The Material Culture of Shakespeare's England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Sauces Reconsidered

SAUCES RECONSIDERED Rowman & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy General Editor: Ken Albala, Professor of History, University of the Pacific ([email protected]) Rowman & Littlefield Executive Editor: Suzanne Staszak-Silva ([email protected]) Food studies is a vibrant and thriving field encompassing not only cooking and eating habits but also issues such as health, sustainability, food safety, and animal rights. Scholars in disciplines as diverse as history, anthropol- ogy, sociology, literature, and the arts focus on food. The mission of Row- man & Littlefield Studies in Food and Gastronomy is to publish the best in food scholarship, harnessing the energy, ideas, and creativity of a wide array of food writers today. This broad line of food-related titles will range from food history, interdisciplinary food studies monographs, general inter- est series, and popular trade titles to textbooks for students and budding chefs, scholarly cookbooks, and reference works. Appetites and Aspirations in Vietnam: Food and Drink in the Long Nine- teenth Century, by Erica J. Peters Three World Cuisines: Italian, Mexican, Chinese, by Ken Albala Food and Social Media: You Are What You Tweet, by Signe Rousseau Food and the Novel in Nineteenth-Century America, by Mark McWilliams Man Bites Dog: Hot Dog Culture in America, by Bruce Kraig and Patty Carroll A Year in Food and Beer: Recipes and Beer Pairings for Every Season, by Emily Baime and Darin Michaels Celebraciones Mexicanas: History, Traditions, and Recipes, by Andrea Law- son Gray and Adriana Almazán Lahl The Food Section: Newspaper Women and the Culinary Community, by Kimberly Wilmot Voss Small Batch: Pickles, Cheese, Chocolate, Spirits, and the Return of Artisanal Foods, by Suzanne Cope Food History Almanac: Over 1,300 Years of World Culinary History, Cul- ture, and Social Influence, by Janet Clarkson Cooking and Eating in Renaissance Italy: From Kitchen to Table, by Kath- erine A. -

Thomas Silkstede's Renaissance-Styled Canopied Woodwork in the South Transept of Winchester Cathedral

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 58, 2003, 209-225 (Hampshire Studies 2003) THOMAS SILKSTEDE'S RENAISSANCE-STYLED CANOPIED WOODWORK IN THE SOUTH TRANSEPT OF WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL By NICHOLAS RIALL ABSTRACT presbytery screen, carved in a renaissance style, and the mortuary chests that are placed upon it. In Winchester Cathedral is justly famed for its collection of another context, and alone, Silkstede's work renaissance works. While Silkstede's woodwork has previ might have attracted greater attention. This has ously been described, such studies have not taken full been compounded by the nineteenth century account of the whole piece, nor has account been taken of thealteration s to the woodwork, which has led some important connection to the recently published renaissancecommentator s to suggest that much of the work frieze at St Cross. 'The two sets ofwoodwork should be seen here dates to that period, rather than the earlier in the context of artistic developments in France in the earlysixteent h century Jervis 1976, 9 and see Biddle sixteenth century rather than connected to terracotta tombs1993 in , 260-3, and Morris 2000, 179-211). a renaissance style in East Anglia. SILKSTEDE'S RENAISSANCE FRIEZE INTRODUCTION Arranged along the south wall and part of the Bishop Fox's pelican everywhere marks the archi west wall of the south transept in Winchester tectural development of Winchester Cathedral in Cathedral is a set of wooden canopied stalls with the early sixteenth-century with, occasionally, a ref benches. The back of this woodwork is mosdy erence to the prior who held office for most of Fox's panelled in linenfold arranged in three tiers episcopate - Thomas Silkstede (prior 1498-1524). -

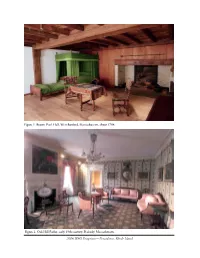

The Deinstallation of a Period Room: What Goes in to Taking One Out

Figure 1. Brown Pearl Hall, West Boxford, Massachusetts, about 1704. Figure 2. Oak Hill Parlor, early 19th century, Peabody, Massachusetts. 2006 WAG Postprints—Providence, Rhode Island The Deinstallation of a Period Room: What Goes in to Taking One Out Gordon Hanlon, Furniture and Frame Conservation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Melissa H. Carr, Masterwork Conservation ABSTRACT Many American museums installed period rooms in the early twentieth century. Eighty years later, different environmental standards and museum expansions mean that some of those rooms need to be removed and either reinstalled or placed in storage. Over the past four years the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston has deinstalled all of their European and American period rooms as part of a Master Plan to expand and reorganize the museum. The removal of the rooms was coordinated and supported by museum staff and performed by private contractors. The first part of this paper will discuss the background of the project and the particular issues of the museum to prepare for the deinstallation. The second part will provide an overview of the deinstallation of one specific, painted and fully-paneled room to illustrate the process. It will include comments on the planning, logistics, physical removal and documentation, as well as notes on its future reinstallation. Introduction he Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is in the process of implementing the first phase of a Master Plan which involves the demolition of the east wing of the museum and the building of a new American wing designed by the London-based architect Sir Norman Foster. This project required Tthat the museum’s eighteen period rooms (eleven American and seven European) and two large architec- tural doorways, on display in the east wing and a connector building, be deinstalled and stored during the construction phase. -

Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas. Lise Brandt Pedersen Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pedersen, Lise Brandt, "Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2159. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2159 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I 72- 17,797 PEDERSEN, Lise Brandt, 1926- SHAVIAN .SHAKESPEARE:' SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, XEROXA Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan tT,TITn ^TnoT.r.a.A'TTAItf U4C PPPM MT PROPTT.MF'n FVAOTT.V AR RECEI VE D SHAVIAN SHAKESPEARE: SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Lise Brandt Pedersen B.A., Tulane University, 1952 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1963 December, 1971 ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to thank Dr. -

Macbeth a Unit Plan

MACBETH A UNIT PLAN Second Edition Based on the play by William Shakespeare Written by Mary B. Collins Teacher's Pet Publications, Inc. 11504 Hammock Point Berlin, Maryland 21811 Copyright Teacher's Pet Publications, Inc. 1996, 1999 This LitPlan for William Shakespeare’s Macbeth has been brought to you by Teacher’s Pet Publications, Inc. Copyright Teacher’s Pet Publications 1999 11504 Hammock Point Berlin MD 21811 Only the student materials in this unit plan may be reproduced. Pages such as worksheets and study guides may be reproduced for use in the purchaser’s classroom. For any additional copyright questions, contact Teacher’s Pet Publications. TABLE OF CONTENTS - Macbeth Introduction 10 Unit Objectives 12 Reading Assignment Sheet 13 Unit Outline 14 Study Questions (Short Answer) 19 Quiz/Study Questions (Multiple Choice) 28 Pre-reading Vocabulary Worksheets 42 Lesson One (Introductory Lesson) 52 Nonfiction Assignment Sheet 55 Oral Reading Evaluation Form 59 Writing Assignment 1 61 Writing Assignment 2 67 Writing Assignment 3 78 Writing Evaluation Form 68 Vocabulary Review Activities 66 Extra Writing Assignments/Discussion ?s 71 Unit Review Activities 80 Unit Tests 82 Unit Resource Materials 123 Vocabulary Resource Materials 139 3 ABOUT THE AUTHOR WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE SHAKESPEARE, William (1564-1616). For more than 350 years, William Shakespeare has been the world's most popular playwright. On the stage, in the movies, and on television his plays are watched by vast audiences. People read his plays again and again for pleasure. Students reading his plays for the first time are delighted by what they find. Shakespeare's continued popularity is due to many things. -

The Case Against William of Stratford by Tony Pointon

de Vere Society newsletter October 2015 For the real biography of William Shakspere, see his life story by Richard Malim on the website deveresociety.co.uk The Case against William of Stratford By Tony Pointon There are many reasons to doubt that a man from Stratford wrote the works of Shakespeare. Here are twenty such arguments, prepared by Tony Pointon. Further details can be found in Professor Pointon’s book The Man Who Was Never SHAKESPEARE (Parapress 2011). Firstly, an important distinction: William Shakspere was a business man from Stratford William Shakespeare (or Shake- speare) was the name used by the author of the plays & poems 1. The Stratford man who is said to have written the plays poems was baptised as Shakspere in 1564 and buried as Shakspere in 1616, and never used the name ‘Shake-speare’ or ‘Shakespeare’ in his life. It is known that an actor-businessman of Stratford upon Avon was baptised in 1564 as William son of John Shakspere. He married as William Shaxpere, was buried as William Shakspere and had three children who were named as Susanna, Judith and Hamnet – all Shakspere. His family name was Shakspere and he never used the name ‘Shakespeare’. Similarly, the Elizabethan writer called ‘Shakespeare’ never used Shakspere. Legally, that’s good evidence they were two different men. 2. This man had two daughters, both baptised Shakspere, both illiterate. A writer’s children? deveresociety.co.uk 15 de Vere Society newsletter October 2015 Shakspere’s family through four generations were illiterate, except that his daughter Susanna learnt to write her first name – very poorly – when she wed the Stratford doctor, John Hall in 1607. -

Sources of Lear

Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Lynne Bradley, 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) Abstract The temptation to meddle with Shakespeare has proven irresistible to playwrights since the Restoration and has inspired some of the most reviled and most respected works of theatre. Nahum Tate’s tragic-comic King Lear (1681) was described as an execrable piece of dementation, but played on London stages for one hundred and fifty years. David Garrick was equally tempted to adapt King Lear in the eighteenth century, as were the burlesque playwrights of the nineteenth. In the twentieth century, the meddling continued with works like King Lear’s Wife (1913) by Gordon Bottomley and Dead Letters (1910) by Maurice Baring. -

