Stephen Tuck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How North Carolina's Black Politicians and Press Narrated and Influenced the Tu

D. SHARPLEY 1 /133 Black Discourses in North Carolina, 1890-1902: How North Carolina’s Black Politicians and Press Narrated and Influenced the Tumultuous Era of Fusion Politics By Dannette Sharpley A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors Department of History, Duke University Under the advisement of Dr. Nancy MacLean April 13, 2018 D. SHARPLEY 2 /133 Acknowledgements I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to write an Honors Thesis in the History Department. When I returned to school after many years of separation, I was prepared for challenging work. I expected to be pushed intellectually and emotionally. I expected to struggle through all-nighters, moments of self-doubt, and even academic setbacks. I did not, however, imagine that I could feel so passionate or excited about what I learned in class. I didn’t expect to even undertake such a large project, let alone arrive at the finish line. And I didn’t imagine the sense of accomplishment at having completed something that I feel is meaningful beyond my own individual education. The process of writing this thesis has been all those things and more. I would first like to thank everyone at the History Department who supports this Honors Distinction program, because this amazing process would not be possible without your work. Thank you very much to Dr. Nancy MacLean for advising me on this project. It was in Professor MacLean’s History of Modern Social Movements class that I became obsessed with North Carolina’s role in the Populist movement of the nineteenth, thus beginning this journey. -

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

“The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell” JIM CROW AND THE EXCLUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS FROM CONGRESS, 1887–1929 On December 5, 1887, for the first time in almost two decades, Congress convened without an African-American Member. “All the men who stood up in awkward squads to be sworn in on Monday had white faces,” noted a correspondent for the Philadelphia Record of the Members who took the oath of office on the House Floor. “The negro is not only out of Congress, he is practically out of politics.”1 Though three black men served in the next Congress (51st, 1889–1891), the number of African Americans serving on Capitol Hill diminished significantly as the congressional focus on racial equality faded. Only five African Americans were elected to the House in the next decade: Henry Cheatham and George White of North Carolina, Thomas Miller and George Murray of South Carolina, and John M. Langston of Virginia. But despite their isolation, these men sought to represent the interests of all African Americans. Like their predecessors, they confronted violent and contested elections, difficulty procuring desirable committee assignments, and an inability to pass their legislative initiatives. Moreover, these black Members faced further impediments in the form of legalized segregation and disfranchisement, general disinterest in progressive racial legislation, and the increasing power of southern conservatives in Congress. John M. Langston took his seat in Congress after contesting the election results in his district. One of the first African Americans in the nation elected to public office, he was clerk of the Brownhelm (Ohio) Townshipn i 1855. -

Twin Cities Public Television, Slavery by Another Name

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Public Programs application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/public/americas-media-makers-production-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Public Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Slavery By Another Name Institution: Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. Project Director: Catherine Allan Grant Program: America’s Media Makers: Production Grants 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 426, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8269 F 202.606.8557 E [email protected] www.neh.gov SLAVERY BY ANOTHER NAME NARRATIVE A. PROGRAM DESCRIPTION Twin Cities Public Television requests a production grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) for a multi-platform initiative entitled Slavery by Another Name based upon the 2008 Pulitzer Prize-winning book written by Wall Street Journal reporter Douglas Blackmon. Slavery by Another Name recounts how in the years following the Civil War, insidious new forms of forced labor emerged in the American South, keeping hundreds of thousands of African Americans in bondage, trapping them in a brutal system that would persist until the onset of World War II. -

Slavery by Another Name History Background

Slavery by Another Name History Background By Nancy O’Brien Wagner, Bluestem Heritage Group Introduction For more than seventy-five years after the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of the Civil War, thousands of blacks were systematically forced to work against their will. While the methods of forced labor took on many forms over those eight decades — peonage, sharecropping, convict leasing, and chain gangs — the end result was a system that deprived thousands of citizens of their happiness, health, and liberty, and sometimes even their lives. Though forced labor occurred across the nation, its greatest concentration was in the South, and its victims were disproportionately black and poor. Ostensibly developed in response to penal, economic, or labor problems, forced labor was tightly bound to political, cultural, and social systems of racial oppression. Setting the Stage: The South after the Civil War After the Civil War, the South’s economy, infrastructure, politics, and society were left completely destroyed. Years of warfare had crippled the South’s economy, and the abolishment of slavery completely destroyed what was left. The South’s currency was worthless and its financial system was in ruins. For employers, workers, and merchants, this created many complex problems. With the abolishment of slavery, much of Southern planters’ wealth had disappeared. Accustomed to the unpaid labor of slaves, they were now faced with the need to pay their workers — but there was little cash available. In this environment, intricate systems of forced labor, which guaranteed cheap labor and ensured white control of that labor, flourished. For a brief period after the conclusion of fighting in the spring of 1865, Southern whites maintained control of the political system. -

