AMERICAN NEGRO EXHIBIT" of 1900 by Miles Everett Travis A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How North Carolina's Black Politicians and Press Narrated and Influenced the Tu

D. SHARPLEY 1 /133 Black Discourses in North Carolina, 1890-1902: How North Carolina’s Black Politicians and Press Narrated and Influenced the Tumultuous Era of Fusion Politics By Dannette Sharpley A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors Department of History, Duke University Under the advisement of Dr. Nancy MacLean April 13, 2018 D. SHARPLEY 2 /133 Acknowledgements I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to write an Honors Thesis in the History Department. When I returned to school after many years of separation, I was prepared for challenging work. I expected to be pushed intellectually and emotionally. I expected to struggle through all-nighters, moments of self-doubt, and even academic setbacks. I did not, however, imagine that I could feel so passionate or excited about what I learned in class. I didn’t expect to even undertake such a large project, let alone arrive at the finish line. And I didn’t imagine the sense of accomplishment at having completed something that I feel is meaningful beyond my own individual education. The process of writing this thesis has been all those things and more. I would first like to thank everyone at the History Department who supports this Honors Distinction program, because this amazing process would not be possible without your work. Thank you very much to Dr. Nancy MacLean for advising me on this project. It was in Professor MacLean’s History of Modern Social Movements class that I became obsessed with North Carolina’s role in the Populist movement of the nineteenth, thus beginning this journey. -

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

“The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell” JIM CROW AND THE EXCLUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS FROM CONGRESS, 1887–1929 On December 5, 1887, for the first time in almost two decades, Congress convened without an African-American Member. “All the men who stood up in awkward squads to be sworn in on Monday had white faces,” noted a correspondent for the Philadelphia Record of the Members who took the oath of office on the House Floor. “The negro is not only out of Congress, he is practically out of politics.”1 Though three black men served in the next Congress (51st, 1889–1891), the number of African Americans serving on Capitol Hill diminished significantly as the congressional focus on racial equality faded. Only five African Americans were elected to the House in the next decade: Henry Cheatham and George White of North Carolina, Thomas Miller and George Murray of South Carolina, and John M. Langston of Virginia. But despite their isolation, these men sought to represent the interests of all African Americans. Like their predecessors, they confronted violent and contested elections, difficulty procuring desirable committee assignments, and an inability to pass their legislative initiatives. Moreover, these black Members faced further impediments in the form of legalized segregation and disfranchisement, general disinterest in progressive racial legislation, and the increasing power of southern conservatives in Congress. John M. Langston took his seat in Congress after contesting the election results in his district. One of the first African Americans in the nation elected to public office, he was clerk of the Brownhelm (Ohio) Townshipn i 1855. -

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THAT OUR GOVERNMENT MAY STAND”: AFRICAN AMERICAN POLITICS IN THE POSTBELLUM SOUTH, 1865-1901 By LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Mia Bay and Ann Fabian and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “That Our Government May Stand”: African American Politics in the Postbellum South, 1865-1913 by LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO Dissertation Director: Mia Bay and Ann Fabian This dissertation provides a fresh examination of black politics in the post-Civil War South by focusing on the careers of six black congressmen after the Civil War: John Mercer Langston of Virginia, James Thomas Rapier of Alabama, Robert Smalls of South Carolina, John Roy Lynch of Mississippi, Josiah Thomas Walls of Florida, and George Henry White of North Carolina. It examines the career trajectories, rhetoric, and policy agendas of these congressmen in order to determine how effectively they represented the wants and needs of the black electorate. The dissertation argues that black congressmen effectively represented and articulated the interests of their constituents. They did so by embracing a policy agenda favoring strong civil rights protections and encompassing a broad vision of economic modernization and expanded access for education. Furthermore, black congressmen embraced their role as national leaders and as spokesmen not only for their congressional districts and states, but for all African Americans throughout the South. -

