Art-Needlework for Decorative Embroidery;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Textileartscouncil William Morrisbibliography V2

TAC Virtual Travels: The Arts and Crafts Heritage of William and May Morris, August 2020 Bibliography Compiled by Ellin Klor, Textile Arts Council Board. ([email protected]) William Morris and Morris & Co. 1. Sites A. Standen House East Grinstead, (National Trust) https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/standen-house-and-garden/features/discover-the- house-and-collections-at-standen Arts and Crafts family home with Morris & Co. interiors, set in a beautiful hillside garden. Designed by Philip Webb, taking inspiration from the local Sussex vernacular, and furnished by Morris & Co., Standen was the Beales’ country retreat from 1894. 1. Heni Talks- “William Morris: Useful Beauty in the Home” https://henitalks.com/talks/william-morris-useful-beauty/ A combination exploration of William Morris and the origins of the Arts & Crafts movement and tour of Standen House as the focus by art historian Abigail Harrison Moore. a. Bio of Dr. Harrison Moore- https://theconversation.com/profiles/abigail- harrison-moore-121445 B. Kelmscott Manor, Lechlade - Managed by the London Society of Antiquaries. https://www.sal.org.uk/kelmscott-manor/ Closed through 2020 for restoration. C. Red House, Bexleyheath - (National Trust) https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/red-house/history-at-red-house When Morris and Webb designed Red House and eschewed all unnecessary decoration, instead choosing to champion utility of design, they gave expression to what would become known as the Arts and Crafts Movement. Morris’ work as both a designer and a socialist were intrinsically linked, as the creation of the Arts and Crafts Movement attests. D. William Morris Gallery - Lloyd Park, Forest Road, Walthamstow, London, E17 https://www.wmgallery.org.uk/ From 1848 to 1856, the house was the family home of William Morris (1834-1896), the designer, craftsman, writer, conservationist and socialist. -

The Dictionary of Needlework

LIBRARY ^tsSSACHt; ^^ -^^ • J895 I ItVc^Cy*cy i/&(://^ n^ / L^^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/dictionaryofneed02caul THE DICTIONARY OF NEEDLEWORK. APPLIQUE UPON LINEN CLOTH APPLIQUE. DEDICATED TO H.R.H. PRINCESS LOUISE, MARCHIONESS OF LORNE. THE Dic;tioi];?^y of I^eedle!ho^^, ENOYCLOPiEDIA OE ARTISTIC, PLAIN, AND EANCY NEEDLEWORK, DEALING FULLY "WITH THE DETAILS OF ALL THE STITCHES EMPLOYED, THE METHOD OF "WORKING, THE MATERIALS USED, THE MEANING OF TECHNICAL TERMS, AND, "WHERE NECESSARY. TRACING THE ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF THE VARIOUS "WORKS DESCRIBED. ILLUSTRATED WITH UPWARDS OF 1200 WOOD ENG-RAYINGS, AND COLOURED PLATES. PLAIN SE"WING, TEXTILES, DRESSMAKING, APPLIANCES, AND TERMS, By S. E. a. CAULEEILD, Author of "Skic iVtjrs»i(7 at Home," "Desmond," "Avencle," and Papers on Needlework in "The Queen," "Girl's Own Paper "Cassell's Domestic Dictionary," iDc. CHURCH EMBROIDERY, LACE, AND ORNAMENTAL NEEDLEWORK, By blanche C. SAWARD, Author of "'•Church Festiva^l Decorations," and Papers on Fancy and Art Work in ''The Bazaar," "Artistic Aimcsements," "Girl's Own Paper," ii:c. Division II.— Cre to Emb. SECOND EDITION. LONDON: A. W. COWAN, 30 AND 31, NEW BRIDGE STREET, LUDGATE CIRCUS. 'A \^'0^ ^' ... ,^\ STRAND LONDON : PRINTED BY A. BRADLEY, 170, ^./^- c^9V^ A^A^'f THE DICTIONARY OF NEEDLEWORK. 97 Knots for the centre of flowers, as tliey add to their and taste of that period. The great merit of the work beauty. When the centre of a flower is as large as that and the reason of its revival lies in the capability it has of seen in a sunflower, either work the whole with French expressing the thought of the worker, and its power of Knots, or lay down a piece of velvet of the right shade and breaking through the trammels of that mechanical copy- work sparingly over it French Knots or lines of Crewel ing and counting which lowers most embroidery to mere Stitch. -

