Hitler Comedy / Hitlerhoff by Thomas James Doig # 120773

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler As the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction," Studies in 20Th & 21St Century Literature: Vol

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 43 Issue 2 Article 44 October 2019 Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth- First Century French Fiction Marion Duval The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Duval, Marion (2019) "Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 43: Iss. 2, Article 44. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.2076 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction Abstract Adolf Hitler has remained a prominent figure in popular culture, often portrayed as either the personification of evil or as an object of comedic ridicule. Although Hitler has never belonged solely to history books, testimonials, or documentaries, he has recently received a great deal of attention in French literary fiction. This article reviews three recent French novels by established authors: La part de l’autre (The Alternate Hypothesis) by Emmanuel Schmitt, Lui (Him) by Patrick Besson and La jeunesse mélancolique et très désabusée d’Adolf Hitler (Adolf Hitler’s Depressed and Very Disillusioned Youth) by Michel Folco; all of which belong to the Twenty-First Century French literary trend of focusing on Second World War perpetrators instead of their victims. -

The Mind of Adolf Hitler: a Study in the Unconscious Appeal of Contempt

[Expositions 5.2 (2011) 111-125] Expositions (online) ISSN: 1747-5376 The Mind of Adolf Hitler: A Study in the Unconscious Appeal of Contempt EDWARD GREEN Manhattan School of Music How did the mind of Adolf Hitler come to be so evil? This is a question which has been asked for decades – a question which millions of people have thought had no clear answer. This has been the case equally with persons who dedicated their lives to scholarship in the field. For example, Alan Bullock, author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, and perhaps the most famous of the biographers of the Nazi leader, is cited in Ron Rosenbaum’s 1998 book, Explaining Hitler, as saying: “The more I learn about Hitler, the harder I find it to explain” (in Rosenbaum 1998, vii). In the same text, philosopher Emil Fackenheim agrees: “The closer one gets to explicability the more one realizes nothing can make Hitler explicable” (in Rosenbaum 1998, vii).1 Even an author as keenly perceptive and ethically bold as the Swiss philosopher Max Picard confesses in his 1947 book, Hitler in Ourselves, that ultimately he is faced with a mystery.2 The very premise of his book is that somehow the mind of Hitler must be like that of ourselves. But just where the kinship lies, precisely how Hitler’s unparalleled evil and the everyday workings of our own minds explain each other – in terms of a central principle – the author does not make clear. Our Deepest Debate I say carefully, as a dispassionate scholar but also as a person of Jewish heritage who certainly would not be alive today had Hitler succeeded in his plan for world conquest, that the answer Bullock, Fackenheim, and Picard were searching for can be found in the work of the great American philosopher Eli Siegel.3 First famed as a poet, Siegel is best known now for his pioneering work in the field of the philosophy of mind.4 He was the founder of Aesthetic Realism.5 In keeping with its name, this philosophy begins with a consideration of strict ontology. -

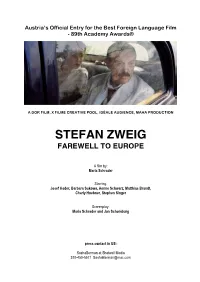

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

Revealing and Concealing Hitler's Visual Discourse: Considering "Forbidden" Images with Rhetorics of Display

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English Summer 8-20-2012 Revealing and Concealing Hitler's Visual Discourse: Considering "Forbidden" Images with Rhetorics of Display Matthew G. Donald College of Arts and Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Recommended Citation Donald, Matthew G., "Revealing and Concealing Hitler's Visual Discourse: Considering "Forbidden" Images with Rhetorics of Display." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/134 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVEALING AND CONCEALING HITLER‟S VISUAL DISCOURSE: CONSIDERING “FORBIDDEN” IMAGES WITH RHETORICS OF DISPLAY by MATTHEW DONALD Under the Direction of Mary Hocks ABSTRACT Typically, when considering Adolf Hitler, we see him in one of two ways: A parodied figure or a monolithic figure of power. I argue that instead of only viewing images of Hitler he wanted us to see, we should expand our view and overall consideration of images he did not want his audiences to bear witness. By examining a collection of photographs that Hitler censored from his audiences, I question what remains hidden about Hitler‟s image when we are constantly shown widely circulated images of Hitler. To satisfy this inquiry, I utilize rhetorics of display to argue that when we analyze and include these hidden images into the Hitlerian visual discourse, we further complicate and disrupt the Hitler Myth. -