Hall's Croft Garden Information Full Symbol Version

Hall's Croft Garden Information Full Symbol Version We hope everyone can enjoy their visit. Welcome to Hall's Croft Garden. www.shakespeare.org Widgit Symbols © Widgit Software 2002-2018. This resource was created with InPrint 3. Find out more at www.widgit.com Page - of 12 Garden There are herbs growing in the garden. John Hall used the herbs in his remedies. Shakespeare mentions the trees and flowers in his plays. The garden has changed since John and Susanna lived here. There was an area for flowers and herbs and a kitchen garden. There was also an orchard. Widgit Symbols © Widgit Software 2002-2018. This resource was created with InPrint 3. Find out more at www.widgit.com Page 1 of 12 Design The garden was designed in 1950 after the restoration of the house. The design is similar to gardens during Shakespeare's time. It also feels like a modern garden. There are lots of familiar plants. Mulberry Tree In the middle of the garden is the L-shaped Mulberry tree. The tree is about 300 years old and previously collapsed. Widgit Symbols © Widgit Software 2002-2018. This resource was created with InPrint 3. Find out more at www.widgit.com Page 2 of 12 Gardeners helped the tree. The tree was propped up with bricks. King James I planted mulberry trees in the UK for silk worms. Silk worms like the leaves of the Mulberry tree. Silk was a very expensive material. Mulberries turn red during summer. Mulberries were used in expensive drinks and desserts. Widgit Symbols © Widgit Software 2002-2018. -

Airstep Advantage® • Airstep Evolution® Airstep Plus® • Armorcoretm Pro UR • Armorcoretm Pro

® Featuring AirStep Advantage Sheet Flooring DREAMTM Economy Match: 27" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88080 Nap Time 88081 Free Fall 88082 Daybreak WONDERTM Economy Match: 6" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88050 Dandelion Puff 88054 Porpoise SAVORTM Economy Match: 54" L x 72" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88000 Clam Chowder 88001 Warm Croissant 88002 Cookies n’ Cream 88003 Pecan Pie 88004 Beluga Caviar 88005 Sushi 1 ® Featuring AirStep Advantage Sheet Flooring PLAYTIMETM Economy Match: Random L x 48" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88010 Hop Scotch 88011 Swing Set 88013 Hide and Seek 88014 Board Game 88015 Tree House TM REMINISCE CURIOUSTM Economy Match: 9" L x 48" W Do Not Reverse Sheets Economy Match: Random L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88060 First Snowfall 88061 Catching Fireflies 88062 Counting Stars 88041 Presents 88042 Magic Trick UNWINDTM Economy Match: 27" L x 13.09" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88030 Mountain Air 88031 Weekend in the 88032 Sunday Times 88033 Cup of Tea Country MYSTICTM Economy Match: 18" L x 16" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88070 Harp Strings 88071 Knight's Shadow 88072 Himalayan Trek 2 ® Featuring AirStep Evolution Sheet Flooring CASA NOVATM Economy Match: 27" L x 13.09" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72140 San Pedro Morning 72141 Desert View 72142 Cabana Gray 72143 La Paloma Shadows KALEIDOSCOPETM Economy Match: 18" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72150 Paris Rain 72151 Palisades Park 72152 Roxbury Caramel 72153 Fresco Urbain LIBERTY SQUARETM Economy Match: 18" L x 18" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72160 Blank Canvas 72161 Parkside Dunes -

Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff | the American Conservative

10/26/2017 Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff | The American Conservative BLOGS POLITICS WORLD CULTURE EVENTS NEW URBANISM ABOUT DONATE The Right’s Redeeming the Happy Birthday, I Fought a War How Saddam Ezra Pound, Shutting Up The Strangene Biggest Wedge Debauched Hillary Against Iran— Hussein Locked Away Richard Spencer of ‘Stranger Issue: Donald Falstaff and It Ended Predicted Things’ Trump Badly America’s Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff Do not moralize---there is a little of Shakespeare's 'Fat Knight' in all of us. By ALLEN MENDENHALL • October 26, 2017 Like 3 Share Tweet Falstaff und sein Page, by Adolf Schrödter, 1866 (Public Domain). Falstaff: Give Me Life (Shakespeare’s Personalities) Harold Bloom, Scribner, 176 pages. In The Daemon Knows, published in 2015, the heroic, boundless Harold Bloom claimed to have one more book left in him. If his contract with Simon & Schuster is any indication, he has more work than that to complete. The effusive 86-year-old has agreed to produce a sequence of five books on Shakespearean personalities, presumably those with whom he’s most enamored. The first, recently released, is Falstaff: Give Me Life, which has been called an “extended essay” but reads more like 21 ponderous essay-fragments, as though Bloom has compiled his notes and reflections over the years. The result is a solemn, exhilarating meditation on Sir John Falstaff, the cheerful, slovenly, degenerate knight whose unwavering and ultimately self- destructive loyalty to Henry of Monmouth, or Prince Hal, his companion in William Shakespeare’s Henry trilogy (“the Henriad”), redeems his otherwise debauched character. http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/redeeming-the-debauched-falstaff/ 1/4 10/26/2017 Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff | The American Conservative Except Bloom doesn’t see the punning, name-calling Falstaff that way. -

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: