Relationship Between Social Support Status and Mortality in a Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Dewa Sanzan? the Spiritual Awe-Inspiring Mountains in the Tohoku Area, Embracing Peopleʼs Prayers… from the Heian Period, Mt.Gassan, Mt.Yudono and Mt

The ancient road of Dewa Rokujurigoegoe Kaido Visit the 1200 year old ancient route! Sea of Japan Yamagata Prefecture Tsuruoka City Rokujurigoe Kaido Nishikawa Town Asahi Tourism Bureau 60-ri Goe Kaido Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture The Ancient Road “Rokujuri-goe Kaido” Over 1200 years, this road has preserved traces of historical events “Rokujuri-goe Kaido,” an ancient road connecting the Shonai plain and the inland area is said to have opened about 1200 years ago. This road was the only road between Shonai and the inland area. It was a precipitous mountain road from Tsuruoka city to Yamagata city passing over Matsune, Juo-toge, Oami, Sainokami-toge, Tamugimata and Oguki-toge, then going through Shizu, Hondoji and Sagae. It is said to have existed already in ancient times, but it is not clear when this road was opened. The oldest theory says that this road was opened as a governmental road connecting the Dewa Kokufu government which was located in Fujishima town (now Tsuruoka city) and the county offices of the Mogami and Okitama areas. But there are many other theories as well. In the Muromachi and Edo periods, which were a time of prosperity for mountain worship, it became a lively road with pilgrims not only from the local area,but also from the Tohoku Part of a list of famous places in Shonai second district during the latter half of the Edo period. and Kanto areas heading to Mt. Yudono as “Oyama mairi” (mountain pilgrimage) custom was (Stored at the Native district museum of Tsuruoka city) booming. -

Business Operation Plan for Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2010

Business Operation Plan for Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2010 February 27, 2009 Nippon Telegraph and Telephone East Corporation (“NTT East”) 1. Revenue and Expenses Plan (Unit: billions of yen) Item FY 3/10 FY 3/09 Change Operating Revenues 1,930 1,960 (30) Voice Transmission* (excluding IP-Related services) 820 910 (90) IP-Related* 660 575 85 Leased Circuits* (excluding IP- Related services) 160 171 (11) Operating Expenses 1,890 1,920 (30) Personnel* 114 115 (1) Non-Personnel* 1,245 1,280 (35) Depreciation, Amortization and Other* 531 525 6 Operating Income 40 40 0 Non-Operating Revenues 20 30 (10) Recurring Profits 60 70 (10) *Major items Note: Figures for FY 3/09 have changed since the results for the six months ended September 30, 2008 were announced. The figures announced for that period were 900 billion yen for voice transmission services (excluding IP-Related services) and 590 billion yen for IP-Related revenues. 1 2. Trends in Operating Income and Changes in Earnings Structure (Unit: Billions of yen) FY 3/07 FY 3/08 FY 3/09 Forecasts FY 3/10 Plan 59.9 Operating Income (14.9) 44.9 Operating Revenues 40.0 40.0 2,061.3 (4.9) ±0.0 (58.6) 2,002.7 (42.7) IP 1,960.0 (30.0) 1,930.0 359.4 +103.2 [17.4%] IP 462.6 Voice transmissions+IP +112.4 [23.1%] IP 1,518.5 IP (23.8) 575.0 +85.0 Voice transmissions +IP [29.3%] 660.0 1,494.6 [34.2%] (9.5) Voice transmissions +IP 1,485.0 (5.0) Voice transmissions +IP 1,480.0 Voice Transmissions 1,159.0 (127.0) Voice Transmissions 1,031.9 (121.9) Voice Transmissions 910.0 Voice Transmissions (90.0) 820.0 Other Other Other 542.8 Other 508.0 475.0 450.0 Note: Numbers in brackets indicate composition ratios of operating revenues 2 3. -

