V41n4p34.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mississippi Kite (Ictinia Mississippiensis)

Mississippi Kite (Ictinia mississippiensis) NMPIF level: Species Conservation Concern, Level 2 (SC2) NMPIF assessment score: 15 NM stewardship responsibility: Low National PIF status: No special status New Mexico BCRs: 16, 18, 35 Primary breeding habitat(s): Urban (southeast plains) Other habitats used: Agricultural, Middle Elevation Riparian Summary of Concern Mississippi Kite is a migratory raptor that has successfully colonized urban habitats (parks, golf courses, residential neighborhoods) in the western portion of its breeding range over the last several decades. Little is known about species ecology outside of the breeding season and, despite stable or increasing populations at the periphery of its range, it remains vulnerable due to its small population size. Associated Species Cooper’s Hawk, Ring-necked Pheasant, Mourning Dove, American Robin Distribution Mississippi Kite is erratically distributed across portions of the east and southeast, the southern Great Plains, and the southwest, west to central Arizona and south to northwest Chihuahua. It is most abundant in areas of the Gulf Coast, and in the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles. The species is a long- distance migrant, wintering in Argentina, Paraguay, and perhaps other locations in South America. In New Mexico, Mississippi Kite is most common in cites and towns of the southeast plains. It is also present in the Middle Rio Grande valley north to Corrales, and the Pecos River Valley north to Fort Sumner and possibly Puerto de Luna (Parker 1999, Parmeter et al. 2002). Ecology and Habitat Requirements Mississippi Kite occupies different habitats in different parts of its range, including mature hardwood forests in the southeast, rural woodlands in mixed and shortgrass prairie in the Great Plains, and mixed riparian woodlands in the southwest. -

Birds Versus Bats: Attack Strategies of Bat-Hunting Hawks, and the Dilution Effect of Swarming

Supplementary Information Accompanying: Birds versus bats: attack strategies of bat-hunting hawks, and the dilution effect of swarming Caroline H. Brighton1*, Lillias Zusi2, Kathryn McGowan2, Morgan Kinniry2, Laura N. Kloepper2*, Graham K. Taylor1 1Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PS, UK. 2Department of Biology, Saint Mary’s College, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA. *Correspondence to: [email protected] This file contains: Figures S1-S2 Tables S1-S3 Supplementary References supporting Table S1 Legend for Data S1 and Code S1 Legend for Movie S1 Data S1 and Code S1 implementing the statistical analysis have been uploaded as Supporting Information. Movie S1 has been uploaded to figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11823393 Figure S1. Video frames showing examples of attacks on lone bats and the column. (A,B) Attacks on the column of bats, defined as an attack on one or more bats within a cohesive group of individuals all flying in the same general direction. (C-E) Attacks on a lone bat (circled red), defined as an attack on an individual that appeared to be flying at least 1m from the edge of the column, and typically in a different direction to the swarm. (F) If an attack occurred in a volume containing many bats, but with no coherent flight direction, then this was also categorised as an attack on a lone bat, rather than as an attack on the swarm. Figure S2 Video frames used to estimate the proportion of bats meeting the criteria for classification as lone bats. -

Introduction to Tropical Biodiversity, October 14-22, 2019

INTRODUCTION TO TROPICAL BIODIVERSITY October 14-22, 2019 Sponsored by the Canopy Family and Naturalist Journeys Participants: Linda, Maria, Andrew, Pete, Ellen, Hsin-Chih, KC and Cathie Guest Scientists: Drs. Carol Simon and Howard Topoff Canopy Guides: Igua Jimenez, Dr. Rosa Quesada, Danilo Rodriguez and Danilo Rodriguez, Jr. Prepared by Carol Simon and Howard Topoff Our group spent four nights in the Panamanian lowlands at the Canopy Tower and another four in cloud forest at the Canopy Lodge. In very different habitats, and at different elevations, conditions were optimal for us to see a great variety of birds, butterflies and other insects and arachnids, frogs, lizards and mammals. In general we were in the field twice a day, and added several night excursions. We also visited cultural centers such as the El Valle Market, an Embera Village, the Miraflores Locks on the Panama Canal and the BioMuseo in Panama City, which celebrates Panamanian biodiversity. The trip was enhanced by almost daily lectures by our guest scientists. Geoffroy’s Tamarin, Canopy Tower, Photo by Howard Topoff Hot Lips, Canopy Tower, Photo by Howard Topoff Itinerary: October 14: Arrival and Orientation at Canopy Tower October 15: Plantation Road, Summit Gardens and local night drive October 16: Pipeline Road and BioMuseo October 17: Gatun Lake boat ride, Emberra village, Summit Ponds and Old Gamboa Road October 18: Gamboa Resort grounds, Miraflores Locks, transfer from Canopy Tower to Canopy Lodge October 19: La Mesa and Las Minas Roads, Canopy Adventure, Para Iguana -

