Oral History Interview with Carol Eckert, 2007 June 18-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Textileartscouncil William Morrisbibliography V2

TAC Virtual Travels: The Arts and Crafts Heritage of William and May Morris, August 2020 Bibliography Compiled by Ellin Klor, Textile Arts Council Board. ([email protected]) William Morris and Morris & Co. 1. Sites A. Standen House East Grinstead, (National Trust) https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/standen-house-and-garden/features/discover-the- house-and-collections-at-standen Arts and Crafts family home with Morris & Co. interiors, set in a beautiful hillside garden. Designed by Philip Webb, taking inspiration from the local Sussex vernacular, and furnished by Morris & Co., Standen was the Beales’ country retreat from 1894. 1. Heni Talks- “William Morris: Useful Beauty in the Home” https://henitalks.com/talks/william-morris-useful-beauty/ A combination exploration of William Morris and the origins of the Arts & Crafts movement and tour of Standen House as the focus by art historian Abigail Harrison Moore. a. Bio of Dr. Harrison Moore- https://theconversation.com/profiles/abigail- harrison-moore-121445 B. Kelmscott Manor, Lechlade - Managed by the London Society of Antiquaries. https://www.sal.org.uk/kelmscott-manor/ Closed through 2020 for restoration. C. Red House, Bexleyheath - (National Trust) https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/red-house/history-at-red-house When Morris and Webb designed Red House and eschewed all unnecessary decoration, instead choosing to champion utility of design, they gave expression to what would become known as the Arts and Crafts Movement. Morris’ work as both a designer and a socialist were intrinsically linked, as the creation of the Arts and Crafts Movement attests. D. William Morris Gallery - Lloyd Park, Forest Road, Walthamstow, London, E17 https://www.wmgallery.org.uk/ From 1848 to 1856, the house was the family home of William Morris (1834-1896), the designer, craftsman, writer, conservationist and socialist. -

The Dictionary of Needlework

LIBRARY ^tsSSACHt; ^^ -^^ • J895 I ItVc^Cy*cy i/&(://^ n^ / L^^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/dictionaryofneed02caul THE DICTIONARY OF NEEDLEWORK. APPLIQUE UPON LINEN CLOTH APPLIQUE. DEDICATED TO H.R.H. PRINCESS LOUISE, MARCHIONESS OF LORNE. THE Dic;tioi];?^y of I^eedle!ho^^, ENOYCLOPiEDIA OE ARTISTIC, PLAIN, AND EANCY NEEDLEWORK, DEALING FULLY "WITH THE DETAILS OF ALL THE STITCHES EMPLOYED, THE METHOD OF "WORKING, THE MATERIALS USED, THE MEANING OF TECHNICAL TERMS, AND, "WHERE NECESSARY. TRACING THE ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF THE VARIOUS "WORKS DESCRIBED. ILLUSTRATED WITH UPWARDS OF 1200 WOOD ENG-RAYINGS, AND COLOURED PLATES. PLAIN SE"WING, TEXTILES, DRESSMAKING, APPLIANCES, AND TERMS, By S. E. a. CAULEEILD, Author of "Skic iVtjrs»i(7 at Home," "Desmond," "Avencle," and Papers on Needlework in "The Queen," "Girl's Own Paper "Cassell's Domestic Dictionary," iDc. CHURCH EMBROIDERY, LACE, AND ORNAMENTAL NEEDLEWORK, By blanche C. SAWARD, Author of "'•Church Festiva^l Decorations," and Papers on Fancy and Art Work in ''The Bazaar," "Artistic Aimcsements," "Girl's Own Paper," ii:c. Division II.— Cre to Emb. SECOND EDITION. LONDON: A. W. COWAN, 30 AND 31, NEW BRIDGE STREET, LUDGATE CIRCUS. 'A \^'0^ ^' ... ,^\ STRAND LONDON : PRINTED BY A. BRADLEY, 170, ^./^- c^9V^ A^A^'f THE DICTIONARY OF NEEDLEWORK. 97 Knots for the centre of flowers, as tliey add to their and taste of that period. The great merit of the work beauty. When the centre of a flower is as large as that and the reason of its revival lies in the capability it has of seen in a sunflower, either work the whole with French expressing the thought of the worker, and its power of Knots, or lay down a piece of velvet of the right shade and breaking through the trammels of that mechanical copy- work sparingly over it French Knots or lines of Crewel ing and counting which lowers most embroidery to mere Stitch. -

