Paper for Adapting Historical Narratives Gertjan Willems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antwerp in 2 Days | the Rubens House

Antwerp in 2 days | The Rubens House Rubens was a man of many talents. Besides being the gifted painter we all know, he was also a diplomat, a devoted family man, an art collector and an architect. Where better to begin this immersion in Rubens’s city than the house in which he lived and worked? Rubens as an architect Rubens was talented in many areas of life. Besides being the gifted painter we all know, he was also a diplomat, a devoted family man, an art collector and architect. Where better to begin this immersion in Rubens’s city than the house in which he lived and worked? When Rubens returned from Italy in 1608, at the age of 31, he came back with a case full of sketches and a head full of ideas. He purchased a plot of land with a house near his grandfather’s home (Meir 54) and converted it into his own Palazzetto. Take an hour to visit the Rubens House and to breathe in the atmosphere in the master’s house before setting off to explore his city. Rubens’s palazzetto on the Wapper was not yet complete when the artist was commissioned to work on the Baroque Jesuit church some distance away, at Hendrik Conscienceplein. On your way to Hendrik Conscienceplein, we would suggest you make a brief stop at another church: St James’s Church (St Jacobskerk) in Lange Nieuwstraat. This robust building dooms up rather unexpectedly among the houses, but its interior presents a perfect harmony between Gothic and Baroque: the elegant Middle Ages and the flamboyant style of the 17th century go hand-in-hand here. -

1 Unmasking the Fake Belgians. Other Representation of Flemish And

Unmasking the Fake Belgians. Other Representation of Flemish and Walloon Elites between 1840 and 1860 Dave Sinardet & Vincent Scheltiens University of Antwerp / Free University of Brussels Paper prepared for 'Belgium: The State of the Federation' Louvain-La-Neuve, 17/10/2013 First draft All comments more than welcome! 1 Abstract In the Belgian political debate, regional and national identities are often presented as opposites, particularly by sub-state nationalist actors. Especially Flemish nationalists consider the Belgian state as artificial and obsolete and clearly support Flemish nation-building as a project directed against a Belgian federalist project. Walloon or francophone nationalism has not been very strong in recent years, but in the past Walloon regionalism has also directed itself against the Belgian state, amongst other things accused of aggravating Walloon economic decline. Despite this deep-seated antagonism between Belgian and Flemish/Walloon nation-building projects its roots are much shorter than most observers believe. Belgium’s artificial character – the grand narrative and underpinning legitimation of both substate nationalisms - has been vehemently contested in the past, not only by the French-speaking elites but especially by the Flemish movement in the period that it started up the construction of its national identity. Basing ourselves methodologically on the assumption that the construction of collective and national identities is as much a result of positive self-representation (identification) as of negative other- representation (alterification), moreover two ideas that are conceptually indissolubly related, we compare in this interdisciplinary contribution the mutual other representations of the Flemish and Walloon movements in mid-nineteenth century Belgium, when the Flemish-Walloon antagonism appeared on the surface. -

A German William of Orange for Occupied Flanders: Frans Haepers, Groot-Nederland, and the Invention of Tradition1

A German William of Orange for Occupied Flanders: Frans Haepers, Groot-Nederland, and the Invention of Tradition1 Simon Richter (University of Pennsylvania) Abstract: During the Nazi occupation of Belgium, an effort was launched by Frans Haepers and the editorial staff of the weekly journal Volk en Kultuur to invent a Flemish tradition around the Dutch cultural icon William of Orange. The effort was based on two German-language historical novels, Wilhelm Kotzde-Kottenrodt’s Wilhelmus and Rudolf Kremser’s Der stille Sieger, which were subsequently translated into Dutch. The article argues that the Flemish recourse to William of Orange as mediated through the novels and their translation was a way to negotiate the conflicting collaborationist politics of Groot-Nederland, favored by Flemish nationalists, and the Großgermanisches Reich, favored by Flemish Nazis. Keywords: Willem van Oranje / William of Orange – Groot Nederland / Greater Netherlands – Vlaanderen en het ‘Derde Rijk’ / Flanders and the ‘Third Reich’ – Frans Haepers – Wilhelm Kotzde-Kottenrodt – Rudolf Kremser 1 The author is grateful to Prof. Dr. Uwe Puschner and his colleagues at the Friedrich Meinecke Institute of the Free University of Berlin and to the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for making possible a research stay in Berlin. Journal of Dutch Literature, 9.2 (2018), 76-91 Simon Richter 77 The 11 July 1942 issue of Volk en Kultuur: Weekblad voor Volksche Kunst en Wetenschap [Folk and Culture: Weekly for Völkisch Art and Science], a rightwing, semi-collaborationist Flemish nationalist journal, identified itself as the ‘Willem van Oranjenummer’ [William of Orange issue] and featured a full-size portrait of the ‘father of the fatherland’ on the cover. -

De Gedaantewisselingen Van De De Keyserlei

Aangeboden door Info Antwerp™© De gedaantewisselingen van de Keyserlei Historiek van de Keyserlei Een laan krijgt gestalte Vanhees Benoit Inleiding: Een laan zonder bomen Ondanks protestacties van milieuactivisten en nogal wat persaandacht, werden in november 2011 de 96 lindebomen in de Antwerpse Keyserlei gerooid. De majestueuze bomen waren een dertigtal jaren eerder aangepland. Op bevel van het stadsbestuur moesten ze wijken in het kader van de heraanleg en de dringende herwaardering van de eens zo bruisende stadsader. Zoals altijd in zo’n emotioneel geladen debatten kwamen voor- en tegenstanders aandragen met zowel zinvolle als met wat vergezochte argumenten. Lokale politici en hun raadgevers hadden daarbij uiteraard al meer dan louter één oog op de komende gemeenteraadsverkiezingen. Sommigen wierpen zich met hartstocht op als een soort patroonheiligen voor de fel geplaagde horecasector. Hun tegenstanders spelen dan weer in op de zucht van de burger naar wat groen en propere longen. Het mocht niet baten: terwijl het stadsbestuur nog maar eens een Spaanse architect een deel van Antwerpen ingrijpend liet hertekenen, speelde de Metropool haar eigenste Ramblas kwijt. De Keyserlei is voorlopig dus een laan zonder bomen. Dit is trouwens niet de eerste maal. Wie oude postkaarten op chronologische volgorde zou leggen (bv. aan de hand van datumstempels op postzegels, of aan de hand van de modellen auto’s in het straatverkeer) zou kunnen zien dat zo’n algemene kapping reeds eerder plaatsvond. Het einde van een tijdperk en een lei zonder bomen... We laten hier in het midden, wie het tot op welke hoogte bij het rechte eind moge hebben. Wat wel zo is, is dat de radicale ingreep als voorbereiding op de heraanleg van de Keyserlei een onbedoeld interessant neveneffect had. -

Reconstructions of the Past in Belgium and Flanders

Louis Vos 7. Reconstructions of the Past in Belgium and Flanders In the eyes of some observers, the forces of nationalism are causing such far- reaching social and political change in Belgium that they threaten the cohesion of the nation-state, and may perhaps lead to secession. Since Belgian independ- ence in 1831 there have been such radical shifts in national identity – in fact here we could speak rather of overlapping and/or competing identities – that the political authorities have responded by changing the political structures of the Belgian state along federalist lines. The federal government, the Dutch-speaking Flemish community in the north of Belgium and the French-speaking commu- nity – both in the southern Walloon region and in the metropolitan area of Brus- sels – all have their own governments and institutions.1 The various actors in this federal framework each have their own conceptions of how to take the state-building process further, underpinned by specific views on Belgian national identity and on the identities of the different regions and communities. In this chapter, the shifts in the national self-image that have taken place in Belgium during its history and the present configurations of national identities and sub-state nationalism will be described. Central to this chapter is the question whether historians have contributed to the legitimization of this evolving consciousness, and if so, how. It will be demonstrated that the way in which the practice of historiography reflects the process of nation- and state- building has undergone profound changes since the beginnings of a national his- toriography. -

Discord & Consensus

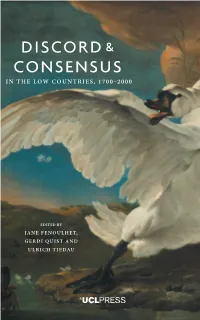

c Discor Global Dutch: Studies in Low Countries Culture and History onsensus Series Editor: ulrich tiedau DiscorD & Discord and Consensus in the Low Countries, 1700–2000 explores the themes D & of discord and consensus in the Low Countries in the last three centuries. consensus All countries, regions and institutions are ultimately built on a degree of consensus, on a collective commitment to a concept, belief or value system, 1700–2000 TH IN IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1700–2000 which is continuously rephrased and reinvented through a narrative of cohesion, and challenged by expressions of discontent and discord. The E history of the Low Countries is characterised by both a striving for consensus L and eruptions of discord, both internally and from external challenges. This OW volume studies the dynamics of this tension through various genres. Based C th on selected papers from the 10 Biennial Conference of the Association OUNTRI for Low Countries Studies at UCL, this interdisciplinary work traces the themes of discord and consensus along broad cultural, linguistic, political and historical lines. This is an expansive collection written by experts from E a range of disciplines including early-modern and contemporary history, art S, history, film, literature and translation from the Low Countries. U G EDIT E JANE FENOULHET LRICH is Professor of Dutch Studies at UCL. Her research RDI QUIST AND QUIST RDI E interests include women’s writing, literary history and disciplinary history. BY D JAN T I GERDI QUIST E is Lecturer in Dutch and Head of Department at UCL’s E DAU F Department of Dutch. -

A Short History of Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg

A Short History of Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg Foreword ............................................................................2 Chapter 1. The Low Countries until A.D.200 : Celts, Batavians, Frisians, Romans, Franks. ........................................3 Chapter 2. The Empire of the Franks. ........................................5 Chapter 3. The Feudal Period (10th to 14th Centuries): The Flanders Cloth Industry. .......................................................7 Chapter 4. The Burgundian Period (1384-1477): Belgium’s “Golden Age”......................................................................9 Chapter 5. The Habsburgs: The Empire of Charles V: The Reformation: Calvinism..........................................10 Chapter 6. The Rise of the Dutch Republic................................12 Chapter 7. Holland’s “Golden Age” ..........................................15 Chapter 8. A Period of Wars: 1650 to 1713. .............................17 Chapter 9. The 18th Century. ..................................................20 Chapter 10. The Napoleonic Interlude: The Union of Holland and Belgium. ..............................................................22 Chapter 11. Belgium Becomes Independent ...............................24 Chapter 13. Foreign Affairs 1839-19 .........................................29 Chapter 14. Between the Two World Wars. ................................31 Chapter 15. The Second World War...........................................33 Chapter 16. Since the Second World War: European Co-operation: -

Geschiedenis Mijner Jeugd Hendrik Conscience

Geschiedenis mijner jeugd Hendrik Conscience bron Hendrik Conscience, Geschiedenis mijner jeugd. A.W. Sijthof, Leiden z.j. [ca. 1880] Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/cons001gesc02_01/colofon.htm © 2007 dbnl 5 Geschiedenis mijner jeugd Voorhangsel Sedert zeventien jaren reeds had België het lot van vele kleine landen ondergaan: het was bij het reuzenlichaam van het zegevierende Frankrijk ingelijfd geworden. Napoleon-Buonaparte, alsdan in de volheid zijner macht, had de stad Antwerpen uitgekozen om in haren schoot de zeekrachten te verzamelen, die zijne gevreesde Arenden naar Engeland zouden overvoeren, om in Londen zelf den laatsten vijand zijner grootheid te gaan verpletten. De voormalige abdij van Sint-Michiel, bij den boord der Schelde, was tot stapel van het Fransche Zeewezen ingericht. Daar, op eene uitgestrekte timmerwerf, verhieven zich als door tooverij de ontzettende rompen van machtige linie-schepen en fregatten; en even was een dezer gevaarten van stapel geloopen, of men stelde eene nieuwe kiel op de nog onverkoelde slede. Het was op deze timmerwerf, - door de Franschen Chantier de la marine genaamd, - eene bedrijvigheid en een gerucht, waarvan men zich moeilijk een denkbeeld vormen zou. De slagen van duizende bijlen en hamers weergalmden er onverpoosd door de lucht; hier zuchtten de blaasbalgen der smidsen, daar krijschten de zagen door het hout, verder klonk het lied der matrozen, die op eenstemmige maat hunne krachten Hendrik Conscience , Geschiedenis mijner jeugd 6 inspanden, om de zwaarste lasten in de hoogte te hijschen. Eene wolk menschen zwermden er door elkander; maar ieder had zijn werk en wist zijne taak, en op aller aangezicht gloeide het vuur der haast. -

Antwerp in 3 Days | the Rubens House

Antwerp in 3 days | The Rubens House Rubens was a man of many talents. Besides being the gifted painter we all know, he was also a diplomat, a devoted family man, an art collector and an architect. Where better to begin this immersion in Rubens’s city than the house in which he lived and worked? Rubens as an architect When Rubens returned from Italy in 1608, at the age of 31, he came back with a case full of sketches and a head full of ideas. He purchased a plot of land with a house near his grandfather’s home (Meir 54) and converted it into his own Palazzetto. Take an hour to visit the Rubens House and to breathe in the atmosphere in the master’s house before setting off to explore his city. Rubens’s palazzetto on the Wapper was not yet complete when the artist was commissioned to work on the Baroque Jesuit church some distance away, at Hendrik Conscienceplein. The St Carolus Borromeus Church at Hendrik Conscienceplein is the epitome of Italian grandeur. With his knowledge of Italian architecture, Rubens undoubtedly contributed ideas for the façade, but his greatest achievements here are to be seen in the interior. Rubens designed the richly decorated chapel and its impressive marble high altar. Sadly, all that remains of the master’s 39 ceiling paintings are the sketches that are preserved in the church. The paintings themselves perished in a huge fire in 1718. The high altar merits particular attention: behind the enormous painting – it measures 4.0 x 5.35 metres – other works are concealed. -

Dutch. a Linguistic History of Holland and Belgium

Dutch. A linguistic history of Holland and Belgium Bruce Donaldson bron Bruce Donaldson, Dutch. A linguistic history of Holland and Belgium. Uitgeverij Martinus Nijhoff, Leiden 1983 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/dona001dutc02_01/colofon.php © 2013 dbnl / Bruce Donaldson II To my mother Bruce Donaldson, Dutch. A linguistic history of Holland and Belgium VII Preface There has long been a need for a book in English about the Dutch language that presents important, interesting information in a form accessible even to those who know no Dutch and have no immediate intention of learning it. The need for such a book became all the more obvious to me, when, once employed in a position that entailed the dissemination of Dutch language and culture in an Anglo-Saxon society, I was continually amazed by the ignorance that prevails with regard to the Dutch language, even among colleagues involved in the teaching of other European languages. How often does one hear that Dutch is a dialect of German, or that Flemish and Dutch are closely related (but presumably separate) languages? To my knowledge there has never been a book in English that sets out to clarify such matters and to present other relevant issues to the general and studying public.1. Holland's contributions to European and world history, to art, to shipbuilding, hydraulic engineering, bulb growing and cheese manufacture for example, are all aspects of Dutch culture which have attracted the interest of other nations, and consequently there are numerous books in English and other languages on these subjects. But the language of the people that achieved so much in all those fields has been almost completely neglected by other nations, and to a degree even by the Dutch themselves who have long been admired for their polyglot talents but whose lack of interest in their own language seems never to have disturbed them. -

