Homelab 2 [Solutions]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sitaram Asur, B.E., M.Sc. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Prof. Srinivasan Parthasarathy, Adviser Prof. Gagan Agrawal Adviser Prof. P. Sadayappan Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering c Copyright by Sitaram Asur 2009 ABSTRACT Data originating from many different real-world domains can be represented mean- ingfully as interaction networks. Examples abound, ranging from gene expression networks to social networks, and from the World Wide Web to protein-protein inter- action networks. The study of these complex networks can result in the discovery of meaningful patterns and can potentially afford insight into the structure, properties and behavior of these networks. Hence, there is a need to design suitable algorithms to extract or infer meaningful information from these networks. However, the challenges involved are daunting. First, most of these real-world networks have specific topological constraints that make the task of extracting useful patterns using traditional data mining techniques difficult. Additionally, these networks can be noisy (containing unreliable interac- tions), which makes the process of knowledge discovery difficult. Second, these net- works are usually dynamic in nature. Identifying the portions of the network that are changing, characterizing and modeling the evolution, and inferring or predict- ing future trends are critical challenges that need to be addressed in the context of understanding the evolutionary behavior of such networks. To address these challenges, we propose a framework of algorithms designed to detect, analyze and reason about the structure, behavior and evolution of real-world interaction networks. -

Experiment 12

Experiment 12 Velocity and Propagation of Waves 12.1 Objective To use the phenomenon of resonance to determine the velocity of the propagation of waves in taut strings and wires. 12.2 Discussion Any medium under tension or stress has the following property: disturbances, motions of the matter of which the medium consists, are propagated through the medium. When the disturbances are periodic, they are called waves, and when the disturbances are simple harmonic, the waves are sinusoidal and are characterized by a common wavelength and frequency. The velocity of propagation of a disturbance, whether or not it is periodic, depends generally upon the tension or stress in the medium and on the density of the medium. The greater the stress: the greater the velocity; and the greater the density: the smaller the velocity. In the case of a taut string or wire, the velocity v depends upon the tension T in the string or wire and the mass per unit length µ of the string or wire. Theory predicts that the relation should be T v2 = (12.1) µ Most disturbances travel so rapidly that a direct determination of their velocity is not possible. However, when the disturbance is simple harmonic, the sinusoidal character of the waves provides a simple method by which the velocity of the waves can be indirectly determined. This determination involves the frequency f and wavelength λ of the wave. Here f is the frequency of the simple harmonic motion of the medium and λ is from any point of the wave to the next point of the same phase. -

Tuning a Guitar to the Harmonic Series for Primer Music 150X Winter, 2012

Tuning a guitar to the harmonic series For Primer Music 150x Winter, 2012 UCSC, Polansky Tuning is in the D harmonic series. There are several options. This one is a suggested simple method that should be simple to do and go very quickly. VI Tune the VI (E) low string down to D (matching, say, a piano) D = +0¢ from 12TET fundamental V Tune the V (A) string normally, but preferably tune it to the 3rd harmonic on the low D string (node on the 7th fret) A = +2¢ from 12TET 3rd harmonic IV Tune the IV (D) string a ¼-tone high (1/2 a semitone). This will enable you to finger the 11th harmonic on the 5th fret of the IV string (once you’ve tuned). In other words, you’re simply raising the string a ¼-tone, but using a fretted note on that string to get the Ab (11th harmonic). There are two ways to do this: 1) find the 11th harmonic on the low D string (very close to the bridge: good luck!) 2) tune the IV string as a D halfway between the D and the Eb played on the A string. This is an approximation, but a pretty good and fast way to do it. Ab = -49¢ from 12TET 11th harmonic III Tune the III (G) string to a slightly flat F# by tuning it to the 5th harmonic of the VI string, which is now a D. The node for the 5th harmonic is available at four places on the string, but the easiest one to get is probably at the 9th fret. -

Guitar Harmonics - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Guitar Harmonics from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

