DRR Workshops Compiled Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village & Town Directory ,Darjiling , Part XIII-A, Series-23, West Bengal

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERmS 23 'WEST BENGAL DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XIll-A VILLAGE & TO"WN DIRECTORY DARJILING DISTRICT S.N. GHOSH o-f the Indian Administrative Service._ DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS WEST BENGAL · Price: (Inland) Rs. 15.00 Paise: (Foreign) £ 1.75 or 5 $ 40 Cents. PuBLISHED BY THB CONTROLLER. GOVERNMENT PRINTING, WEST BENGAL AND PRINTED BY MILl ART PRESS, 36. IMDAD ALI LANE, CALCUTTA-700 016 1988 CONTENTS Page Foreword V Preface vn Acknowledgement IX Important Statistics Xl Analytical Note 1-27 (i) Census ,Concepts: Rural and urban areas, Census House/Household, Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes, Literates, Main Workers, Marginal Workers, N on-Workers (ii) Brief history of the District Census Handbook (iii) Scope of Village Directory and Town Directory (iv) Brief history of the District (v) Physical Aspects (vi) Major Characteristics (vii) Place of Religious, Historical or Archaeological importance in the villages and place of Tourist interest (viii) Brief analysis of the Village and Town Directory data. SECTION I-VILLAGE DIRECTORY 1. Sukhiapokri Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 31 (b) Village Directory Statement 32 2. Pulbazar Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 37 (b) Village Directory Statement 38 3. Darjiling Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 43 (b) Village Directory Statement 44 4. Rangli Rangliot Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 49- (b) Village Directory Statement 50. 5. Jore Bungalow Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 57 (b), Village Directory Statement 58. 6. Kalimpong Poliee Station (a) Alphabetical list of viI1ages 62 (b)' Village Directory Statement 64 7. Garubatban Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 77 (b) Village Directory Statement 78 [ IV ] Page 8. -

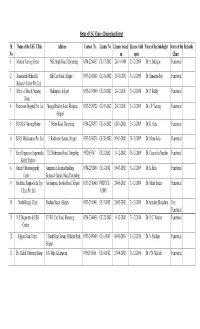

Status of USG Clinic of Darjeeling District Sl

Status of USG Clinic of Darjeeling District Sl. Name of the USG Clinic Address Contact No. License No. License issued License valid Name of the Sonologist Status of the Remarks No. on upto Clinic 1. Mariam Nursing Home N.B. Singh Road, Darjeeling 0354-2254637 CE-17-2002 24-11-1986 31-12-2009 Dr. S. Siddique Functional 2. Anandalok Medical & Hill Cart Road, Siliguri 0353-2510010 CE-18-2002 29-03-2001 31-12-2009 Dr. Shusanta Roy Functional Research Centre Pvt. Ltd. 3. Mitra`s Clinic & Nursing Hakimpara, Siliguri 0353-2431999 CE-23-2002 24-12-2001 31-12-2008 Dr. P. Reddy Functional Home 4. Paramount Hospital Pvt. Ltd. Mangal Panday Road, Khalpara, 0353-2530320 CE-19-2002 28-12-2001 31-12-2009 Dr. J.P. Tayung Functional Siliguri 5. D.D.M.A. Nursing Home 7, Nehru Road, Darjeeling 0354-2254337 CE-16-2002 02-01-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. K. Saha Functional 6. B.B.S. Mediscanner Pvt. Ltd 3, Rashbehari Sarani, Siliguri 0353-2434230 CE-20-2002 09-01-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. Mintu Saha Functional 7. Sono Diagnostic Sagarmatha 7/2/2 Robertson Road, Darjeeling 9832063347 CE-2-2002 13-12-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. Chayanika Nandan Functional Health Enclave 8. Omkar Ultrasonography Anjuman-E-Islamia Building, 0354-2252490 CE-3-2002 05-03-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. K Saha Functional Centre Botanical Garden Road, Darjeeling 9. Suraksha Diagnostic & Eye Ashrampara, Sevoke Road, Siliguri 0353-2530640 PNDT/CE- 28-05-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. Mukti Sarkar Functional Clinic Pvt. -