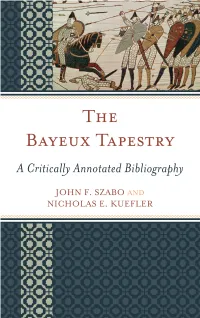

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

THE SLOW HANDS LAB the Slow Hands’ Lab

THE SLOW HANDS LAB The Slow Hands’ Lab A Thesis Project by Jiayi Dong Class of 2019 MFA, Design for Social Innovation School of Visual Arts Thesis Advisor Archie Lee Coates IV TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION 3 DESIGN PROCESS 9 INTERVENTION 31 LEARNINGS 45 LOOKING FORWARD 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 49 INTRODUCTION Suzhou embroidery (Su embroidery for short) was originated in Suzhou, China and later on spread to the neighboring areas such as Nantong and Wuxi in Jiangsu province. These areas, locat- THE HISTORY ed in the lower reach of Youngest River, have been famous for their high quality silk produc- OF SU EMBROIDERY ART tions for centuries. The fertile soil, mild tempera- ture, and booming production of silk fabric and thread naturally nourished the burgeoning and flourishing of Suzhou embroidery. According to "Shuo Yuan", written by Liu Xiang during the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC - 24 AD), the country of Wu (current Suzhou area) has started to use embroidery to decorate garments over 2,000 years ago. As described in the book of "Secret Treasures of Qing," the Suzhou embroi- ders in Song Dynasty (960-1279) used "needles that could be as thin as the hair. During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), Suzhou has become a thriving center for silk industries and handicrafts. Artists in Wu area, represented by Tang Yin (Bohu) and Shen Zhou, helped the further development of Suzhou embroidery. Embroiders reproduced their paintings using needles. These works were so vivid and elegant as to be called "paintings by needle" or "unmatch- able even by the nature." Since then, Suzhou embroidery evolved a style of its own in needle- work, color plan and pattern. -

MAY MORRIS. MUJER ARTESANA: Su Papel En El Movimiento Arts and Crafts

MAY MORRIS. MUJER ARTESANA: su papel en el movimiento Arts and Crafts TFG GRADO EN HISTORIA DEL ARTE UNIVERSIDAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DE VALLADOLID TUTOR: VÍCTOR LÓPEZ LORENTE Diciembre 2019 Eulalia Mateos Guzmán May Morris. Mujer Artesana: su papel en el movimiento Arts and Crafts 2 May Morris. Mujer Artesana: su papel en el movimiento Arts and Crafts ÍNDICE Definición y objetivos del TFG ( p. 5). Elaboración del estado de la cuestión sobre el tema expuesto ( p. 6-7). Exposición y justificación de la metodología o las metodologías empleadas y el uso de las TICS ( p. 8). IV. EstructuraciAn y ordenaciAn de los diferentes apartados del trabajo (p. 9). V. Desarrollo del trabajo: (p. 10-44). V.1. Contexto histArico-social del Movimiento Arts and Crafts (p. 10-11). V.2. El papel de la mujer en el Movimiento Arts and Crafts en Inglaterra ( p.12-14). V.3. May Morris: V. 3. 1. El padre de May Morris: William Morris (p. 15-20). V. 3. 2. May Morris: Vida (p. 20-23). V. 3. 3. May Morris: Artesana: V. 3. 3. a. IntroducciAn (p. 24). V. 3. 3. b. Bordado (p. 25-28). T>cnica (p. 29-30). V. 3. 3. c. Indumentaria (p. 30-34). 3 May Morris. Mujer Artesana: su papel en el movimiento Arts and Crafts V. 3. 3. d. Papel tapiz (p. 34-36). V. 3. 3. e. Joyer?a (p. 36-41). V. 3. 3. f. EncuadernaciAn y escritos (p. 41-44). VI. Conclusiones (p. 45-46). VII. Bibliograf?a (p. 47-50). -

