The Deinstallation of a Period Room: What Goes in to Taking One Out

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Silkstede's Renaissance-Styled Canopied Woodwork in the South Transept of Winchester Cathedral

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 58, 2003, 209-225 (Hampshire Studies 2003) THOMAS SILKSTEDE'S RENAISSANCE-STYLED CANOPIED WOODWORK IN THE SOUTH TRANSEPT OF WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL By NICHOLAS RIALL ABSTRACT presbytery screen, carved in a renaissance style, and the mortuary chests that are placed upon it. In Winchester Cathedral is justly famed for its collection of another context, and alone, Silkstede's work renaissance works. While Silkstede's woodwork has previ might have attracted greater attention. This has ously been described, such studies have not taken full been compounded by the nineteenth century account of the whole piece, nor has account been taken of thealteration s to the woodwork, which has led some important connection to the recently published renaissancecommentator s to suggest that much of the work frieze at St Cross. 'The two sets ofwoodwork should be seen here dates to that period, rather than the earlier in the context of artistic developments in France in the earlysixteent h century Jervis 1976, 9 and see Biddle sixteenth century rather than connected to terracotta tombs1993 in , 260-3, and Morris 2000, 179-211). a renaissance style in East Anglia. SILKSTEDE'S RENAISSANCE FRIEZE INTRODUCTION Arranged along the south wall and part of the Bishop Fox's pelican everywhere marks the archi west wall of the south transept in Winchester tectural development of Winchester Cathedral in Cathedral is a set of wooden canopied stalls with the early sixteenth-century with, occasionally, a ref benches. The back of this woodwork is mosdy erence to the prior who held office for most of Fox's panelled in linenfold arranged in three tiers episcopate - Thomas Silkstede (prior 1498-1524). -

Airstep Advantage® • Airstep Evolution® Airstep Plus® • Armorcoretm Pro UR • Armorcoretm Pro

® Featuring AirStep Advantage Sheet Flooring DREAMTM Economy Match: 27" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88080 Nap Time 88081 Free Fall 88082 Daybreak WONDERTM Economy Match: 6" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88050 Dandelion Puff 88054 Porpoise SAVORTM Economy Match: 54" L x 72" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88000 Clam Chowder 88001 Warm Croissant 88002 Cookies n’ Cream 88003 Pecan Pie 88004 Beluga Caviar 88005 Sushi 1 ® Featuring AirStep Advantage Sheet Flooring PLAYTIMETM Economy Match: Random L x 48" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88010 Hop Scotch 88011 Swing Set 88013 Hide and Seek 88014 Board Game 88015 Tree House TM REMINISCE CURIOUSTM Economy Match: 9" L x 48" W Do Not Reverse Sheets Economy Match: Random L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88060 First Snowfall 88061 Catching Fireflies 88062 Counting Stars 88041 Presents 88042 Magic Trick UNWINDTM Economy Match: 27" L x 13.09" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88030 Mountain Air 88031 Weekend in the 88032 Sunday Times 88033 Cup of Tea Country MYSTICTM Economy Match: 18" L x 16" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88070 Harp Strings 88071 Knight's Shadow 88072 Himalayan Trek 2 ® Featuring AirStep Evolution Sheet Flooring CASA NOVATM Economy Match: 27" L x 13.09" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72140 San Pedro Morning 72141 Desert View 72142 Cabana Gray 72143 La Paloma Shadows KALEIDOSCOPETM Economy Match: 18" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72150 Paris Rain 72151 Palisades Park 72152 Roxbury Caramel 72153 Fresco Urbain LIBERTY SQUARETM Economy Match: 18" L x 18" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72160 Blank Canvas 72161 Parkside Dunes -

Cheating Is Fine When the Result Is a Beautiful Copy of an Early Oak Chest

Project Project PHOTOGRAPHS BY GMC/ANTHONY BAILEY early piece of furniture with linenfold detail, the stock thickness needs to be 25mm for the stiles and rails and about 16-18mm for the panels. The legs are made of two pieces of 25mm oak to give the required thickness. I reserved the ray-figured boards for the linenfold panels. To make construction easier treat each face of the chest as one complete item. The front and back and the lid comprise complete ‘units’, Wealden linenfold cutters and and the ends and bottom are fitted others used in the project afterwards. T&G cutters Router cutters used Wealden’s Shaker-style large tongue- in this project and-groove (T&G) cutter set allows Wealden Tool Co: linenfold set, large neat jointing and panelling without tongue and groove set, chamfer 1 1 having to resort to mortice and tenons. T916B ⁄4 shank, V-groove T128 ⁄4 1 A router table and a large router will be shank, hinge morticing T310 ⁄4 shank, 1 needed for this operation. panel trim T8018B ⁄2 shank, beaded 1 1 Calculation of component sizes is edge T2503B ⁄4 shank, T2504B ⁄2 all important. Mark the square face English oak selected and machined ready shank, classic panel guided T1622B 1 sides and edges of the components for use ⁄4 shank. when planing to size and work to these marks as a datum throughout the several trial joints first and mark the project to ensure flush joint faces. correct shim with a felt-tip pen so that All the components for the end and Cut the stock for the legs and stiles the right one is used. -

