A Preliminary Sketch of Wallingford's History 1855

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ohio Historical Newspapers by Region

OHIO HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSPAPER INDEX UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES, WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY Alphabetical by Region Arcanum Arcanum Time (weekly) May 11, 1899 - Jan 2, 1902 Aug. 27, 1903 - Dec. 20, 1905 April 26, 1906 – Dec. 22, 1910 May 2, 1912 – Jan 19, 1950 April 20, 1950 – Feb 9, 1961 Oct. 18 – 25, 1962 Darke Times Feb 16, 1961 – Dec 27, 1962 June 6, 1968 – Jan 23, 1969 July 3, 1969 –June 26, 1970 Early Bird (weekly) Nov 1, 1971- May 3,1977 Nov 16, 1981- Dec 27,1993 Early Bird Shopper June 2, 1969 – Oct 25,1971 Bath Township BZA Minutes 1961-1973 Trustees Minutes v.1 – 13 1849 – 1869 1951 – 1958 Beavercreek Beavercreek Daily News 1960-1962 1963 -1964 Jan 1975 – June 1978 March 1979 – Nov 30, 1979 Beavercreek News Jan 1965 – Dec 1974 Bellbrook Bellbrook Moon Sept 14, 1892 – June 23, 1897 Bellbrook-Sugarcreek Post May 19, 1965 – April 7, 1971 Bellefontaine Bellefontaine Gazette Feb 25, 1831 – Feb 29, 1840 Bellefontaine Gazette and Logan Co. Advertiser Jan 30, 1836 – Sept 16, 1837 Bellefontaine Republican Oct. 27,1854 – Jan 2 1894 Feb 26, 1897 – June 3, 1898 Sept. 28, 1900 – May 29, 1904 Bellefontaine Republican and Logan Register July 30, 1830 – Jan 15, 1831 Logan County Gazette June 9, 1854 – June 6, 1857 June 9, 1860 – Sept 18, 1863 Logan County Index Nov 19, 1885 – Jan 26, 1888 Logan Democrat Jan 4, 1843 – May 10, 1843 Logan Gazette Apr 4, 1840 – Mar 6, 1841 Jun 7, 1850 – Jun 4, 1852 Washington Republican and Guernsey Recorder July 4, 1829 – Dec 26, 1829 Weekly Examiner Jan 5, 1912 – Dec 31, 1915 March -

Historic Cemetery Resources

HISTORIC CEMETERY RESOURCES Technical Paper No. 11 Historic Preservation Program, Department of Natural Resources & Parks, 20l S. Jackson Street, Suite 700, Seattle, WA 98104, 206-477-4538 | TTY Relay: 711 Introduction Cemeteries and funerary objects are often of value beyond their traditional role as personal and family memorials or religious sacramentals. They may be historically significant as landmarks, designed landscapes or as repositories of historical information relating to communities, ethnic heritage and other heritage topics. The following resources have been compiled for individuals and organizations interested in cemetery records, research and preservation. Records & Research Area genealogical societies, museums, historical societies, pioneer associations, libraries and hereditary associations often have records and publications of interest. Among the organizations with information on cemeteries are: Seattle Genealogical Society, P.O. Box 15329, Seattle WA 98115-0329 South King County Genealogical Society, P.O. Box 3174, Kent, WA 98089-0203 Eastside Genealogical Society. P.O. Box 374, Bellevue, WA 98009-0374 Seattle Public Library, 1000 Fourth Avenue, Seattle, WA 98104-1109 Pioneer Association of the State of Washington, 1642 43rd Avenue E., Seattle, WA 98112 Fiske Genealogical Foundation, 1644 43rd Avenue E., Seattle, WA 98112-3222 Many historical societies and museum groups around King County have been instrumental in preserving and maintaining cemeteries. The Association of King County Historical Organizations (www.akcho.org) maintains a directory of area historical museums and organizations. A directory of historical organizations can also be found on the internet at www.historylink.org A number of churches and religious organizations own and operate cemeteries and maintain records of value to cemetery research. -

Development Site in Seattle's Wallingford Neighborhood

DEVELOPMENT SITE IN SEATTLE’S WALLINGFORD NEIGHBORHOOD INVESTMENT OVERVIEW 906 N 46th Street Seattle, Washington Property Highlights • The property is centrally located at the junction of three • 10 minutes to Downtown Seattle of the most desirable neighborhoods in Seattle: Phinney • Major employers within 10 minutes: University of Ridge, Fremont and Green Lake. Home prices in these Washington, Google, Amazon, Tableau, Facebook, Pemco neighborhoods range from $678,000 to $785,000, all Insurance and Nordstrom. above the city average of $626,000. • Site sits at the intersection of major bus line; Rapid Ride • 0.11 acres or 5,000 SF, tax parcel 952110-1310 runs both north and south on Aurora Avenue and the 44 • Zoned C1-40 runs east and west on 46th/45th Avenue. Employment • One of the largest employers in the • New Seattle development to add state of Washington 30,000+ jobs • 30,000+ full-time employees • 1,900+ full-time employees • 3 minutes from site • 2 minutes from site • Largest private employer in the Seattle • Business intelligence and analytics Metro area software headquarters in Seattle • 25,000+ full-time employees • 1,200+ full-time employees • 2 minutes from site • 2 minutes from site • Running shoe/apparel headquartered • One of ten office locations in North next to Gas Works Park America with a focus on IT support • 1,000+ full-time employees • 1,000+ full-time employees • 2 minutes from site • 2 minutes from site Dining and Retail Nearby Attractions Zoning C1-40 (Commercial 1) Wallingford district is within minutes of The 90-acre Woodland Park lies just north An auto-oriented, primarily retail/ many of Seattle's most popular attractions of Wallingford’s northern border, and service commercial area that serves and shopping areas. -

Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report

City of Madison, Wisconsin Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report By Jennifer L. Lehrke, AIA, NCARB, Rowan Davidson, Associate AIA and Robert Short, Associate AIA Legacy Architecture, Inc. 605 Erie Avenue, Suite 101 Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081 and Jason Tish Archetype Historic Property Consultants 2714 Lafollette Avenue Madison, Wisconsin 53704 Project Sponsoring Agency City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development 215 Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard Madison, Wisconsin 53703 2017-2020 Acknowledgments The activity that is the subject of this survey report has been financed with local funds from the City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development. The contents and opinions contained in this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the city, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the City of Madison. The authors would like to thank the following persons or organizations for their assistance in completing this project: City of Madison Richard B. Arnesen Satya Rhodes-Conway, Mayor Patrick W. Heck, Alder Heather Stouder, Planning Division Director Joy W. Huntington Bill Fruhling, AICP, Principal Planner Jason N. Ilstrup Heather Bailey, Preservation Planner Eli B. Judge Amy L. Scanlon, Former Preservation Planner Arvina Martin, Alder Oscar Mireles Marsha A. Rummel, Alder (former member) City of Madison Muriel Simms Landmarks Commission Christina Slattery Anna Andrzejewski, Chair May Choua Thao Richard B. Arnesen Sheri Carter, Alder (former member) Elizabeth Banks Sergio Gonzalez (former member) Katie Kaliszewski Ledell Zellers, Alder (former member) Arvina Martin, Alder David W.J. McLean Maurice D. Taylor Others Lon Hill (former member) Tanika Apaloo Stuart Levitan (former member) Andrea Arenas Marsha A. -

Kark's Canoeing and Kayaking Guide to 309 Wisconsin Streams

Kark's Canoeing and Kayaking Guide to 309 Wisconsin Streams By Richard Kark May 2015 Introduction A Badger Stream Love Affair My fascination with rivers started near my hometown of Osage, Iowa on the Cedar River. High school buddies and I fished the river and canoe-camped along its lovely limestone bluffs. In 1969 I graduated from St. Olaf College in Minnesota and soon paddled my first Wisconsin stream. With my college sweetheart I spent three days and two nights canoe- camping from Taylors Falls to Stillwater on the St. Croix River. “Sweet Caroline” by Neil Diamond blared from our transistor radio as we floated this lovely stream which was designated a National Wild and Scenic River in 1968. Little did I know I would eventually explore more than 300 other Wisconsin streams. In the late 1970s I was preoccupied by my medical studies in Milwaukee but did find the time to explore some rivers. I recall canoeing the Oconto, Chippewa, Kickapoo, “Illinois Fox,” and West Twin Rivers during those years. Several of us traveled to the Peshtigo River and rafted “Roaring Rapids” with a commercial company. At the time I could not imagine riding this torrent in a canoe. We also rafted Piers Gorge on the Menomonee River. Our guide failed to avoid Volkswagen Rock over Mishicot Falls. We flipped and I experienced the second worst “swim” of my life. Was I deterred from whitewater? Just the opposite, it seems. By the late 1970s I was a practicing physician, but I found time for Wisconsin rivers. In 1979 I signed up for the tandem whitewater clinic run by the River Touring Section of the Sierra Club’s John Muir Chapter. -