International Review of the Red Cross, March 1975, Fifteenth Year

APR 2 5 1975 MARCH 1975 FIFTEENTH YEAR - No. 168 international review• of the red cross PROPERTY OF U. S, ARMY THe Jei:>GE A:'VOCATE GENERAL'S SCHOO\, INTER+ ARM'" CARITASUBRARY GENEVA INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE REO CROSS FOUNDED IN 1863 INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS Mr. ERIC MARTIN, Doctor of Medicine, Honorary Professor of the University of Geneva President (member since 1973) Mr. JEAN PICTET, Doctor of Laws, Chairman of the Legal Commission, Associate Professor at the University of Geneva, Vice-President (1967) Mr. HARALD HUBER, Doctor of Laws, Federal Court Judge, Vice-President (1969) Mr. HANS BACHMANN, Doctor of Laws, Director of Finance of Winterthur· (1958) Mrs. DENISE BINDSCHEDLER-ROBERT, Doctor of Laws, Professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva (1967) Mr. MARCEL A. NAVILLE, Master of Arts, ICRC President from 1969 to 1973 (1967) Mr. JACQUES F. DE ROUGEMONT, Doctor of Medicine (1967) Mr. ROGER GALLOPIN, Doctor of Laws, former ICRC Director-General (1967) Mr. WALDEMAR JUCKER, Doctor of Laws, Secretary, Union syndicale suisse (1967) Mr. VICTOR H. UMBRICHT, Doctor of Laws, Managing Director (1970) Mr. PIERRE MICHELI, Bachelor of Laws, former Ambassador (971) Mr. GILBERT ETIENNE, Professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies and at the Institut d'etudes du developpement, Geneva (1973) Mr. ULRICH MIDDENDORP, Doctor of Medicine, head of surgical department of the Cantonal Hospital, Winterthur (1973) Miss MARION ROTHENBACH, Master of Social Work (University of Michigan), Reader at the Ecole des Sciences sociales et politiques of the University of Lausanne (1973) Mr. HANS PETER TSCHUDI, Doctor of Laws, former Swiss Federal Councillor (1973) Mr. -

Hendrik Conscience

Hendrik Conscience Bladzijden uit de Roman van een Romancier Marcel Lambin Marcel Lambin Hendrik Conscience Bladzijden uit de Roman van een Romancier WOORD VOORAF Over het werk en het leven van Hendrik Conscience is reeds zoveel geschreven dat men zich afvraagt hoe het mogelijk is er nog een boek aan to wijden. Tijdens zijn laatste levensjaren en onmiddellijk na zijn overlijden (10 september 1883) werden uitvoerige levensoverzichten gepubliceerd . In 1912, ter gelegenheid van het eeuw f eest van zijn geboorte (3 december) werden andermaal een massa bijzonderheden verzameld en uitgegeven . De jongste jaren hee f t August Keersmaekers zich zeer verdienstelijk gemaakt door het publiceren van bijzonderheden uit het leven van de man die zijn yolk leerde lezen ~ . Uit andere studien kan men vernemen welke de verhouding is van de Conscience-romans tot het echte volksleven. Na de studie van Al f ons De Cock in 1913 kwam het systematisch onderzoek van A . Van Hageland (1953). Wij waarderen echter nog het meest wat Remi Sterkens schreef over Conscience en het Kempische volksleven . Op de vraag o f het yolk Conscience nog leest bee ft een openbaar onderzoek door studio Antwerpen van het N.I.R. (1953) uitsluitsel gegeven. De Leeuw van Vlaanr deren kwam op de vijfde plaats nadart 11 .250 antwoor- den van luisteraars hun voorkeur voor een Vlaams boek hadden later kennen . Het kwam na De Witte, Pallieter, De Vlasschaard, maar voor werk van Walschap, Em. Van Hemeldonck, Lode Zielens en Marnix Gijsen . Wij naderen stilaan een nieuw Conscience-jaar : de herdenking van de honderdste verjaring van zijn over- lijden.