Download Paper [PDF:2.0MB]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hyōgo Prefecture

Coor din ates: 3 4 °4 1 ′2 6 .9 4 ″N 1 3 5 °1 0′5 9 .08″E Hyōgo Prefecture Hyōgo Prefecture (兵庫県 Hyōgo-ken) is a prefecture of Japan located in the Kansai region on Hyōgo Prefecture Honshu island.[1] The capital is Kobe.[2] 兵庫県 Prefecture Contents Japanese transcription(s) • Japanese 兵庫県 History • Rōmaji Hyōgo-ken Geography Cities Towns Islands National parks Mergers Flag Future mergers Symbol Economy Culture National Treasures of Japan Important Preservation Districts for Groups of Historic Buildings in Japan Museums Education Universities Amagasaki Takarazuka Sanda Nishinomiya Ashiya Kobe Kato Akashi Kakogawa Country Japan Himeji Region Kansai Akō Island Honshu High schools Capital Kobe Sports Government Tourism • Governor Toshizō Ido Festival and events Area Transportation Rail • Total 8,396.13 km2 People movers (3,241.76 sq mi) Road Area rank 12th Expressways Population (November 1, 2011) National highways Ports • Total 5,582,978 Airport • Rank 7th • Density 660/km2 (1,700/sq mi) Notable people Sister regions ISO 3166 JP-28 code See also Notes Districts 8 References Municipalities 41 External links Flower Nojigiku (Chrysanthemum japonense) Tree Camphor tree History (Cinnamomum camphora) Bird Oriental white stork Present-day Hyōgo Prefecture includes the former provinces of Harima, Tajima, Awaji, and parts (Ciconia boyciana) of Tanba and Settsu.[3] Website web.pref.hyogo.lg.jp/fl /english/ (http://web.pre In 1180, near the end of the Heian period, Emperor Antoku, Taira no Kiyomori, and the Imperial f.hyogo.lg.jp/fl/english/) court moved briefly to Fukuhara, in what is now the city of Kobe. -

Studies on the Genesis of Metallic Mineral Deposits of Shin Jo and Yamagata Basins, Northeastern Japan (I)

岩 石鉱 物鉱 床学 会誌 60巻4号, 1968年 STUDIES ON THE GENESIS OF METALLIC MINERAL DEPOSITS OF SHIN JO AND YAMAGATA BASINS, NORTHEASTERN JAPAN (I) NORITSUGU OIZUMI Mining Division Prefectuval Governient of Yamagata The present structural set up of the Shinjo and Yamagata basins which are situated within the Inner Region, Northeastern Japan, is a result of repeated uplift and submergence coupled with igneous activity and sedimentation during the early stage of the Neogene. Those structur es formed as a result of uplift of the basement are the major faults and fissures parallel to the N-S trend of the present axis of the Basement Rise and the subordinate faults and fissures trending E-W and perpen dicular to that axis Those formed as a result of folding of the sedimentary rocks are the NNW-SSE trending structures of northern Shinjo Basin, the N-S trending structures of southern Shinjo Basin, the N-S trending structures of northern Yamagata Basin, and the NNE-SSW trending structures of southern Yamagata Basin. These structures include the fold axes and the faults and fissures parallel to them. In addition to these structures produced by folding of the sedimentary rocks, are the subordinate faults and fissures trending WNW and NE-SW to ENE. The crushed zones within these fractures were produced by an E-W lateral compression, which also produced exceedingly abundant E-W trending tension fractures, The NNE-SSE trending fissures adhere closely to these fractures caused by lateral compression. The individual ore deposits present within the two basins amount to a total of more than 300 ore deposits. -