Digidepo 1164546 Po Nourinsu

The Report of the Study on the Protection of Cultural Landscapes Associated with Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Table of Contents Introduction 1 1. Background and Purpose of the Study 2 (1) Background 2 A. Academic Research on“Cultural Landscapes”in Japan 3 B. International Trend regarding“Cultural Landscapes”………………………………………… 4 (a)“Cultural Lanscapes”in the World Heritage Convention 4 Cultural Landscapes in the World Heritage Convention Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras Increasing Number of Inscriptions of“Cultural Landscapes”on the World Heritage List and Future Challenges (b) Protection of“Cultural Landscapes”in Other International Agreements 10 C. Rise in the Public Demand for the Protection of“Cultural Landscape”in Japan 10 (a) Reports of the National Council, etc. 11 Cultural Promotion Master Plan (Basic Plan) Reprort of the Cultural Properties Working Group of the Council for Cultural Affairs (b) Progress of Agricultural Land Conservation and Improvement Projects in Semi-Mountainous Regions 12 (c) Environmental Conservation in the Ancient Cities Preservation Law 13 (d) Promotion of“Cultural Landscapes”in Landscape Ordinances 14 D. Designation of“Cultural Landscapes”as Places of Scenic Beauty 17 (a)“Obasute (Tagoto no Tsuki)”…………………………………………………………… 17 (b)“Shiroyone no Semmaida”……………………………………………………………… 20 (2) Purpose and Methodology 21 2. History and Development of Study 21 (1) Definition of“Cultural Landscape” …………………………………………………………… 22 (2) 1st Phase Study and 2nd Phase Study …………………………………………………………… 22 (3) Categorization -

「Pre-Games Training Camp Facilities」 (Acceptable Only)

PyeongChang 2018 Olympic and Paralympic Games 「Pre-games Training Camp Facilities」 (Acceptable Only) TOHOKU / JAPAN No time difference Training Camps in KOREA PyeongChang 2018 TOHOKU ECONOMIC FEDERATION / JAPAN (February 2017 Edition) Convenient Railway & Airline in Tohoku Aomori → Seoul About 3 hours (By a direct flight) Aomori Prefecture Morioka PyeongChang → Aomori About 2018 Akita Prefecture Iwate Prefecture 50 minutes (By Shinkansen) Sendai → Seoul About 2.5 hours (By a direct flight) Sendai → Morioka About 40 minutes Miyagi Prefecture Niigata → Seoul Yamagata Prefecture (By Shinkansen) About 2.5 hours (By a direct flight) Niigata Prefecture Fukushima Prefecture Tokyo Tokyo → Sendai → Niigata About About 90 minutes 90 minutes Shinkansen (By Shinkansen) Tokyo → Seoul About 2.5 hours (By a direct flight) 2 / 19 Contents ・Alpine Skiing .................................. 4 ・Cross-country Skiing ...................... 7 ・Ski Jumping .................................... 9 ・Nordic Combined ...........................10 ・Freestyle Skiing ..............................11 ・Snowboard .....................................12 ・Speed Skating .................................14 ・Figure Skating .................................15 ・Short Track Speed Skating ..............16 ・Ice Hockey ......................................17 ・Curling ............................................18 ・Biathlon ..........................................19 「Pre-games Training Camp Facilities (Acceptable Only)」 TOHOKU / JAPAN Alpine Skiing You can see more detail information -

33. Zaozan (Zaosan))

(33. Zaozan (Zaosan)) 33. Zaozan (Zaosan) Continuously Monitored by JMA Latitude: 38°08'37" N, Longitude: 140°26'24" E, Elevation: 1,841 m (Kumanodake) (GSI Measuring Point) Overview of Zaozan (Zaosan). Taken from Zao Town on November 27, 2011 by the Japan Meteorological Agency. Summary Zaozan (Zaosan) is a basalt-andesite stratovolcano group, of which volcanic activity started with subaqueous eruption of the basaltic magma approximately 1 million to 700 thousand years ago. It was dormant for roughly 300,000 years, and then approximately 400,000 to 100,000 years ago many andesitic lava flows were discharged from multiple eruption centers, forming the peaks which make up the upper half of the volcanic edifice, such as Kumanodake (the highest peak) and Kattadake, forming the basic structure of the volcano. Approximately 30,000 years ago a caldera roughly 2 km in diameter was formed at the summit. At the same time, explosive activity involving basaltic andesite magma began, continuing intermittently even until today. Goshikidake is a post-caldera pyroclastic cone (or tuff cone) which formed within the caldera above. It has been active since approximately 2,000 years ago, and is the site of Okama crater lake (360 m in diameter, also known as Goshikinuma). Many records exist of eruptions at Okama within history. The eruptions which caused damage occurred at both inside and outside of Okama. Many of these eruptions were accompanied by lahars. Fumaroles are located in several areas, such as the new fumaroles to the northeast of Okama. The SiO2 content is between 51.3 and 64.1 wt %. -