The Order Falconiformes in Cuba: Status, Distribution, Migration and Conservation

Chancellor, R. D. & B.-U. Meyburg eds. 2004 Raptors Worldwide WWGBP/MME The order Falconiformes in Cuba: status, distribution, migration and conservation Freddy Rodriguez Santana INTRODUCTION Fifteen species of raptors have been reported in Cuba including residents, migrants, transients, vagrants and one endemic species, Gundlach's Hawk. As a rule, studies on the biology, ecology and migration as well as conservation and management actions of these species have yet to be carried out. Since the XVI century, the Cuban archipelago has lost its natural forests gradually to nearly 14 % of the total area in 1959 (CIGEA 2000). Today, Cuba has 20 % of its territory covered by forests (CIGEA op. cit) and one of the main objectives of the Cuban environmental laws is to protect important areas for biodiversity as well as threatened, migratory, commercial and endemic species. Nevertheless, the absence of raptor studies, poor implementation of the laws, insufficient environmental education level among Cuban citizens and the bad economic situation since the 1990s continue to threaten the population of raptors and their habitats. As a result, the endemic Gundlach's Hawk is endangered, the resident Hook-billed Kite is almost extirpated from the archipelago, and the resident race of the Sharp-shinned Hawk is also endangered. Studies on these species, as well as conservation and management plans based on sound biological data, are needed for the preservation of these and the habitats upon which they depend. I offer an overview of the status, distribution, threats, migration and conservation of Cuba's Falconiformes. MATERIALS AND METHODS For the status and distribution of the Falconiformes in Cuba, I reviewed the latest published literature available as well as my own published and unpublished data. -

The Kites of the Genus Ictinia

THE WILSON BULLETIN A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OF ORNITHOLOGY Published by the Wilson Ornithological Club MARCH, 1944 THE KITES OF THE GENUS ICTINIA BY GEORGE MIKSCH SUTTON RE the Mississippi Kite and Plumbeous Kite distinct species,or are A they geographical races of the same bird? Twenty years ago, when I first compared specimens of the two forms, I was so impressed with certain differences between them that it did not occur to me to question the judgment of those who had accorded them full’ specific rank. At that time I had not seen either in life, had not examined either eggs or young birds, and did not know enough about taxonomy to be concerned with the validity of such phylogenetic concepts as might be embodied in, or proclaimed by, their scientific names, Today I am much better acquainted with these two kites. I have spent weeks on end with the former in western Oklahoma (Sutton, 1939:41-53) and have encountered the latter briefly in southwestern Tamaulipas, at the northern edge of its range (Sutton and Pettingill, 1942: 8). I have handled the skins in several of our museums and am convinced that neither form has a single morphological character wholly its own. I have made a point of observing both birds critically in life, have heard their cries, noted carefully the colors of their fleshy parts, painted them from freshly killed specimens, skinned them, and examined their stomach contents. All this, together with what I have learned from the literature concerning the distribution and nesting habits of the Plumbeous Kite, convinces me that the two birds are conspecific. -

A Microscopic Analysis of the Plumulaceous Feather Characteristics of Accipitriformes with Exploration of Spectrophotometry to Supplement Feather Identification

A MICROSCOPIC ANALYSIS OF THE PLUMULACEOUS FEATHER CHARACTERISTICS OF ACCIPITRIFORMES WITH EXPLORATION OF SPECTROPHOTOMETRY TO SUPPLEMENT FEATHER IDENTIFICATION by Charles Coddington A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Biology Committee: __________________________________________ Dr. Larry Rockwood, Thesis Director __________________________________________ Dr. David Luther, Committee Member __________________________________________ Dr. Carla J. Dove, Committee Member __________________________________________ Dr. Ancha Baranova, Committee Member __________________________________________ Dr. Iosif Vaisman, Director, School of Systems Biology __________________________________________ Dr. Donna Fox, Associate Dean, Office of Student Affairs & Special Programs, College of Science __________________________________________ Dr. Peggy Agouris, Dean, College of Science Date: _____________________________________ Summer Semester 2018 George Mason University Fairfax, VA A Microscopic Analysis of the Plumulaceous Feather Characteristics of Accipitriformes with Exploration of Spectrophotometry to Supplement Feather Identification A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at George Mason University by Charles Coddington Bachelor of Arts Connecticut College 2013 Director: Larry Rockwood, Professor/Chair Department of Biology Summer Semester 2019 George Mason University Fairfax, VA -