The Study Area

THE STUDY AREA 2.1 GENERALFEATURES 2.1.1 Location and besic informations ofthe area Darjeeling is a hilly district situated at the northernmost end of the Indian state of West Bengal. It has a hammer or an inverted wedge shaped appearance. Its location in the globe may be detected between latitudes of 26° 27'05" Nand 27° 13 ' 10" Nand longitudes of87° 59' 30" and 88° 53' E (Fig. 2. 1). The southern-most point is located near Bidhan Nagar village ofPhansidewa block the nmthernmost point at trijunction near Phalut; like wise the widest west-east dimension of the di strict lies between Sabarkum 2 near Sandakphu and Todey village along river Jaldhaka. It comprises an area of3, 149 km . Table 2.1. Some basic data for the district of Darjeeling (Source: Administrative Report ofDatjeeling District, 201 1- 12, http://darjeeling.gov.in) Area 3,149 kmL Area of H ill portion 2417.3 knr' T erai (Plains) Portion 731.7 km_L Sub Divisoins 4 [Datjeeling, Kurseong, Kalimpong, Si1iguri] Blocks 12 [Datjeeling-Pulbazar, Rangli-Rangliot, Jorebunglow-Sukiapokhari, Kalimpong - I, Kalimpong - II, Gorubathan, Kurseong, Mirik, Matigara, Naxalbari, Kharibari & Phansidewa] Police Stations 16 [Sadar, Jorebunglow, Pulbazar, Sukiapokhari, Lodhama, Rangli- Rangliot, Mirik, Kurseong, Kalimpong, Gorubathan, Siliguri, Matigara, Bagdogra, Naxalbari, Phansidewa & Kharibari] N o . ofVillages & Corporation - 01 (Siliguri) Towns Municipalities - 04 (Darjeeling, Kurseong, Kalimpong, Mirik) Gram Pancbayats - 134 Total Forest Cover 1,204 kmL (38.23 %) [Source: Sta te of Forest -

Eastern Himalayas

JANUARY 2013 Eastern Himalayas A quarterly newsletter of the ATREE Eastern Himalayas / Northeast India Programme VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3 © Urbashi© Pradhan/ATREE The old man and the bees “I would get irritated by the buzzing of bees visiting the orange orchard during flowering season. It was unbearable!” recalls Pratap baje (grandfather), sipping his tea on a cold winter morning. “So many bees…so many different kinds! This whole valley would smell so good with the aroma of orange flowers. It was as if someone had sprayed some perfume!” The old farmer in his 80s was my host in the village I asked him about bees in the wild and he recalled of Zoom, Sikkim. Memories seemed to flash across the days when he would go honey hunting with his wrinkled face as he spoke. “I had three hives friends in the dense forest patches nearby. “If you and they would be full of honey this season. One go now you will not even find a dead bee. A bottle was attacked by a malsapro (yellow-throated of honey costs five hundred rupees today. marten).” He then pointed to an ageing orange Everything is gone," he says in a resigned manner. tree. “In 1974 (confirms the year with his wife) this He thinks the use of pesticides killed both harmful very tree yielded 5218 fruits. We sat and counted and useful insects and that there is no food for bees each one of them. Now even a mature tree does in the wild because the forests have been cleared. not yield more than 1500. -