German Videos - (Last Update December 5, 2019) Use the Find Function to Search This List

German Videos - (last update December 5, 2019) Use the Find function to search this list Aguirre, The Wrath of God Director: Werner Herzog with Klaus Kinski. 1972, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A band of Spanish conquistadors travels into the Amazon jungle searching for the legendary city of El Dorado, but their leader’s obsessions soon turn to madness.LLC Library CALL NO. GR 009 Aimée and Jaguar DVD CALL NO. GR 132 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder. with Brigitte Mira, El Edi Ben Salem. 1974, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A widowed German cleaning lady in her 60s, over the objections of her friends and family, marries an Arab mechanic half her age in this engrossing drama. LLC Library CALL NO. GR 077 All Quiet on the Western Front DVD CALL NO. GR 134 A/B Alles Gute (chapters 1 – 4) CALL NO. GR 034-1 Alles Gute (chapters 13 – 16) CALL NO. GR 034-4 Alles Gute (chapters 17 – 20) CALL NO. GR 034-5 Alles Gute (chapters 21 – 24) CALL NO. GR 034-6 Alles Gute (chapters 25 – 26) CALL NO. GR 034-7 Alles Gute (chapters 9 – 12) CALL NO. GR 034-3 Alpen – see Berlin see Berlin Deutsche Welle – Schauplatz Deutschland, 10-08-91. [ Opening missing ], German with English subtitles. LLC Library Alpine Austria – The Power of Tradition LLC Library CALL NO. GR 044 Amerikaner, Ein – see Was heißt heir Deutsch? LLC Library Annette von Droste-Hülshoff CALL NO. GR 120 Art of the Middle Ages 1992 Studio Quart, about 30 minutes. -

Of Adolf Hitler's Antisemitism in Vienna

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2021 An Education in Hate: The “Granite Foundation” of Adolf Hitler’s Antisemitism in Vienna Madeleine M. Neiman Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the European History Commons, Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Neiman, Madeleine M., "An Education in Hate: The “Granite Foundation” of Adolf Hitler’s Antisemitism in Vienna" (2021). Student Publications. 932. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/932 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Education in Hate: The “Granite Foundation” of Adolf Hitler’s Antisemitism in Vienna Abstract Adolf Hitler’s formative years in Vienna, from roughly 1907 to 1913, fundamentally shaped his antisemitism and provided the foundation of a worldview that later caused immense tragedy for European Jews. Combined with a study of Viennese culture and society, the first-hand accounts of Adolf Hitler and his former friends, August Kubizek and Reinhold Hanisch, reveal how Hitler’s vicious antisemitic convictions developed through his devotion to Richard Wagner and his rejection of Viennese “Jewish” Modernism; his admiration of political role models, Georg Ritter von Schönerer and Dr. Karl Lueger; his adoption of the rhetoric and dogma disseminated by antisemitic newspapers and pamphlets; and his perception of the “otherness” of Ostjuden on the streets of Vienna. Altogether, Hitler’s interest in and pursuit of these major influences on his extreme and deadly prejudice against Jews have illuminated how such a figure became a historical possibility. -

German Captured Documents Collection

German Captured Documents Collection A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by Allan Teichroew, Fred Bauman, Karen Stuart, and other Manuscript Division Staff with the assistance of David Morris and Alex Sorenson Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2011 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms011148 Latest revision: 2012 October Collection Summary Title: German Captured Documents Collection Span Dates: 1766-1945 ID No.: MSS22160 Extent: 249,600 items ; 51 containers plus 3 oversize ; 20.5 linear feet ; 508 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in German with some English and French Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: German documents captured by American military forces after World War II consisting largely of Nazi Party materials, German government and military records, files of several German officials, and some quasi-governmental records. Much of the material is microfilm of originals returned to Germany. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Wiedemann, Fritz, b. 1891. Fritz Wiedemann papers. Organizations Akademie für Deutsches Recht (Germany) Allgemeiner Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund. Deutsches Ausland-Institut. Eher-Verlag. Archiv. Germany. Auswärtiges Amt. Germany. Reichskanzlei. Germany. Reichsministerium für die Besetzten Ostgebiete. Germany. Reichsministerium für Rüstung und Kriegsproduktion. Germany. Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda. -

“The Bethlehem of the German Reich”

“THE BETHLEHEM OF THE GERMAN REICH” REMEMBERING, INVENTING, SELLING AND FORGETTING ADOLF HITLER’S BIRTH PLACE IN UPPER AUSTRIA, 1933-1955 By Constanze Jeitler Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Andrea Pető Second Reader: Professor Constanin Iordachi CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 CEU eTD Collection STATEMENT OF COPYRIGHT “Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author.” CEU eTD Collection i CEU eTD Collection ii ABSTRACT This thesis is an investigation into the history of the house where Adolf Hitler was born in the Upper Austrian village Braunau am Inn. It examines the developments in the period between 1933 and 1955. During this time high-ranking Nazis, local residents, tourists and pilgrims appropriated the house for their purposes by creating various narratives about this space. As unimportant as the house might have been to Hitler himself from the point of view of sentimentality and childhood nostalgia, it had great propaganda value for promoting the image of the private Führer. Braunau itself was turned into a tourist destination and pilgrimage site during the Nazi period—and beyond. -

Rise of the Nazis Adolf Hitler Was Born an Austrian Citizen and Roman

Rise of the Nazis Adolf Hitler was born an Austrian citizen and Roman Catholic at 6:30 PM on April 20 1889 at an inn called the Gasthof Zum Pommer in the town of Braunau-am-inn. Adolf's father- Alois Hitler- constantly reinforced correct behaviour with, sometimes very violent, punishment. After Adolf's elder brother- Alois- fled from home at the age of 14, Adolf became his father's chief target of rage. At the same time, Adolf's mother- Klara Pölzl- showered her son with love and affection, as any mother would. When Adolf was three years of age, the Hitler family moved to Passau, along the Inn River on the German side of the border. The family moved once again in 1895 to the farming community of Hafield. Following another family move, Adolf lived for six months across from a large Benedictine monastery. As a youngster, the young boy's dream was to enter the priesthood. However, by 1900, his artistic talents surfaced. Adolf was educated at the local village and monastery schools and, at age 11, Hitler was doing well enough to be eligible for either the university preparatory "gymnasium" or the technical/scientific Realschule (secondary school). Alois Hitler enrolled his son in the latter, hoping that he might become a civil servant. This was not to be. Adolf would later claim that he wanted to be an artist and he deliberately failed his examinations to spite his father. In 1903, Alois Hitler died from a pleural hemorrhage, leaving his family with enough money to live comfortably without needing to work. -