Discover the Possibilities Seattle Children’S Livable Streets Initiative

Livable Streets Workshop Discover the Possibilities Seattle Children’s Livable Streets Initiative For more information: Thank you to our Community Co-Sponsors http://construction.seattlechildrens.org/livablestreets/ Bicycle Alliance of Washington Cascade Bicycle Club Paulo Nunes-Ueno Feet First Director | Transportation Hawthorne Hills Community Council Seattle Children’s ITE UW Student Chapter 206-987-5908 Laurelhurst Community Club [email protected] Laurelhurst Elementary PTA Laurelhurst Elementary Safe Routes to School Public Health Seattle & King County Seattle Community Council Federation Seattle Department of Transportation Seattle Parks Foundation Sierra Club - Cascade Chapter Streets for All Seattle Sustainable Northeast Seattle Transportation Choices Coalition Transportation Northwest Undriving.org View Ridge Community Council Wedgwood Community Council 2 Table of Contents Seattle Children’s Livable Streets Initiative Safe crossings of major arterials What is Seattle Children’s Livable Streets Initiative?.....……4 Theme map: Safe crossings of major arterials ..………..…19 Public Involvement …..…….………..………………………...6 Project 7: NE 52nd St & Sand Point Way NE: Potential Projects themes and map …..…....…….………….7 Pedestrian crossing signal …………………......………...20 Project 8: 40th Ave NE & Sand Point Way NE: New signal and redesigned intersection…...……………21 Neighborhood Green Streets connecting Project 9: NE 45th St from 40th Ave NE to 47th Ave NE: parks, schools, and trails Crosswalks and curb bulbs.………...…………………….22 Project -

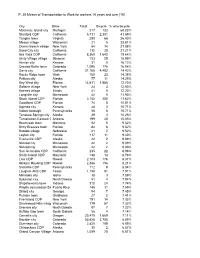

Copy of Censusdata

P. 30 Means of Transportation to Work for workers 16 years and over [16] City State Total: Bicycle % who bicycle Mackinac Island city Michigan 217 132 60.83% Stanford CDP California 5,711 2,381 41.69% Tangier town Virginia 250 66 26.40% Mason village Wisconsin 21 5 23.81% Ocean Beach village New York 64 14 21.88% Sand City city California 132 28 21.21% Isla Vista CDP California 8,360 1,642 19.64% Unity Village village Missouri 153 29 18.95% Hunter city Kansas 31 5 16.13% Crested Butte town Colorado 1,096 176 16.06% Davis city California 31,165 4,493 14.42% Rocky Ridge town Utah 160 23 14.38% Pelican city Alaska 77 11 14.29% Key West city Florida 14,611 1,856 12.70% Saltaire village New York 24 3 12.50% Keenes village Illinois 41 5 12.20% Longville city Minnesota 42 5 11.90% Stock Island CDP Florida 2,152 250 11.62% Goodland CDP Florida 74 8 10.81% Agenda city Kansas 28 3 10.71% Volant borough Pennsylvania 56 6 10.71% Tenakee Springs city Alaska 39 4 10.26% Tumacacori-Carmen C Arizona 199 20 10.05% Bearcreek town Montana 52 5 9.62% Briny Breezes town Florida 84 8 9.52% Barada village Nebraska 21 2 9.52% Layton city Florida 117 11 9.40% Evansville CDP Alaska 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% San Geronimo CDP California 245 22 8.98% Smith Island CDP Maryland 148 13 8.78% Laie CDP Hawaii 2,103 176 8.37% Hickam Housing CDP Hawaii 2,386 196 8.21% Slickville CDP Pennsylvania 112 9 8.04% Laughlin AFB CDP Texas 1,150 91 7.91% Minidoka city Idaho 38 3 7.89% Sykeston city North Dakota 51 4 7.84% Shipshewana town Indiana 310 24 7.74% Playita comunidad (Sa Puerto Rico 145 11 7.59% Dillard city Georgia 94 7 7.45% Putnam town Oklahoma 27 2 7.41% Fire Island CDP New York 191 14 7.33% Shorewood Hills village Wisconsin 779 57 7.32% Grenora city North Dakota 97 7 7.22% Buffalo Gap town South Dakota 56 4 7.14% Corvallis city Oregon 23,475 1,669 7.11% Boulder city Colorado 53,828 3,708 6.89% Gunnison city Colorado 2,825 189 6.69% Chistochina CDP Alaska 30 2 6.67% Grand Canyon Village Arizona 1,059 70 6.61% P. -

