in the putting in put a quart of verjuice to it, let them be two or three days gathered before you do them & when you use them, wash them in hot water, before you boil them. My Recipe: Prepare your artichokes (clip off leaves, remove chokes). Place in cold water with a little acid/lemon juice to prevent discoloration. -

The Material Culture of Shakespeare's England

The Material Culture of Shakespeare’s England: a study of the early modern objects in the museum collection of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust by Peter Hewitt A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis investigates the material culture of early modern England as reflected in the object collections of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon. The collection consists of nearly 300 objects and six buildings dating from the period 1500-1650 representing ‗the life, work and times of William Shakespeare‘, with a particular emphasis on domestic and community life in Shakespeare‘s Stratford. Using approaches from museum studies and material culture studies together with historical research, this thesis demonstrates how objects add depth and complexity to historical and museological narratives, and presents a range of unique and never before examined material sources for the study of the social and cultural history of the period. -

To Make a Tarte of Cheese (From 'A Proper New

To Make a Tarte of Cheese (from ‘A Proper new booke of cokerye’ aka ‘Margaret Parker’s cookery book’ 1557) Take hard cheese and cut it into slices, and put it in fresh water or in sweet milk for three hours. Then take it out and break it up in a mortar until it is in small pieces. Strain through strainer with the yolks of five eggs, season with sugar and sweet butter, and bake To Make a Tarte of Prunes (from ‘The Good Housewife’s Jewel’ by Thomas Dawson 1597) Put your prunes into a pot, and put in red wine or claret wine, and a little faire water, and stirre them now and then, and when they be boiled enough, put them into a bowl, and straine them with sugar, cinnamon and ginger. Fygey or Figgy Pudding. (from ‘Forme of Cury’ the oldest collection of recipes in English c.1400) “Take Almande blanched; grynde hem and braw hem up with water and wyne; quarter figs, hole raisins. Cast perto powder ginger and hony clarified; seep it wel and salt it, and seve forth.” Half cup each of water, ground almonds, white wine (or Madeira if you want a richer taste) one cup of chopped, dried and stoned figs one cup whole raisins 2 tablespoons honey half tablespoon powdered ginger (fresh if you prefer a bit of a kick) quarter of a teaspoon of salt Mix the wine with the almonds over a medium heat until it becomes a paste. Mix in the rest of the liquid. Let the mixture combine further for a few minutes over a low heat then add the figs, raisins, honey, ginger, salt and bring to the boil, stirring all the time. -

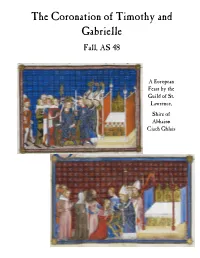

The Coronation of Timothy and Gabrielle Fall, AS 48

The Coronation of Timothy and Gabrielle Fall, AS 48 A European Feast by the Guild of St. Lawrence, Shire of Abhainn Ciach Ghlais The recipes for this feast were chosen by members of the St. Lawrence (cook’s) guild in July, August and September of 2013. Individuals who chose, adapted, redacted and test-cooked the recipe are noted after each recipe. As coordinators of the feast, I would like to thank everyone who generously donated their time and efforts over the last 3 months to cook these dishes, the countless ones we tried (and now have in our collective back pockets for future feasts) and to taste the fruits of our labors. Please feel free to contact us if you would like further information on anything in this recipe collection. Gille MacDhnouill Starters Bread & Butter, Eggplant pancakes, Roman peacock duck chicken sliders, Ein condimentlin (pickled vegetables), Ravioli the Lombardian way 1st course Roast pig w/ garlic sauce and mustard, Genovese tart, Sweet Potatoes with Rose Syrup Entrée Hypocras Jelly Fish Pies 2nd course: Meat tile, Mushrooms of the first night, Roman cabbage (broccoli), Savory toasted cheese A sweets sideboard with tarts, custards, flans, fresh and preserved fruits. Feast Menu, Fall Coronation, AS48 2 Starters Eggplant Isfîriyâ [eggplant pancakes] Cook peeled eggplants in water and salt until done. Take out of the water and grate them to bits in a dish, with grated bread crumbs, eggs, pepper, coriander, cinnamon, some murri naqî’ and oil. Beat all until combined, then fry [the batter into] thin breads [crepes or pancakes], following the instructions for making isfîriyya Simple Isfîriyâ Break however many eggs you like into a big plate and add some sourdough, dissolved with a commensurate number of eggs, and also pepper, coriander, saffron, cumin, and cinnamon. -

The Good Housewife's Receipt Book

THE GOOD HOUSEWIFE’S RECEIPT BOOK: GENDER IN THE EARLY-MODERN ENGLISH KITCHEN ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History ____________ © Scarlett O. Harris 2014 Spring 2014 THE GOOD HOUSEWIFE’S RECEIPT BOOK: GENDER IN THE EARLY-MODERN ENGLISH KITCHEN A Thesis by Scarlett O. Harris Spring 2014 APPROVED BY THE DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND VICE PROVOST FOR RESEARCH: _______________________________ Eun K. Park, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: ______________________________ Jason Nice, Ph.D., Chair ______________________________ Kate Transchel, Ph.D. ______________________________ Robert V. O’Brien, Ph.D. PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this thesis may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Publication Rights…………………………………………………………………... iii Abstract………………………………………………………………….………..…. v Introduction…………………………………………………………………………. 1 Female Reformation, The Demographic, Self-Sufficiency, Housewifery: Symbolic of the Lifecycle, Traditional Conservative Idealism, The Contemporary Sources, Historiography, Women’s Work, Women’s Worth CHAPTER I. Chapter I: Recipes……………………………………………….............. 38 Education and Literacy, Female Reading, Female Writing, Education in Housewifery, Female Networks, Male-authored Treatises, Receipt Books, Creativity and Experimentation, Spirituality -

'John Ince His Booke': a Previously Unrecorded Medical Text Of

‘John Ince His Booke’: A previously unrecorded medical text of the sixteenth century by Lesley Bernadette Maria Smith A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Volume One Text and Bibliography Department of the History of Medicine (Medicine, Ethics, Society, History) The University of Birmingham March 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ‘John Ince His Booke’: A previously unrecorded medical text of the sixteenth century by Lesley Bernadette Maria Smith A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Volume One Text and Bibliography Department of the History of Medicine (Medicine, Ethics, Society, History) The University of Birmingham March 2014 [i] ABSTRACT This thesis concerns a previously unpublished medical text, which takes the form of a manuscript note-book dating from the mid-sixteenth century. The original work is anonymous and untitled, but is known as the ‘Ince book’ after the later addition of the inscription ‘John Ince his Booke’ on the first page. The text contains 290 individual entries, all but a few of which are medical recipes. -

The Making of Domestic Medicine: Gender, Self-Help and Therapeutic Determination in Household Healthcare in South-West England in the Late Seventeenth Century

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Stobart, Anne (2008) The making of domestic medicine: gender, self-help and therapeutic determination in household healthcare in South-West England in the late seventeenth century. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/6745/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated.