National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parks and Recreation

PARKS AND RECREATION Parks and Recreation Overview of Facilities and Programs The Department of Parks and Recreation manages 400 parks and open areas in its approximately 6,200 acres of property throughout the City, works with the public to be good stewards of the park system, and provides safe and welcoming opportunities for the public to play, learn, contemplate, and build community. The park system comprises about 10% of the City’s land area; it includes 485 buildings, 224 parks, 185 athletic fields, 122 children's play areas, 24 community centers, 151 outdoor tennis courts, 22 miles of boulevards, an indoor tennis center, two outdoor and eight indoor swimming pools, four golf courses, studios, boat ramps, moorage, fishing piers, trails, camps, viewpoints and open spaces, a rock climbing site, a conservatory, a classical Japanese garden, and a waterfront aquarium. The development of this system is guided by the Seattle Parks & Recreation Plan 2000, the 38 neighborhood plans, the Joint Athletic Facilities Development Program with the Seattle School District, the 1999 Seattle Center and Community Centers Levy, the 2000 Parks Levy, and DPR’s annual update to the Major Maintenance Plan. 2000 Parks Levy In November 2000, Seattle voters approved a $198.2 million levy lid lift for Parks and Recreation. The levy closely follows the plan forged by the Pro Parks 2000 Citizens Planning Committee. The levy is designed to fund more than 100 projects to improve maintenance and enhance programming of existing parks, including the Woodland Park Zoo; acquire, develop and maintain new neighborhood parks, green spaces, playfields, trails and boulevards; and add out-of-school and senior activities. -

A Driving Force

N011V&Then byPaulDorpat T H E N : A caravan of motorcars featuring the Seattle Press Club in at least one pennant proceeds north past Mount Baker on a new Lake Washington Boulevard. The lakeshore was considerably changed in 1916 when the lake was lowered for the opening of the Lake Washington Ship Canal. NOW: Cars still make the scenic loop along the lake. A Driving Force 0 5 the parkway the Olmsted Brothers envisioned ~ ~~~~~!~~;~rs~ ~~e ~a~~~~~e~~~~~e~~ when they planned the city's parks and boule gers or even the occasion that prompted such vards in the early 20th century. Their highest a long caravan to snake along Lake Wash ambitions were to purchase the entire west ington Boulevard through the Mount Baker side of the lake up to the ridge between Col cutves and into Colman Park. man and Leschi parks and carry the boulevard I do, however, speculate. The year may be to a scenic "crestline." Instead, the parkway 1909, when thispartofthe boulevard was new. was developed into a string of parks that often If so, then the motorcade is probably headed meanders with the boulevard. for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, which When the lake was lowered 9 feet in 1916, opened chat spring on the University of Wash the concrete and riprap seawalls were exposed. ington campus. Pieces of the boulevard were Here at Mount Baker the seawall was kept, and rushed to completion so processions like this a new, landscaped slope drops from it to the one could cover the distance from Wetmore shoreline. -

Discovery Park

Final Vegetation Management Plan Discovery Park Prepared for: Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation Seattle, Washington Prepared by: Bellevue, Washington March 5, 2002 Final Vegetation Management Plan Discovery Park Prepared for: Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation 100 Dexter Seattle, Washington 98109 Prepared by: 11820 Northup Way, Suite E300 Bellevue, Washington 98005-1946 425/822-1077 March 5, 2002 This document should be cited as: Jones & Stokes. 2001. Discovery Park. Final Vegetation Management Plan. March 5. (J&S 01383.01.) Bellevue, WA. Prepared for Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation, Seattle, WA. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION AND APPROACH........................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction....................................................................................................................1 1.2 Approach .......................................................................................................................2 2 EXISTING CONDITIONS AND RECENT VEGETATION STUDIES ........................................3 2.1 A Brief Natural History of Discovery Park .........................................................................3 2.2 2001 Vegetation Inventory ...............................................................................................4 2.3 Results of Vegetation Inventory ........................................................................................4 2.3.1 Definitions ......................................................................................................4 -