Seattle Tilth. Garden Renovation Plan. Phase 1

seattle tilth. phase 1. conceptual plan. garden renovation plan. seattle tilth. garden renovation plan. phase 1. conceptual plan. acknowledgements. This planning effort was made possible through the support of the City of Seattle Department of Neighborhoods’ Small and Simple Grant and the matching support of members, volunteers and friends of Seattle Tilth. A special thanks to the following gardening experts, landscape architects and architects for their assistance and participation in planning efforts: Carolyn Alcorn, Walter Brodie, Daniel Corcoran, Nancy Evans, Willi Evans Galloway, Eric Higbee, Katrina Morgan, Joyce Moty, Debra Oliver, Cheryl Peterson, Alison Saperstein, Gil Schieber, Brian Shapley, Lisa Sidlauskas, Craig Skipton, Elaine Stannard, Howard Stenn, Jill Stenn, Bill Thorness, Cathy Tuttle, Faith VanDePull, Linda Versage, Lily Warner, Carl Woestwin and Livy Yueh. Staff leadership provided by Kathy Dang, Karen Luetjen, Katie Pencke and Lisa Taylor. Community partners: Historic Seattle, Wallingford Community Senior Center, Wallingford P-Patch, Meridian School, Wallingford Community Council and all of our great neighbors. Many thanks to Peg Marckworth for advice on branding, Allison Orr for her illustrations and Heidi Smets for graphic design. Photography by Seattle Tilth, Heidi Smets, Amy Stanton and Carl Woestwin. We would like to thank the 2008 Architecture Design/Build Studio at the University of Washington for their design ideas and illustration. We would like to thank Royal Alley-Barnes at the City of Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation for reviewing our grant application prior to submittal. written by nicole kistler © 2008 by seattle tilth all rights reserved Seattle Tilth 4649 Sunnyside Avenue North Seattle WA 98103 www.seattletilth.org May 30, 2008 Seattle Tilth is a special place for me. -

Americanization and Cultural Preservation in Seattle's Settlement House: a Jewish Adaptation of the Anglo-American Model of Settlement Work

The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare Volume 26 Issue 3 September Article 3 September 1999 Americanization and Cultural Preservation in Seattle's Settlement House: A Jewish Adaptation of the Anglo-American Model of Settlement Work Alissa Schwartz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Alissa (1999) "Americanization and Cultural Preservation in Seattle's Settlement House: A Jewish Adaptation of the Anglo-American Model of Settlement Work," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 26 : Iss. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol26/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you by the Western Michigan University School of Social Work. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Americanization and Cultural Preservation in Seattle's Settlement House: A Jewish Adaptation of the Anglo-American Model of Settlement Work ALISSA SCHWARTZ New York City This articleexamines the dual agendas of Americanization and preserva- tion of Ashkenazic Jewish culture through an historicalanalysis of the work of Seattle's Settlement House, a social service center founded in 1906 by elite, Americanized Jews to serve poorer, immigrant Jews of Ashkenazic and Sephardic origin. Such analysis is set against the ideologicalbackdrop of Anglo-Americanism which pervaded the field of social work in its early efforts at self-definition and professionalization.Particular attention is paid to the role of the arts at Settlement House, with comparisons to Chicago's Hull-House, the prototypical American settlement operating at the turn of the century. This case study analyzes a German Jewish adaptationof an Anglo-American, Christian model of social work. -