Product Guide

2PRODUCT 018 GUIDE 1 CONTENTS LUXURY SHEET FLOORING 3 AirStep Advantage® 5 AirStep Evolution® 8 AirStep Plus® 10 ArmorCoreTM LUXURY TILE AND PLANK FLOORING 13 DuraCeramic Dimensions® 15 DuraCeramic® Origins 18 Ovations® 19 Structure® 22 Impact® 23 Endurance® 24 Triversa® VINYL COMPOSITION TILE 27 Alternatives® TECHNICAL 28 Transitions PRODUCT INSTALLATION MANUALS 31 DuraCeramic Installation Accessories 33 QuikStik 35 Technical Reference Guide 44 Ultratec Installation Instructions 51 DuraCeramic Installation and Technical Guide 66 Timeless Installation 77 Triversa Installation 81 QuikStik UnderFlor Installation Instructions 83 UnderFlor® Installation and Product Specification Guide CARE AND MAINTENANCE 85 Consumer Flooring Guide 2 Featuring ® AirStep Advantage Sheet Flooring SERENETM Economy Match: Random L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88090 Light Breeze 88091 Summer Nap 88092 Sunbaked Dock 88093 Rocking Chair WONDERTM Economy Match: 6" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88050 Dandelion Puff 88054 Porpoise SAVORTM Economy Match: 54" L x 72" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88000 Clam Chowder 88001 Warm Croissant 88002 Cookies n’ Cream 88003 Pecan Pie 88004 Beluga Caviar 88005 Sushi 3 Featuring ® AirStep Advantage Sheet Flooring PLAYTIMETM Economy Match: Random L x 48" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88010 Hop Scotch 88011 Swing Set 88013 Hide and Seek 88014 Board Game 88015 Tree House REMINISCETM CURIOUSTM Economy Match: 9" L x 48" W Do Not Reverse Sheets Economy Match: Random L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88060 First Snowfall 88061 Catching Fireflies 88062 -

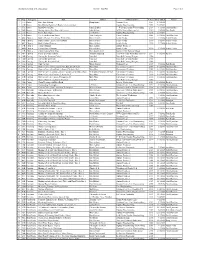

Sacramento County Maintained Road Index

SACRAMENTO COUNTY MAINTAINED ROAD INDEX STATE THOMAS BRD OF APRXMT ROAD FROM TO LENGTH MAP BROS MAINT ROAD REP SUP LENGTH NAME NUMBER ROAD NAME ROAD NAME MILES PAGE CO PAGE CO CODE R/W CODE YR DIST FEET 1ST AV 4F1106 GRAND AV ISLANDVIEW WY 0.280 06K25 01J 416 J7 40 M 96 5 1478 1ST AV 4F0170 SH160 GRAND AV 0.050 06K25 01J 397 A7 50 R 5 264 1ST PKWY 5C1380 SKY PKWY 2ND PKWY 0.140 07J31 10F 337 H1 MU 2 739 2ND AV 4F1105 SH160 WALNUT AV 0.190 06K25 01J 416 J7 50 M 5 1003 2ND PKWY 5C1379 SKY PKWY ALTAIR PKWY 0.150 07J31 10F 337 H1 MU 2 792 2ND ST 5A1135 U ST ASCOT ST 2.470 07J11 06D 257 G5 40 MU 1 13042 3RD AV 4F1104 WALNUT AV GRAND AV 0.140 06K25 01J 416 J7 50 MR 5 739 3RD PKWY 5C1369 5TH PKWY URSA PKWY 0.310 07J31 10F 337 H1 MU 2 1637 3RD ST 4E1113 BLAIR ST END 0.160 06J55 06J 376 J5 74 MR 5 845 4TH AV 5A1150 K ST 4TH AV 0.300 07J11 08E 257 H3 42 MU 62 1 1584 4TH AV 4F1111 SH160 ISLANDVIEW WY 0.210 06K25 01J 436 J1 Y 40 MR 96 5 1109 4TH PKWY 5C1375 SKY PKWY URANUS PKWY 0.160 07J41 01F 337 H1 MU 2 845 4TH ST 4E1112 BLAIR ST END 0.150 06J55 06J 377 A5 61 MR 5 792 4TH ST 5A1182 MARYSVILLE BL ASCOT ST 0.270 07J11 10E 257 H5 Y 60 MU 1 1426 5TH AV 5A1152 K ST SILVER CREST CIR 0.680 07J11 08E 257 H3 Y MU 88 1 3590 5THTH PKWY 5C1371C13 1 3RD PKWY ASTRON PKWY 0 0.260 260 0J31 07J3110F 33 337 J1 MU 2 137313 3 5TH ST 4E1111 BLAIR ST END 0.160 06J55 06J 377 A5 61 MR 5 845 5TH ST 5A1151 O ST K ST 0.500 07J11 08E 257 H3 51 MU 1 2640 6TH AV 5A1172 K ST L ST 0.120 07J11 08F 257 H3 Y 50 MU 1 634 6TH AV 5A1172 M ST N ST 0.120 07J11 07F 257 H2 Y 50 MU 1 634 -