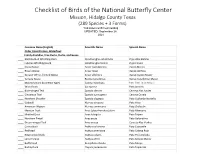

Bird Checklist

Checklist of Birds of the National Butterfly Center Mission, Hidalgo County Texas (289 Species + 3 Forms) *indicates confirmed nesting UPDATED: September 28, 2021 Common Name (English) Scientific Name Spanish Name Order Anseriformes, Waterfowl Family Anatidae, Tree Ducks, Ducks, and Geese Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Pijije Alas Blancas Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Pijije Canelo Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ganso Blanco Ross's Goose Anser rossii Ganso de Ross Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Ganso Careto Mayor Canada Goose Branta canadensis Ganso Canadiense Mayor Muscovy Duck (Domestic type) Cairina moschata Pato Real (doméstico) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Pato Arcoíris Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cerceta Alas Azules Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cerceta Canela Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Pato Cucharón Norteño Gadwall Mareca strepera Pato Friso American Wigeon Mareca americana Pato Chalcuán Mexican Duck Anas (platyrhynchos) diazi Pato Mexicano Mottled Duck Anas fulvigula Pato Tejano Northern Pintail Anas acuta Pato Golondrino Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Cerceta Alas Verdes Canvasback Aythya valisineria Pato Coacoxtle Redhead Aythya americana Pato Cabeza Roja Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Pato Pico Anillado Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Pato Boludo Menor Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Pato Monja Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Pato Tepalcate Order Galliformes, Upland Game Birds Family Cracidae, Guans and Chachalacas Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula Chachalaca Norteña Family Odontophoridae, -

The Mississippi Kite

THE MISSISSIPPI KITE Vol. 47 (2) December 2017 THE MISSISSIPPI KITE The Mississippi Kite is sent to all members of the Mississippi Ornithological Society not in arrears of dues. Send change of address, requests for back issues, and claims for undelivered or defective copies to the Membership Committee Chair, Gene Knight, at 79 Hwy. 9 W., Oxford, MS 38655. Information for Authors The Mississippi Kite publishes original articles that advance the study of birdlife in the state of Mississippi. Submission of articles describing species occurrence and distribution, descriptions of unusual birds or behaviors, notes on the identification of Mississippi birds, as well as scientific studies from all fields of ornithology are encouraged. Submit all manuscripts in either a paper copy or digital copy format to the Editor, Nick Winstead, at Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, 2148 Riverside Dr., Jackson, MS 39202 or through email at [email protected]. COPY – Paper copy manuscripts should be typed and double-spaced throughout. Digital copy manuscripts should be prepared using 12 pt. Times New Roman font. If possible, please submit digital files in Microsoft Word. Handwritten manuscripts may also be accepted, but please contact the editor prior to submission. STYLE – For questions of style consult previous issues of The Mississippi Kite. Manuscripts should include a title, names and addresses of all authors, text, and where applicable, literature cited, tables, figures, and figure legends. Number all pages in the upper right-hand corner. Avoid footnotes. LITERATURE CITED – List all references cited in the text alphabetically by the author’s last name in the Literature Cited section. -