Supplementary Chapter: Technical Notes

Supplementary Chapter: Technical Notes Tomoki Nakaya, Keisuke Fukui, and Kazumasa Hanaoka This supplementary provides the details of several advanced principle, tends to be statistically unstable when ei is methods and analytical procedures used for the atlas project. small. Bayesian hierarchical modelling with spatially structured random effects provides flexible inference frameworks to T1 Spatial Smoothing for Small-Area-Based obtain statistically stable and spatially smoothed estimates of Disease Mapping: BYM Model and Its the area-specific relative risk. The most popular model is the Implementation BYM model after the three authors who originally proposed it, Besag, York, and Mollié (Besag et al. 1991). The model T. Nakaya without covariates is shown as: oe|θθ~Poisson Disease mapping using small areas such as municipalities in ii ()ii this atlas often suffers from the problem of small numbers. log()θα=+vu+ In the case of mapping SMRs, small numbers of deaths in a iii spatial unit cause unstable SMRs and make it difficult to where α is a constant representing the overall risk, and vi and read meaningful geographic patterns over the map of SMRs. ui are unstructured and spatially structured random effects, To overcome this problem, spatial smoothing using statisti- respectively. The unstructured random effect is a simple cal modelling is a common practice in spatial white noise representing the geographically independent epidemiology. fluctuation of the relative risk: When we can consider the events of deaths to occur inde- vN~.0,σ 2 pendently with a small probability, it is reasonable to assume iv() the following Poisson process: The spatially structured random effect models the spatial correlation of the area-specific relative risks among neigh- oe|θθ~Poisson ii ()ii bouring areas: where oi and ei are the observed and expected numbers of wu deaths in area i, and is the relative risk of death in area i. -

Nagano Regional

JTB-Affiliated Ryokan & Hotels Federation Focusing mainly on Nagano Prefecture Regional Map Nagano Prefecture, where the 1998 winter Olympics were held, is located in the center of Japan. It is connected to Tokyo in the southeast, Nagoya in the southwest, and also to Kyoto and Osaka. To the northeast you can get to Niigata, and to the northwest, you can get to Toyama and Kanazawa. It is extremely convenient to get to any major region of Japan by railroad, or highway bus. From here, you can visit all of the major sightseeing area, and enjoy your visit to Japan. Getting to Nagano Kanazawa Toyama JR Hokuriku Shinkansen Hakuba Iiyama JR Oito Line JR Hokuriku Line Nagano Ueda Karuizawa Limited Express () THUNDER BIRD JR Shinonoi Line JR Hokuriku Matsumoto Chino JR Chuo Line Shinkansen JR Chuo Line Shinjuku Shin-Osaka Kyoto Nagoya Tokyo Narita JR Tokaido Shinkansen O 二ニ〕 kansai Chubu Haneda On-line゜ Booking Hotel/Ryokan & Tour with information in Japan CLICK! CLICK! ~ ●JAPAN iCAN.com SUN 廊 E TOURS 四 ※All photos are images. ※The information in this pamphlet is current as of February 2019. ≫ JTB-Affiliated Ryokan & Hotels Federation ヽ ACCESS NAGANO ヽ Narita International Airport Osaka Haneda(Tokyo ダ(Kansai International International Airport) Airport) Nagoya Snow Monkey (Chubu Centrair The wild monkeys who seem to International Airport) enjoy bathing in the hot springs during the snowy season are enormously popular. Yamanouchi Town, Nagano Prefecture Kenrokuen This Japanese-style garden is Sado ga shima Niigata (Niigata Airport) a representative example of Nikko the Edo Period, with its beauty Niigata This dazzling shrine enshrines and grandeur. -

Effects of Viewing Forest Landscape on Middle-Aged Hypertensive Men

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 21 (2017) 247–252 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Urban Forestry & Urban Greening journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ufug Original article Effects of viewing forest landscape on middle-aged hypertensive men a,1 a,1,2 b c b Chorong Song , Harumi Ikei , Maiko Kobayashi , Takashi Miura , Qing Li , d e f a,∗ Takahide Kagawa , Shigeyoshi Kumeda , Michiko Imai , Yoshifumi Miyazaki a Center for Environment, Health and Field Sciences, Chiba University, 6-2-1 Kashiwa-no-ha, Kashiwa, Chiba 277-0882, Japan b Department of Hygiene and Public Health, Nippon Medical School, 1-1-5 Sendagi, Bunkyo-Ku, Tokyo 113-8602, Japan c Agematsu Town Office, Industry & Tourism Department, 159-3 Agematsu, Kiso, Nagano 399-5601, Japan d Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, 1 Matsunosato, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8687, Japan e Nagano Prefectural Kiso Hospital, 6613-4 Kisomachi-fukushima, Nagano 397-8555, Japan f Le Verseau Inc., 3-19-4 Miyasaka, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 156-0051, Japan a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: With increasing attention on the health benefits of a forest environment, evidence-based research is Received 13 June 2016 required. This study aims to provide scientific evidence concerning the physiological and psychological Received in revised form 6 December 2016 effects of exposure to the forest environment on middle-aged hypertensive men. Twenty participants Accepted 18 December 2016 (58.0 ± 10.6 years) were instructed to sit on chairs and view the landscapes of forest and urban (as control) Available online 28 December 2016 environments for 10 min. -