Medieval Clothing and Textiles

Medieval Clothing & Textiles 2 Robin Netherton Gale R. Owen-Crocker Medieval Clothing and Textiles Volume 2 Medieval Clothing and Textiles ISSN 1744–5787 General Editors Robin Netherton St. Louis, Missouri, USA Gale R. Owen-Crocker University of Manchester, England Editorial Board Miranda Howard Haddock Western Michigan University, USA John Hines Cardiff University, Wales Kay Lacey Swindon, England John H. Munro University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada M. A. Nordtorp-Madson University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, USA Frances Pritchard Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, England Monica L. Wright Middle Tennessee State University, USA Medieval Clothing and Textiles Volume 2 edited by ROBIN NETHERTON GALE R. OWEN-CROCKER THE BOYDELL PRESS © Contributors 2006 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2006 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 1 84383 203 8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA website: www.boydellandbrewer.com A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library This publication is printed on acid-free paper Typeset by Frances Hackeson Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs Printed in Great Britain by Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Contents Illustrations page vii Tables ix Contributors xi Preface xiii 1 Dress and Accessories in the Early Irish Tale “The Wooing Of 1 Becfhola” Niamh Whitfield 2 The Embroidered Word: Text in the Bayeux Tapestry 35 Gale R. -

Albuquerque Morning Journal, 12-13-1914 Journal Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 12-13-1914 Albuquerque Morning Journal, 12-13-1914 Journal Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_mj_news Recommended Citation Journal Publishing Company. "Albuquerque Morning Journal, 12-13-1914." (1914). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ abq_mj_news/1143 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALBUQUEMQUE '.HORNING JTODTRN THIRTY-SIXT- H YEAR 1914,"" Dully by Carrier or Mail 71. EIGHTEEN ALBUQUERQUE, MEXICO, SUNDAY, DECEMBER 13, SECTION ONE-P-agcs 1 to 8. l.. XXX XIV. N. PAGESIN THREE SECTIONS. NEW J Month. Mnitl CoplM. Tiilte.1 ! StaW to vt.te ahull not be d Summary of War iPUDICTMAOTDIIPr SWEDES DISSATISFIED PROHIBIT! TD or abridged on account of sex. EE RMAN REPOR T DEVELOPMENTS During the day the council of one News of Yesterday UllllldllVlflJ IIIUUL WITH GERMAN ANSWER hundred, orptinlKed for united tem- perance educational work last year at MORNIKd JUUNNAI. BPirlAl l.f AtO WIKI) Columbus, O., While .flghl'iic !., liiit on both nr n held Its first anmiai '.'tin Kholiii I via London. Dec. 12. ML miIff n II UiJLULnnrnnirI BE VOTED OM BY meeting. Tho name In the i n't nun ihi' w Kt Hlollg (He ASKED BY II of the organiza- SAYS RUSSIAN POPE 11:34 p. -

Talliaferro Classic Needleart Has Generously Contributed Two Motifs of Her Own Design for You to Interpret Into Stitch

rancisco Scho n F ol o Sa f Stitch at Home Challenge Deadline: April 15, 2017 What is the “Stitch at Home Challenge”? We have created the “Stitch at Home Challenge” as a way to encourage and inspire people to stitch. This is not a competition but a challenge. For each challenge we will provide you with an inspiration and you may use any needlework technique or combination of techniques in order to make a piece of textile art. We will offer a new Challenge and Inspiration quarterly. Who can enter? Anyone! We know that many of you live far away. If you can’t come and visit us here in San Francisco, this is a great opportunity for you to join our stitching community. If you live close by, you may have the chance to come in and see your work on display at our school during one of our exhibits! What do I do with my finished piece? Your finished piece of art belongs to you but for each challenge there will be a deadline for you to submit either a photograph of your piece or the actual piece itself for display in an exhibit. The Challenge Exhibit will be up for a month at SNAD and it is a great opportunity to showcase your work. With your permission, we will also display your work in an online gallery on our website. THIS CHALLENGE’S INSPIRATION: For this challenge, Anna Garris Goiser of Talliaferro Classic Needleart has generously contributed two motifs of her own design for you to interpret into stitch. -