Popular Woodworking Magazine April 2010 #182

Clark & Williams, Plane Makers BY CHRISTOPHER Sc HWARZ In an Arkansas basement, this somewhat unusual three-man company turns out extraordinary wooden handplanes. he married couple wanted a custom gazebo. So Larry Williams, a suc- T cessful carpenter, fetched his camera and was getting ready to photograph gazebos around town to show his clients. Right out- side his door, Williams took a wrong step, slipped on an ice patch and became a full- time toolmaker. Williams had broken an arm. To be more precise, he had ruined his arm and needed surgery and bone grafts. With one slip, his carpentry career disappeared. “No one needs a one-armed carpenter,” Williams says. “God I love carpentry. The kind of work I got to do … .” His voice trails off. Today Williams and his business partners, Bill Clark and Don McConnell, run Clark & Williams planemakers in Eureka Springs, Ark. This three-man business is one of the few in the Western world that makes traditional wooden-bodied planes. The company uses modern and traditional tools to make planes that represent, in their eyes, the pinnacle of tool development – 18th- century British moulding, bench and joinery planes. Planes of this era look simple – some Built for builders. Clark & Williams planes might appear simple, but they are actually extraordinarily woodworking authors have described tools refined tools that require machinery, hand tools and incredible skill to build. of this period as “primitive.” Yet once you see these planes through the eyes of their makers, later handplanes look and feel awkward. How long? Williams won’t even take a guess. -

Living with Early Oak Seventeenth-Century English Furniture Then and Now

Living with Early Oak Living with Early Oak Seventeenth-Century English Furniture Then and Now John Fiske and Lisa Freeman THE BELMONT PRESS BELMONT, VERMONT To Matthew Fiske 1970-2003 Too short a life, dammit. © 2005 John Fiske and Lisa Freeman. All rights reserved. ISBN: 0-9754569-0-3 The Belmont Press PO Box 270 Belmont, Vermont 05730 802.259.2579 802.259.3065 fax [email protected] www.fiskeandfreeman.com Contents List of Sidebars vii Timeline ix Preface xiii Part I: When Antiques Were New Chapter 1: Culture and Lifestyle 3 Chapter 2: The Guild System 22 Chapter 3: Decoration and Style 37 Part II: Forms and Functions Chapter 4: Storage 61 Boxes 61 Coffers 65 Chests of Drawers 68 Press Cupboards 74 Food Storage 79 Chapter 5: Seating 87 Joint Stools 87 Wainscot Chairs 90 Backstools 96 Benches or Forms 103 Settles 105 Turner’s Chairs 110 Chapter 6: Tables 117 Long 117 Gate-leg 122 Small 125 Chapter 7: Serving and Display 134 Court Cupboards 134 Low Dressers 141 Chapter 8: Beds 149 Tester 153 Half-headed 157 Truckle 157 v vi LIVING WITH EARLY OAK Part III: An Owner’s Handbook Chapter 9: Restoration and Repairs 165 Chapter 10: The Victorian Goths 175 Chapter 11: Provenance and Patina 183 Chapter 12: Care, Maintenance and Investment 187 Glossary References Index Sidebars Elizabethan Houses 7 Dining (and Living) in the Hall 12 Trees and People 26 A Turner’s Mural Cupboard 31 Caryatids 40 A Late Seventeenth-Century Mannerist Cupboard 43 Panels 44 A Tale of Two Boxes and One Maker 52 A Vernacular Masterwork 56 A Sophisticated Masterwork 57 The Survival Factor 73 Close Stools 90 “The Curious and Ingenious Art and Mystery of Japaning” 98 A Farmhouse Winged Armchair 104 Samuel Pepys Throws a Dinner Party 124 A National Style 142 Beds Royal and Humble 151 Bedding and Bed Chambers I 152 Bedding and Bed Chambers II 153 Bedding the Great Bed 155 Reflection 160 To Buy or Not to Buy, that is the Question 168 Fashionable Gothic 176 Patina and Preference 185 vii Timeline All timelines risk implying a false precision to the beginnings and endings of cul- tural trends. -

