The Impact of Trauma on Vietnamese Refugees in Robert Olen Butler's a Good Scent from a Strange Mountain (1992) and Viet Thanh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Spring 2015

LAUREN ACAMPORA CHARLES BRACELEN FLOOD JOHN LeFEVRE BELINDA BAUER ROBERT GODDARD DONNA LEON MARK BILLINGHAM FRANCISCO GOLDMAN VAL McDERMID BEN BLATT & LEE HALL with TERRENCE McNALLY ERIC BREWSTER TOM STOPPARD & ELIZABETH MITCHELL MARK BOWDEN MARC NORMAN VIET THANH NGUYEN CHRISTOPHER BROOKMYRE WILL HARLAN JOYCE CAROL OATES MALCOLM BROOKS MO HAYDER P. J. O’ROURKE KEN BRUEN SUE HENRY DAVID PAYNE TIM BUTCHER MARY-BETH HUGHES LACHLAN SMITH ANEESH CHOPRA STEVE KETTMANN MARK HASKELL SMITH BRYAN DENSON LILY KING ANDY WARHOL J. P. DONLEAVY JAMES HOWARD KUNSTLER KENT WASCOM GWEN EDELMAN ALICE LaPLANTE JOSH WEIL MIKE LAWSON Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, 12 FL, New York, New York 10011 GROVE PRESS Hardcovers APRIL A startling debut novel from a powerful new voice featuring one of the most remarkable narrators of recent fiction: a conflicted subversive and idealist working as a double agent in the aftermath of the Vietnam War The Sympathizer Viet Thanh Nguyen MARKETING Nguyen is an award-winning short story “Magisterial. A disturbing, fascinating and darkly comic take on the fall of writer—his story “The Other Woman” Saigon and its aftermath and a powerful examination of guilt and betrayal. The won the 2007 Gulf Coast Barthelme Prize Sympathizer is destined to become a classic and redefine the way we think about for Short Prose the Vietnam War and what it means to win and to lose.” —T. C. Boyle Nguyen is codirector of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network and edits a profound, startling, and beautifully crafted debut novel, The Sympathizer blog on Vietnamese arts and culture is the story of a man of two minds, someone whose political beliefs Published to coincide with the fortieth A clash with his individual loyalties. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

DESPERATION ROAD MICHAEL FARRIS SMITH MARKETING & SALES POINTS Longlisted for the CWA Gold Dagger 2017

DESPERATION ROAD MICHAEL FARRIS SMITH MARKETING & SALES POINTS Longlisted for the CWA Gold Dagger 2017 'Every once in a while an author comes along who's in love with art and written language and imagery... writers like William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy and Annie Proulx. You can add Michael Farris Smith's name to the list' - James Lee Burke For fans of Cormac McCarthy, Daniel Woodrell and Annie Proulx Michael Farris Smith's previous novel, Rivers, won the 2014 Mississippi Authors Award for Fiction and was named a Best Book of 2013 by Esquire, Daily Candy, BookRiot, and Hudson Booksellers THE BOOK In the vein of Daniel Woodrell's Winter's Bone and the works of Ron Rash, a novel set in a rough- and-tumble Mississippi town where drugs, whiskey, guns, and the desire for revenge violently intersect For eleven years the clock has been ticking for Russell Gaines as he sat in Parchman penitentiary in the Download high resolution image Mississippi Delta. His time now up, and believing his debt paid, he returns home only to discover that Pub. Date: 23 February 2017 revenge lives and breathes all around. Price: £14.99 ISBN: 978-1-84344-987-4 On the day of his release, a woman named Maben and her young daughter trudge along the side of the Binding: Hardback interstate under the punishing summer sun. Desperate and exhausted, the pair spend their last dollar on Format: Royal (234 x 153mm) a motel room for the night, a night that ends with Maben running through the darkness holding a pistol, Extent: 288 and a dead deputy sprawled across the road in the glow of his own headlights. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Classical Goddesses in American Short Fiction