3/14/2016 Guitar harmonics - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Guitar harmonics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A guitar harmonic is a musical note played by preventing or amplifying vibration of certain overtones of a guitar string. Music using harmonics can contain very high pitch notes difficult or impossible to reach by fretting. Guitar harmonics also produce a different sound quality than fretted notes, and are one of many techniques used to create musical variety. Contents Basic and harmonic oscillations of a 1 Technique string 2 Overtones 3 Nodes 4 Intervals 5 Advanced techniques 5.1 Pinch harmonics 5.2 Tapped harmonics 5.3 String harmonics driven by a magnetic field 6 See also 7 References Technique Harmonics are primarily generated manually, using a variety of techniques such as the pinch harmonic. Another method utilizes sound wave feedback from a guitar amplifier at high volume, which allows for indefinite vibration of certain string harmonics. Magnetic string drivers, such as the EBow, also use string harmonics to create sounds that are generally not playable via traditional picking or fretting techniques. Harmonics are most often played by lightly placing a finger on a string at a nodal point of one of the overtones at the moment when the string is driven. The finger immediately damps all overtones that do not have a node near the location touched. The lowest-pitch overtone dominates the resulting sound. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guitar_harmonics 1/6 3/14/2016 Guitar harmonics - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Overtones When a guitar string is plucked normally, the ear tends to hear the fundamental frequency most prominently, but the overall sound is also 0:00 MENU colored by the presence of various overtones (integer multiples of the Tuning a guitar using overtones fundamental frequency). -

The Physics of a Longitudinally Vibrating “Singing” Metal Rod

UIUC Physics 193/406 Physics of Music/Musical Instruments The Physics of a Longitudinally Vibrating Metal Rod The Physics of a Longitudinally Vibrating “Singing” Metal Rod: A metal rod (e.g. aluminum rod) a few feet in length can be made to vibrate along its length – make it “sing” at a characteristic, resonance frequency by holding it precisely at its mid-point with thumb and index finger of one hand, and then pulling the rod along its length, toward one of its ends with the thumb and index finger of the other hand, which have been dusted with crushed violin rosin, so as to obtain a good grip on the rod as it is pulled. L L L L/2 L/2 Pull on rod here along its length Hold rod here with thumb with violin rosin powdered thumb and index finger of one hand and index finger of other hand, stretching the rod The pulling motion of the thumb and index finger actually stretches the rod slightly, giving it potential energy – analogous to the potential energy associated with stretching a spring along its length, or a rubber band. The metal rod is actually an elastic solid – elongating slightly when pulled! Pulling on the rod in this manner excites the rod, causing both of its ends to simultaneously vibrate longitudinally, back and forth along its length at a characteristic resonance frequency known as its fundamental frequency, f1. For an excited aluminum rod of length, L ~ 2 meters, it is thus possible that at one instant in time both ends of the rod will be extended a small distance, L ~ 1 mm beyond the normal, (i.e. -

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques JULY 2018 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release: distribution is unlimited. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil), and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard) *TC 1-19.30 (TC 12-43) Training Circular Headquarters No. 1-19.30 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 25 July 2018 Percussion Techniques Contents Page PREFACE................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... xi Chapter 1 BASIC PRINCIPLES OF PERCUSSION PLAYING ................................................. 1-1 History ........................................................................................................................ 1-1 Definitions .................................................................................................................. 1-1 Total Percussionist .................................................................................................... 1-1 General Rules for Percussion Performance .............................................................. 1-2 Chapter 2 SNARE DRUM .......................................................................................................... 2-1 Snare Drum: Physical Composition and Construction ............................................. -

Fingerboard Geography and Harmonics Robert Battey

CELLOSPEAK 2021 Fingerboard Geography and Harmonics Robert Battey 1. The three data sets every capable cellist must know: (a) Names & sizes of intervals, e.g., “a step and a half is called a ‘Minor Third.’” (b) Being able to recognize intervals on the printed page (c) Knowing which fingering combinations (including across strings) result in which intervals, e.g., “2 on the lower string and 3 on the higher string produces a Minor Sixth.” Some cellists learn this through formal theory classes; most just absorb it up slowly and piecemeal through experience. But the fingerboard will always be a gauzy mystery (other than in first position) until you have a grasp of these three data sets. There are many good on-line theory courses, this being one: Musictheory.net/lessons Scroll down to the “Intervals” lessons and try them out. 2. Locating positions and notes (a) The first five (of 12) positions are located through percussive striking of the octave note This can be done on any of the top three strings, with any finger. The sympathetic vibration of the lower string tells you if/when you’re in tune. Copyright ©Robert Battey 2021 (b) Any note with any finger in any of the first five positions can be securely located using this method. From your target note, determine the closest percussive octave note (which may be on a different string), and which finger to use: (c) The next seven positions are all located via their relationship to the thumb. We all know how to find “fourth” position – thumb in the crotch of the neck, 1 st finger right on top of it. -