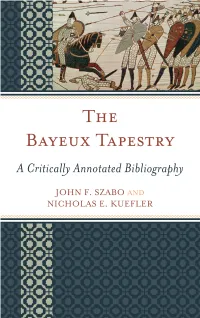

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

MAY MORRIS. MUJER ARTESANA: Su Papel En El Movimiento Arts and Crafts

MAY MORRIS. MUJER ARTESANA: su papel en el movimiento Arts and Crafts TFG GRADO EN HISTORIA DEL ARTE UNIVERSIDAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DE VALLADOLID TUTOR: VÍCTOR LÓPEZ LORENTE Diciembre 2019 Eulalia Mateos Guzmán May Morris. Mujer Artesana: su papel en el movimiento Arts and Crafts 2 May Morris. Mujer Artesana: su papel en el movimiento Arts and Crafts ÍNDICE Definición y objetivos del TFG ( p. 5). Elaboración del estado de la cuestión sobre el tema expuesto ( p. 6-7). Exposición y justificación de la metodología o las metodologías empleadas y el uso de las TICS ( p. 8). IV. EstructuraciAn y ordenaciAn de los diferentes apartados del trabajo (p. 9). V. Desarrollo del trabajo: (p. 10-44). V.1. Contexto histArico-social del Movimiento Arts and Crafts (p. 10-11). V.2. El papel de la mujer en el Movimiento Arts and Crafts en Inglaterra ( p.12-14). V.3. May Morris: V. 3. 1. El padre de May Morris: William Morris (p. 15-20). V. 3. 2. May Morris: Vida (p. 20-23). V. 3. 3. May Morris: Artesana: V. 3. 3. a. IntroducciAn (p. 24). V. 3. 3. b. Bordado (p. 25-28). T>cnica (p. 29-30). V. 3. 3. c. Indumentaria (p. 30-34). 3 May Morris. Mujer Artesana: su papel en el movimiento Arts and Crafts V. 3. 3. d. Papel tapiz (p. 34-36). V. 3. 3. e. Joyer?a (p. 36-41). V. 3. 3. f. EncuadernaciAn y escritos (p. 41-44). VI. Conclusiones (p. 45-46). VII. Bibliograf?a (p. 47-50). -

Albuquerque Morning Journal, 12-13-1914 Journal Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 12-13-1914 Albuquerque Morning Journal, 12-13-1914 Journal Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_mj_news Recommended Citation Journal Publishing Company. "Albuquerque Morning Journal, 12-13-1914." (1914). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ abq_mj_news/1143 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALBUQUEMQUE '.HORNING JTODTRN THIRTY-SIXT- H YEAR 1914,"" Dully by Carrier or Mail 71. EIGHTEEN ALBUQUERQUE, MEXICO, SUNDAY, DECEMBER 13, SECTION ONE-P-agcs 1 to 8. l.. XXX XIV. N. PAGESIN THREE SECTIONS. NEW J Month. Mnitl CoplM. Tiilte.1 ! StaW to vt.te ahull not be d Summary of War iPUDICTMAOTDIIPr SWEDES DISSATISFIED PROHIBIT! TD or abridged on account of sex. EE RMAN REPOR T DEVELOPMENTS During the day the council of one News of Yesterday UllllldllVlflJ IIIUUL WITH GERMAN ANSWER hundred, orptinlKed for united tem- perance educational work last year at MORNIKd JUUNNAI. BPirlAl l.f AtO WIKI) Columbus, O., While .flghl'iic !., liiit on both nr n held Its first anmiai '.'tin Kholiii I via London. Dec. 12. ML miIff n II UiJLULnnrnnirI BE VOTED OM BY meeting. Tho name In the i n't nun ihi' w Kt Hlollg (He ASKED BY II of the organiza- SAYS RUSSIAN POPE 11:34 p. -