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THAT OUR GOVERNMENT MAY STAND”: AFRICAN AMERICAN POLITICS IN THE POSTBELLUM SOUTH, 1865-1901 By LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Mia Bay and Ann Fabian and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “That Our Government May Stand”: African American Politics in the Postbellum South, 1865-1913 by LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO Dissertation Director: Mia Bay and Ann Fabian This dissertation provides a fresh examination of black politics in the post-Civil War South by focusing on the careers of six black congressmen after the Civil War: John Mercer Langston of Virginia, James Thomas Rapier of Alabama, Robert Smalls of South Carolina, John Roy Lynch of Mississippi, Josiah Thomas Walls of Florida, and George Henry White of North Carolina. It examines the career trajectories, rhetoric, and policy agendas of these congressmen in order to determine how effectively they represented the wants and needs of the black electorate. The dissertation argues that black congressmen effectively represented and articulated the interests of their constituents. They did so by embracing a policy agenda favoring strong civil rights protections and encompassing a broad vision of economic modernization and expanded access for education. Furthermore, black congressmen embraced their role as national leaders and as spokesmen not only for their congressional districts and states, but for all African Americans throughout the South. -

George Henry White: the American Phoenix

George Henry White: The American Phoenix "This is perhaps the Negroes' temporary farewell to the American Congress, but let me say, Phoenix-like he will rise up some day and come again. These parting words are in behalf of an outraged, heart-broken, bruised and bleeding, but God- fearing people; faithful, industrious, loyal, rising people – full of potential force." ~George Henry White Overview In this lesson students examine the life and career of North Carolina native George Henry White, the last African American Congressman before the Jim Crow Era, as well as the reasons for the decline in African American representation in Congress during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Through examination of Congressional data from the time period, viewing a documentary (optional), analyzing speech excerpts, class discussion, and more, students will gain a comprehensive understanding of the political, cultural and racial realities of the Jim Crow Era. The lesson culminates with an assignment where students are tasked with creating a reelection campaign for White. Grades 8-12 Materials • “George Henry White: American Phoenix” 15-minute documentary; available at http://www.georgehenrywhite.com/ o Teachers can also utilize online information to share with students (via lecture or having them read a handout) at https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/george-henry-white • Computers with internet access for student research (optional) • “African American Members in Congress, 1869 - 1913”, attached (p. 9-10) • “The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell: Jim Crow and the Exclusion of African Americans from Congress, 1887– 1929”, attached (p. 11-12) • “American Phoenix Viewing Guide”, attached (p. 13) • “George Henry White Quotes”, attached (p. -

Nothing Complicated About Ordinary Equality: Alice Paul and Self-Sacrifice

Nothing Complicated About Ordinary Equality: Alice Paul and Self-Sacrifice Handout A: Narrative BACKGROUND The organized reform movement for American women’s economic and legal rights, including suffrage, is commonly dated from the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. At this meeting of about 300 people, Elizabeth Cady Stanton read her Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, and 100 attendees signed the document. Stanton met Susan B. Anthony three years later and for the next half century the two women collaborated in a powerful partnership focused on numerous social reforms including the abolition of slavery, support for temperance, and pursuit of legal equality for women. In 1885, Alice Paul was born to a Quaker family in New Jersey, and as a small child she attended women’s suffrage events with her mother. She would become one of the most powerful voices for women’s rights in the new century, bringing new life to a movement that had stalled out by 1900. NARRATIVE From a young age, Paul demonstrated outstanding academic promise, and though she studied social work and served the poor at settlement houses, she disdained the typical professions open to women: nursing, teaching, and social work. She later explained, “I knew in a very short time I was never going to be a social worker, because I could see that social workers were not doing much good in the world…you couldn’t change the situation by social work.” After completing a bachelor’s degree in biology and then a master’s degree in sociology, Paul sailed to Great Britain in 1907. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO the Penitentiary at Richmond