Alexis Wilicki1 I

A MATRIARCH TO HIS PATRIARCHY: HITLER’S SEARCH FOR NAZI GERMANY’S MOTHER Alexis Wilicki1 I. INTRODUCTION At the hands of Führer Adolf Hitler, Nazi Germany appeared to mold into a nation heavily littered in patriarchy, housing legislation and propaganda that enforced and promoted stereotypical gender roles.2 Aryan women were meant to be mothers and homemakers, raising their children to be promoters and supporters of the Führer’s ideal nation, while Aryan men were meant to provide for their families and the nation by way of dedicating themselves to the workforce.3 With each role acting as a calculated instrument in Adolf Hitler’s pursuit toward his ideal nation, Hitler assured compliance of these pre-determined roles through legislation, which promoted the relocation of women from the workforce to the home amongst other things.4 However, although these enactments appeared to move toward the development of a patriarchy, a closer look at the legislation enacted at the hands of the Führer and Hitler’s personal adolescence reveal that it was not a patriarchy he sought, but a matriarch to oversee his infantile nation.5 This Article will first explore the pre-established roles of Aryan men and women in Nazi Germany, and the laws that were enacted to ensure these roles, specifically those concentrated on women. This Article will then explore the adolescence and early adulthood of Adolf Hitler as it pertains to his relationships with his mother and father, and the experiences that stemmed from those relationships. Upon this exploration, a connection will be made between Hitler’s relationship with his mother, and his concentration on Aryan 1 Associate Nuremberg Editor, Rutgers Journal of Law and Religion; J.D. -

THE KANGAROO CHRONICLES by Dani Levy 8 CONTENT OFFICIAL SELECTION - VENICE ORIZZONTI

BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ by Burhan Qurbani MY LITTLE SISTER by Stéphanie Chuat & Véronique Reymond NARCISSUS AND GOLDMUND by Stefan Ruzowitzky MY NEIGHBOR ADOLF by Leon Prudovsky HINTERLAND by Stefan HELLO AGAIN - A WEDDING A DAY by Maggie Peren DIABOLIK by Manetti Bros. THE BIKE THIEF by Matt Chambers BETA CINEMA VENICE / TORONTO 2020 NOWHERE SPECIAL by Uberto Pasolini KARNAWAL by Juan Pablo Félix KINDRED by Joe Marcantonio THE AUSCHWITZ REPORT by Peter Bebjak THE KANGAROO CHRONICLES by Dani Levy 8 CONTENT OFFICIAL SELECTION - VENICE ORIZZONTI NOWHERE SPECIAL by Uberto Pasolini ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. Page 04 OFFICIAL SELECTION - TIFF INDUSTRY SELECTS KARNAWAL by Juan Pablo Félix ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Page 08 CURRENT LINE-UP KINDRED by Joe Marcantonio ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. Page 12 THE AUSCHWITZ REPORT by Peter Bebjak ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Göring, Goebbels, Himmler, Heydrich and Revolutionary Totalitarian Oligarchy in the Third Reich

History in the Making Volume 10 Article 8 January 2017 Dark Apostles – Hitler’s Oligarchs: Göring, Goebbels, Himmler, Heydrich and Revolutionary Totalitarian Oligarchy in the Third Reich Athahn Steinback CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Steinback, Athahn (2017) "Dark Apostles – Hitler’s Oligarchs: Göring, Goebbels, Himmler, Heydrich and Revolutionary Totalitarian Oligarchy in the Third Reich," History in the Making: Vol. 10 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol10/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Athahn Steinback Dark Apostles – Hitler’s Oligarchs: Göring, Goebbels, Himmler, Heydrich and Revolutionary Totalitarian Oligarchy in the Third Reich By Athahn Steinback Abstract: In popular memory, the Third Reich and the Nazi party are all too often misremembered as a homogenous entity, entirely shaped and led by the figure of Adolf Hitler. This paper challenges the widely held misconception of a homogenous Nazi ideology and critically re-examines the governance of Nazi Germany by arguing that the Third Reich was not a generic totalitarian dictatorship, but rather, a revolutionary totalitarian oligarchy. The unique roles and revolutionary agendas of Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler, and Reinhard Heydrich, provide case studies to demonstrate the nature of this revolutionary totalitarian oligarchy. The role of Hitler as the chief oligarch of Nazi Germany remains critical to the entire system of governance.