History Summary Sand Point Peninsula

HISTORY SUMMARY SAND POINT PENINSULA PRE-EURO AMERICAN SETTLEMENT POST-WAR • Native American group associated with —hloo-weelth-AHBSH“ peoples inhabited • 1947, rumored that NAS Seattle to be closed due to creation of Air Force three longhouses along Wolf Bay, immediately south of Sand Point • 1950, station scheduled for deactivation, delayed due to Korean War th MID-1800S EXPLORATION • 1950, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service established research laboratory NE 65 St. • 1850, first likely Euro-American sighting of peninsula, name Sand Point used • 1952, base closed except for Naval Reserve activities late 1950s, rumors of jet • 1855, U.S. Government Land Office surveyed Sand Point aircraft use, requiring extended runways, jet fuel storage EURO-AMERICAN SETTLEMENT • 1965 - —Outdoor Recreation and Open Space Plan“, Seattle Park Department • 1868, William Goldmyer homesteaded 81 acres immediately south of Pontiac and Seattle Planning Commission, identified Naval Air Station for major park Bay development • 1886-90, shipyard, Pontiac Brick and Tile Company, Pontiac Post Office • 1969, main airstrip resurfaced and extended to 4,800 feet, estimated cost established northwest part of peninsula $500,000 • 1914, Pontiac Brick and Tile Company closed MILITARY TO CIVILIAN CONVERSION • 1910s to early 1920‘s, four families resided northwest portion of Sand Point • June 30, 1970, air station deactivated, all flight operations ended, surplus 347 • 1918 to 1926, Carkeek Park located on the northwestern part of peninsula acres EARLY AIRFIELD DEVELOPMENT • 1975, 196 acres of the station transferred to the City of Seattle for Sand Point • Late 1910s to 1920s King County acquired small farms on Sand Point peninsula Park • June 19, 1920, groundbreaking ceremony with symbolic tree cutting and first • 1975, Sand Point Park Master Plan, proposed 75-acre Sports Meadow, tennis aircraft landing, station size 400 acres courts; neighborhood park, maintenance complex, and restaurant. -

3242 Eastlake Commercial Condominium SEATTLE CBD

3242 Eastlake Commercial Condominium SEATTLE CBD CAPITOL HILL LIGHT CAPITOL HILL RAIL STATION SOUTH LAKE UNION LAKE UNION EASTLAKE UNIVERSITY OF 3242 FREMONT WASHINGTON Eastlake Commercial Condominium U DISTRICT WALLINGFORD ROOSEVELT OFFERING Paragon Real Estate Advisors is proud to exclusively offer for sale the Eastlake Commercial Condominium. This 2,830 square foot space is currently occupied by the 4.7 star Sebi’s Bistro, a popular polish restaurant. The property is a short walk to the University of Washington and all the great amenities that Eastlake has to offer. This commercial space is located in one of Eastlake’s most significant buildings. The property was remodeled in the 1920’s by Frederick Anhalt and is believed to be Anhalt’s first building. The property is now know as the Martello Condominiums. This A+ location offers an investor the opportunity to own a commercial space with a great NNN tenant. NAME Eastlake Commercial Condominium ADDRESS 3242 Eastlake Ave E, Seattle WA 98102 BUILT 1916/1990 SQUARE FEET 2,830 Total Net Rentable PRICE $1,099,950 PRICE PER FOOT $388.67 CURRENT GRM/CAP 13.42/6.09% MARKET GRM/CAP 10.09/7.46% This information has been secured from sources we believe to be reliable, but we make no representations or warranties, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy of the information. References to square footage or age are approximate. Buyer must verify all information and bears all risk for inaccuracies. INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS A+ location One of Eastlake’s most significant buildings Frederick Anhalt’s first building 2,830 net rentable square feet $23 NNN lease 6.09% Cap rate Highly visible corner location 3 story, stucco clad building Steep gable roofs and distinctive Norman French appearance Located on major bus routes Close to the CBD and the University of WA 3242 Eastlake Commercial Condominium LOCATION HIGHLIGHTS For the past few decades, it’s been like one long episode of “Extreme Makeover: Neighborhood Edition” in Eastlake. -

