The Sympathizer: a Dialectical Reading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Reading 2021

Shady Side Academy Senior School Summer Reading 2021 This summer, you will have the opportunity to read two (2) books before returning to classes in the fall. You will read one book to be discussed in your Fall term English class, and one to be discussed with your Advisory group. English Book: See the list below for your Form’s text. You should be prepared to discuss it in your English class, so be sure to read and annotate it in such a way that you have some knowledge of it in your working memory when you are back on campus; your fall-term English teacher will give you more details about what you will do with that knowledge when you meet him/her on the first day of classes. Above all, enjoy the reading! Advisory Book: All Form III students will read the same book; students in Forms IV, V, and VI can find their texts listed below under their individual advisor’s name. You should plan on being prepared to discuss this book with your advisory group during an extended Designated Rooms meeting during the first week of classes. Your advisor may also ask you to write up something on your text in preparation for that discussion session, perhaps in a Google document of some kind; stay tuned for details when the opening of classes draws nearer. In the meantime, please enjoy the selection your advisor has made. View the Table of Contents on the next page to see the assigned books per form and per advisory. If you are purchasing books locally, please consider supporting the following independent bookstores: City of Asylum Bookstore, Riverstone Books, -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

RHO Readers Literary Journey

RHO* Readers Literary Journey October 2020 The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien September 2020 The Bookwoman of Troublesome Creek by Kim Michelle Richardson August 2020 The Secrets We Kept by Lara Prescott July 2020 Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America by Jonathan M. Metzl June 2020 The Dutch House by Ann Patchett May 2020 The Suspect: An Olympic Bombing, the FBI, the Media, and Richard Jewell, The Man Caught in the Middle by Alexander Kent April 2020 City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert March 2020 (No meeting) February 2020 A Well-Behaved Woman: A Novel of the Vanderbilts by Therese Anne Fowler January 2020 The Secret Diary of Hendrik Groen by Hendrik Groen, 83 ¼ Yrs. Old November 2019 The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary by Simon Winchester October 2019 The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead September 2019 Metropolis by Philip Kerr August 2019 On the Porch, Under the Eave by Jane Simpson July 2019 Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens June 2019 Washington Black by Esi Edugyan May 2019 Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America by Beth Macy April 2019 Unsheltered: A Novel by Barbara Kingsolver March 2019 Macbeth / William Shakespeare's Macbeth Retold: A Novel by Jo Nesbo February 2019 Educated: A Memoir by Tara Westover January 2019 Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart November 2018 Whiskey When We're Dry by John Larsen October 2018 The Death of Democracy: Hitler’s Rise to Power and the Downfall of the Weimar -

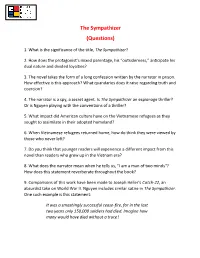

The Sympathizer (Questions)

The Sympathizer (Questions) 1. What is the significance of the title, The Sympathizer? 2. How does the protagonist’s mixed parentage, his “outsiderness,” anticipate his dual nature and divided loyalties? 3. The novel takes the form of a long confession written by the narrator in prison. How effective is this approach? What quandaries does it raise regarding truth and coercion? 4. The narrator is a spy, a secret agent. Is The Sympathizer an espionage thriller? Or is Nguyen playing with the conventions of a thriller? 5. What impact did American culture have on the Vietnamese refugees as they sought to assimilate in their adopted homeland? 6. When Vietnamese refugees returned home, how do think they were viewed by those who never left? 7. Do you think that younger readers will experience a different impact from this novel than readers who grew up in the Vietnam era? 8. What does the narrator mean when he tells us, "I am a man of two minds"? How does this statement reverberate throughout the book? 9. Comparisons of this work have been made to Joseph Heller's Catch-22, an absurdist take on World War II. Nguyen includes similar satire in The Sympathizer. One such example is this statement: It was a smashingly successful cease-fire, for in the last two years only 150,000 soldiers had died. Imagine how many would have died without a truce! Can you find other examples where the author employs similar satiric wit? What affect does such a stylistic device have on your reading? Does the black humor lessen the horror of the war, or draw more attention to it? 10. -