Canadian Embroiderers Guild Guelph LIBRARY August 25, 2016

Canadian Embroiderers Guild Guelph LIBRARY August 25, 2016 GREEN text indicates an item in one of the Small Books boxes ORANGE text indicates a missing book PURPLE text indicates an oversize book BANNERS and CHURCH EMBROIDERY Aber, Ita THE ART OF JUDIAC NEEDLEWORK Scribners 1979 Banbury & Dewer How to design and make CHURCH KNEELERS ASN Publishing 1987 Beese, Pat EMBROIDERY FOR THE CHURCH Branford 1975 Blair, M & Ryan, Cathleen BANNERS AND FLAGS Harcourt, Brace 1977 Bradfield,Helen; Prigle,Joan & Ridout THE ART OF THE SPIRIT 1992 CEG CHURCH NEEDLEWORK EmbroiderersGuild1975T Christ Church Cathedral IN HIS HOUSE - THE STORY OF THE NEEDLEPOINT Christ Church Cathedral KNEELERS Dean, Beryl EMBROIDERY IN RELIGION AND CEREMONIAL Batsford 1981 Exeter Cathedra THE EXETER RONDELS Penwell Print 1989 Hall, Dorothea CHURCH EMBROIDERY Lyric Books Ltd 1983 Ingram, Elizabeth ed. THREAD OF GOLD (York Minster) Pitken 1987 King, Bucky & Martin, Jude ECCLESSIASTICAL CRAFTS VanNostrand 1978 Liddell, Jill THE PATCHWORK PILGRIMAGE VikingStudioBooks1993 Lugg, Vicky & Willcocks, John HERALDRY FOR EMBROIDERERS Batsford 1990 McNeil, Lucy & Johnson, Margaret CHURCH NEEDLEWORK, SANCTUARY LINENS Roth, Ann NEEDLEPOINT DESIGNS FROM THE MOSAICS OF Scribners 1975 RAVENNA Wolfe, Betty THE BANNER BOOK Moorhouse-Barlow 1974 CANVASWORK and BARGELLO Alford, Jane BEGINNERS GUIDE TO BERLINWORK Awege, Gayna KELIM CANVASWORK Search 1988 T Baker, Muriel: Eyre, Barbara: Wall, Margaret & NEEDLEPOINT: DESIGN YOUR OWN Scribners 1974 Westerfield, Charlotte Bucilla CANVAS EMBROIDERY STITCHES Bucilla T. Fasset, Kaffe GLORIOUS NEEDLEPOINT Century 1987 Feisner,Edith NEEDLEPOINT AND BEYOND Scribners 1980 Felcher, Cecelia THE NEEDLEPOINT WORK BOOK OF TRADITIONAL Prentice-Hall 1979 DESIGNS Field, Peggy & Linsley, June CANVAS EMBROIDERY Midhurst,London 1990 Fischer,P.& Lasker,A. -

The Inspired Needle: Embroidery Past & Present a VIRTUAL WINTERTHUR CONFERENCE OCTOBER 2–3, 2020

