Two Readings of Two Books by Viet Thanh Nguyen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Reading 2021

Shady Side Academy Senior School Summer Reading 2021 This summer, you will have the opportunity to read two (2) books before returning to classes in the fall. You will read one book to be discussed in your Fall term English class, and one to be discussed with your Advisory group. English Book: See the list below for your Form’s text. You should be prepared to discuss it in your English class, so be sure to read and annotate it in such a way that you have some knowledge of it in your working memory when you are back on campus; your fall-term English teacher will give you more details about what you will do with that knowledge when you meet him/her on the first day of classes. Above all, enjoy the reading! Advisory Book: All Form III students will read the same book; students in Forms IV, V, and VI can find their texts listed below under their individual advisor’s name. You should plan on being prepared to discuss this book with your advisory group during an extended Designated Rooms meeting during the first week of classes. Your advisor may also ask you to write up something on your text in preparation for that discussion session, perhaps in a Google document of some kind; stay tuned for details when the opening of classes draws nearer. In the meantime, please enjoy the selection your advisor has made. View the Table of Contents on the next page to see the assigned books per form and per advisory. If you are purchasing books locally, please consider supporting the following independent bookstores: City of Asylum Bookstore, Riverstone Books, -

Download Spring 2015

LAUREN ACAMPORA CHARLES BRACELEN FLOOD JOHN LeFEVRE BELINDA BAUER ROBERT GODDARD DONNA LEON MARK BILLINGHAM FRANCISCO GOLDMAN VAL McDERMID BEN BLATT & LEE HALL with TERRENCE McNALLY ERIC BREWSTER TOM STOPPARD & ELIZABETH MITCHELL MARK BOWDEN MARC NORMAN VIET THANH NGUYEN CHRISTOPHER BROOKMYRE WILL HARLAN JOYCE CAROL OATES MALCOLM BROOKS MO HAYDER P. J. O’ROURKE KEN BRUEN SUE HENRY DAVID PAYNE TIM BUTCHER MARY-BETH HUGHES LACHLAN SMITH ANEESH CHOPRA STEVE KETTMANN MARK HASKELL SMITH BRYAN DENSON LILY KING ANDY WARHOL J. P. DONLEAVY JAMES HOWARD KUNSTLER KENT WASCOM GWEN EDELMAN ALICE LaPLANTE JOSH WEIL MIKE LAWSON Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, 12 FL, New York, New York 10011 GROVE PRESS Hardcovers APRIL A startling debut novel from a powerful new voice featuring one of the most remarkable narrators of recent fiction: a conflicted subversive and idealist working as a double agent in the aftermath of the Vietnam War The Sympathizer Viet Thanh Nguyen MARKETING Nguyen is an award-winning short story “Magisterial. A disturbing, fascinating and darkly comic take on the fall of writer—his story “The Other Woman” Saigon and its aftermath and a powerful examination of guilt and betrayal. The won the 2007 Gulf Coast Barthelme Prize Sympathizer is destined to become a classic and redefine the way we think about for Short Prose the Vietnam War and what it means to win and to lose.” —T. C. Boyle Nguyen is codirector of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network and edits a profound, startling, and beautifully crafted debut novel, The Sympathizer blog on Vietnamese arts and culture is the story of a man of two minds, someone whose political beliefs Published to coincide with the fortieth A clash with his individual loyalties. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Dayton Literary Peace Prize