IJMRA-15482.Pdf

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 9 Issue 5, May 2019, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Spatial concentration of victims of crime against women in Darjeeling district Dr.Gopal Prasad Abstract In this research paper an attempt has been made to study the concentration of women victims of Darjeeling district extending across the hill and terai region of northern part of West Bengal. The study is further carried out with the Keywords: help of crime data collected from Superintendent of Victims; Police office, Darjeeling and Commissionerate of Police office, Siliguri. Analysis is done at regional, block, police Concentration; station and village/town level to identify the Regional; concentration of victims of crime. Maximum percentage Crime rate; of victims hailed in terai region than the hills.Further Location quotient method is used to know the Types of crime; villages/towns having high concentration of victims. The number of villages having high concentration of victims is based on the LQ value above 1. The terai belt of district is much developed than the hill in terms of transportation, urbanisation, etc. The other factors like socio-economic condition and demographic characteristics is analysed to see its impact on concentration of victims and for the purpose District Census Handbook of Darjeeling is consulted. -

Darjeeling.Pdf

0 CONTENT 1. INTRODUCTION............................................................................ Pg. 1-2 2. DISTRICT PROFILE ……………………………………………………………………….. Pg. 3- 4 3. HISTORY OF DISASTER ………………………………………………………………… Pg. 5 - 8 4. DO’S & DON’T’S ………………………………………………………………………….. Pg. 9 – 10 5. TYPES OF HAZARDS……………………………………………………………………… Pg. 11 6. DISTRICT LEVEL & LINE DEPTT. CONTACTS ………….……………………….. Pg. 12 -18 7. SUB-DIVISION, BLOCK LEVEL PROFILE & CONTACTS …………………….. Pg. 19 – 90 8. LIST OF SAR EQUIPMENTS.............................................................. Pg. 91 - 92 1 INTRODUCTION Nature offers every thing to man. It sustains his life. Man enjoys the beauties of nature and lives on them. But he also becomes a victim of the fury of nature. Natural calamities like famines and floods take a heavy toll of human life and property. Man seems to have little chance in fighting against natural forces. The topography of the district of Darjeeling is such that among the four sub-divisions, three sub-divisions are located in the hills where disasters like landslides, landslip, road blockade are often occurred during monsoon. On the other side, in the Siliguri Sub-Division which lies in the plain there is possibility of flood due to soil erosion/ embankment and flash flood. As district of Darjeeling falls under Seismic Zone IV the probability of earthquake cannot be denied. Flood/ cyclone/ landslide often trouble men. Heavy rains results in rivers and banks overflowing causing damage on a large scale. Unrelenting rains cause human loss. In a hilly region like Darjeeling district poor people do not have well constructed houses especially in rural areas. Because of incessant rains houses collapse and kill people. Rivers and streams overflow inundating large areas. Roads and footpaths are sub merged under water. -

Sjunn Siksumhiniii 2001-2002

Sjunn siKsuMHiniii ANNUAL PLAN (FOR UPE COMPONENT) 2001-2002 DARJEELING GORKHA HILL COUNCIL STATE : WEST BENGAL NIEPA DC D11374 3 7 2 . ilBRARY & DOrUMiWTfiT'JOW CWlim Nalfionil ■ 2.«r!tu'c c f h.i;scatiauii| Wannuj)? . ad .Aaai:ni^triitiea. j 1 7 -B. Sci ^uror.indo Mar|, | New Dfclhi-llGCJ.6 k i r *) *2/. »oc, No.............PlIlJaSLi ^ D«te——— — — -JtL/-r-,fiu^iMiiirii^ ^ ^ DA»J££UNG GQKKHA M .5/ '■%{- "• ■ ■ y 0ARJC6MNG % m / ti & «r w,. M m . ^ . i'^f-' -' 't*:Ti,“!- . ' V'V u •V, • •-#*•>■ ••'•' - ’ -t ; ! . ' ^'’r •• • ^'' ■ "* ' ? / / }'i.m y' y ' .if:' v-' :.'K> :-i^* INTRODUCTION Daijeeling Gorkha Hill Council was established under the provisions of Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council Act 1988 with the objective of total social, economic, cultural and educational upliftment of Gorkha and other communities of people living in the Hill areas of Daijeeling District under the jurisdiction of Daijeeling Gorkha Hill Council. The jurisdiction of the Hill Council covers an area of 2476 sq Km covering three Revenue subdivisions of Kalimpong, Kurseong and Daijeeling and 13 mouzas of Siliguri Revenue Subdivision. Hence, unlike a prototype district, Gorkha Hill Council is an autonomous body with 28 elected representatives as its Councillors from 28 Constituencies and 14 councillors are nominated. It has an Executive Cuncil consisting of 15 Executive Councillors of whom 13 are nominated amongst the elected councillors and the remaining two are nominated. The Chairman is also the Chief Executive Councillor of the Executive Council. Under the provisions of Daijeeling Gorkha Hill Council Act, the executive powers of the State Govt relating to the management, control and supervision of the important departments mainly covering developmental functions and activities have been transferred to the Hill Council. -