![Download Paper [PDF:2.0MB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3161/download-paper-pdf-2-0mb-4433161.webp)

Download Paper [PDF:2.0MB]

DPRIETI Discussion Paper Series 11-E-068 Do More Productive Firms Locate New Factories in More Productive Locations? An empirical analysis based on panel data from Japan's Census of Manufactures FUKAO Kyoji RIETI IKEUCHI Kenta NISTEP KIM YoungGak Senshu University KWON Hyeog Ug RIETI The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry http://www.rieti.go.jp/en/ RIETI Discussion Paper Series 11-E-068 September 2011 Do More Productive Firms Locate New Factories in More Productive Locations? An empirical analysis based on panel data from Japan’s Census of Manufactures FUKAO Kyoji (Hitotsubashi University, RIETI) IKEUCHI Kenta (NISTEP) KIM YoungGak (Senshu University) KWON Hyeog Ug (Nihon University, RIETI) Abstract Using a Melitz-style model of heterogeneous firms, Baldwin and Okubo (2006) recently presented a theoretical model in which self-sorting occurs and more productive factories choose to locate in more productive areas. The model suggests that firm-specific factors and regional factors affect each other through the endogeneity of location decisions. However, to date there have been few studies empirically testing this issue. Against this background, our aim is to examine the relationship between firms and location-specific factors in location decisions using factory-level panel data from Japan’s Census of Manufactures. We begin by estimating how much of the differences in factories’ TFP levels can be explained by both firm and location effects. The estimation results show that both effects have a significant impact on the productivity level of a factory, and that the firm effects are more important than the location effects. We also find a statistically significant negative correlation between firm effects and location effects, and investigate what causes this relationship. -

The Benibana Museum

The Benibana Museum The Safflower Museum YAMAGATA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Copyrightⓒ Kahoku Town 2006 First published in 2007 by Yamagata University Library. Yamagata University Library 1-4-12 Kojirakawa-machi Yamagata Japan 990-8560 http://www.lib.yamagata-u.ac.jp/ This pamphlet is a translation of “The Benebana Musesum” published by Kahoku Town in 1994. English translation was prepared by Masanobu Hayakawa, Emertius Professor, Yamagata University. The publisher has permission to translate and publish from copyright owner. - 1 - CONTENTS 1. Benibana (Safflower : Carthamus Tinctorius) Revived 3 2. From the Horigome Residence of a Wealthy Farmer to the Museum 3 3. Horigome’s Former Residence 6 4. The Benibana House 10 5. Place of Origin of Benibana 16 6. Flora of Benibana 17 7. Kinds of Benibana 17 8. Its Use and Effect 18 9. How to Grow Benibana 18 10. Variety of Dyeing Materials 19 11. Main Plants Dyes 19 12. Technique of Benibana Dyes 20 13. Benibana Dyeing for Everybody 20 14. How to Make Benibana Wine 21 15. How to Make Rouge 21 16. History of Benibana 23 17. Benibana Charmed the Noblemen 23 18. Benibana for Tax Obligation 24 19. Nobunaga Oda Made a Present of Benibana 24 20. Supplication of Yoshiaki Mogami 25 21. Anrakuji Temple Documents of Benibana Donation 25 22. Evaluation of Mogami Benibana 26 23. Prosperity of Flower Market 26 24. “Mebaya” and “Sanbe” as Traders 27 25. All the Fields Covered with Benibana 27 26. Two Haiku Lines of Benibana 28 27. Yield of Benibana 28 28. Area under Cultivation of Mogami-benibana 29 29. -