CLASSICAL GODDESSES IN AMERICAN SHORT FICTION ABOUT THE VIETNAM WAR by ANDREA DEAN FONTENOT, B.S., M.F.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approv94? August, 1998 Ac cop' '^ Copyright 1998 by Andrea Dean Fontenot ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. Wendell Aycock for his support, patience, and guidance during the preparation for this work. I want to extend my appreciation to Dr. Bryce Conrad and Dr. Michael Schoenecke who, along with Dr. Aycock, allowed me the opportunity to explore a subject that interests me and who gave me insightflil and conscientious direction during the revision process. I want to extend my gratitude to Dr. William Marcy, Dean of the College of Engineering, for allowing me to take much needed time away from my position in order to complete this degree, and for the unending support that he and the College of Engineering have extended to me. I want to thank John Chandler for his support. Finally, I want to thank my family, especially my mother Ruby McDowell for always reminding me that it is never too late to learn and never too late to accomplish seemingly impossible tasks. And I want to especially thank Ron Fontenot for his many years of support and encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1 n PERSEPHONE: THE MAIDEN AND INNOCENCE 29 m DEMETER: THE MOTHER AND EXPERIENCE 64 IV HECATE: THE WISE CRONE AND RECONSTRUCTION 99 V. -

Dayton Literary Peace Prize

BRAILLE AND TALKING BOOK LIBRARY (800) 952-5666; btbl.ca.gov; [email protected] Award Winners: Dayton Literary Peace Prize The Dayton Literary Peace Prize is an international award that recognizes fiction and nonfiction books that promote peace and lead to a better understanding of diversity. It has been awarded annually since 2006. The winners are listed chronologically with the most recent award recipient first. Not all winners are available through the library at this time. To order any of these titles, contact the library by email, phone, mail, in person, or order through our online catalog. Most titles can be downloaded from BARD. 2019 Winner Rising Out of Hatred: the Awakening of a Former White Nationalist by Eli Saslow Read by Eli Saslow and Scott Brick 9 hours, 4 minutes A Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter recounts the trajectory of white nationalist Derek Black’s enlightenment and change of heart after he left home to attend college. When Black’s beliefs were exposed on campus, an Orthodox Jew began meeting with him, prompting Black to question his worldview. Some violence, strong language. Commercial audiobook. 2018. Download from BARD: Rising Out of Hatred: the Awakening of a… Also available on digital cartridge DB092497 2018 Winners Salt Houses by Hala Alyan Read by Leila Buck 12 hours, 17 minutes Salma reads her daughter Alia’s future in the dregs of Alia’s coffee cup. It’s a future filled with unsettling events, travel, and luck. The family is uprooted from Palestine and scattered in the wake of the Six-Day War in 1967. -

Draft Syllabi Are Provided to Assist Students in the Course Registration Process

Please Note: Draft syllabi are provided to assist students in the course registration process. Final syllabi will be provided by instructors. Wesleyan University, Graduate Liberal Studies HUMS622: Writing and Revision Brando Skyhorse Tuesdays and Thursdays, 6:30pm-9:30pm June 26-August1; No Class July 4 Course Description Revision is considered the final stage of writing but what is it, exactly? What does the process entail? What constitutes a revision? How do other writers revise? And what are the rules writers can follow to make revision a cornerstone of their writing process? You’ll find out in this class. Revision, simply, is not correction. Revision is not changing “red” to “crimson” or running your spell checker. Revision is a change in your point-of-view. This class’s goal is to help you learn how to change your point-of-view. Through a series of writing exercises, classroom discussions, and applying a specific checklist of revision oriented questions, the goal is to help you understand how revision works, and how you can develop your own revision process to apply to both fiction and non-fiction writing. This is a graduate level writing course. We’ll be focusing on short stories and personal essays but the bulk of our course will be based on a short story of fiction OR a non-fiction essay that you write and revise over the course of a semester. Think of our five week, ten session class as an arc of a story. YOUR story. In the first week you’ll write the first draft of a short story or personal essay. -