BRAILLE AND TALKING BOOK LIBRARY (800) 952-5666; btbl.ca.gov; [email protected] Award Winners: Dayton Literary Peace Prize The Dayton Literary Peace Prize is an international award that recognizes fiction and nonfiction books that promote peace and lead to a better understanding of diversity. It has been awarded annually since 2006. The winners are listed chronologically with the most recent award recipient first. Not all winners are available through the library at this time. To order any of these titles, contact the library by email, phone, mail, in person, or order through our online catalog. Most titles can be downloaded from BARD. 2019 Winner Rising Out of Hatred: the Awakening of a Former White Nationalist by Eli Saslow Read by Eli Saslow and Scott Brick 9 hours, 4 minutes A Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter recounts the trajectory of white nationalist Derek Black’s enlightenment and change of heart after he left home to attend college. When Black’s beliefs were exposed on campus, an Orthodox Jew began meeting with him, prompting Black to question his worldview. Some violence, strong language. Commercial audiobook. 2018. Download from BARD: Rising Out of Hatred: the Awakening of a… Also available on digital cartridge DB092497 2018 Winners Salt Houses by Hala Alyan Read by Leila Buck 12 hours, 17 minutes Salma reads her daughter Alia’s future in the dregs of Alia’s coffee cup. It’s a future filled with unsettling events, travel, and luck. The family is uprooted from Palestine and scattered in the wake of the Six-Day War in 1967. -

Wayne Karlin

Writing the War Wayne Karlin Kissing the Dead …I have thumped and blown into your kind too often, I grow tired of kissing the dead. —Basil T. Paquet’s (former Army medic) “Morning, a Death” in Winning Hearts and Minds: War Poems by Vietnam Veterans n November 2017, the old war intruded again onto America’s consciousness, at least that portion of the population that still watches PBS and whose conception of an even older I war was informed by the soft Southern drawl of Shelby Foote, sepia images of Yankees and Confederates, and the violin lamentations of Ashokan Farewell, all collaged by Ken Burns in his 1990 landmark documentary about the Civil War. Burns’ and Lynn Novick’s new series on the Vietnam War evoked arguments among everyone I knew who watched it; their reactions to it were like conceptions of the war itself: the nine blind Indians touching different parts of the elephant, assuming each was the whole animal. Three words tended to capture my own reaction to the series: “the Walking Dead,” a phrase that these days connotes a TV show about zombies but was the name given to what we Marines call One-Nine, meaning the First Battalion of the Ninth Marines, meaning the ungodly number of Marines killed in action from that battalion, which fought, as one of its former members interviewed by Burns and Novick recalled, along the ironically-named Demilitarized Zone, the DMZ. The Dead Marine Zone, as the veteran interviewed more accurately called it, and what I saw after I watched his segment was the dead I’d seen piled on the deck of the CH-46 War, Literature & the Arts: an international journal of the humanities / Volume 31 / 2019 I flew in as a helicopter gunner during operations in that area. -

RHO Readers Literary Journey

RHO* Readers Literary Journey October 2020 The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien September 2020 The Bookwoman of Troublesome Creek by Kim Michelle Richardson August 2020 The Secrets We Kept by Lara Prescott July 2020 Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America by Jonathan M. Metzl June 2020 The Dutch House by Ann Patchett May 2020 The Suspect: An Olympic Bombing, the FBI, the Media, and Richard Jewell, The Man Caught in the Middle by Alexander Kent April 2020 City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert March 2020 (No meeting) February 2020 A Well-Behaved Woman: A Novel of the Vanderbilts by Therese Anne Fowler January 2020 The Secret Diary of Hendrik Groen by Hendrik Groen, 83 ¼ Yrs. Old November 2019 The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary by Simon Winchester October 2019 The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead September 2019 Metropolis by Philip Kerr August 2019 On the Porch, Under the Eave by Jane Simpson July 2019 Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens June 2019 Washington Black by Esi Edugyan May 2019 Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America by Beth Macy April 2019 Unsheltered: A Novel by Barbara Kingsolver March 2019 Macbeth / William Shakespeare's Macbeth Retold: A Novel by Jo Nesbo February 2019 Educated: A Memoir by Tara Westover January 2019 Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart November 2018 Whiskey When We're Dry by John Larsen October 2018 The Death of Democracy: Hitler’s Rise to Power and the Downfall of the Weimar -

The Impact of Trauma on Vietnamese Refugees in Robert Olen Butler's a Good Scent from a Strange Mountain (1992) and Viet Thanh