GMLC Kitkeeper Book Set List Audience Genre Title Author Copies Owning Library

GMLC KitKeeper Book Set List Audience Genre Title Author Copies Owning Library Adult Biography An American childhood Dillard, Annie 8 Burnham Adult Biography Becoming Obama, Michelle 10 Milton Adult Biography Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood Noah, Trevor 10 South Burlington Kimmerer, Robin Adult Biography Braiding sweetgrass 9 Fletcher Free Wall Adult Biography Calypso Sedaris, David 10 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Can't we talk about something more pleasant? [graphic novel] Chast, Roz 8 Fletcher Free Adult Biography The dawn watch : Joseph Conrad in a global war Jasanoff, Maya 8 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Dora Bruder Modiano, Patrick 5 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Educated : a memoir Westover, Tara Fletcher Free Adult Biography Educated : a memoir Westover, Tara 8 Burnham Adult Biography Endurance : a year in space, a lifetime of discovery Kelly, Scott 10 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Hidden figures Lee Shetterly, Margot 10 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Hillbilly Elegy Vance, J.D. 9 South Burlington Adult Biography Hillbilly Elegy Vance, J.D. 10 Fletcher Free Adult Biography I saw Ramallah Barghuthi, Murid 5 Fletcher Free 1 GMLC KitKeeper Book Set List Nelson, Jessica Adult Biography If only you people could follow directions : a memoir 5 Fletcher Free Hendry Adult Biography In a sunburned country Bryson, Bill 5 Fletcher Free In the garden of beasts : love, terror, and an American family Adult Biography Larson, Erik 5 Fletcher Free in Hitler's Berlin Adult Biography Just kids Smith, Patti 10 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Just mercy : a story of justice and redemption Stevenson, Bryan Fletcher Free Adult Biography March: Book One Lewis, John 10 South Burlington Adult Biography Reading Lolita in Tehran : a memoir in books Nafisi, Azar 5 Fletcher Free Boylan, Jennifer Adult Biography She's not there : a life in two genders 9 Fletcher Free Finney Adult Biography The short and tragic life of Robert Peace Hobbs, Jeff 10 Fletcher Free Those turbulent sons of freedom : Ethan Allen's Green Adult Biography Wren, Christopher S. -

SYMPATHIZER-Catalog-Pages.Pdf

APRIL A startling debut novel from a powerful new voice featuring one of the most remarkable narrators of recent fiction: a conflicted subversive and idealist working as a double agent in the aftermath of the Vietnam War The Sympathizer Viet Thanh Nguyen MARKETING Nguyen is an award-winning short story “Magisterial. A disturbing, fascinating and darkly comic take on the fall of writer—his story “The Other Woman” Saigon and its aftermath and a powerful examination of guilt and betrayal. The won the 2007 Gulf Coast Barthelme Prize Sympathizer is destined to become a classic and redefine the way we think about for Short Prose the Vietnam War and what it means to win and to lose.” —T. C. Boyle Nguyen is codirector of the Diasporic profound, startling, and beautifully crafted debut novel, The Sympathizer Vietnamese Artists Network and edits a is the story of a man of two minds, someone whose political beliefs blog on Vietnamese arts and culture clash with his individual loyalties. In dialogue with but diametrically Published to coincide with the fortieth A opposed to the narratives of the Vietnam War that have preceded it, this novel anniversary of the Fall of Saigon offers an important and unfamiliar new perspective on the war: that of a con- prepublication reading copies flicted communist sympathizer. eGalleys available on NetGalley and Edelweiss It is April 1975, and Saigon is in chaos. At his villa, a general of the South 8-city tour (Boston * New York City * Vietnamese army is drinking whiskey and, with the help of his trusted captain, Washington, D.C. -