Carving Newsletter October 2020

CARVING NEWSLETTER OCTOBER 2020 The Portland area carving community is very diverse. We’re exploring the nooks and crannies over time to help us all appreciate what others are doing. This newsletter is intended for the Carving SIG of the Guild of Oregon Woodworkers, the Western Woodcarvers Association (WWA), our neighboring partner clubs and for unafiliated carvers, suppliers and instructors everywhere. The Oregon Carvers Guild is emerging as the successor to the WWA and building on the best parts of its 47 year history. This is a work in process. This month we finalized the logo, started building the web site, registered the domain names, and started adding content. We will be ready to launch by Christmas. The current look and feel are shown below. The web address will be “oregoncarvers.org". Our free monthly programs on Zoom have been popular. See the next page for the November topic on carving tools, and please register in order to get the Zoom link. Larry Wade, President On behalf of the Board Roger Crooks, Vice President Jerry Boone, Treasurer Terry Burnside, Secretary Note: underscored words are live links PAGE 1 UPCOMINGCARVING NEWSLETTER PROGRAMS OCTOBER 2020 FREE THE CARVING TOOLS OF GIL DRAKE - NOV 10TH, 7:00 PM Click here to register online or click here to request a Zoom link to be emailed. Drake Knives creates some of the most loved carving tools on the planet. Based near Seattle, they are famous for quality and a lifetime sharpening guarantee. Owners Gil Drake and his wife Bonnie will give us an insider’s tour of their manufacturing process. -

Spreadsheet Alpha Librarian Updated 04-25-18 Ver. 1

Woodworkers' Guild of Georgia Library 5/31/18 5:30 PM Page 1 of 3 # Page Category Title Author Additional Info © Year Date added Donor 1 11A Boxes Basic Box Making Doug Stowe Taunton Press 2007 1/12/2012 2 11D Boxes Box Making Bonanza (3 Books) check condition Popular Woodworking 2008 3/19/2012 3 57A Boxes Inlaid Dovetail Box Chuck Bender F+W Media Popular Woodworking 2014 4/1/2018 Guild purchase 4 04D Boxes Making Shaker Oval Boxes & Carriers John Wilson WWG Library Master on File 1987 7/8/2012 Tom Risoli 5 11C Boxes Puzzle Box Magic Jeff Vollmer Popular Woodworking 2010 3/19/2012 6 51D Boxes The Art of Bandsaw Boxes Alex Snodgrass Carter Products 2008 6/13/2016 Guild Purchase 7 40A Cabinets Build a Custom Face Frame Cabinet Box Robert Settich Settich Media 2010 3/9/2014 Settich Media 8 40B Cabinets Build Custom Cabinet Cabinet Doors Robert Settich Settich Media 2010 3/9/2014 Settich Media 9 40C Cabinets Build Custom Drawers Robert Settich Settich Media 2010 3/9/2014 Settich Media 10 14B Cabinets Cabinet Making Marc Adams Author Produced 11 40D Cabinets Cabinet Parts Calculator Robert Settich Settich Media 2010 3/9/2014 Settich Media 12 22B Cabinets Cabinetmaking Made Easy Marc Sommerfeld Sommerfeld's Tools for Wood 13 30C Cabinets Frame-and-Panel Cabinet Timothy Rousseau Fine WW Video Workshop Series #8 2011 1/14/2013 Rockler 14 16B Carving Carving the European Corbel Nora Hall Nora Hall Carving Designs 2006 15 16D Carving Carving the Linenfold Nora Hall Nora Hall Carving Designs 2006 16 16A Carving Carving the Newport Shell Nora Hall -