George Henry White: the American Phoenix

George Henry White: The American Phoenix "This is perhaps the Negroes' temporary farewell to the American Congress, but let me say, Phoenix-like he will rise up some day and come again. These parting words are in behalf of an outraged, heart-broken, bruised and bleeding, but God- fearing people; faithful, industrious, loyal, rising people – full of potential force." ~George Henry White Overview In this lesson students examine the life and career of North Carolina native George Henry White, the last African American Congressman before the Jim Crow Era, as well as the reasons for the decline in African American representation in Congress during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Through examination of Congressional data from the time period, viewing a documentary (optional), analyzing speech excerpts, class discussion, and more, students will gain a comprehensive understanding of the political, cultural and racial realities of the Jim Crow Era. The lesson culminates with an assignment where students are tasked with creating a reelection campaign for White. Grades 8-12 Materials • “George Henry White: American Phoenix” 15-minute documentary; available at http://www.georgehenrywhite.com/ o Teachers can also utilize online information to share with students (via lecture or having them read a handout) at https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/george-henry-white • Computers with internet access for student research (optional) • “African American Members in Congress, 1869 - 1913”, attached (p. 9-10) • “The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell: Jim Crow and the Exclusion of African Americans from Congress, 1887– 1929”, attached (p. 11-12) • “American Phoenix Viewing Guide”, attached (p. 13) • “George Henry White Quotes”, attached (p. -

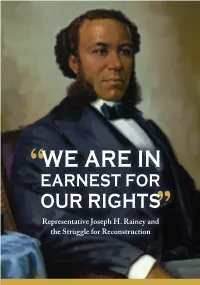

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

When African-Americans Were Republicans in North Carolina, the Target of Suppressive Laws Was Black Republicans. Now That They

When African-Americans Were Republicans in North Carolina, The Target of Suppressive Laws Was Black Republicans. Now That They Are Democrats, The Target Is Black Democrats. The Constant Is Race. A Report for League of Women Voters v. North Carolina By J. Morgan Kousser Table of Contents Section Title Page Number I. Aims and Methods 3 II. Abstract of Findings 3 III. Credentials 6 IV. A Short History of Racial Discrimination in North Carolina Politics A. The First Disfranchisement 8 B. Election Laws and White Supremacy in the Post-Civil War South 8 C. The Legacy of White Political Supremacy Hung on Longer in North Carolina than in Other States of the “Rim South” 13 V. Democratizing North Carolina Election Law and Increasing Turnout, 1995-2009 A. What Provoked H.B. 589? The Effects of Changes in Election Laws Before 2010 17 B. The Intent and Effect of Election Laws Must Be Judged by their Context 1. The First Early Voting Bill, 1993 23 2. No-Excuse Absentee Voting, 1995-97 24 3. Early Voting Launched, 1999-2001 25 4. An Instructive Incident and Out-of-Precinct Voting, 2005 27 5. A Fair and Open Process: Same-Day Registration, 2007 30 6. Bipartisan Consensus on 16-17-Year-Old-Preregistration, 2009 33 VI. Voter ID and the Restriction of Early Voting: The Preview, 2011 A. Constraints 34 B. In the Wings 34 C. Center Stage: Voter ID 35 VII. H.B. 589 Before and After Shelby County A. Process Reveals Intention 37 B. Facts 1. The Extent of Fraud 39 2. -

House Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 167 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MAY 12, 2021 No. 82 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was impacted by horrific events. They pre- I wholeheartedly agree with my called to order by the Speaker pro tem- vent the tragedy from fading from our friend, the chief of police in Chambers- pore (Mr. CORREA). memories by educating the generations burg, and Congress must do our part to f to come, and they highlight the mod- support these heroes. Instead of talk- ern-day implications of such events. ing about defunding the police, we DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO My resolution would provide a day should be working to better train and TEMPORE for slavery remembrance, and the lan- equip law enforcement officers to do The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- guage of the resolution would com- the job that we have entrusted them to fore the House the following commu- memorate the lives of all enslaved peo- do. nication from the Speaker: ple, while condemning the act and the As we move forward, the American WASHINGTON, DC, perpetration as well as perpetuation of people know that Republicans are lead- May 12, 2021. slavery in the United States of Amer- ing commonsense, bipartisan solutions. I hereby appoint the Honorable LUIS J. ica and across the world. For over a year, Senator TIM SCOTT CORREA to act as Speaker pro tempore on The resolution would discuss the and Congressman PETE STAUBER have this day. -