Standing Waves on a String PURPOSE

San Diego Miramar College Physics 197 NAME: _______________________________________ DATE: _________________________ LABORATORY PARTNERS : ______________________________________________________ Standing Waves on a String PURPOSE: To study the relationship among stretching force (FT), wavelength (흺), vibrational frequency (f), linear mass density (µ), and wave velocity (v) in a vibrating string; to observe standing waves and the harmonic frequencies of a stretched string. THEORY: Standing waves can be produced when two waves of identical wavelength, velocity, and amplitude are traveling in opposite directions through the same medium. Standing waves can be established using a stretched string to create a train of waves, set up by a vibrating body, and reflected at the end of the string. Newly generated waves will interfere with the old reflected waves. If the conditions are right, then a standing wave pattern will be created. A Stretched string has many modes of vibration, i.e. standing waves. It may vibrate as a single segment; its length is then equal to one half of the wavelength of the vibrations produced. It may also vibrate in two segments, with a node at each end in the middle; the wavelength produced is then equal to the length of the string. It may also vibrate in a larger number of segments. In every case, the length of the string is some integer multiple of half wavelengths. So, if a string is stretched between two fixed points, the ends are constrained not to move; hence, these are the nodes. In a standing wave the nodes, or the points that do not vibrate, occur every half the wavelength; thus, the ends of the string must correspond to nodes and the whole length of the string must accommodate an integer nymber of half wavelengths. -

Standing Waves When They Superpose

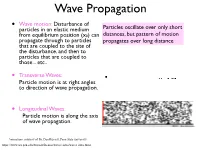

Wave Propagation • Wave motion: Disturbance of particles in an elastic medium Particles oscillate over only short from equilibrium position (x0) can distances, but pattern of motion propagate through to particles propagates over long distance that are coupled to the site of the disturbance, and then to particles that are coupled to those... etc.. • Transverse Waves: Particle motion is at right angles to direction of wave propagation. • Longitudinal Waves: Particle motion is along the axis of wave propagation. Animations courtesy of Dr. Dan Russell, Penn State university https://www.acs.psu.edu/drussell/Demos/waves-intro/waves-intro.html Longitudinal Sound Waves Sinusoidal oscillation of air molecule positions at any given point in space results in sinusoidal oscillation of pressure between pressure maxima and minima (rarefactions). Sinusoidal oscillation in particle velocity also results--90˚ out of • phase with pressure. • Due to propagation sinusoidal pattern can also be seen in space. Increased Zero λ Velocity Decreased Velocity Velocity Wavelength (λ) is the distance in space between successive maxima (or minima) Wavelength and frequency Speed of Sound (c): • Pressure wave propagates through air at 34,029 cm/sec • Since distance traveled = velocity * elapsed time • if T is the period of one sinusoidal oscillation, then: λ = cT • And since T=1/f : λ = c/f Superposition of waves Waves traveling in opposite directions superpose when they coincide, then continue traveling. Oscillations of the same frequency, and same amplitude form standing waves when they superpose. •Don’t travel, only change in amplitude over time. •Nodes: no change in position. •Anti-nodes: maximal change in position. -

