Plato on Laughing at People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLATO's SYMPOSIUM J

50 ccn~ PLATO'S SYMPOSIUM j - - -- ________j e Library of Liberal Arts PLATO'S SYMPOSIUM Tran lated by BENJAMIN JOWETT With an Introduction by FULTON H. ANDERSON Professor of Philosophy, University of Toronto THE LIBERAL ARTS PRESS NEW YORK CONTENTS SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY .. .... ................................... ......... ... ........... 6 EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION ................... ............................................. 7 SYMPOSIUM APOLLODORUS 13 THE SPEECH OF PHAEDRUS ...... .......................... .......................... .. 19 THE SPEECH OF PAU ANIAS ................. ... ................................. ... .. 21 THE SPEECH OF ERYXIMACHUS 27 THE SPEECH OF ARISTOPHAN E .. ............................... .................. 30 THE SPEECH OF AGATHON ............ .............................................. .. 35 THE SPEECH OF SocRATES ................................ .. ................... ..... .. 39 THE SPEECH OF ALCIBIADES ................. ............... ... ........... ...... .... .. 55 8 PLATO INTROD CTION 9 crescendo, and culminates in the report by Socrates on wi dom and epistemology, upon all of which the Symposium ha bearing, learned from the "wi e" woman Diotima. are intertwined, we m ay set down briefly a few of the more general The dialogue i a "reported" one. Plato himself could not have principles which are to be found in it author's many-sided thought. been present at the original party. (What went on there was told The human soul, a cording to Plato, is es entially in motion. time and time again about Athens.) He was a mere boy when it It is li fe and the integration of living functions. A dead soul is a con took place. Nor could the narrator Apollodorus have been a guest; _lladiction in terms. Man throughout his whole nature is erotically he was too young at the time. The latter got his report from motivated. His "love" or desire i manifest in three mutually in Aristodemus, a guest at the banquet. -

Philosophy 320: Knowledge and Assertion

Course Syllabus: Philosophy 320: Knowledge and Assertion Matthew A. Benton [email protected] Description This 300-level upper-division undergraduate course, intended primarily for philosophy majors, will cover the literature on a fascinating question that has recently surfaced at the intersection of epistemology and philosophy of language: whether knowledge is the norm of assertion. The idea behind such a view is that in our standard conversational contexts, one who flat-out asserts that something is the case somehow represents herself as knowing that thing, and thus, there is a norm to the effect that one ought not to flat-out assert something unless one knows it. Proponents of the knowledge-norm have appealed to several strands of data from ordinary conversation practice and problematic sentences to sup- port their view; but other philosophers have leveled counterarguments. This course will evaluate the debate, including the most recent installments from the cutting edge of the philosophical literature. The course will meet a demand amongst undergraduates to study this re- cently (and hotly) debated issue: the literature relating knowledge and assertion is new enough that it is not typically covered by other undergraduate courses in epistemology or philosophy of language. It will hold special appeal for un- dergraduates with cross-disciplinary interests in language, epistemology, and communal/social normativity, and will provide a rich background for those who want to do further advanced study in philosophy or linguistics. Course Requirements Weekly readings and mandatory class attendance; students missing more than 5 class sessions will have their final grade lowered a half grade for each additional absence. -

Laughter: the Best Medicine?

Laughter: The Best Medicine? by Barbara Butler elcome to a crash COLI~SCin c~onsecli1~11cc.~ol'nvgarivc emotions. Third, Oregon Institute ofMarine Biology Gelotology 101. That isn't a using Iiumor as :I c~ol)irigs(r:itcgy n~ayalso University of Oregon typo, Gelotology (from the I~enefithealth inclirec.tly I)y moderating ad- Greek root gelos (to laugh)), is a term verse effects of stress. Finally, humor may coined in 1964 by Dr. Edith Trager and Dr. provide another indirect Ixnefit to health W.F. Fry to describe the scientific study of by increasing one's level of social support laughter. While you still can't locate this (Martin, 2002, 2004). term in the OED, you can find it on the Web. The study of humor is a science, The physiology of humor and laughter researchers publish in the Dr. William F. Fry from Stanford University psychological and physiological literature has published a number of studies of the as well as subject specific journals (e.g., physiological processes that occur dur- Humor: International Journal of Humor ing laughter and is often cited by people Research). claiming that laughter is equivalent to ex- While at the Special Libraries As- ercise. Dr. Fry states, "I believe that we do sociation annual conference last June, I not laugh merely with our lungs, or chest was able to attend a session by Elaine M. muscles, or diaphragm, or as a result of a Lundberg called Laugh For the Health of stimulation of our cardiovascular activity. It. The room was packed and she had the I believe that we laugh with our whole audience laughing and learning for the physical being. -

1 Epistemic Norms of Political Deliberation Fabienne Peter

Epistemic norms of political deliberation Fabienne Peter, University of Warwick ([email protected]) December 2020 Forthcoming in Michael Hannon and Jeroen de Ridder (eds.) Routledge Handbook of Political Epistemology (https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Handbook-of-Political- Epistemology/Hannon-Ridder/p/book/9780367345907). Please cite the published version. Abstract Legitimate political decision-making is underpinned by well-ordered political deliberation, including by the decision-makers themselves, their advisory bodies, and the public at large. But what constitutes well-ordered political deliberation? The short answer to this question is that it’s political deliberation that is governed by relevant norms. In this chapter, I first discuss different types of norms that might govern well-ordered political deliberation. I then focus on one particular type of norms: epistemic norms. My aim in this chapter is to shed light on how the validity of contributions to political deliberation depends, inter alia, on the epistemic status of the claims made. 1. Introduction Political deliberation is the broad, multi-stranded process in which political proposals get considered and critically scrutinised.1 There are many forums in which political deliberation takes place. Some of them are formal institutions of government such as the cabinet and parliament. Other forums of political deliberation include advisory bodies, government agencies, political parties and interest groups, the press and other broadcasters, and, increasingly, social media platforms. The latter are not directly associated with political 1 I have received helpful comments on an earlier version of this chapter from Jeroen de Ridder, Michael Hannon, and an external referee. I also benefitted from conversations with Nathalie Ashton, Rowan Cruft, and Jonathan Heawood in the context of our ARHC project on Norms for the New Public Sphere and from discussions at a NYU Political Economy and Political Theory workshop, especially with Dimitri Landa, Ryan Pevnick, and Melissa Schwartzberg. -

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

Norm (Philosophy) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Norm (philosophy) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Norms are concepts (sentences) of practical import, oriented to effecting an action, rather than conceptual abstractions that describe, explain, and express. Normative sentences imply "ought-to" types of statements and assertions, in distinction to sentences that provide "is" types of statements and assertions. Common normative sentences include commands, permissions, and prohibitions; common normative abstract concepts include sincerity, justification, and honesty. A popular account of norms describes them as reasons to take action, to believe, and to feel. Types of norms Orders and permissions express norms. Such norm sentences do not describe how the world is, they rather prescribe how the world should be. Imperative sentences are the most obvious way to express norms, but declarative sentences also may be norms, as is the case with laws or 'principles'. Generally, whether an expression is a norm depends on what the sentence intends to assert. For instance, a sentence of the form "All Ravens are Black" could on one account be taken as descriptive, in which case an instance of a white raven would contradict it, or alternatively "All Ravens are Black" could be interpreted as a norm, in which case it stands as a principle and definition, so 'a white raven' would then not be a raven. Those norms purporting to create obligations (or duties) and permissions are called deontic norms (see also deontic logic). The concept of deontic norm is already an extension of a previous concept of norm, which would only include imperatives, that is, norms purporting to create duties. The understanding that permissions are norms in the same way was an important step in ethics and philosophy of law. -

The Absurd Author(S): Thomas Nagel Reviewed Work(S): Source: the Journal of Philosophy, Vol

Journal of Philosophy, Inc. The Absurd Author(s): Thomas Nagel Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 68, No. 20, Sixty-Eighth Annual Meeting of the American Philosophical Association Eastern Division (Oct. 21, 1971), pp. 716-727 Published by: Journal of Philosophy, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2024942 . Accessed: 19/08/2012 01:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Philosophy, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Philosophy. http://www.jstor.org 7i6 THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY The formerstands as valid only if we can findcriteria for assigning a differentlogical formto 'allegedly' than to 'compulsively'.In this case, the criteriaexist: 'compulsively'is a predicate, 'allegedly' a sentenceadverb. But in countless other cases, counterexamplesare not so easily dismissed.Such an example, bearing on the inference in question, is Otto closed the door partway ThereforeOtto closed the door It seems clear to me that betterdata are needed beforeprogress can be made in this area; we need much more refinedlinguistic classificationsof adverbial constructionsthan are presentlyavail- able, ifour evidenceconcerning validity is to be good enough to per- mit a richerlogical theory.In the meantime,Montague's account stands: thereis no reason to thinka morerefined theory, if it can be produced, should not be obtainable within the frameworkhe has given us. -