Wayne Karlin

Writing the War Wayne Karlin Kissing the Dead …I have thumped and blown into your kind too often, I grow tired of kissing the dead. —Basil T. Paquet’s (former Army medic) “Morning, a Death” in Winning Hearts and Minds: War Poems by Vietnam Veterans n November 2017, the old war intruded again onto America’s consciousness, at least that portion of the population that still watches PBS and whose conception of an even older I war was informed by the soft Southern drawl of Shelby Foote, sepia images of Yankees and Confederates, and the violin lamentations of Ashokan Farewell, all collaged by Ken Burns in his 1990 landmark documentary about the Civil War. Burns’ and Lynn Novick’s new series on the Vietnam War evoked arguments among everyone I knew who watched it; their reactions to it were like conceptions of the war itself: the nine blind Indians touching different parts of the elephant, assuming each was the whole animal. Three words tended to capture my own reaction to the series: “the Walking Dead,” a phrase that these days connotes a TV show about zombies but was the name given to what we Marines call One-Nine, meaning the First Battalion of the Ninth Marines, meaning the ungodly number of Marines killed in action from that battalion, which fought, as one of its former members interviewed by Burns and Novick recalled, along the ironically-named Demilitarized Zone, the DMZ. The Dead Marine Zone, as the veteran interviewed more accurately called it, and what I saw after I watched his segment was the dead I’d seen piled on the deck of the CH-46 War, Literature & the Arts: an international journal of the humanities / Volume 31 / 2019 I flew in as a helicopter gunner during operations in that area. -

RHO Readers Literary Journey

RHO* Readers Literary Journey October 2020 The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien September 2020 The Bookwoman of Troublesome Creek by Kim Michelle Richardson August 2020 The Secrets We Kept by Lara Prescott July 2020 Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America by Jonathan M. Metzl June 2020 The Dutch House by Ann Patchett May 2020 The Suspect: An Olympic Bombing, the FBI, the Media, and Richard Jewell, The Man Caught in the Middle by Alexander Kent April 2020 City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert March 2020 (No meeting) February 2020 A Well-Behaved Woman: A Novel of the Vanderbilts by Therese Anne Fowler January 2020 The Secret Diary of Hendrik Groen by Hendrik Groen, 83 ¼ Yrs. Old November 2019 The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary by Simon Winchester October 2019 The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead September 2019 Metropolis by Philip Kerr August 2019 On the Porch, Under the Eave by Jane Simpson July 2019 Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens June 2019 Washington Black by Esi Edugyan May 2019 Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America by Beth Macy April 2019 Unsheltered: A Novel by Barbara Kingsolver March 2019 Macbeth / William Shakespeare's Macbeth Retold: A Novel by Jo Nesbo February 2019 Educated: A Memoir by Tara Westover January 2019 Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart November 2018 Whiskey When We're Dry by John Larsen October 2018 The Death of Democracy: Hitler’s Rise to Power and the Downfall of the Weimar -

Pulitzer Prize

1946: no award given 1945: A Bell for Adano by John Hersey 1944: Journey in the Dark by Martin Flavin 1943: Dragon's Teeth by Upton Sinclair Pulitzer 1942: In This Our Life by Ellen Glasgow 1941: no award given 1940: The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck 1939: The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Prize-Winning 1938: The Late George Apley by John Phillips Marquand 1937: Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell 1936: Honey in the Horn by Harold L. Davis Fiction 1935: Now in November by Josephine Winslow Johnson 1934: Lamb in His Bosom by Caroline Miller 1933: The Store by Thomas Sigismund Stribling 1932: The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1931 : Years of Grace by Margaret Ayer Barnes 1930: Laughing Boy by Oliver La Farge 1929: Scarlet Sister Mary by Julia Peterkin 1928: The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder 1927: Early Autumn by Louis Bromfield 1926: Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis (declined prize) 1925: So Big! by Edna Ferber 1924: The Able McLaughlins by Margaret Wilson 1923: One of Ours by Willa Cather 1922: Alice Adams by Booth Tarkington 1921: The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton 1920: no award given 1919: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington 1918: His Family by Ernest Poole Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue Deer Park, NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 2012: no award given 1980: The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer 2011: Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 1979: The Stories of John Cheever by John Cheever 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding 1978: Elbow Room by James Alan McPherson 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 1977: No award given 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 1976: Humboldt's Gift by Saul Bellow 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 1975: The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 1974: No award given 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 1973: The Optimist's Daughter by Eudora Welty 2004: The Known World by Edward P. -