Why Fiction Matters: Two Pulitzer-Prize Winning Authors On

Why Fiction Matters: Two Pulitzer-Prize Winning Authors on the Truth-Telling Power of Literature Arlington Public Library presents award winning authors Elizabeth Strout (April 20) and Viet Thanh Nguyen (May 3) March 28, 2017 | News Release Enjoy free author talks with Pulitzer-prize winning authors Elizabeth Strout (April 20) and Viet Thanh Nguyen (May 3) at Central Library Learn about Strout’s newest novel “Anything is Possible” and Nguyen’s new fiction work “The Refugees” Visit Library.arlingtonva.us/arlington-reads for more information Library patrons are in for a treat this spring as Arlington Public Library presents two Pulitzer-prize winning authors — Elizabeth Strout and Viet Thanh Nguyen. Both authors will be discussing their new books while addressing the truth-telling power of literature. Strout will appear on April 20, 7 p.m. and Nguyen on May 3, 7 p.m., at Central Library, Auditorium. Strout, novelist and short-story writer, winner of the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for Olive Kitteridge, will discuss why she believes a reader can find ”the truest things in good fiction, while gaining compassion through understanding the experience of others.” Strout’s newest novel in stories, Anything is Possible, to be released April 25, draws from the lives of residents of Amgash, Illinois, the same small-town setting used for My Name is Lucy Barton. Nguyen, award winning author and recipient of the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for The Sympathizer, will be joined by Arlington Public Library Director Diane Kresh in a conversation about his writings and the role of fiction in illuminating issues of consequence. -

SUMMER READING 2019 11Th and 12Th Grades

SUMMER READING 2019 11th and 12th Grades In this packet, you will find information about Summer Reading for new and returning Commonwealth students. Traditionally, we begin each school by breaking into small groups to discuss a book or books that the whole community has read. This year, each group will discuss a different book, representing a range of topics and genres, chosen by the faculty member leading the conversation. Please select one book from the “Summer Reading Discussion Groups” list and come to school prepared to share your observations! Summer break can be a wonderful time to catch up on your reading—to discover new genres or authors, to re-read old favorites, or to finally tackle a literary classic. We encourage you to explore the titles on the attached lists, which include recommendations from the library, your teachers, and your classmates. If you liked a book in one of your courses last year, you might want to try another by the same author this summer. When you return to school in the fall, your advisor will be interested to hear what you have read and your responses. These lists are also available on the library webpage (under Academics at commschool.org) where I have provided links to online ordering options for the required reading. Most books on this list will also be available at your local bookshop or library. Happy reading! Ms. Johnson PART ONE: Summer Reading Discussion Groups Each student will participate a discussion group for one of these books upon returning to school in the fall. Michael Bloomberg & Carl Pope, Climate of Hope: How Cities, Businesses, and Citizens Can Save the Planet (Ms. -

AP Literature and Composition 2020 Summer Reading Assignment

Dr. Doyle AP Literature and Composition AP Literature and Composition 2020 Summer Reading Assignment DIRECTIONS #1 Readings You will read TWO books of your choice from the lists below, a classic title and a modern title. One of your choices must be selected from the first list of classics that contains some of the most frequently referenced books on the AP Literature exam between 1970-2011. Your second choice must be a modern novel of literary merit. List 2 contains the winners of the Booker Prize and the Pulitzer Prize from the last 20 years. CHOOSE ONE TITLE FROM EACH LIST. You can either borrow books from your local library, download e-books to a device, or purchase your own hard copies to annotate in directly. How to select a book that you will enjoy from the lists below: Do not select a book at random. Although all of these titles are meritorious and significant reads, some of them you will obviously enjoy more than others based on your distinct literary tastes. If you don’t like war stories, don’t pick a war story. You can base your selection on authors that you are familiar with, on researching some of the titles that sound interesting to you, and on recommendations from friends/family that may have read these books before. #2 Dialectical Journal You will complete THREE dialectical journal entries for each book you read (that means SIX entries total: 3 for the classic title + 3 for the modern title = 6 journal entries total). A dialectical journal is a written conversation with yourself about a piece of literature that encourages the habit of reflective questioning. -