TUDOR FURNITURE from the MARY ROSE David Knell

TUDOR FURNITURE FROM THE MARY ROSE David Knell The warship Mary Rose was built at Portsmouth in 150 9-10 as part of a major programme to strengthen the English navy and improve coastal defences as a means of safeguarding merchant ships using the Channel. On 19 July 1545, nine years after she had been partially rebuilt and refitted, the Mary Rose sank at Spithead, off Portsmouth, during a defensive skirmish with a large French fleet intending to invade England. As she was hoisting sail and going about to assist the Henry Grace a Dieti, the English flagship, the Mary Rose suddenly heeled and it seems that the weight of the water pouring through her open gunports made the list irreversible and, inevitably, fatal.1 The ship descended rapidly to the seabed, where she lay heeled at 60 degrees from the vertical with the port side uppermost. By the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century the exposed port side and upper structures, weakened by biological attack and eroded by the abrasive currents, had collapsed and a hard layer of shelly clay had formed over the remaining silt-filled starboard side, protecting it and its contents beneath the seabed.2 The lack of oxygen under this layer decelerated the microbiological degradation of the concealed part of the ship and many organic materials have been surprisingly well preserved. Unfortunately, iron — particularly wrought iron — has not fared as well and, with the exception of guns, has for the most part corroded away leaving only residual traces. The wreck of the Mary Rose was rediscovered in 1971 and, after eleven years of arduous and meticulous excavation, the remains of the hull were raised and are now housed at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard. -

May 2017 the Work of Gehard Demetz

May 2017 The Work of Gehard Demetz LAST MONTH I promised more from carver Gehard Demetz. The following text is from his website: http://www.geharddemetz.com/writing.html : In just a few years, Gehard Demetz has risen to international prominence by applying his incredible craftsmanship as a traditional woodcarver to subjects that are new and appealing to contemporary viewers. His sculptures of children are at the same time attractive and disquieting and rendered with an amazing perfection that is by no means rhetorical or classical. One of the most startling technical features is the construction using small woodblocks and juxtaposing finely polished parts to very rough and sketchy surfaces. This particular construction and treatment render his sculptures absolutely unique in the domain of contemporary wood sculpture and is partly responsible for the great curiosity aroused by the appearance of his work in the art world. Since his debut in 2005, Gehard Demetz has been invited by prominent galleries to exhibit in the United States, Spain, Germany, Korea. He has also produced monumental sculptures on commission for collectors around the world. His sculptures feature wood blocks glued together leaving gaps and then carved, but with key features (such as faces) with no such holes. Surreal, gloomy-looking children pepper his work. I Feel (sic) My Mouth with Snow, 2010 I Forgot what My Father Said, My Shadow Can Walk on Its Warmer Now, 2011 2009 Water, 2012 Wood Archivist Check out this website: http://woodarchivist.com/category/wood-carving-patterns-and-techniques/. It includes a fantastic range of wood carving resources including tutorials. -

Berkshiretm Cast Iron Gas Stove

BerkshireTM Cast Iron Gas Stove 9 The Berkshire is shown in the Oxford Brown porcelain enamel finish. Enhancements include the Brick Fireback, Linenfold side and top panels, and painted flue pipe. Maximum BTU Minimum BTU Heating Capacity* Steady State Efficiency Canadian P.4.1 Input per Hour Input per Hour Up to 1,500 sq. ft. Up to 81.5% NG Efficiency 31,000 (NG & LP) 10,700 (NG) 12,600 (LP) with fan 81% LP Up to 72.9% NG - 73.1% LP *Heating capacity may vary depending on degree of home insulation, floor plan, ceiling height and the ambient temperature zone in which you live. Contact local building or fire officials about restrictions and installation requirements in your area. 10 The Berkshire is shown above in the New Iron painted finish. The Brick Fireback completes the unit. Think of the Berkshire as a functional work of art. Its classical balance and symmetry resembles a piece of fine furniture. This solidly built stove features decorative cast iron on the outside with a heavy-gauge unibody steel firebox for added durability. Design details include a large viewing area (18 inches wide by 12 inches high), and your choice of raised Linenfold side panels with delicate moldings or beautiful stone accents typical of early American architectural style. It’s no wonder the Berkshire is the best selling cast iron gas stove in America. Aromatherapy Tray Lopi is the only company that gives you the option of adding a hidden Aromatherapy Tray to your stove. Aromatherapy soothes the spirit, invigorates the mind and relaxes the body.