The Historicity of Plato's Apology of Socrates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1946 The Historicity of Plato's Apology of Socrates David J. Bowman Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Bowman, David J., "The Historicity of Plato's Apology of Socrates" (1946). Master's Theses. 61. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/61 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1946 David J. Bowman !HE HISTORICITY OP PLATO'S APOLOGY OF SOCRATES BY DA.VID J. BOWJWf~ S.J• .l. !BESIS SUBMITTED Ilf PARTIAL FULFILIJIE.NT OF THB: R}gQUIRE'IIENTS POR THE DEGREE OF IIA.STER OF ARTS Ill LOYOLA UlfiVERSITY JULY 1946 -VI'fA. David J. Bowman; S.J•• was born in Oak Park, Ill1no1a, on Ma7 20, 1919. Atter b!a eleaentar7 education at Ascension School# in Oak Park, he attended LoJola AcademJ ot Chicago, graduat1DS .from. there in June, 1937. On September 1, 1937# he entered the Sacred Heart Novitiate ot the SocietJ ot Jesus at Milford~ Ohio. Por the tour Jear• he spent there, he was aoademicallJ connected with Xavier Univeraitr, Cincinnati, Ohio. In August ot 1941 he tranaterred to West Baden College o.f Lorol& Universit7, Obicago, and received the degree ot Bachelor o.f Arts with a major in Greek in Deo.aber, 1941. -

Plato's Symposium: the Ethics of Desire

Plato’s Symposium: The Ethics of Desire FRISBEE C. C. SHEFFIELD 1 Contents Introduction 1 1. Ero¯s and the Good Life 8 2. Socrates’ Speech: The Nature of Ero¯s 40 3. Socrates’ Speech: The Aim of Ero¯s 75 4. Socrates’ Speech: The Activity of Ero¯s 112 5. Socrates’ Speech: Concern for Others? 154 6. ‘Nothing to do with Human AVairs?’: Alcibiades’ Response to Socrates 183 7. Shadow Lovers: The Symposiasts and Socrates 207 Conclusion 225 Appendix : Socratic Psychology or Tripartition in the Symposium? 227 References 240 Index 249 Introduction In the Symposium Plato invites us to imagine the following scene: A pair of lovers are locked in an embrace and Hephaestus stands over them with his mending tools asking: ‘What is it that you human beings really want from each other?’ The lovers are puzzled, and he asks them again: ‘Is this your heart’s desire, for the two of you to become parts of the same whole, and never to separate, day or night? If that is your desire, I’d like to weld you together and join you into something whole, so that the two of you are made into one. Look at your love and see if this is what you desire: wouldn’t this be all that you want?’ No one, apparently, would think that mere sex is the reason each lover takes such deep joy in being with the other. The soul of each lover apparently longs for something else, but cannot say what it is. The beloved holds out the promise of something beyond itself, but that something lovers are unable to name.1 Hephaestus’ question is a pressing one. -