Fiction Award Winners 2019

1989: Spartina by John Casey 2016: The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen National Book 1988: Paris Trout by Pete Dexter 2015: All the Light We Cannot See by A. Doerr 1987: Paco’s Story by Larry Heinemann 2014: The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt Award 1986: World’s Fair by E. L. Doctorow 2013: Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 1985: White Noise by Don DeLillo 2012: No prize awarded 2011: A Visit from the Goon Squad “Established in 1950, the National Book Award is an 1984: Victory Over Japan by Ellen Gilchrist by Jennifer Egan American literary prize administered by the National 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding Book Foundation, a nonprofit organization.” 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout - from the National Book Foundation website. 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao 1979: Going After Cacciato by Tim O’Brien by Junot Diaz 2018: The Friend by Sigrid Nunez 1978: Blood Tie by Mary Lee Settle 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2017: Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward 1977: The Spectator Bird by Wallace Stegner 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 2016: The Underground Railroad by Colson 1976: J.R. by William Gaddis 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson Whitehead 1975: Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone 2004: The Known World by Edward P. Jones 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson The Hair of Harold Roux 2003: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay by Thomas Williams 2002: Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 2001: The Amazing Adventures of 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich 1973: Chimera by John Barth Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward 1972: The Complete Stories 2000: Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon by Flannery O’Connor 1999: The Hours by Michael Cunningham 2009: Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann 1971: Mr. -

11 AP Summer Reading 2021 Book Choices

11 AP Summer Reading 2021 Book Choices Read two of the following nonfiction books: Amoruso, #Girlboss Angelou, I Know why the Caged Bird Sings Ansari, Modern Romance Bayoumi, How does it feel to be a Problem?: Being Young and Arab in America Boo, Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity Brown, The Boys in the Boat Capote, In Cold Blood Cain, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking Coates, Between the World and Me Demick, Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea Ehrenreich, Nickle and Dimed: On (Not) Getting by in America Fey, Bossypants Fink, Five Days at Memorial: Life and Death in a Storm-Ravaged Hospital Gladwell, Blink, David and Goliath, Outliers Griffin, Black Like Me Hillenbrand, Unbroken Kingston, The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts Krakauer, Missoula: Rape and the Justice System in a College Town, Into the Wild, Into Thin Air Lamott, Bird by Bird Levitt & Dubner, Freakonomics, Think Like a Freak Lewis, Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game McBride, The Color of Water McCourt, Angela’s Ashes, Teacher Man McDougall, Born to Run Obama, Dreams from My Father Rawlence, City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World’s Largest Refugee Camp Schlosser, Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal Sedaris, Me Talk Pretty One Day Shetterly, Hidden Figures: The True Story of Four Black Women and the Space Race Smith, Ordinary Light Stevenson, Just Mercy Vance, Hillbilly Elegy Warrick, Black Flags: The Rise of ISIS Wright, Black Boy Yousafzai, -

Refocusing on Women and the Obscene in Viet Nguyen's The

Refocusing on Women and the Obscene in Viet Nguyen’s The Sympathizer Amanda R. Gradisek iet Nguyen’s The Sympathizer has a problem with women but it is a problem that the novel carefully and even deliberately confronts. While the novel could be read V as the story of the aftermath of the Vietnam War, the essentially fragmenting and divisive process of assimilation, or even the implications of American imperial power globally, I read it through the lens of gender, considering the ways in which the physical bodies of women set the stage and even reframe the narrative for all of these readings. Because women’s bodies are often implicated in struggles for power, they become, in this novel, the sites upon and through which male characters act out and process their desires for power and belonging. Because I read the novel as a feminist woman who lives in the world, I react to it viscerally as a woman; I cannot help but do so. As Sarah Ahmed writes in her book Living A Feminist Life, a feminist has a “sensible reaction to the injustices of the world, which we must register at first through our own experiences” (21). In order to “make sense of what does not make sense,” I read through what Ahmed calls my own “feminist story” to personalize the disembodied, critical reading of texts. In a similar way, this novel is in some ways about the narrator’s reformulation of his own story as he learns to view it in a new way. While the main character of the novel is a man, the women of the novel refract his understanding of self, and even when he struggles to look directly at their inherently sexualized, often obscene treatment, Nguyen’s relentless return to women’s sexualized bodies provides the narrator a lens by which to reenvision his own doubled identity and complex story.