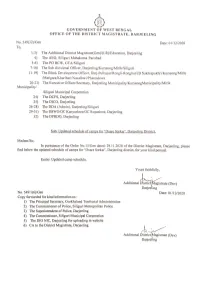

OFFICE of the COMMISSIONER of POLICE SPECIAL BRANCH Slliguri POLICE COMMISSIONERATE Memo No

Election Urgent GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF POLICE SPECIAL BRANCH SlLIGURI POLICE COMMISSIONERATE www.siliguripolice.org Memo no. 104/Election Cell, SPC Dated 28/02/2021. From The Commissioner of Police, Siliguri Police Commissionerate, Siliguri To The D.M. & DEO, Darjeeling, Sub Area Domination Schedule in Siliguri Police station, Pradhannagar Police Station, Matigara Police Station, Bagdogra Police Station, Dist. Darjeeling under Siliguri Police Commissionerate regarding In sending herewith the Area Domination Schedule of SSB 72 BN G. Company w.e.f. 01.03.2021 to 07/03/2021 in the area of Siliguri Police station, Pradhannagar Police Station, Matigara Police Station, Bagdogra Police Station under 25, 26, 27 AC, Dist. Darjeeling under Siliguri Police Commissionerate, Siliguri. This is for information please. Encl: As stated. Commissioner of Police, Siliguri Police Commissionerate, Siliguri Distict Darjeeling Darjeeling Darjeeling Darjeeling Darjeeling Darjeeling 1 3/3/2021 3/2/2021 3/1/2021 2 Date of Route March Siliguri Police station, Pradhannagar Police Station, Matigara Police Station, Bagdogra Police Station under 25, 26, 27 AC, Dist. Darjeeling under under Siliguri Police Commissionerate. Police under under Siliguri Darjeeling Dist. AC, 27 26, under 25, Station Bagdogra Police Station, Police Matigara Station, Pradhannagar Police station, Police Siliguri SLG SLG SLG SLG SLG SLG 3 Sub-Division Municipality Municipality Municipality Matigara Matigara Matigara Matigara Block Block Block 4 Block/Municipality PDN PS PDN PS Siliguri Siliguri MTG MTG 5 Police Station Morning shift Morning shift Morning shift Morning Evening shift Evening shift Evening shift 15.00 hrs to to 15.00 hrs to 15.00 hrs to 15.00 hrs 08.00 hrs to to hrs 08.00 to hrs 08.00 to hrs 08.00 20.00 20.00 hrs 20.00 hrs 20.00 hrs 13.00 hrs 13.00 hrs 13.00 hrs 13.00 Time 6 Dangipara, Dangipara, Sukna T.G, Sukna T.G, Cha Bagan Cha Bagan Siliguri Jn. -