مجلة كلية اﻵداب للغويات والثقافات المقارنة مج 12، ع1 )يناير(2020 The Impact of Trauma on Vietnamese Refugees in Robert Olen Butler’s A Good Scent from A Strange Mountain (1992) and Viet Thanh Nguyen The Refugees (2017) By Dr. Sherine Abdelghafar [email protected] ABSTRACT After the collapse of the South Vietnamese government, thousands of people fled away from their own country. Eventually, by the late 1980s and early 1990s, many individuals made their way to the United States in order to escape intolerable conditions in their countries and to seek a better life. There were three waves of Vietnamese immigration; the most significant and complicated was the third wave, which came after 1982; it included different types of Vietnamese refugees. This paper attempts to study the challenges Vietnamese refugees have faced in the U.S. Selected stories from the collections of A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain (1992) by Robert Olen Butler, and The Refugees (2017) by Viet Thanh Nguyen, will be studied in the light of the refugee trauma theory. The Vietnam War was a unique war in history and, thus, called for an equally distinctive representation in literature. The stories, in both collections, are connected by the common experience of characters that have survived the war in Vietnam and found their way to America. Both writers offer a diverse group of characters—some protagonists are Vietnamese, others are American, but most are Vietnamese-American. Through the different stories of their characters, Butler and Nguyen explore questions of identity. They focus on how it feels and what it means to be a refugee. -

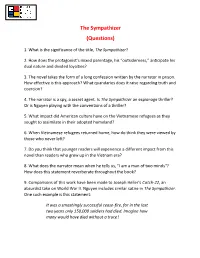

The Sympathizer (Questions)

The Sympathizer (Questions) 1. What is the significance of the title, The Sympathizer? 2. How does the protagonist’s mixed parentage, his “outsiderness,” anticipate his dual nature and divided loyalties? 3. The novel takes the form of a long confession written by the narrator in prison. How effective is this approach? What quandaries does it raise regarding truth and coercion? 4. The narrator is a spy, a secret agent. Is The Sympathizer an espionage thriller? Or is Nguyen playing with the conventions of a thriller? 5. What impact did American culture have on the Vietnamese refugees as they sought to assimilate in their adopted homeland? 6. When Vietnamese refugees returned home, how do think they were viewed by those who never left? 7. Do you think that younger readers will experience a different impact from this novel than readers who grew up in the Vietnam era? 8. What does the narrator mean when he tells us, "I am a man of two minds"? How does this statement reverberate throughout the book? 9. Comparisons of this work have been made to Joseph Heller's Catch-22, an absurdist take on World War II. Nguyen includes similar satire in The Sympathizer. One such example is this statement: It was a smashingly successful cease-fire, for in the last two years only 150,000 soldiers had died. Imagine how many would have died without a truce! Can you find other examples where the author employs similar satiric wit? What affect does such a stylistic device have on your reading? Does the black humor lessen the horror of the war, or draw more attention to it? 10. -

English (ADEN)-126601 – Contemporary American Ethnic

English (ADEN)-126601 – Contemporary American Ethnic Literature (4 credits) Woods College of Advancing Studies Fall 2017 Semester, August 28 – Dec 16, 2017 Tuesdays 6:15-9:15pm Instructor Name: AKLUA SARR BC E-mail: [email protected] Phone Number: 617-552-9144 Office: Waul House 202 Office Hours: By Appointment Only Boston College Mission Statement Strengthened by more than a century and a half of dedication to academic excellence, Boston College commits itself to the highest standards of teaching and research in undergraduate, graduate and professional programs and to the pursuit of a just society through its own accomplishments, the work of its faculty and staff, and the achievements of its graduates. It seeks both to advance its place among the nation's finest universities and to bring to the company of its distinguished peers and to contemporary society the richness of the Catholic intellectual ideal of a mutually illuminating relationship between religious faith and free intellectual inquiry. Boston College draws inspiration for its academic societal mission from its distinctive religious tradition. As a Catholic and Jesuit university, it is rooted in a world view that encounters God in all creation and through all human activity, especially in the search for truth in every discipline, in the desire to learn, and in the call to live justly together. In this spirit, the University regards the contribution of different religious traditions and value systems as essential to the fullness of its intellectual life and to the continuous development of its distinctive intellectual heritage. Course Description Ethnic difference has a profound effect on personal and social understandings of what it means to be an American. -