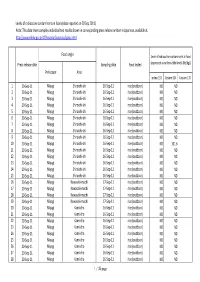

This Data Sheet Compiles Individual Test Results Shown in Corresponding

Levels of radioactive contaminants in foods (data reported on 20 Sep 2011) Note: This data sheet compiles individual test results shown in corresponding press release written in Japanese, available at http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/bukyoku/iyaku.html Food origin Level of radioactive contaminants in food Press release date Sampling date Food tested (expressed as radionuclide levels (Bq/kg)). Prefecture Area Iodine‐131 Cesium‐134 Cesium‐137 1 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 2 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 3 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 4 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 5 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 6 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 7 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 8 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 9 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 10 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND 101.6 11 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 12 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 13 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 14 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 15 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Shiroishi‐shi 16‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 16 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Kawasaki‐machi 17‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 17 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi Kawasaki‐machi 17‐Sep‐11 rice (outdoor) ND ND 18 20‐Sep‐11 Miyagi -

LIST of the WOOD PACKAGING MATERIAL PRODUCER for EXPORT 2007/2/10 Registration Number Registered Facility Address Phone

LIST OF THE WOOD PACKAGING MATERIAL PRODUCER FOR EXPORT 2007/2/10 Registration number Registered Facility Address Phone 0001002 ITOS CORPORATION KAMOME-JIGYOSHO 62-1 KAMOME-CHO NAKA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-622-1421 ASAGAMI CORPORATION YOKOHAMA BRANCH YAMASHITA 0001004 279-10 YAMASHITA-CHO NAKA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-651-2196 OFFICE 0001007 SEITARO ARAI & CO., LTD. TORIHAMA WAREHOUSE 12-57 TORIHAMA-CHO KANAZAWA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-774-6600 0001008 ISHIKAWA CO., LTD. YOKOHAMA FACTORY 18-24 DAIKOKU-CHO TSURUMI-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-521-6171 0001010 ISHIWATA SHOTEN CO., LTD. 4-13-2 MATSUKAGE-CHO NAKA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-641-5626 THE IZUMI EXPRESS CO., LTD. TOKYO BRANCH, PACKING 0001011 8 DAIKOKU-FUTO TSURUMI-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-504-9431 CENTER C/O KOUEI-SAGYO HONMOKUEIGYOUSHO, 3-1 HONMOKU-FUTO NAKA-KU 0001012 INAGAKI CO., LTD. HONMOKU B-2 CFS 045-260-1160 YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 0001013 INOUE MOKUZAI CO., LTD. 895-3 SYAKE EBINA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 046-236-6512 0001015 UTOC CORPORATION T-1 OFFICE 15 DAIKOKU-FUTO TSURUMI-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-501-8379 0001016 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU B-1 OFFICE B-1, HONMOKU-FUTOU, NAKA-KU, YOKOHAMA-SHI, KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-621-5781 0001017 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU D-5 CFS 1-16, HONMOKU-FUTOU, NAKA-KU, YOKOHAMA-SHI, KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-623-1241 0001018 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU B-3 OFFICE B-3, HONMOKU-FUTOU, NAKA-KU, YOKOHAMA-SHI, KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-621-6226 0001020 A.B. SHOUKAI CO., LTD. -