The Artists' View of Seattle

WHERE DOES SEATTLE’S CREATIVE COMMUNITY GO FOR INSPIRATION? Allow us to introduce some of our city’s resident artists, who share with you, in their own words, some of their favorite places and why they choose to make Seattle their home. Known as one of the nation’s cultural centers, Seattle has more arts-related businesses and organizations per capita than any other metropolitan area in the United States, according to a recent study by Americans for the Arts. Our city pulses with the creative energies of thousands of artists who call this their home. In this guide, twenty-four painters, sculptors, writers, poets, dancers, photographers, glass artists, musicians, filmmakers, actors and more tell you about their favorite places and experiences. James Turrell’s Light Reign, Henry Art Gallery ©Lara Swimmer 2 3 BYRON AU YONG Composer WOULD YOU SHARE SOME SPECIAL CHILDHOOD MEMORIES ABOUT WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO SEATTLE? GROWING UP IN SEATTLE? I moved into my particular building because it’s across the street from Uptown I performed in musical theater as a kid at a venue in the Seattle Center. I was Espresso. One of the real draws of Seattle for me was the quality of the coffee, I nine years old, and I got paid! I did all kinds of shows, and I also performed with must say. the Civic Light Opera. I was also in the Northwest Boy Choir and we sang this Northwest Medley, and there was a song to Ivar’s restaurant in it. When I was HOW DOES BEING A NON-DRIVER IMPACT YOUR VIEW OF THE CITY? growing up, Ivar’s had spokespeople who were dressed up in clam costumes with My favorite part about walking is that you come across things that you would pass black leggings. -

FRITZ HEDGES WATERWAY PARK a Place Where Urban Life and Nature Converge U DISTRICT UNION BAY NATURAL AREA

FRITZ HEDGES WATERWAY PARK A Place Where Urban Life and Nature Converge U DISTRICT UNION BAY NATURAL AREA UNIVERSITY TO LAKE WASHINGTON OF WASHINGTON UNION BAY SITE PRIOR TO DEVELOPMENT WASHINGTON PARK ARBORETUM PORTAGE BAY MONTLAKE PLAYFIELD Gas Works Park TO PUGET SOUND TO CITY CENTER LAKE UNION Waterfront Context The park is located along an ecological and recreational corridor connecting Puget Sound and Lake Washington. Linking campus, neighborhood, water, and regional trails, the park is an oasis amidst a heavily developed and privatized shoreline. To transit and U District To Hospital Burke Gilman Trail Brooklyn Ave Future Campus Waterfront Trail Green Sakuma Viewpoint NE Boat St Pier Beach Kayak Launch University District Connections The park is designed to connect seamlessly to UW’s evolving Innovation District. Park access is provided via many modes of transportation, including the Burke-Gilman multi-use trail, the pedestrian oriented Brooklyn Green Street, and new U-District transit. Marine Studies Building Fisheries Research and Fishery Science Teaching Building Building NE Boat Street a e c b d f a Drop-Off Plaza with Kayak Slide b Picnic Terrace c Play Grove d Beachfront Terraces e Portage Trail and Meadow f Deck & Pier Site Plan The site is designed to feel larger than its modest two acres, with a variety of gathering places, destinations, landscape typologies and views. Cultural History The site design honors its notable historic transformation – the shoreline once supported canoe portage and cultivated meadows, as well as timber processing, Bryant’s Marina, and a Chris-Craft distribution center that brought recreational boating to Seattle’s middle class. -

Preservationists: Sharpening Our Skills Or Finding Continuing Education

Preservationists: Sharpening our skills or finding continuing education training (whether for ourselves or others) should be a high priority. To make this chore easier, I have compiled a list of activities in the Western United States or those that have special significance. Please take the time to review the list and follow the links. The following is a list of activities you should strongly consider participating in or send a delegate to represent your organization. There are many other training opportunities on the East Coast and if you need more information you can either follow the links or contact me specifically about your needs. The list is not comprehensive and you should check DAHP’s website for updates. For more information contact Russell Holter 360-586-3533. Clatsop Community College in Astoria, Oregon, now offers a Certificate and an Associate’s Degree in Historic Preservation. For more information about their class offerings, please see their website www.clatsopcc.edu. There could be scholarship opportunities available depending upon which course interests you. Please enquire with DAHP or visit the website associated with each listing. February 22 Preserving Stain Glass Historic Seattle Seattle, WA www.historicseattle.org February 24-26 Section 106: Agreement Documents National Preservation Institute Honolulu, HI www.npi.org February 25 Historic Structures Reports National Preservation Institute Los Angeles, CA www.npi.org February 26-27 Preservation Maintenance National Preservation Institute Los Angeles, CA www.npi.org