2020120213.Pdf

ANNEXURE-A SCHEDULE OF CAMPS FOR DUARE SARKAR, DARJEELING DISTRICT Name of Sl block/muni Name of GP/Ward No. Location Dates No. cipality 01.12.2020, 15.12.2020, Pokhriabong I Selimbong T.E Pry School 04.01.2021, 18.01.2021 02.12.2020, 16.12.2020, Pokhriabong III Nagri Farm H.S School 05.01.2021, 19.01.2021 Yuwak Sangh Community 03.12.2020, 17.12.2020, Sukhia Simana Hall 06.01.2021, 20.01.2021 04.12.2020, 18.12.2020, Dhotrieah Gram Panchayat Office 07.01.2021, 21.01.2021 Yuwak Sangh Community 07.12.2020, 21.12.2020, Plungdung Hall 08.01.2021, 22.01.2021 08.12.2020, 22.12.2020, Lingia Marybong Gram Panchayat Office 09.01.2021, 25.01.2021 Pokhriabong Bazar 01.12.2020, 15.12.2020, Pokhriabong II Community Hall 04.01.2021, 18.01.2021 02.12.2020, 16.12.2020, Rangbhang 4thmile Community Hall Jorebungalow 05.01.2021, 19.01.2021 1 Sukhiapokhri 03.12.2020, 17.12.2020, Block Permaguri Mim T.E Pry School 06.01.2021, 20.01.2021 04.12.2020, 18.12.2020, Rangbull Gurashdara Community Hall 07.01.2021, 21.01.2021 Ghoom Bhanjyang 07.12.2020, 21.12.2020, Ghoom Community Hall 08.01.2021, 22.01.2021 08.12.2020, 22.12.2020, Upper Sonada Gram Panchayat Office 09.01.2021, 25.01.2021 09.12.2020, 23.12.2020, Lower Sonada I Scot Mission Jr Basic School 11.01.2021, 27.01.2021 10.12.2020, 24.12.2020, Mundakothi Gram Panchayat Office 12.01.2021, 28.01.2021 09.12.2020, 23.12.2020, Lower Sonada II Gram Panchayat Office 11.01.2021, 27.01.2021 Rasic Community Hall 10.12.2020, 24.12.2020, Gorabari Margarets Hope 12.01.2021, 28.01.2021 02.12.2020 15.12.2020 Badamtam Gram Panchayat Office 02.01.2021 18.01.2021 03.12.2020 16.12.2020 Bijanbari-Pulbazar Gram Panchayat Office 03.01.2021 19.01.2021 04.12.2020 17.12.2020 Chungtong Gram Panchayat Office Darjeeling 04.01.2021 2 Pul Bazar Dev. -

Darjeeling 2020-21

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN DARJEELING 2020-21 Government of West Bengal Office of District Magistrate, Darjeeling Department Of Disaster Management Tel/Fax No. : 0354-2255749 Email id.: [email protected] INDEX PAGE NOS. NOS. CONTENTS Emergency Control Numbers 1. CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION 1-4 1.1 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES 1 1.2 AUTHORITY FOR DDMP 1 1.3 EVOLUTION OF DDMP 2 1.4 STAKEHOLDERS AND THEIR RESPONSIBILITIES 3 1.5 HOW TO USE DDMP 3 1.6 APPROVAL MECHANISM OF DDMP 4 1.7 REVIEW AND UPDATEN OD D.D.M.P 4 2. CHAPTER II – DISTRICT HAZARD RISK VULNERABILITY AND CAPACITY ASSESSMENT 5-27 (HRVCA) 2.1 DISTRICT PROFILE (GEOGRAPHICAL, ADMINISTRATIVE AND DEMOGRAPHIC) 5 a District Landuse/Landcover Map 7 b District Geological Map 8 c District Administrative Map 9 d District Mp of Transpot Lines 10 e District Map of Settlements 11 2.2 HAZARD PROFILE 12 2.3 (i) AREAS AFFECTED BY CALAMITY (2019) 13-15 Monsoon Calamity Assessment Report (2019) 16 2.3 (ii) AREAS AFFECTED BY CALAMITY (2018) 17-21 2.4 INVENTORY OF PAST DISASTERS 20-23 2.5 HVRCA ACROSS THE FOUR SUBDIVISIONS 26-27 3. CHAPTER III - INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR DISASTER MANAGEMENT 28-32 3.1 ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE OF DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY 28 3.2 FUNCTIONAL FLOW AND HIERARCHICAL STRUCTURE OF AUTHORITIES AND COMMITTEES 29 3.3 POWERS AND FUNCTIONS OF DDMA 29-31 3.4 STRENGTHENING DDMA 32 4. CHAPTER IV - PREVENTIVE MITIGATION MEASURES 33-34 4.1 PREVENTIVE MEASURES ADOPTED AT EACH BLOCK 33 4.2 DISTRICT LEVEL MITIGATION PROJECTS UNDER NATIONAL LEVEL 34 4.3 PREVENTIVE GUIDELINES OF N.D.M.A FOR HEALTH EMERGENCIES – COVID-19 PANDEMIC 34 5. -

