TUDOR FURNITURE from the MARY ROSE David Knell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary Rose Trust 2013 Annual Report

Annual Review 2013 Learning Conservation Heritage Mary Rose Annual Review 2013_v11.indd 1 20/06/2013 15:49 2 www.maryrose.org Annual Review 2013 Mary Rose Annual Review 2013_v11.indd 2 20/06/2013 15:49 Annual Review 2013 www.maryrose.org 3 Mary Rose Annual Review 2013_v11.indd 3 20/06/2013 15:49 4 www.maryrose.org Annual Review 2013 Mary Rose Annual Review 2013_v11.indd 4 20/06/2013 15:50 Chairman & Chief Executive Foreword This last year has been momentous for the Mary Rose Trust, In tandem with this, much research is opening up to the Trust and the achievements have been of national and international and is now higher in our priorities. The human remains, importance. The Mary Rose Project has been an exemplar now boldly explained more fully in our exhibition, can be of both excavation and conservation over its thirty plus year studied scientifically for the secrets they can reveal. Medical history, but experts from afar now declare the new museum research is included within our ambitions and we will be to be the exemplar of exhibition for future generations. New working with leading universities in this area. Similarly, standards have been set, and the success of our ambition has our Head of Collections is already involved in pioneering been confirmed by the early comments being received. work in new forms of conservation techniques, which could revolutionise the affordability and timescales of future Elsewhere in this review you will read more about the projects. These are just two examples of a number of areas challenges that were met in reaching this point. -

Surgery at Sea: an Analysis of Shipboard Medical Practitioners and Their Instrumentation

Surgery at Sea: An Analysis of Shipboard Medical Practitioners and Their Instrumentation By Robin P. Croskery Howard April, 2016 Director of Thesis: Dr. Lynn Harris Major Department: Maritime Studies, History Abstract: Shipboard life has long been of interest to maritime history and archaeology researchers. Historical research into maritime medical practices, however, rarely uses archaeological data to support its claims. The primary objective of this thesis is to incorporate data sets from the medical assemblages of two shipwreck sites and one museum along with historical data into a comparative analysis. Using the methods of material culture theory and pattern recognition, this thesis will explore changes in western maritime medical practices as compared to land-based practices over time. Surgery at Sea: An Analysis of Shipboard Medical Practitioners and Their Instrumentation FIGURE I. Cautery of a wound or ulcer. (Gersdorff 1517.) A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History Program in Maritime Studies East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Maritime Studies By Robin P. Croskery Howard 2016 © Copyright 2016 Robin P. Croskery Howard Surgery at Sea: An Analysis of Shipboard Medical Practitioners and Their Instrumentation Approved by: COMMITTEE CHAIR ___________________________________ Lynn Harris (Ph.D.) COMMITTEE MEMBER ____________________________________ Angela Thompson (Ph.D.) COMMITTEE MEMBER ____________________________________ Jason Raupp (Ph.D.) COMMITTEE MEMBER ____________________________________ Linda Carnes-McNaughton (Ph.D.) DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CHAIR ____________________________________ Christopher Oakley (Ph.D.) GRADUATE SCHOOL DEAN ____________________________________ Paul J. Gemperline (Ph.D.) Special Thanks I would like to thank my husband, Bernard, and my family for their love, support, and patience during this process. -

Post-Medieval Seafaring Anthropology 629

Spring, 2013 Post-Medieval Seafaring Anthropology 629 Instructor: Dr. Kevin Crisman The Office in Exile: 138 Read Building (Kyle Field Basement), ☎ 979-845-6696 Office hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 1-4 or by appointment This course examines archaeological and historical sources to chronicle and explore the development of shipbuilding, seafaring practices, world exploration, waterborne trade and economic systems, and naval warfare in Europe and around the world (except the Americas) from the fifteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century. Archaeological studies of shipwrecks, ships’ equipment, and cargoes provide a focal point for investigating change and continuity in the maritime sphere over five centuries. Prerequisites: Anth 615 and 616 or instructor approval. Course Schedule: Week 1. Introduction to Course. (Jan. 15) 1. Review of course goals and discussion of seminar presentations. 2. Discussion of term paper research, writing, and editing. 3. Europe at the End of the Medieval Era [Crisman]. Week 2. Transitions in the Technology of Ships and Weaponry. (Jan. 22) Seminar topics: 1. A peek at 15th-Century Shipping: the Aveiro A Wreck and the Newport Ship. 2. The Villefranche Wreck. 3. A 16th-Century Trio: Cattewater, Studland Bay, and ‘Kravel’ Wrecks. 4. Gunpowder Weapons in Late Medieval Europe [Crisman]. 2 Week 3. The Naval Revolution Incarnate: Henry VIII’s Mary Rose. (Jan. 29) Seminar topics: 1. Mary Rose: History and Construction Features. 2. Early 16th Century Ship Rigs and the Rigging of Mary Rose. 3. The Cannon and Small Arms of Mary Rose. 4. Shipboard Organization and Life on Mary Rose as Revealed by the Artifacts. -