Breeding Ecology of the Mississippi Kite in Arizona

Condor85:200-207 0 The Cooper Ornithological Sowsty 1983 BREEDING ECOLOGY OF THE MISSISSIPPI KITE IN ARIZONA RICHARD L. GLINSKI AND ROBERT D. OHMART ABSTRACT. -The Mississippi Kite (Zctinia mississippiensis)recently has ex- tended its breeding range into the southwestern United States and was first re- corded nesting in Arizona in 1970. Approximately 25 regularly active nesting sites occur in Arizona in riparian forest-scrublandhabitat along the tributaries of the Gila River. Nesting habitat consisted of a structurally diverse (patchy) ar- rangement of cottonwood (Populusfiemontiz~trees and salt cedar (Tamarix chi- nensis)understory. Cicadas, the principal prey of the kites studied, were captured frequently (4 1% of all prey captures)by hawking from cottonwood percheswithin 150 m of nests. Vegetation patchinessfacilitated foraging and accounted for 7 1% of the variation in reproduction. Increased vegetation diversity in the more tra- ditional breeding areasof the Great Plains and in migration and wintering habitats may have enhanced foraging, reproduction, and survival of kites, and may help to explain the recent population increase. Most nest sites were distributed among four groups. No movement between groups was noted during any one nesting season.Most adult kites attempted to nest, but up to 52% of all nesting attempts failed during courtship and nest- building (44% of all failures), incubation (40%), and nestling (16%) stages.Re- productive successwas 0.60 fledglings per nesting attempt, similar to that esti- mated for kites in the Great Plains. Apparently, reproduction at a nest was not enhanced by close proximity to another active kite nest. The Mississippi Kite (Zctinia mississippiensis) (vegetation classification after Brown et al. -

New Distributional and Temporal Bird Records from Chihuahua, Mexico

Israel Moreno-Contreras et al. 272 Bull. B.O.C. 2016 136(4) New distributional and temporal bird records from Chihuahua, Mexico by Israel Moreno-Contreras, Fernando Mondaca, Jaime Robles-Morales, Manuel Jurado, Javier Cruz, Alonso Alvidrez & Jaime Robles-Carrillo Received 25 May 2016 Summary.—We present noteworthy records from Chihuahua, northern Mexico, including several first state occurrences (e.g. White Ibis Eudocimus albus, Red- shouldered Hawk Buteo lineatus) or species with very few previous state records (e.g. Tricoloured Heron Egretta tricolor, Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula). We also report the first Chihuahuan records of Red-tailed Hawk Buteo jamaicensis harlani and ‘White-winged’ Dark-eyed Junco Junco hyemalis aikeni (the latter only the second Mexican record). Other records improve our knowledge of the distribution of winter visitors to the Chihuahuan Desert ecoregion that formerly were considered transients, including several parulids. Our field work has also improved knowledge of the distribution of certain Near Threatened (e.g. Snowy Plover Charadrius nivosus) and Vulnerable species (e.g. Pinyon Jay Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus). We also confirmed various breeding localities for Yellow-crowned Night Heron Nyctanassa violacea in Chihuahua. The avian diversity of Mexico encompasses 95 families, 493 genera and 1,150 species following IOC taxonomy (cf. Navarro-Sigüenza et al. 2014) or c.11% of total avian richness worldwide. Mexico is ranked as the 11th most important country in terms of bird species richness and fourth in the proportion of endemic species (Navarro-Sigüenza et al. 2014). However, Chihuahua—the largest Mexican state—is poorly surveyed ornithologically, mostly at sites in and around the Sierra Madre Occidental (e.g., Stager 1954, Miller et al. -

The Mississippi Kite in Spring (With Eight Ills.)

THE CONDOR VOLUME XL1 MARCH-APRIL, 1939 NUMBER 2 THE MISSISSIPPI KITE IN SPRING WITH EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS By GEORGE MIKSCH SUTTON The Mississippi Kite (Zctinia misisippe’erasis)is a well known summer resident in parts of western Oklahoma. While not found in the Panhandle (save at the extreme eastern end) it is widely distributed throughout the western half of the main body of the State, in some sections being downright abundant. \ Eager to become acquainted with this beautiful bird, I went to Oklahoma in the spring of 1936, establishing headquarters at Arnett, Ellis County, on May 7. Here I remained almost continuously for the following six weeks, devoting a large part of my time to observing Kites. I used an automobile, driving from fifteen to fifty miles a day in reaching various parts of the County. Nests were not difficult to locate as a rule, owing to the fact that trees were scarce. In 1937, Messrs. John B. Semple, Karl Haller, Leo A. Luttringer, Jr., and myself again visited western Oklahoma, encountering the Kites in the vicinity of Indiahoma, Comanche County, on May 7 and 8; near Cheyenne, Roger Mills County, from May 9 to 15; in eastern Beaver County from May 16 to 18; and again (from May 26 to 31) in the vicinity of Arnett, Ellis County. The following paper deals, then, with the earlier part of the Kite’s nesting season -the return from the south, the selection and defense of the nesting-territory, the build- ing of the nest, the laying and incubating of the eggs. -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species.