Handbook for KCCP for JICA Scholarship Courses

Handbook for Knowledge Co-Creation Program (Long Term) Handbook for Knowledge Co-Creation Program for All JICA Scholarship Courses September, 2019 Japan International Cooperation Agency, JICA Name of JICA Scholarship Courses SDGs Global Leadership Program Enhancement of Administrative Capacity Master‘s Degree and Internship Program of African Business Education Initiative for Youth(ABE Initiative) Project for Human Resources Development of in Public Administration for Sustainable Development Road Asset Management Advanced Training Program for Fostering Global Leaders on Infectious Disease Control to Build Resilience against Public Health Emergencies Disaster and Radiation Medical Science Program for Improvement in Children’s Learning JICA Long-term Training Program for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) to implement the Sendai Framework Water Engineering and Utility Management Future Leaders Training Program JICA Long-term Training Program on the Forest Governance Initiative Agriculture Studies Networks for Food Security (Agri-Net) Hydrogen Energy Human Resources Development in the Mining Sector (KIZUNA Program) Development of Core Human Resource in Agricultural Sector (phase 2) The Project for Future Researchers at IITH to Enhance Network Development with Scholarship of Japan The Project for Strengthening the Capacity of Research Activities of Uzbek-Japan Innovation Center of Youth Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................... 1 1-1. People and Organizations -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials Contents Data S1 Initial survey questionnaire ............................................................................ 1 Data S2 Second phase questionnaire ........................................................................... 2 Data S3 Complete list of Northern Japanese fire departments to which the questionnaire was sent ...................................................................................................................... 4 Table S1 Characteristics of responding Northern Japanese fire departments (n = 140) ........................................................................................................................... 8 Figure S1 Perceived importance of endotracheal intubation (ETI) for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) patients and video laryngoscope education among Northern Japanese emergency life-saving technicians (ELSTs). ............................................ 9 Table S2 Correlations between confidence in performing ETI, confidence in other airway management skills, anxiety about ETI experience, and anxiety about skill retention . 10 Table S3 Sensitivity analysis: multivariable models of factors associated with endotracheal intubation confidence among Northern Japanese emergency life-saving technicians ................................................................................................................ 11 Data S1 Initial survey questionnaire Survey of airway management for advanced-level emergency life-saving technicians (Initial survey questionnaire) -

Dam/Barrage Year /Anne E River /Riviere City/Ville St/Et/ Pr/Dpt Type

Year Found Hight Vol Area Length Catc SpillCap/ River St/Et/ Type Leng Purp Type Sp Dam/barrage /Anne City/Ville /Fondatio /Haut /Vol Capacit. /Sur /Long /Bvers. E Owner/Proprie Engine/Bur.d'et Contractor/Entr /Riviere Pr/Dpt /Type /Long m /Buts /Typ Eva e n en m 103m3 103m2 km Km2 m3/s ICHIBANIKE 400 Ishite Matsuyama Ehime TE R 15 180 50 140 I 0 N Higashino Irrigation Assoc. Kagoshim Mitsumata Land SUMIYOSHIIKE 400 Beppu Gamo a TE R 20 60 14 230 I 0 N Improvement Assoc. KAERUMATAIKE 607 Yodo Nara Nara TE R 17 260 159 485 I 0 N Nara City SAYAMAIKE 616 Yamato Tondabayashi Osaka TE R 19 997 605 2800 I 18 0 N Osaka Prefecture (Obayashi-Gumi Co.) FUROTANIIKE 900 Kino Hashimoto Wakayam TE R 18 100 26 100 I 0 N Furotaniike Irrigation Wakayam Kumamichiike Irrigation KUMAMICHIIKE 900 Kino Hashimoto a TE R 18 32 5 9 I 0 N Assoc. MINENOIKE 900 Kino Hashimoto Wakayam TE R 16 45 7 15 I 0 N Minenoike Irrigation Assoc. Shido Land Improvement NAGAYUKIIKE 1000 Ohashi Takamatsu Kagawa TE R 20 171 87 483 I 0 N Assoc. Tatsuno Land DAIMONIKE 1128 Daimon Nara Nara TE X 20 78 105 98 10 I 0 N Improvement Assoc. SHINTARO 1260 Hido Ueno Mie TE 19 150 73 35 I Private Dam MARUYAMA(YAMAGU Yamaguch Maruyama Users'. CHI) 1346 Ara Ube i TE R 18 46 24 120 I 0 N Ube City Group OIKE 1360 Kino Hashimoto Wakayam TE R 18 80 30 200 I 0 N Oike Irrigation Assoc. -