Thomas Silkstede's Renaissance-Styled Canopied Woodwork in the South Transept of Winchester Cathedral

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 58, 2003, 209-225 (Hampshire Studies 2003) THOMAS SILKSTEDE'S RENAISSANCE-STYLED CANOPIED WOODWORK IN THE SOUTH TRANSEPT OF WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL By NICHOLAS RIALL ABSTRACT presbytery screen, carved in a renaissance style, and the mortuary chests that are placed upon it. In Winchester Cathedral is justly famed for its collection of another context, and alone, Silkstede's work renaissance works. While Silkstede's woodwork has previ might have attracted greater attention. This has ously been described, such studies have not taken full been compounded by the nineteenth century account of the whole piece, nor has account been taken of thealteration s to the woodwork, which has led some important connection to the recently published renaissancecommentator s to suggest that much of the work frieze at St Cross. 'The two sets ofwoodwork should be seen here dates to that period, rather than the earlier in the context of artistic developments in France in the earlysixteent h century Jervis 1976, 9 and see Biddle sixteenth century rather than connected to terracotta tombs1993 in , 260-3, and Morris 2000, 179-211). a renaissance style in East Anglia. SILKSTEDE'S RENAISSANCE FRIEZE INTRODUCTION Arranged along the south wall and part of the Bishop Fox's pelican everywhere marks the archi west wall of the south transept in Winchester tectural development of Winchester Cathedral in Cathedral is a set of wooden canopied stalls with the early sixteenth-century with, occasionally, a ref benches. The back of this woodwork is mosdy erence to the prior who held office for most of Fox's panelled in linenfold arranged in three tiers episcopate - Thomas Silkstede (prior 1498-1524). -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS Frank Broeze (ed.). Maritime History at the more importantly for the future of maritime Crossroads: A Critical Review of Recent Histori• history (and its funding), this literature has made ography. "Research in Maritime History," No. 9; little impact on main stream historiography. Not St. John's, NF: International Maritime Economic only in The Netherlands or in Denmark but History Association, 1995. xxi + 294 pp. US $15 virtually everywhere (with the possible exception (free to members of the IMEHA), paper; ISBN 0- of Great Britain), maritime history is on the 9695885-8-5. periphery of historical scholarship. Of all the national historiographies surveyed This collection of thirteen essays sets out to pro• in this volume, perhaps Canada's has had the most vide a review of the recent literature in maritime spectacular growth in the last twenty years. Most history. The inspiration for the compendium grew of this work has been as a result of the research out of the "New Directions in Maritime History" done by the Atlantic Canada Shipping Project at conference held at Fremantle, Western Australia Memorial University in St. John's. Canadian in 1993. Included in the collection are historio• maritime history scarcely existed before the graphies for eleven countries (or portions there• advent of the project. But while the nineteenth- of): Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Ger• century shipping of Atlantic Canada has been many, Greece, India, The Netherlands, the Otto• analyzed, much remains to be done. Work has man Empire, Spain, and the United States. One only begun on twentieth century topics (naval essay deals with South America, another concerns history excepted). -