16613NeedleworkBrochureFA.qxp_needlework2020 7/29/20 1:20 PM Page 1 The Inspired Needle: Embroidery Past & Present A VIRTUAL WINTERTHUR CONFERENCE OCTOBER 2–3, 2020 Embroidery is both a long-standing tradition and a contemporary craft. It reflects the intellectual endeavors, enlivens the political debates, and empowers the entrepreneurial pursuits of those who dare to pick up a needle. Inspiration abounds during this two-day celebration of needlework—and needleworkers—presented by Winterthur staff, visiting scholars, designers, and artists. Registration opens August 1, 2020. Join us! REGISTER NOW Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library 16613NeedleworkBrochureFA.qxp_needlework2020 7/29/20 1:20 PM Page 2 THE INSPIRED NEEDLE: EMBROIDERY PAST AND PRESENT LECTURES ON DEMAND Watch as many times as you wish during the month of October. Each lecture lasts approximately 45 minutes. Downloading or recording of presentations is prohibited. Patterns and Pieces: Whitework Samplers Mary Linwood and the Business of Embroidery of the 17th Century Heidi Strobel, Professor of Art History, University of Tricia Wilson Nguyen, Owner, Thistle Threads, Arlington, MA Evansville, IN By the end of the 17th century, patterns for several forms of In 1809, embroiderer Mary Linwood (1755–1845) opened a needlework had been published and distributed for more than a gallery in London’s Leicester Square, a neighborhood known hundred years. These early pattern books were kept and used by then and now for its popular entertainment. The first gallery to multiple generations as well as reproduced in multiple editions be run by a woman in London, it featured her full-size and extensively plagiarized. Close study of the patterns and needlework copies of popular paintings after beloved British samplers of the last half of the 17th century can reveal many artists Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, and George answers to the working of popular cut whitework techniques. -

Royal School of Needlework Annual Review 2016-2017

Royal School of Needlework Annual Review 2016-2017 Mission The mission of the Royal School of Needlework (RSN) is to teach, practise and promote the art and techniques of hand embroidery. Vision The vision of the RSN is to be known and recognised as the international centre of excellence for hand embroidery offering a common approach everywhere we teach are open to all levels, from beginners to advanced, and students of all ages; to be both the custodian of the history of hand embroidery techniques and active advocates of new developments in hand embroidery. A Laudian altar frontal designed and created by the RSN for the Chapel Royal, Hampton Court Pal- ace and used for the first time when Her Majesty The Queen attended the com- memorative service for the Companions of Honour. Public Benefit men which attracted over 20,000 visitors (below left) and our exhibition celebrating our 30th anniversary of being During the year the RSN met its public benefit obligations based at Hampton Court Palace which attracted 5,000 in a variety of ways. We demonstrated hand stitching for people from around the world (below right). Burberry and The New Craftsmen (front cover) at Mak- End-of-year shows were held for all the main courses: ers’ House a pop up event which highlighted the inspira- Future Tutors, Certificate, Diploma and Degree each of tion and craftsmanship behind the AW 2017 Burberry which was open to all. The RSN was selected by English collection attracting thousands of visitors. Heritage to be one of its London icons and we asked The RSN showed or loaned work from our Collection to a now qualified Future Tutor Kate Barlow to be photo- range of events including an exhibition of cross stitch graphed for the exhibition (centre) which was held at curated by Mr X Stitch. -

Discovery Chest Artifact Description Cards Child’S Rattle Who Would Have Used This? • Children

China Discovery Chest Artifact Description Cards Child’s Rattle Who would have used this? • Children. What is this? • A popular children’s toy. Two small balls attached to the sides beat the hollow drum when it is spun. Its surface is sometimes painted. It is often found at festivals such as the Lunar New Year. What is its significance? • The Chinese hand drum, also called a rattle drum, originated in ancient China around 475-221 BC during the Song Dynasty (960-1276). China 1A, GAMES Tiger Mask Who would have used this? • Children. What is this? • A traditional baby gift that is usually silk with hand stitching and embroidered appliques. The tiger is believed to protect the child from bad spirits and bring good luck. What is its significance? • The tiger hat can be traced as far back as the Qing dynasty. China 2A, GAMES Tangrams Who would have used this? • Children. What is this? • The tangram is a very old puzzle originating in China and is sometimes called the Wisdom Puzzle. The set consists of seven pieces: five triangles, one square, and one rhomboid. When fitted together, these shapes make a design or picture. What is its significance? • The story goes that about four thousand years ago in China, a man named Tan went to show the emperor a fine ceramic tile, but on his way he fell and his tile broke into 7 pieces. Tan spent the rest of his life trying to put the pieces back together, but was unsuccessful. However, he made many different shapes and pictures.