Talliaferro Classic Needleart Has Generously Contributed Two Motifs of Her Own Design for You to Interpret Into Stitch

rancisco Scho n F ol o Sa f Stitch at Home Challenge Deadline: April 15, 2017 What is the “Stitch at Home Challenge”? We have created the “Stitch at Home Challenge” as a way to encourage and inspire people to stitch. This is not a competition but a challenge. For each challenge we will provide you with an inspiration and you may use any needlework technique or combination of techniques in order to make a piece of textile art. We will offer a new Challenge and Inspiration quarterly. Who can enter? Anyone! We know that many of you live far away. If you can’t come and visit us here in San Francisco, this is a great opportunity for you to join our stitching community. If you live close by, you may have the chance to come in and see your work on display at our school during one of our exhibits! What do I do with my finished piece? Your finished piece of art belongs to you but for each challenge there will be a deadline for you to submit either a photograph of your piece or the actual piece itself for display in an exhibit. The Challenge Exhibit will be up for a month at SNAD and it is a great opportunity to showcase your work. With your permission, we will also display your work in an online gallery on our website. THIS CHALLENGE’S INSPIRATION: For this challenge, Anna Garris Goiser of Talliaferro Classic Needleart has generously contributed two motifs of her own design for you to interpret into stitch. -

The Inspired Needle: Embroidery Past & Present a VIRTUAL WINTERTHUR CONFERENCE OCTOBER 2–3, 2020

16613NeedleworkBrochureFA.qxp_needlework2020 7/29/20 1:20 PM Page 1 The Inspired Needle: Embroidery Past & Present A VIRTUAL WINTERTHUR CONFERENCE OCTOBER 2–3, 2020 Embroidery is both a long-standing tradition and a contemporary craft. It reflects the intellectual endeavors, enlivens the political debates, and empowers the entrepreneurial pursuits of those who dare to pick up a needle. Inspiration abounds during this two-day celebration of needlework—and needleworkers—presented by Winterthur staff, visiting scholars, designers, and artists. Registration opens August 1, 2020. Join us! REGISTER NOW Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library 16613NeedleworkBrochureFA.qxp_needlework2020 7/29/20 1:20 PM Page 2 THE INSPIRED NEEDLE: EMBROIDERY PAST AND PRESENT LECTURES ON DEMAND Watch as many times as you wish during the month of October. Each lecture lasts approximately 45 minutes. Downloading or recording of presentations is prohibited. Patterns and Pieces: Whitework Samplers Mary Linwood and the Business of Embroidery of the 17th Century Heidi Strobel, Professor of Art History, University of Tricia Wilson Nguyen, Owner, Thistle Threads, Arlington, MA Evansville, IN By the end of the 17th century, patterns for several forms of In 1809, embroiderer Mary Linwood (1755–1845) opened a needlework had been published and distributed for more than a gallery in London’s Leicester Square, a neighborhood known hundred years. These early pattern books were kept and used by then and now for its popular entertainment. The first gallery to multiple generations as well as reproduced in multiple editions be run by a woman in London, it featured her full-size and extensively plagiarized. Close study of the patterns and needlework copies of popular paintings after beloved British samplers of the last half of the 17th century can reveal many artists Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, and George answers to the working of popular cut whitework techniques. -