GMLC Kitkeeper Book Set List Audience Genre Title Author Copies Owning Library

GMLC KitKeeper Book Set List Audience Genre Title Author Copies Owning Library Adult Biography An American childhood Dillard, Annie 8 Burnham Adult Biography Becoming Obama, Michelle 10 Milton Adult Biography Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood Noah, Trevor 10 South Burlington Kimmerer, Robin Adult Biography Braiding sweetgrass 9 Fletcher Free Wall Adult Biography Calypso Sedaris, David 10 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Can't we talk about something more pleasant? [graphic novel] Chast, Roz 8 Fletcher Free Adult Biography The dawn watch : Joseph Conrad in a global war Jasanoff, Maya 8 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Dora Bruder Modiano, Patrick 5 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Educated : a memoir Westover, Tara Fletcher Free Adult Biography Educated : a memoir Westover, Tara 8 Burnham Adult Biography Endurance : a year in space, a lifetime of discovery Kelly, Scott 10 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Hidden figures Lee Shetterly, Margot 10 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Hillbilly Elegy Vance, J.D. 9 South Burlington Adult Biography Hillbilly Elegy Vance, J.D. 10 Fletcher Free Adult Biography I saw Ramallah Barghuthi, Murid 5 Fletcher Free 1 GMLC KitKeeper Book Set List Nelson, Jessica Adult Biography If only you people could follow directions : a memoir 5 Fletcher Free Hendry Adult Biography In a sunburned country Bryson, Bill 5 Fletcher Free In the garden of beasts : love, terror, and an American family Adult Biography Larson, Erik 5 Fletcher Free in Hitler's Berlin Adult Biography Just kids Smith, Patti 10 Fletcher Free Adult Biography Just mercy : a story of justice and redemption Stevenson, Bryan Fletcher Free Adult Biography March: Book One Lewis, John 10 South Burlington Adult Biography Reading Lolita in Tehran : a memoir in books Nafisi, Azar 5 Fletcher Free Boylan, Jennifer Adult Biography She's not there : a life in two genders 9 Fletcher Free Finney Adult Biography The short and tragic life of Robert Peace Hobbs, Jeff 10 Fletcher Free Those turbulent sons of freedom : Ethan Allen's Green Adult Biography Wren, Christopher S. -

SYMPATHIZER-Catalog-Pages.Pdf

APRIL A startling debut novel from a powerful new voice featuring one of the most remarkable narrators of recent fiction: a conflicted subversive and idealist working as a double agent in the aftermath of the Vietnam War The Sympathizer Viet Thanh Nguyen MARKETING Nguyen is an award-winning short story “Magisterial. A disturbing, fascinating and darkly comic take on the fall of writer—his story “The Other Woman” Saigon and its aftermath and a powerful examination of guilt and betrayal. The won the 2007 Gulf Coast Barthelme Prize Sympathizer is destined to become a classic and redefine the way we think about for Short Prose the Vietnam War and what it means to win and to lose.” —T. C. Boyle Nguyen is codirector of the Diasporic profound, startling, and beautifully crafted debut novel, The Sympathizer Vietnamese Artists Network and edits a is the story of a man of two minds, someone whose political beliefs blog on Vietnamese arts and culture clash with his individual loyalties. In dialogue with but diametrically Published to coincide with the fortieth A opposed to the narratives of the Vietnam War that have preceded it, this novel anniversary of the Fall of Saigon offers an important and unfamiliar new perspective on the war: that of a con- prepublication reading copies flicted communist sympathizer. eGalleys available on NetGalley and Edelweiss It is April 1975, and Saigon is in chaos. At his villa, a general of the South 8-city tour (Boston * New York City * Vietnamese army is drinking whiskey and, with the help of his trusted captain, Washington, D.C.