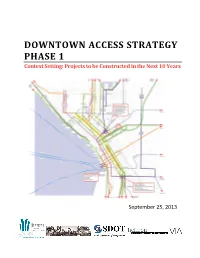

Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to Be Constructed in the Next 10 Years Table of Contents

DOWNTOWN ACCESS STRATEGY PHASE 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years September 25, 2013 Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 II. Review of Existing Plans, Projects, and Programs ......................................... 2 III. Potential Construction Concerns and Opportunities .................................. 3 A. Existing Construction Planning Tools 3 B. SDOT’s Construction Hub Coordination Program 4 C. Construction Mitigation Strategies Used by Other Cities 7 D. Potential Construction Conflicts and Opportunities 10 IV. Future Transportation Network Opportunities ......................................... 12 A. North Downtown 12 B. Denny Triangle / Westlake Hub 14 C. Pioneer Square / Chinatown-ID 15 D. Downtown Core and Waterfront 16 V. Future Phases of Downtown Access Strategy ............................................. 18 A. Framework for Phase 2 (2014 through 2016) 18 B. Framework for Phase 3 (Beyond 2016) 19 - i - September 25, 2013 Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years I. INTRODUCTION Many important and long planned transportation and development projects are scheduled for con- struction in Downtown Seattle in the coming years. While these investments are essential to support economic development and job growth and to enhance Downtown’s stature as the region’s premier location to live, work, shop and play, in the short-term they present complicated challenges for con- venient and reliable access to and through Downtown. The Downtown Seattle Association (DSA) and its partners, Historic South Downtown (HSD) and the Seat- tle Department of Transportation (SDOT), seek to ensure that Downtown Seattle survives and prospers during the extraordinarily high level of construction activity that will occur in the coming years. -

Carkeek Park

CARKEEK PARK FOREST MANAGEMENT PLAN Update 2007 2 This Forest Management Plan is dedicated to Nancie Hernandez in grateful appreciation for 13 years of Park Maintenance and volunteer guidance. LAN Front cover photos taken in subunits: 4 B 1 C 1 B 3 A 1 C 3 CARKEEK PARK FOREST MANAGEMENT PLAN Created by Peter Noonan, March – December 2002 Updated by Lex Voorhoeve, December 2005 – November 2007 Prepared for: • Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation • Carkeek Park Advisory Council Funding sources: Carkeek Park Advisory Council Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation, Urban Forestry Unit Seattle Department of Neighborhoods Matching Fund NOTE Like any forest management plan, this is a dated document, now describing the situation by the end of 2007. Over the next ten years big changes are expected in the Carkeek forest, particularly due to the over-mature Alder/Maple forest declining. Updating this document in response to those changes will likely need to occur every five years. RECOMMENDATION The non-forested units in Carkeek Park include unique wetland and riparian habitat, valuable to salmon and other wildlife. A management plan to address those units would make an excellent companion to this document. Diagrams by Peter Noonan Maps by Dale Johnson Photos and drawings by Lex Voorhoeve Plant Palettes, Appendix 5, completed by Doug Gresham Photo 1. Jacobo switchback between subunits 1B and 1C, installed by the Parks Trails Program; volunteer crew led by Jacobo Jimenez. 4 Figure 1. Carkeek Park Trails Map 5 SUMMARY 7 1. INTRODUCTION 7 2. BACKGROUND 8 HISTORY 8 PARK USE 8 PHYSICAL NATURE 8 SOIL STRATIFICATION 9 LANDSLIDES 9 SEDIMENTATION 10 FORESTS 10 A SHORT HISTORY 10 PRESENT DAY 11 RED ALDER STANDS 13 BIG LEAF MAPLE / RED ALDER STANDS 14 DECIDUOUS / CONIFEROUS MIXED STANDS 15 CONIFEROUS STANDS 15 WILDLIFE 15 MIGRATORY BIRDS 15 RESIDENT SPECIES 16 3. -