A History of Embroidery

Textiles A history and price guide to British embroidery from 1500-1900s by Zita Thornton Early 19thC silkwork/embroi- dered picture, young lady with ntil the Reformation most embroidery was ecclesiastical in nature. child, 8 x 6.25in, & companion, UHowever afterwards, embroidery moved into the home and became 17thC embroidery, ‘The lady attending a tomb, marked an every day part of almost every woman and girl’s life. Girls were taught Judgement of Paris’. Tring ‘Werter’, 7.5 x 5.75in, gilt Market Auctions, Herts. Jan slips/frames. Diamond Mills by their mothers or by professional tutors, if they were wealthy. 02. HP: £3,800. ABP: £4,469. & Co, Felixstowe. Oct 06. Embroidery was a practical, creative pastime which provided compan- HP: £500. ABP: £588. ionship and raised their status. The familiar sampler provided a method for girls as young as eight to practise their stitches whilst learning their alphabet, and the texts and motifs chosen formed part of their education. Turning a seventeenth century sampler over allows us to fully appreciate the skill involved as British samplers at this time were usually reversible. 18thC embroidered frieze of Embroidery was used to decorate all kinds of flat domestic textiles, including obelisks, flowers, fruit over sheets, coverlets, table cloths, and cushions. A surge in house building in the swags/cartouches, Hogarth seventeenth century provided more scope for embroidered decorative 19thC sailor’s woolwork ship frame, 14.5 x 50cm. Sworders, portrait, 34 gun ‘Ship of the Stansted Mountfitchet. Nov furnishings to provide comfort and warmth and as a display of the family’s Line’, furled sails, decked in 05. -

Traditional Hand Embroidery and Simple Hand-Woven Structures for Garment Manufacturing Used in Small Scale Industry

ISSN: 2277-9655 [Kaur * et al., 7(6): June, 2018] Impact Factor: 5.164 IC™ Value: 3.00 CODEN: IJESS7 IJESRT INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGINEERING SCIENCES & RESEARCH TECHNOLOGY TRADITIONAL HAND EMBROIDERY AND SIMPLE HAND-WOVEN STRUCTURES FOR GARMENT MANUFACTURING USED IN SMALL SCALE INDUSTRY Rajinder Kaur*1 & Jashanjeet Kaur2 *1Dev Samaj College for Women, (Ferozpur- Punjab) India, researches 2DBFGOI, (Moga- Punjab) India DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1297392 ABSTRACT This study explores a field of textile craft, which incorporates the techniques of traditional hand embroidery design and a simple hand woven structure into construction processes of garment production to enhance the fortunes of the local fashion industry. The project was designed to have traditional and cultural significance, so as to provide a new dimension to local garment decorating processes. The results of the study revealed a wide possibility of creating and fashioning various simple hand woven structures of traditional significance into the production of garments. This provides innovative ways of actualizing new creative ideas for the progress of the local industry. The experiment revealed that with careful blending of yarns of various types, colos and sizes, very attractive and significant results can be achieved making it appropriate for use in garment decoration. The basic challenges encountered involved the variations in yarn sizes used, the long floats associated with some weave and embroidery styles and the limitations associated with the weave frame used for the project. Keywords: Hand Embroidery, Weaving, Garments. I. INTRODUCTION Embroidery was an important art in the Medieval Islamic world. The 17th-century Turkish traveler Evliya Celebi called it the "craft of the two hands". -

Download (405Kb)

Dickinson, Rachel and Rousillon-Constanty, Laurence (2018) Converging Lines: Needlework in English Literature and Visual Arts. E-rea : Revue Électronique d’Études sur le Monde Anglophone (E-rea Electronic Review of Studies on the English-speaking World), 16 (1). ISSN 1638-1718 Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/621892/ Version: Accepted Version Publisher: Laboratoire d’Etudes et de Recherches sur le Monde Anglo- phone (LERMA) Usage rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- tive Works 4.0 Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk Converging Lines: Needlework in English Literature and Visual Arts Laurence Roussillon-Constanty Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour, France [email protected] Rachel Dickinson Manchester Metropolitan University, United Kingdom [email protected] orcid.org/0000-0002-9383-2169 About the authors Laurence Roussillon-Constanty is Full Professor in English Literature, Aesthetics and Epistemology at the Université de Pau. Her main interest is text and image relations and pluridisciplinary projects. She has published several articles on Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Ruskin. She is President of the SFEVE (Société Française des Etudes Victoriennes et Edouardiennes) and a Companion of Ruskin’s Guild of St George. Rachel Dickinson is Principal Lecturer in Interdisciplinary Studies (English Literature) at Manchester Metropolitan University. She curated an exhibition on Ruskin and textiles at the Ruskin Library, Lancaster University and has published on Ruskin. She is Director of Education for Ruskin’s Guild of St George. A testament to a woman’s patience, the cross-stitch canvas illustrating this special issue of E- Rea is drawn from Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s 1868 oil painting, Il Ramoscello (Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum). -