The Deinstallation of a Period Room: What Goes in to Taking One Out

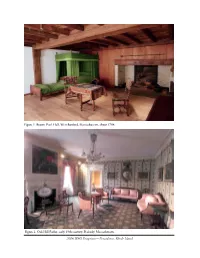

Figure 1. Brown Pearl Hall, West Boxford, Massachusetts, about 1704. Figure 2. Oak Hill Parlor, early 19th century, Peabody, Massachusetts. 2006 WAG Postprints—Providence, Rhode Island The Deinstallation of a Period Room: What Goes in to Taking One Out Gordon Hanlon, Furniture and Frame Conservation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Melissa H. Carr, Masterwork Conservation ABSTRACT Many American museums installed period rooms in the early twentieth century. Eighty years later, different environmental standards and museum expansions mean that some of those rooms need to be removed and either reinstalled or placed in storage. Over the past four years the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston has deinstalled all of their European and American period rooms as part of a Master Plan to expand and reorganize the museum. The removal of the rooms was coordinated and supported by museum staff and performed by private contractors. The first part of this paper will discuss the background of the project and the particular issues of the museum to prepare for the deinstallation. The second part will provide an overview of the deinstallation of one specific, painted and fully-paneled room to illustrate the process. It will include comments on the planning, logistics, physical removal and documentation, as well as notes on its future reinstallation. Introduction he Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is in the process of implementing the first phase of a Master Plan which involves the demolition of the east wing of the museum and the building of a new American wing designed by the London-based architect Sir Norman Foster. This project required Tthat the museum’s eighteen period rooms (eleven American and seven European) and two large architec- tural doorways, on display in the east wing and a connector building, be deinstalled and stored during the construction phase. -

Slipping Through The

Contents Acknowledgements 2 Executive Summary 3 Section 1: Introduction 4 1.1 Statement of IFA MAG Position 4 1.1.1 Archaeological Archives 4 1.1.2 Maritime Archaeological Archives 5 1.2 Structure of Strategy Document 6 1.3 Case Study: An Illustration of the Current Situation 7 Section 2: The Current System 9 2.1 The Current System in Policy: Roles and Responsibilities 9 2.1.1 Who’s Who? 9 2.1.2 Roles and Responsibilities 11 2.1.3 Legislative Responsibilities 12 2.2 The Current System in Practice 13 2.2.1 The Varied Fate of Protected Wreck Site Archives 13 2.2.2.The Unprotected Majority of Britain’s Historic Wreck Sites 15 2.3 A question of resources, remit or regulation? 16 Section 3: Archival Best Practice and Maritime Issues 17 3.1 Established Archival Policy and Best Practice 17 3.2 Application to Maritime Archives 18 3.2.1 Creation—Management and Standards 18 3.2.2 Preparation—Conservation, Selection and Retention 19 3.2.3 Transfer—Ownership and Receiving Museums 20 3.2.4 Curation—Access, Security and Public Ownership 21 3.3 Communication and Dialogue 22 3.4 Policy and Guidance Voids 23 Section 4: Summary of Issues 24 4.1.1 Priority Issues 24 4.1.2 Short Term Issues 24 4.1.3 Long Term Issues 24 4.2 Conclusions 25 Section 5: References 26 Section 6: Stakeholder and Other Relevant Organisations 27 Section 7: Policy Statements 30 IFA Strategy Document: Maritime Archaeological Archives 1 Acknowledgements This document has been written by Jesse Ransley and edited by Julie Satchell on behalf of the Institute of Field Archaeologists Maritime Affairs Group. -

Airstep Advantage® • Airstep Evolution® Airstep Plus® • Armorcoretm Pro UR • Armorcoretm Pro

® Featuring AirStep Advantage Sheet Flooring DREAMTM Economy Match: 27" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88080 Nap Time 88081 Free Fall 88082 Daybreak WONDERTM Economy Match: 6" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88050 Dandelion Puff 88054 Porpoise SAVORTM Economy Match: 54" L x 72" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88000 Clam Chowder 88001 Warm Croissant 88002 Cookies n’ Cream 88003 Pecan Pie 88004 Beluga Caviar 88005 Sushi 1 ® Featuring AirStep Advantage Sheet Flooring PLAYTIMETM Economy Match: Random L x 48" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88010 Hop Scotch 88011 Swing Set 88013 Hide and Seek 88014 Board Game 88015 Tree House TM REMINISCE CURIOUSTM Economy Match: 9" L x 48" W Do Not Reverse Sheets Economy Match: Random L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88060 First Snowfall 88061 Catching Fireflies 88062 Counting Stars 88041 Presents 88042 Magic Trick UNWINDTM Economy Match: 27" L x 13.09" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88030 Mountain Air 88031 Weekend in the 88032 Sunday Times 88033 Cup of Tea Country MYSTICTM Economy Match: 18" L x 16" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 88070 Harp Strings 88071 Knight's Shadow 88072 Himalayan Trek 2 ® Featuring AirStep Evolution Sheet Flooring CASA NOVATM Economy Match: 27" L x 13.09" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72140 San Pedro Morning 72141 Desert View 72142 Cabana Gray 72143 La Paloma Shadows KALEIDOSCOPETM Economy Match: 18" L x 36" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72150 Paris Rain 72151 Palisades Park 72152 Roxbury Caramel 72153 Fresco Urbain LIBERTY SQUARETM Economy Match: 18" L x 18" W Do Not Reverse Sheets 72160 Blank Canvas 72161 Parkside Dunes -