Wine, Beer, Whisky, Etc

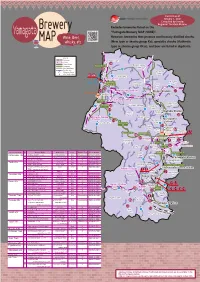

Current as of January 1, 2021 Compiled by Sendai Regional Taxation Bureau Brewery Excludes breweries listed on the Yamagata "Yamagata Brewery MAP (SAKE)". Wine, Beer, However, breweries that produce continuously distilled shochu MAP whisky, etc. (New type or shochu group Ko), specialty shochu (Authentic type or shochu group Otsu), and beer are listed in duplicate. Legend Shinkansen Yuza Town JR Line Private Railway Mamurogawa Expressway Yuzahiko IC Major National Highway Town 344 City Boundary Shinkansen Station Kaneyama JR and Private Railway Stations Town 345 Uetsu Main Line Sakata City Sakata Station Sakata Port 112 Sakegawa Mogami Shinjo Town Village 47 City Rikuu east Line Amarume Station Shinjo Station Shonai Airport Mikawa Town 47 Rikuu West Line Tsuruoka Station Obanazawa 7 Tozawa Village Funagata City 458 Town Oishida Oishida Station Shonai Town 112 Uetsu Main Line Town 13 Atsumi-Onsen Okura Village Murayama Station Murayama 347 Station 345 Tsuruoka City City Sagae Sakurambo- City Higashine Kahoku Station Town Yamagata Higashine Airport 48 City Sagae Station Aterazawa Tendo Station Station Tendo Nishikawa City e n Lin Town Senza Nakayama Yamadera Station Oe Town Town Aterazawa Line Uzen- Chitose Station Kita- Name of City, Town, and Village No. Brewery Name Brand Name Genre Brewery Tour Phone Number Yamagata Asahi Station 286 Kaminoyama City ① TAKEDA WINERY Co.,Ltd. TAKEDA WINERY Wine ○Reservation 023-672-0040 Town Yamanobe ② Zao Woody Farm Ltd. Woody Farm & winery Wine ○Reservation 023-674-2343 Town Yamagata Station 287 ③ BELLWOOD VINEYARD Collection Classique Wine × 023-674-6020 Yamagata City Tendo City ④ TENDO BREWERY SOBA DRY Beer × 023-654-3311 348 ⑤ TENDO WINE CO.,LTD TENDO WINE Wine ○Reservation 023-655-5151 Shirataka Town SANWA CANNIG Company Limited. -

Club Health Assessment MBR0087

Club Health Assessment for District 332 E through July 2020 Status Membership Reports Finance LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Activity Account Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Report *** Balance Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater report in 3 more than of officers thatin 12 months within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not haveappears in two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active red Clubs more than two years old P,T,M,VP,MC 25447 AMARUME 04/16/1967 Active 16 0 1 -1 -5.88% 17 9 0 N 24+ SC Exc Award (06/30/2018) P,S,T,M,VP 31385 FUJISHIMA 11/24/1975 Active 49 1 0 1 2.08% 51 0 N 24+ MC,SC Exc Award (06/30/2016, 06/30/2018, 06/30/2019) S,T,M,VP,MC 30793 HAGURO 05/12/1975 Active 16 1 0 1 6.67% 21 0 2 N 24+ SC Exc Award (06/30/2016, 06/30/2018) P,S,T,M,VP 25456 HIGASHINE 12/14/1969 Active 14 0 0 0 0.00% 21 1 1 None 24+ MC,SC P,S,T,M,VP 62394 HIGASHINE SAKURANBO 09/29/1999 Active 46 0 0 0 0.00% 48 0 1 None 24+ MC,SC Exc Award (06/30/2016, 06/30/2018) P,S,T,M,VP 42139 IIDE 12/13/1982 Active 26 2 2 0 0.00% 23 16 0 24+ MC,SC Exc Award (06/30/2016, 06/30/2017, 06/30/2019) T,M,VP,MC,SC 25466 KAHOKU 04/19/1964 Active 37 0 0 0 0.00% 38 0 N 1 Exc Award (06/30/2016)