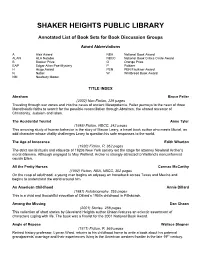

An Annotated Listing of Book Sets

SHAKER HEIGHTS PUBLIC LIBRARY Annotated List of Book Sets for Book Discussion Groups Award Abbreviations A Alex Award NBA National Book Award ALAN ALA Notable NBCC National Book Critics Circle Award B Booker Prize O Orange Prize EAP Edgar Allan Poe-Mystery P Pulitzer H Hugo Award PEN PEN/Faulkner Award N Nobel W Whitbread Book Award NM Newbery Medal TITLE INDEX Abraham Bruce Feiler (2002) Non-Fiction, 229 pages Traveling through war zones and into the caves of ancient Mesopotamia, Feiler journeys to the heart of three Monotheistic faiths to search for the possible reconciliation through Abraham, the shared ancestor of Christianity, Judaism and Islam. The Accidental Tourist Anne Tyler (1985) Fiction, NBCC, 342 pages This amusing study of human behavior is the story of Macon Leary, a travel book author who meets Muriel, an odd character whose vitality challenges Leary to question his safe responses to the world. The Age of Innocence Edith Wharton (1920) Fiction, P, 362 pages The strict social rituals and etiquette of 1920s New York society set the stage for attorney Newland Archer’s moral dilemma. Although engaged to May Welland, Archer is strongly attracted to Welland’s nonconformist cousin Ellen. All the Pretty Horses Cormac McCarthy (1992) Fiction, NBA, NBCC, 302 pages On the cusp of adulthood, a young man begins an odyssey on horseback across Texas and Mexico and begins to understand the world around him. An American Childhood Annie Dillard (1987) Autobiography, 255 pages This is a vivid and thoughtful evocation of Dillard’s 1950s childhood in Pittsburgh. Among the Missing Dan Chaon (2001) Stories, 258 pages This collection of short stories by Cleveland Heights author Chaon features an eclectic assortment of characters coping with life. -

AUTUMN 2013 2 0 1 3 • 1 a Career and a Passion the Writing Life of Adam Johnson, FSU Alumnus and Winner of the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

Across the AUTUMN THETHE FLORIDA FLORIDA STATE STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE COLLEGE OF OF ARTS ARTS AND AND SCIENCES SCIENCES 2 0 1 3 Spectrum New Frontiers Pushing boundaries—on campus and around the world artsandsciences.fsu.edu AUTUMN 2 0 1 3 • 1 Letter from the dean elcome to another edition of Across the Spectrum. As the fall 2013 academic year kicked off, the College of Arts Sciences found itself serving record numbers of students. At the same time there was a welcome expansion in the faculty ranks, owing to the hiring of 25 new faculty members. In this issue, we celebrate our college’s growth, not only in size, but in the depth and breadth of our research, our educational offerings, and our global Photo by FSU Photo Lab Photo FSU by Photo W impact. DEAN PUBLISHER Several of our new faculty hires will spend time at the MagLab, which has become a crown jewel for FSU Sam Huckaba Nancy Smilowitz over the last 20 years. In this issue you will read about its history and get a sense of why scientists flock to EDITOR DESIGNER Tallahassee from all over the world to do research that literally cannot be done anywhere else. Physicist and Wil Oakes Martin Young MagLab director Greg Boebinger explains why magnetic field environments are so important to modern www.oakescreative.com [email protected] research projects ranging from materials science to medicine. PHOTOGRAPHY COPY EDITOR One great benefit of having the MagLab at FSU is that it attracts world-class faculty members—such as Tamara Beckwith Barry Ray Alan Marshall Lawton Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Alan Marshall.