The Sounds of Music: Science of Musical Scales∗ 1

SERIES ARTICLE The Sounds of Music: Science of Musical Scales∗ 1. Human Perception of Sound Sushan Konar Both, human appreciation of music and musical genres tran- scend time and space. The universality of musical genres and associated musical scales is intimately linked to the physics of sound, and the special characteristics of human acoustic sensitivity. In this series of articles, we examine the science underlying the development of the heptatonic scale, one of the most prevalent scales of the modern musical genres, both western and Indian. Sushan Konar works on stellar compact objects. She Introduction also writes popular science articles and maintains a Fossil records indicate that the appreciation of music goes back weekly astrophysics-related blog called Monday Musings. to the dawn of human sentience, and some of the musical scales in use today could also be as ancient. This universality of musi- cal scales likely owes its existence to an amazing circularity (or periodicity) inherent in human sensitivity to sound frequencies. Most musical scales are specific to a particular genre of music, and there exists quite a number of them. However, the ‘hepta- 1 1 tonic’ scale happens to have a dominating presence in the world Having seven base notes. music scene today. It is interesting to see how this has more to do with the physics of sound and the physiology of human auditory perception than history. We shall devote this first article in the se- ries to understand the specialities of human response to acoustic frequencies. Human ear is a remarkable organ in many ways. The range of hearing spans three orders of magnitude in frequency, extending Keywords from ∼20 Hz to ∼20,000 Hz (Figure 1) even though the sensitivity String vibration, beat frequencies, consonance-dissonance, pitch, tone. -

INTRODUCTION to COMSOL Multiphysics Introduction to COMSOL Multiphysics

INTRODUCTION TO COMSOL Multiphysics Introduction to COMSOL Multiphysics © 1998–2020 COMSOL Protected by patents listed on www.comsol.com/patents, and U.S. Patents 7,519,518; 7,596,474; 7,623,991; 8,457,932; 9,098,106; 9,146,652; 9,323,503; 9,372,673; 9,454,625; 10,019,544; 10,650,177; and 10,776,541. Patents pending. This Documentation and the Programs described herein are furnished under the COMSOL Software License Agreement (www.comsol.com/comsol-license-agreement) and may be used or copied only under the terms of the license agreement. COMSOL, the COMSOL logo, COMSOL Multiphysics, COMSOL Desktop, COMSOL Compiler, COMSOL Server, and LiveLink are either registered trademarks or trademarks of COMSOL AB. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners, and COMSOL AB and its subsidiaries and products are not affiliated with, endorsed by, sponsored by, or supported by those trademark owners. For a list of such trademark owners, see www.comsol.com/ trademarks. Version: COMSOL 5.6 Contact Information Visit the Contact COMSOL page at www.comsol.com/contact to submit general inquiries, contact Technical Support, or search for an address and phone number. You can also visit the Worldwide Sales Offices page at www.comsol.com/contact/offices for address and contact information. If you need to contact Support, an online request form is located at the COMSOL Access page at www.comsol.com/support/case. Other useful links include: • Support Center: www.comsol.com/support • Product Download: www.comsol.com/product-download • Product Updates: www.comsol.com/support/updates •COMSOL Blog: www.comsol.com/blogs • Discussion Forum: www.comsol.com/community •Events: www.comsol.com/events • COMSOL Video Gallery: www.comsol.com/video • Support Knowledge Base: www.comsol.com/support/knowledgebase Part number: CM010004 Contents Introduction . -

BGM61 December 2010

Barefaced Bass But this goes to 11... But this goes to 11… welcome to the world of bass rigs. about the author ast time we veered off the frequency (pitch), plus a collection (point of maximum movement) path of amplification and of percussive non-harmonic at the 12th fret. So a pickup at c. alexander went back to looking at overtones (string noise, fret rattle the 12th fret would pick up the claBer what happens when you and buzz, finger/pick-on-string 1st harmonic (aka ‘fundamental’) Alex first picked up a bass Lpluck a string. As most of us play sounds etc). The more that each very loudly. The 2nd harmonic has when studying engineering at basses with traditional magnetic component of the sound causes a node at the nut, 12th fret and university, and his quest for sonic pickups, we shall have a look at the string to move within the bridge, and antinodes at the 5th perfection led him to found how they turn these vibrations into aperture of the pickup, the more of fret and 24th fret, so our 12th-fret Barefaced Audio, while also a signal that we can amplify. that component you hear. pickup won’t really hear the 2nd leading The Reluctant, an alt-ska/ A single-coil pickup has a narrow Right, let’s look at the open strings harmonic. The 3rd harmonic has a funk outfit. aperture which picks up the and imagine that our pickup is node at the nut, 7th fret, 19th fret movement of the string directly at the 12th fret (I know it can’t be and bridge, and antinodes at the above it.