Marriage Certificates

GROOM LAST NAME GROOM FIRST NAME BRIDE LAST NAME BRIDE FIRST NAME DATE PLACE Abbott Calvin Smerdon Dalkey Irene Mae Davies 8/22/1926 Batavia Abbott George William Winslow Genevieve M. 4/6/1920Alabama Abbotte Consalato Debale Angeline 10/01/192 Batavia Abell John P. Gilfillaus(?) Eleanor Rose 6/4/1928South Byron Abrahamson Henry Paul Fullerton Juanita Blanche 10/1/1931 Batavia Abrams Albert Skye Berusha 4/17/1916Akron, Erie Co. Acheson Harry Queal Margaret Laura 7/21/1933Batavia Acheson Herbert Robert Mcarthy Lydia Elizabeth 8/22/1934 Batavia Acker Clarence Merton Lathrop Fannie Irene 3/23/1929East Bethany Acker George Joseph Fulbrook Dorothy Elizabeth 5/4/1935 Batavia Ackerman Charles Marshall Brumsted Isabel Sara 9/7/1917 Batavia Ackerson Elmer Schwartz Elizabeth M. 2/26/1908Le Roy Ackerson Glen D. Mills Marjorie E. 02/06/1913 Oakfield Ackerson Raymond George Sherman Eleanora E. Amelia 10/25/1927 Batavia Ackert Daniel H. Fisher Catherine M. 08/08/1916 Oakfield Ackley Irving Amos Reid Elizabeth Helen 03/17/1926 Le Roy Acquisto Paul V. Happ Elsie L. 8/27/1925Niagara Falls, Niagara Co. Acton Robert Edward Derr Faith Emma 6/14/1913Brockport, Monroe Co. Adamowicz Ian Kizewicz Joseta 5/14/1917Batavia Adams Charles F. Morton Blanche C. 4/30/1908Le Roy Adams Edward Vice Jane 4/20/1908Batavia Adams Edward Albert Considine Mary 4/6/1920Batavia Adams Elmer Burrows Elsie M. 6/6/1911East Pembroke Adams Frank Leslie Miller Myrtle M. 02/22/1922 Brockport, Monroe Co. Adams George Lester Rebman Florence Evelyn 10/21/1926 Corfu Adams John Benjamin Ford Ada Edith 5/19/1920Batavia Adams Joseph Lawrence Fulton Mary Isabel 5/21/1927Batavia Adams Lawrence Leonard Boyd Amy Lillian 03/02/1918 Le Roy Adams Newton B. -