Te Papa Annual Report 2010-2011

G.12 Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Te P ūrongo ā Tau Annual Report 2010/11 In accordance with section 150 of the Crown Entities Act 2004, this annual report of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa for 2010/11 is presented to the House of Representatives. Ng ā Ihirangi – Contents Part 1: Ng ā Tau āki Tirohanga Wh ānui – Overview Statements From the Chairman 3 From the Chief Executive and Kaihaut ū 5 Performance at a glance 7 Part 2: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Accountability and legislation 11 Vision, outcomes, outputs, and performance measures 12 Governance and management 14 Capability – people, process, and technology 17 Part 3: Te Tau āki o ng ā Paearu Ratonga me te P ūtea Statement of Service Performance and Financial Statements Statement of Service Performance 23 Financial Statements 31 Āpitihanga – Appendices Loans 65 Workshops and expert knowledge exchanges 69 Acquisitions 72 Publications and conference presentations 82 Ō m ātou hoa – Our Partners 89 2 Part 1: Ng ā Tau āki Tirohanga Wh ānui – Overview Chairman’s statement Ka mahuta ake te whakaaro ki ērā o ng ā M āreikura, ng ā r ātā whakaruruhau o runga i o t ātau marae maha, ng ā parekura, ng ā Ikahuirua o te w ā, r ātau i hakiri ai o t ātau taringa, i noho ai te ng ākau mamae, te roimata hei ārai atu i te āhuatanga m ō te hunga ka huri atu ki tua o te whar āu. Kia hoki mai ki a t ātau ng ā manu k ōrihi hei tuku i te ātahu e huri mai ai te minenga ki te tautoko i ng ā āhuatanga p āpai o te ao. -

Dalai Lama §Ays in China Production W

FRIDAY, APRIL 17, 196» MO»t^rBKrtT.Fdtm iHattrli^Btrr lEtrirning Hrralb Average Daily Net Press Run The Weather For the Week Ending Fnreeaat of U. S. Weather B «m M WRA Junions ndll meat Monday, . MiM Judith A. BaniM. 54 Alton April n, 1959 April 20, at 7 p.m. at tho home of 8t„ A frsahman at Beekay vTuntor Clniidy, milder, oreoaloHiU aheir* A bout Town Mrs. Irene La Palme. l U Walker CoUags, Woreastar, Maas., has St. A diacttasio of future plana hsan nalhsd a mt^ifbar of tha 12,910 nr* developliig tonight. S n i^ y H it maiTiag* of M in Jo-Ann will take placo and refreahmenU daan’a list for tha third quartar. Now In Progress-Hale’s Great Hale's Domestic and Member of the Audit cloudy, ohatice of showers, little DcMbM of Kut Kutford uid and a social time for the children Bureau of dreulation change In temperature. Wiiw Shim of ManchuCor will will follow. Robart O. pfsostad, S3 Comstock 'Hlanche»f^r'~—A CMy of Village ('.harm tak* placo tomorrow momlna at Rd., will ftfend ths csAdldates’ Fabric Department Brings 11 o'clodt in St. Chrirtopner'a The American Lefion Auxiliary day oparr housa at Lahigh Univer- APRIL ^ Chxirch, tihat Hartford. will hold a special meeting Mon aity, Bathleham, Pa., tomorrow. VOL. LXXVIII, NO. 169 (FODHTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER. CONN., .SAtl RDAY, APRII, 18. 19.',9 (Classlllcd .4rt,ertlsln| on l^agn 12) PRICE FIVE CENT'S day n't 8 p.m. at the Legion Homa to consider revision of the by Dr.