On Laughter Supervisor: Rebekah Humphreys Word Count: 21991

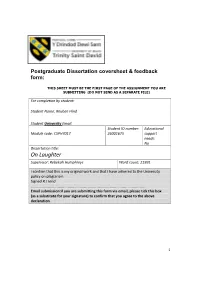

Postgraduate Dissertation coversheet & feedback form: THIS SHEET MUST BE THE FIRST PAGE OF THE ASSIGNMENT YOU ARE SUBMITTING (DO NOT SEND AS A SEPARATE FILE) For completion by student: Student Name: Reuben Hind Student University Email: Student ID number: Educational Module code: CSPH7017 26001675 support needs: No Dissertation title: On Laughter Supervisor: Rebekah Humphreys Word count: 21991 I confirm that this is my original work and that I have adhered to the University policy on plagiarism. Signed R J Hind …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Email submission:if you are submitting this form via email, please tick this box (as a substitute for your signature) to confirm that you agree to the above declaration. 1 ABSTRACT. Much of Western Philosophy has overlooked the central importance which human beings attribute to the Aesthetic experiences. The phenomena of laughter and comedy have largely been passed over as “too subjective” or highly emotive and therefore resistant to philosophical analysis, because they do not easily lend themselves to the imposition of Absolutist or strongly theory-driven perspectives. The existence of the phenomena of laughter and comedy are highly valued because they are viewed as strongly communal activities and expressions. These actually facilitate our experiences as inherently social beings, and our philosophical understanding of ourselves as beings, who experience passions and life itself amidst a world of fluctuating meanings and human drives. I will illustrate how the study of “Aesthetics” developed from Ancient Greek conceptions, through the post-Kantian and post-Romantic periods, which opened-up a pathway to the explicit consideration of the phenomena of laughter and comedy, with particular reference to the Apollonian/Dionysian conceptual schemata referred to in Nietzsche’s early works. -

On the Arrangement of the Platonic Dialogues

Ryan C. Fowler 25th Hour On the Arrangement of the Platonic Dialogues I. Thrasyllus a. Diogenes Laertius (D.L.), Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 3.56: “But, just as long ago in tragedy the chorus was the only actor, and afterwards, in order to give the chorus breathing space, Thespis devised a single actor, Aeschylus a second, Sophocles a third, and thus tragedy was completed, so too with philosophy: in early times it discoursed on one subject only, namely physics, then Socrates added the second subject, ethics, and Plato the third, dialectics, and so brought philosophy to perfection. Thrasyllus says that he [Plato] published his dialogues in tetralogies, like those of the tragic poets. Thus they contended with four plays at the Dionysia, the Lenaea, the Panathenaea and the festival of Chytri. Of the four plays the last was a satiric drama; and the four together were called a tetralogy.” b. Characters or types of dialogues (D.L. 3.49): 1. instructive (ὑφηγητικός) A. theoretical (θεωρηµατικόν) a. physical (φυσικόν) b. logical (λογικόν) B. practical (πρακτικόν) a. ethical (ἠθικόν) b. political (πολιτικόν) 2. investigative (ζητητικός) A. training the mind (γυµναστικός) a. obstetrical (µαιευτικός) b. tentative (πειραστικός) B. victory in controversy (ἀγωνιστικός) a. critical (ἐνδεικτικός) b. subversive (ἀνατρεπτικός) c. Thrasyllan categories of the dialogues (D.L. 3.50-1): Physics: Timaeus Logic: Statesman, Cratylus, Parmenides, and Sophist Ethics: Apology, Crito, Phaedo, Phaedrus, Symposium, Menexenus, Clitophon, the Letters, Philebus, Hipparchus, Rivals Politics: Republic, the Laws, Minos, Epinomis, Atlantis Obstetrics: Alcibiades 1 and 2, Theages, Lysis, Laches Tentative: Euthyphro, Meno, Io, Charmides and Theaetetus Critical: Protagoras Subversive: Euthydemus, Gorgias, and Hippias 1 and 2 :1 d. -

Plato the ALLEGORY of the CAVE Republic, VII 514 A, 2 to 517 A, 7

Plato THE ALLEGORY OF THE CAVE Republic, VII 514 a, 2 to 517 a, 7 Translation by Thomas Sheehan THE ALLEGORY OF THE CAVE SOCRATES: Next, said I [= Socrates], compare our nature in respect of education and its lack to such an experience as this. PART ONE: SETTING THE SCENE: THE CAVE AND THE FIRE The cave SOCRATES: Imagine this: People live under the earth in a cavelike dwelling. Stretching a long way up toward the daylight is its entrance, toward which the entire cave is gathered. The people have been in this dwelling since childhood, shackled by the legs and neck..Thus they stay in the same place so that there is only one thing for them to look that: whatever they encounter in front of their faces. But because they are shackled, they are unable to turn their heads around. A fire is behind them, and there is a wall between the fire and the prisoners SOCRATES: Some light, of course, is allowed them, namely from a fire that casts its glow toward them from behind them, being above and at some distance. Between the fire and those who are shackled [i.e., behind their backs] there runs a walkway at a certain height. Imagine that a low wall has been built the length of the walkway, like the low curtain that puppeteers put up, over which they show their puppets. The images carried before the fire SOCRATES: So now imagine that all along this low wall people are carrying all sorts of things that reach up higher than the wall: statues and other carvings made of stone or wood and many other artifacts that people have made.