Full Article

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CONSERVATION SCIENCE ISSN: 2067-533X Volume 7, Issue 3, July-September 2016: 735-752 www.ijcs.uaic.ro TRADITIONAL USES AND CONSERVATIVE LIFESTYLE OF LEPCHA TRIBE THROUGH SUSTAINABLE BIORESOURCE UTILIZATION – CASE STUDIES FROM DARJEELING AND NORTH SIKKIM, INDIA Debnath PALIT¹*, Arnab BANERJEE² ¹Assistant Professor in Botany, Durgapur Government College, J.N.Avenue, Durgapur-713214, West Bengal, India 2UTD, Dept. of Environmental Science, Sarguja University, Chattisgarh, India CG-497001 Abstract The major objective of the present communication was to document the traditional knowledge regarding ethnomedicinal uses of different plant species and conservative lifestyle of the Lepcha community in Darjeeling and some parts of North Sikkim. Extensive field surveys were undertaken between 2006 (groundwork) and 2010 (comprehensive) in selected study sites of North Sikkim and Darjeeling district of West Bengal, India. Information was gathered using semi-structured formats, interviews, and group discussions. Lepchas have profound knowledge about the plants and animals in their surroundings and are reputed for their age- long traditions in herbal medicine. The present work brings into light 34 plant species from the ethno botanical survey among Lepcha people in Darjeeling district, West Bengal, India, which have multifarious uses. The major areas of their utilization include folk medicine. Present ethnobotanical survey among the Lepchas in North Sikkim, India brings into light 44 plant species that indigenous people use in medicinal purposes and the plants they use to make different domestic utensils and musical instruments. Based on our field investigations, it appears that habitat loss due to increasing anthropogenic activities has promoter greater damage towards bioresources diversity of the concerned study sites. -

Monika Lakandri.Pdf

Women Empowerment and Political Participation: A Study of Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council and Gorkhaland Territorial Administration A Dissertation Submitted To Sikkim University In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Philosophy By Monica Lakandri Department of Political Science School of Social Sciences February, 2018 DECLARATION Date:______________ I, Monica Lakandri, do hereby declare that the subject matter of this dissertation is the record of work done by me, that the contents of this dissertation did not form basis of the award of any previous degree to me or to the best of my knowledge to anybody else, and the dissertation has not been submitted by me for any research degree in any other university/institute. This is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master in Philosophy in the Department of Political Science, School of Social Sciences, Sikkim University. Name: Monica Lakandri Registration Number: 16/M.Phil/PSC/07 We recommend that this dissertation be placed before the examiner for evaluation. Prof. Mohammad Yasin Dr. Gadde Omprasad Head of Department Supervisor CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation entitled “Women Empowerment and Political Participation: A Study of Darjeeling Gorkha Hil Council and Gorkhaland Territorial Administration” submitted to Sikkim University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Political Science is the result of bonafide research work carried out by Ms Monica Lakandri under my guidance and supervision. No part of the dissertation has been submitted for any other degree, diploma, associateship and fellowship. All the assistance and help received during the course of the investigation have been duly acknowledged by her.