International Marine Archaeological & Shipwreck Society 2 1 3 4 5 7 6

International Marine Archaeological & Shipwreck Society 1 Newsletter Number 6 September 2012 2 3 4 5 6 8 7 Included in this issue Oldest shipwreck on Scilly? Odyssey loses Treasure 9 Spanish man o'war MMO moves to clarify position Terra Nova found Sleeping Bear Dunes £2billion treasure Titanic artefacts IMASS Newsletter Number 6 Table of contents Page 2 Chairman's Report Page4 Adopt a Wreck Awards Page23 President’s/Editor Comments Page5 Medieval Fishing village Page23 One of Two Hospital Ships Page7 Mesolithic artefacts Page24 Oldest shipwreck on Scilly? Page12 Mary Rose studied. Page24 Odyssey loses Treasure Page13 North Sea warship wrecks Page24 HM. man o'war “Victory” Page14 EH names wreck sites Page25 MMO moves to clarify position Page15 Divers convicted of theft Page25 Duke of Edinburgh Award Page16 Should shipwrecks be left ? Page26 WW2 tanks studied Page17 SWMAG could be “Angels” Page27 LCT- 427 Page17 Shipwreck identified Page28 Technical divers find wreck Page18 Multibeam Sonar Page28 The 'Purton Hulks' Page18 Tunbridge Wells Sub Aqua Page28 Plymouth wreck artefacts Page19 “MAST” Charity swim Page29 Terra Nova found Page29 HMS Victory Page19 Antoinette survey Page21 Panama scuttled wrecks Page30 Heritage Database Page21 Baltic Sea Wreck find Page30 Bronze Age ship Page22 SS Gairsoppa wreck Page31 Newport medieval shipwreck Page22 Captain Morgan's cannon Page32 Ardnamurchan Viking Page22 Claim to a shipwreck Page32 King Khufu's 2nd ship Page32 IMASS Officers & Committee Members: Apollon Temple cargo Page32 President - Richard Larn OBE Sleeping Bear Dunes Page32 Vice Presidents - Alan Bax & Peter McBride Chairman - Neville Oldham Woods Hole Oceanographic Page33 Vice Chairman - Allen Murray Secretary - Steve Roue Wrecks off the Tuscan Page33 Treasurer & Conference booking secretary - Nick Nutt First US submarine Page33 Conference Ticket Secretary - Paul Dart Technical advisor & Speaker Advisor/Finder - Peter Holt Titanic wreck Page33 NAS. -

Cheating Is Fine When the Result Is a Beautiful Copy of an Early Oak Chest

Project Project PHOTOGRAPHS BY GMC/ANTHONY BAILEY early piece of furniture with linenfold detail, the stock thickness needs to be 25mm for the stiles and rails and about 16-18mm for the panels. The legs are made of two pieces of 25mm oak to give the required thickness. I reserved the ray-figured boards for the linenfold panels. To make construction easier treat each face of the chest as one complete item. The front and back and the lid comprise complete ‘units’, Wealden linenfold cutters and and the ends and bottom are fitted others used in the project afterwards. T&G cutters Router cutters used Wealden’s Shaker-style large tongue- in this project and-groove (T&G) cutter set allows Wealden Tool Co: linenfold set, large neat jointing and panelling without tongue and groove set, chamfer 1 1 having to resort to mortice and tenons. T916B ⁄4 shank, V-groove T128 ⁄4 1 A router table and a large router will be shank, hinge morticing T310 ⁄4 shank, 1 needed for this operation. panel trim T8018B ⁄2 shank, beaded 1 1 Calculation of component sizes is edge T2503B ⁄4 shank, T2504B ⁄2 all important. Mark the square face English oak selected and machined ready shank, classic panel guided T1622B 1 sides and edges of the components for use ⁄4 shank. when planing to size and work to these marks as a datum throughout the several trial joints first and mark the project to ensure flush joint faces. correct shim with a felt-tip pen so that All the components for the end and Cut the stock for the legs and stiles the right one is used. -

Sonardyne Fusion Acoustic Positioning System Used on the Mary Rose Excavation 2003

The Sonardyne Fusion Acoustic Positioning System used on the Mary Rose Excavation 2003 Peter Holt Sonardyne International Ltd August 2003 Fusion APS used on Mary Rose Excavation 2003 Introduction The Ministry of Defence may need to widen and straighten the channel approach to Portsmouth Harbour to accommodate their new aircraft carriers. The dredging work could affect the site of the Mary Rose historic wreck so what remains on the site had to be removed. When the hull of the Mary Rose was recovered from the seabed some of the ship was not recovered, some timbers and artefacts were reburied while the remains of the bow castle were never investigated. A multi-phase project was put together by the Mary Rose Trust with the aim of recovering the buried artefacts and debris, excavating the spoil mounds to remove any artefacts, undertaking visual and magnetic searches and delimiting the extent of the debris field. The fieldwork for 2003 included using an excavation ROV to remove the top layer of silt that had covered the wreck leaving the delicate excavation to be done by divers with airlifts. A Sonardyne Fusion Acoustic Positioning System (APS) was used on the 4 week project to provide high accuracy positioning for support vessel, ROV and divers. Archaeological and Historical Background The Mary Rose was one of the first ships built during the early years of the reign of King Henry VIII, probably in Portsmouth. She served as Flagship during Henry’s First French War and was substantially refitted and rebuilt during her 36 year long life. The Mary Rose sank in 1545 whilst defending Portsmouth from the largest invasion fleet ever known, estimated at between 30,000 and 50,000 individuals and between 150 and 200 vessels.