The Artists' View of Seattle

WHERE DOES SEATTLE’S CREATIVE COMMUNITY GO FOR INSPIRATION? Allow us to introduce some of our city’s resident artists, who share with you, in their own words, some of their favorite places and why they choose to make Seattle their home. Known as one of the nation’s cultural centers, Seattle has more arts-related businesses and organizations per capita than any other metropolitan area in the United States, according to a recent study by Americans for the Arts. Our city pulses with the creative energies of thousands of artists who call this their home. In this guide, twenty-four painters, sculptors, writers, poets, dancers, photographers, glass artists, musicians, filmmakers, actors and more tell you about their favorite places and experiences. James Turrell’s Light Reign, Henry Art Gallery ©Lara Swimmer 2 3 BYRON AU YONG Composer WOULD YOU SHARE SOME SPECIAL CHILDHOOD MEMORIES ABOUT WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO SEATTLE? GROWING UP IN SEATTLE? I moved into my particular building because it’s across the street from Uptown I performed in musical theater as a kid at a venue in the Seattle Center. I was Espresso. One of the real draws of Seattle for me was the quality of the coffee, I nine years old, and I got paid! I did all kinds of shows, and I also performed with must say. the Civic Light Opera. I was also in the Northwest Boy Choir and we sang this Northwest Medley, and there was a song to Ivar’s restaurant in it. When I was HOW DOES BEING A NON-DRIVER IMPACT YOUR VIEW OF THE CITY? growing up, Ivar’s had spokespeople who were dressed up in clam costumes with My favorite part about walking is that you come across things that you would pass black leggings. -

City of Seattle Edward B

City of Seattle Edward B. Murray, Mayor Finance and Administrative Services Fred Podesta, Director July 25, 2016 The Honorable Tim Burgess Seattle City Hall 501 5th Ave. Seattle, WA 98124 Councilmember Burgess, Attached is an annual report of all real property under City ownership. The annual review supports strategic management of the City’s real estate holdings. Because City needs change over time, the annual review helps create opportunities to find the best municipal use of each property or put it back into the private sector to avoid holding properties without an adopted municipal purpose. Each January, FAS initiates the annual review process. City departments with jurisdiction over real property assure that all recent acquisitions and/or dispositions are accurately represented, and provide current information about each property’s current use, and future use, if identified. Each property is classified based on its level of utilization -- from Fully Utilized Municipal Use to Surplus. In addition, in 2015 and 2016, in conjunction with CBO, OPI, and OH, FAS has been reviewing properties with the HALA recommendation on using surplus property for housing. The attached list has a new column that groups excess, surplus, underutilized and interim use properties into categories to help differentiate the potential for various sites. Below is a matrix which explains the categorization: Category Description Difficult building site Small, steep and/or irregular parcels with limited development opportunity Future Use Identified use in the future -

Report on Designation Lpb 11/12

REPORT ON DESIGNATION LPB 11/12 Name and Address of Property: Fashioncraft Building/Recovery Cafe 2022 Boren Avenue Legal Description: Lots 3 and 4 lying West of Fairview Avenue, Block 53 of the Plat of the Second Addition to the Town of Seattle Laid Off by the Heirs of Sarah A. Bell, according to the Plat thereof recorded in Volume 1 of Plats, Page 121, in King County, Washington. At the public meeting held on January 4, 2012 the City of Seattle's Landmarks Preservation Board voted to approve designation of the Fashioncraft Building/Recovery Café at 2022 Boren Avenue as a Seattle Landmark based upon satisfaction of the following standards for designation of SMC 25.12.350: C. It is associated in a significant way with a significant aspect of the cultural, political, or economic heritage of the community, City, state, or nation; and D. It embodies the distinctive visible characteristics of an architectural style, period, or of a method of construction; and F. Because of its prominence of spatial location, contrasts of siting, age, or scale, it is an easily identifiable visual feature of its neighborhood or the City and contributes to the distinctive quality or identity of such neighborhood or the City. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION Overall Aspect The Fashioncraft Building at 2022 Boren Avenue is sited on the triangular lot, bounded by Denny Way, Fairview Avenue and Boren Avenue. The building, whose plan is basically a chamfered right triangle, is one story in height, but has a basement. The exterior is primarily clad in light brown brick with cast stone ornament, which echoes Churriguresque decoration or the Spanish Eclectic work of American architects, such as Bertram Goodhue. -