Journalism, Racial Violence, and Political Control in Postbellum North Carolina

ABSTRACT BENTON, ANDREW MORGAN. The Press and the Sword: Journalism, Racial Violence, and Political Control in Postbellum North Carolina. (Under the direction of Dr. Susanna Lee.) Political tension characterized North Carolina in the decades after the Civil War, and the partisan press played a critical role for both parties from the 1860s through the turn of the twentieth century: Republican papers praised the reforms of biracial Republican legislatures while Democratic editors harped on white fears of “negro rule” and black sexual predation. This study analyzes the relationship between press, politics, and violence in postbellum North Carolina through case studies of the 1870 Kirk-Holden War and the so-called Wilmington Race Riot of 1898. My first chapter argues that the Democratic press helped exacerbate the Kirk-Holden War by actively mocking black political aspirations, criticizing Republican leaders such as Holden, and largely ignoring the true nature and scope of the Klan in the 1860s. My second chapter argues that rhetoric played a crucial role in the way the violence in Wilmington transpired and has been remembered, and my conclusion discusses the ways that the press manipulated the public’s historical memory of both tragedies. It is not my intention to argue direct causation between racist rhetoric and racial crimes. Rather, I argue that North Carolina’s partisan press, and especially its Democratic editors, exacerbated pre-existing racial tensions and used images and language to suggest modes of thought—defense of white womanhood, for example—by which white supremacists directed and legitimized violence. The Press and the Sword: Journalism, Racial Violence, and Political Control in Postbellum North Carolina by Andrew Morgan Benton A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: Dr. -

Social Justice and Economic Reparation: African-American Struggles for Equal Opportunity Around the Turn of the Century

NANZAN REVIEW OF AMERICAN STUDIES Volume 31 (2009): 205-217 Proceedings of the NASSS 2009 Literature and Culture I Social Justice and Economic Reparation: African-American Struggles for Equal Opportunity Around the Turn of the Century OKUDA Akiyo KEIO UNIVERSITY Introduction In the history of the United States, one could point to a number of times the country has undertaken restorative measures to right past wrongs. Immediately after the Civil War, Congress, led by radical Republicans, not only abolished slavery but, also ensured freedmen’s full participation in society with the Fourteenth and the Fifteenth Amendments. The Civil Rights Act of the 1960’s attempted to undo the injustice imposed by the post-Reconstruction South that relegated blacks to second-class citizenship. Affirmative action was another policy aimed at restoring social justice. However, what has been missing throughout the entire period is an economic base that would allow black Americans to take full advantage of these measures. Racial equality, reparation advocates claim, is still not a reality today because an economic gap between the races still exists.1 That gap, they claim, can be traced back to the brutal lynchings and whitecappings of the turn of the century that allowed Southern whites to take away black-owned properties by the use of violent force. Why wasn’t there any economic aid to the four million newly freed slaves immediately after the war, nor economic reparations in the following decades? I argue that while black leaders sought political and social justice seriously, they did not seek economic justice because of the precarious position they were in, and because they felt black people needed to claim success in their new role as a free people. -

Lynching: Ida B. Wells-Barnett and the Outrage Over the Frazier Baker

Lynching Ida B. Wells-Barnett and the Outrage over the Frazier Baker Murder By Trichita M. Chestnut Somebody must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning, and it seems to have fallen upon me to do so. The awful death-toll that Judge Lynch is calling every week is appalling, not only because, of the lives it takes, [and] the rank cruelty and outrage to the victims, but because of the prejudice it fosters and the stain it places against the good name of the weak race. The Afro-American is not a bestial race. —Ida B.Wells, preface to Southern Horror n 1898 the Department of Justice was bombarded In southern law, politics, and the economy, the racial with letters concerning a recent lynching in South hierarchy placed African Americans at the bottom and I Carolina.The postmaster of Lake City, Frazier Baker, whites at the top. Many whites believed African and his nearly two-year-old daughter Julia had been killed Americans had a dual nature—“docile and amiable when by a mob in the early hours of February 22.Two of the let- enslaved,ferocious and murderous when free[d].”Senator ters were from Ida B. Wells-Barnett—journalist, author, Benjamin (Ben) R.Tillman of South Carolina proclaimed public speaker, and civil rights activist—who received that the African American man was “a fiend, a wild beast, national and international attention for her efforts to seeking whom he may devour.” Many southern whites expose, educate, and inform the public on the evils and had an acute anxiety over racial purity, and they feared truths of lynching. -