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Penitentiary at Richmond: Slavery, State Building, and Labor in the South’s First State Prison A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Hilary Louise Coulson Committee in charge: Professor Rebecca Jo Plant, Chair Professor Stephen D. Cox Professor Mark Hanna Professor Mark Hendrickson Professor Rachel Klein 2016 Copyright Hilary Louise Coulson, 2016 All Rights Reserved The Dissertation of Hilary Louise Coulson is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii DEDICATION For my parents, Richard and Laura Coulson who always believed I could, and for my husband, Frank Fernandez, who helped me prove it. iv EPIGRAPH “You know we don’t have our prisons like yours of the North, like grand palaces with flower-yards.” –Keeper of the Virginia Penitentiary, c. 1866 v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ............................................................................................... iii Dedication ...................................................................................................... -

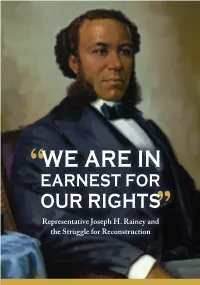

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

AMERICAN NEGRO EXHIBIT" of 1900 by Miles Everett Travis A

MIXED MESSAGES: THOMAS CALLOWAY AND THE “AMERICAN NEGRO EXHIBIT" OF 1900 by Miles Everett Travis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2004 © COPYRIGHT by Miles Everett Travis 2004 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Miles Everett Travis This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the College of Graduate Studies. Robert Rydell Approved for the Department of History Robert Rydell Approved for the College of Graduate Studies Bruce McLeod iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under the rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed by the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Miles Everett Travis April 19, 2004 iv This thesis is dedicated to Brooklynne Arcadia the love of my life, my help and my partner together before God and His creation. v The author of this thesis was born, Miles Everett Travis, son of Larry Everett and Beverly Holleman Travis, on the sixth of March 1978, in Fayetteville, North Carolina. -

When African-Americans Were Republicans in North Carolina, the Target of Suppressive Laws Was Black Republicans. Now That They

When African-Americans Were Republicans in North Carolina, The Target of Suppressive Laws Was Black Republicans. Now That They Are Democrats, The Target Is Black Democrats. The Constant Is Race. A Report for League of Women Voters v. North Carolina By J. Morgan Kousser Table of Contents Section Title Page Number I. Aims and Methods 3 II. Abstract of Findings 3 III. Credentials 6 IV. A Short History of Racial Discrimination in North Carolina Politics A. The First Disfranchisement 8 B. Election Laws and White Supremacy in the Post-Civil War South 8 C. The Legacy of White Political Supremacy Hung on Longer in North Carolina than in Other States of the “Rim South” 13 V. Democratizing North Carolina Election Law and Increasing Turnout, 1995-2009 A. What Provoked H.B. 589? The Effects of Changes in Election Laws Before 2010 17 B. The Intent and Effect of Election Laws Must Be Judged by their Context 1. The First Early Voting Bill, 1993 23 2. No-Excuse Absentee Voting, 1995-97 24 3. Early Voting Launched, 1999-2001 25 4. An Instructive Incident and Out-of-Precinct Voting, 2005 27 5. A Fair and Open Process: Same-Day Registration, 2007 30 6. Bipartisan Consensus on 16-17-Year-Old-Preregistration, 2009 33 VI. Voter ID and the Restriction of Early Voting: The Preview, 2011 A. Constraints 34 B. In the Wings 34 C. Center Stage: Voter ID 35 VII. H.B. 589 Before and After Shelby County A. Process Reveals Intention 37 B. Facts 1. The Extent of Fraud 39 2. -

Lynched for Drinking from a White Man's Well

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse this site you are agreeing to our use of cookies.× (More Information) Back to article page Back to article page Lynched for Drinking from a White Man’s Well Thomas Laqueur This April, the Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit law firm in Montgomery, Alabama, opened a new museum and a memorial in the city, with the intention, as the Montgomery Advertiser put it, of encouraging people to remember ‘the sordid history of slavery and lynching and try to reconcile the horrors of our past’. The Legacy Museum documents the history of slavery, while the National Memorial for Peace and Justice commemorates the black victims of lynching in the American South between 1877 and 1950. For almost two decades the EJI and its executive director, Bryan Stevenson, have been fighting against the racial inequities of the American criminal justice system, and their legal trench warfare has met with considerable success in the Supreme Court. This legal work continues. But in 2012 the organisation decided to devote resources to a new strategy, hoping to change the cultural narratives that sustain the injustices it had been fighting. In 2013 it published a report called Slavery in America: The Montgomery Slave Trade, followed two years later by the first of three reports under the title Lynching in America, which between them detailed eight hundred cases that had never been documented before. The United States sometimes seems to be committed to amnesia, to forgetting its great national sin of chattel slavery and the violence, repression, endless injustices and humiliations that have sustained racial hierarchies since emancipation.