Local Places to Visit Around Seattle

Eastside Literacy Talk Time Spring 2006 Talk Time Topic: Local Places to Visit around Seattle Let’s get started… Take a few minutes to think of a local place that you visited. • Where did you go, and what did you do? • Who went with you? (friends, family, etc.) • How much did it cost? • Would you recommend this place to others? Why or why not? Background: Many people go to coffee shops (Starbucks is a favorite destination) or shopping when they have cabin fever. At other times, they want a longer trip or a change of scenery so they take a day trip. Families, couples, and people of all ages enjoy seeing or doing something new. The Seattle area offers many different types of things to do and see close to home. It is possible to take a ferry, drive to the mountains, and visit the Pike Place Market all in the same day! Spend 5 minutes asking each other the following questions. Interview 2-3 people about any local trips that they have taken. Work with your Talk Time leader to complete the grid below. Share your results with the group. Name Where did you go? What did you see? Would you go again? Discussion Questions: What places would you like to visit? How can you find out more about the cost, the transportation and any other questions you might have? What activities do you enjoy doing? Do you prefer indoor or outdoor activities? What did you do in your country? Did you take local trips? Where did you go? Did you take trips in Winter? Spring? Summer? Fall? Why? Some outings are “kid friendly” and others are not. -

For Sale: $1535000

FOR SALE: $1,535,000 ALKI AVENUE REDEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY 2309 53RD AVE SW, SEATTLE, WA 98116 // ALKI BEACH NEIGHBORHOOD DOWNTOWN SEATTLE BALLARD MAGNOLIA QUEEN ANNE SUBJECT PROPERTY Scott Clements David Butler 1218 Third Avenue www.orioncp.com P// 206.445.7664 P// 206.445.7665 Suite 2200 P// 206.734.4100 [email protected] [email protected] Seattle, WA 98101 Established in 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS // INVESTMENT SUMMARY PAGE// 3 // SITE OVERVIEW PAGE// 4 // PORTFOLIO OVERVIEW PAGE// 13 // MARKET OVERVIEW PAGE// 16 // DEMOGRAPHICS PAGE// 17 2 // 2309 53RD AVE SW THE OFFERING Orion Commercial Partners is excited to offer for sale the Bungalow’s located at 2309 53rd Ave SW, Seattle WA. This rare redevelopment opportunity is located right on Alki Ave SW and has a preliminary site plan for 5 new townhomes ranging from 1,550 Square feet to 1,700 square feet. This site has unobstructed views of Puget Sound, the Olympic Mountains, Elliott Bay, Seattle and most importantly is right across the street from Alki Beach. Zoned LR2 (M), this 6,817 Square Foot lot can also be purchased as part of a 6 property portfolio of neighboring properties (details in Portfolio section). Priced at just over $225/square foot this opportunity will not last long! INVESTMENT 2309 53RD AVE SW, Address SEATTLE, WA 98116 SUMMARY Offering Price $1,535,000 Proposed # of 5 Townhome Units Price/Unit $307,000 SF Range of New 1,500 SF - 1,700 SF Townhome Units Price/SF Building $381.00 Total Land Area 6,817 SF Price Per Square $225.17 Foot Land Zoning LR2 (M) Year Built 1951 Portfolio Price 21,081,000 3 // 2309 53RD AVE SW SITE 53RD AVE SW OVERVIEW 2309 53RD AVE SW ALKI AVE SW // 10,170 VPD LR2 (M) ZONING Areas characterized by multifamily housing types in existing small-scale multifamily housing types, which are similar in character to single family zones.