OUR STORIES: a County by County Journey Through East Carolina

OUR STORIES: A County by County Journey Through East Carolina Camden Gates Currituck Sunbury Currituck Hertford St. Peter's Episcopal Church St. Luke's Episcopal Mission Gatesville Elizabeth City St. Mary's Episcopal Church Christ Episcopal Church Ahoskie St. Thomas Episcopal Church Elizabeth City Perquimans Bertie Hertford Roxobel Holy Trinity Episcopal Church Pasquotank St. Mark's Mission Edenton All Saints Episcopal Church Lewiston-Woodville St. Paul's Episcopal Church Grace Episcopal Church Chowan Windsor St. Thomas Episcopal Church Nags Head Columbia St. Andrew's by the Sea Washington St. Andrew's Episcopal Church Martin Roper St. Luke's & St. Anne's Episcopal Church Plymouth Creswell Tyrrell Williamston Grace Episcopal Church Dare Church of the Advent Christ Episcopal Church Galilee Mission Greenville Farmville Belhaven Emmanuel Episcopal Church The Well Episcopal Lutheran Campus Ministry St. James Episcopal Church St. Timothy's Episcopal Church Wayne Washington Hyde Greene St. Paul's Episcopal Church Zion Episcopal Church Bath Goldsboro Pitt Chocowinity St. Thomas Episcopal Church Trinity Episcopal Church St. Peter's Episcopal Church Engelhard St. Francis Episcopal Church St. George's Episcopal Church Grifton St Andrew's Episcopal Church St. John's Episcopal Church St. Stephen's Church Kinston Beaufort Diocesan House Newton Grove Lenoir St. Mary's Episcopal Church Craven La Iglesia de la Sagrada Familia St. Augustine's Episcopal Church Seven Springs New Bern Fayetteville Holy Innocents Episcopal Church St. Cyprian's Episcopal Church Cumberland Trenton Pamlico Grace Episcopal Church Christ Episcopal Church Oriental Hoke Church of the Good Shepherd Jones St. Thomas Episcopal Church St. John's Episcopal Church Clinton St. -

“The Negroes' Temporary Farewell”

“The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell” Jim Crow and the Exclusion of African Americans from Congress, 1887–1929 On December 5, 1887, for the first time in almost two decades, Congress convened without an African-American Member. “All the men who stood up in awkward squads to be sworn in on Monday had white faces,” noted a correspondent for the Philadelphia Record of the Members who took the oath of office on the House Floor. “The negro is not only out of Congress, he is practically out of politics.”1 Though three black men served in the next Congress (51st, 1889–1891), the number of African Americans serving on Capitol Hill diminished significantly as the congressional focus on racial equality faded. Only five African Americans were elected to the House in the next decade: Henry Cheatham and George White of North Carolina, Thomas Miller and George Murray of South Carolina, and John M. Langston of Virginia. But despite their isolation, these men sought to represent the interests of all African Americans. Like their predecessors, they confronted violent and contested elections, difficulty procuring desirable committee assignments, and an inability to pass their legislative initiatives. Moreover, these black Members faced further impediments in the form of Thomas Rice created the character “the legalized segregation and disfranchisement, general disinterest in progressive racial Jim Crow minstrel” in 1828. The actor legislation, and the increasing power of southern conservatives in Congress. was one of the first to don blackface makeup and perform as a racially In the decade after the 1876 presidential election, the Republican-dominated stereotyped character.