Tokuyama Dam

Day Driving 1 to Dams & Canals No.1 Western Mino Route toward Japan’s No.1 Tokuyama Dam Japan with a long history and tradition has varieties of diversied cultures. And each locality has it own distinc- 終点 Final Destination tive features that attract visitors. Sight-seeing spots, a local delicacy, a joyful event, etc. are all dierent by Tokuyama Dam locality. The areas where dams or canals of Japan Water 徳山ダム Agency are located have many attractions. ● 徳山会館 With this project of introduction of attractive touring Tokuyama Hall destinations , we would like to present you some of the Fujihashi Castle & distinctive features of the locality . Why don’t you rent a Nishimino Astronomial 藤橋城 car at a major railway station of the locality and get Observatory (西美濃プラネタリウム) (Nisimino Planetarium) started for your trip, stopping by at some of the attrac- 5 tive spots on the way to the nal destination of the dam 417 or the canal of Japan Water Agency. Oku-Ibi Bridge カーブが連続、 注意 奥いび湖大橋 A series of bends The rst trip is “Western Mino Route toward Tokuyama Dam, No,1 water storage dam in Japan.” 303 ● 道の駅 星ふる里ふじはし 至 木之本 Road Station For Kinomoto 横山ダム Yokoyama Starry Place Fujihashi Dam 303 417 Kegonji (Tanigumisan) 谷汲山華厳寺 ● Ibi Town Hall Narrow road width 揖斐川町役場 Miwa Shrine Watch out 幅員狭し、注意 Haginaga ●三輪神社 Bridge ● 脛永橋 Ono Town Hall Unique spot 4 大野町役場 ● 揖斐駅 157 Mt. Ibuki ●かすがモリモリ村 Ibi Station 伊吹山 リフレッシュ館 Yoro 3 303 Kasuga Morimori Village Railways 養老鉄道 Refleshing Hall 揖 斐 川 Ibi River Ogaki Station Enbankment堤 road 防 Enlarged 大垣駅 道 路 至 岐阜 view 拡大図 417 For -

What Is Dewa Sanzan? the Spiritual Awe-Inspiring Mountains in the Tohoku Area, Embracing Peopleʼs Prayers… from the Heian Period, Mt.Gassan, Mt.Yudono and Mt

The ancient road of Dewa Rokujurigoegoe Kaido Visit the 1200 year old ancient route! Sea of Japan Yamagata Prefecture Tsuruoka City Rokujurigoe Kaido Nishikawa Town Asahi Tourism Bureau 60-ri Goe Kaido Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture The Ancient Road “Rokujuri-goe Kaido” Over 1200 years, this road has preserved traces of historical events “Rokujuri-goe Kaido,” an ancient road connecting the Shonai plain and the inland area is said to have opened about 1200 years ago. This road was the only road between Shonai and the inland area. It was a precipitous mountain road from Tsuruoka city to Yamagata city passing over Matsune, Juo-toge, Oami, Sainokami-toge, Tamugimata and Oguki-toge, then going through Shizu, Hondoji and Sagae. It is said to have existed already in ancient times, but it is not clear when this road was opened. The oldest theory says that this road was opened as a governmental road connecting the Dewa Kokufu government which was located in Fujishima town (now Tsuruoka city) and the county offices of the Mogami and Okitama areas. But there are many other theories as well. In the Muromachi and Edo periods, which were a time of prosperity for mountain worship, it became a lively road with pilgrims not only from the local area,but also from the Tohoku Part of a list of famous places in Shonai second district during the latter half of the Edo period. and Kanto areas heading to Mt. Yudono as “Oyama mairi” (mountain pilgrimage) custom was (Stored at the Native district museum of Tsuruoka city) booming. -

Regional Map Nagano Prefecture, Where the 1998 Winter Olympics Were Held, Is Located in the Center of Japan

JTB-Affiliated Ryokan & Hotels Federation Focusing mainly on Nagano Prefecture Regional Map Nagano Prefecture, where the 1998 winter Olympics were held, is located in the center of Japan. It is connected to Tokyo in the southeast, Nagoya in the southwest, and also to Kyoto and Osaka. To the northeast you can get to Niigata, and to the northwest, you can get to Toyama and Kanazawa. It is extremely convenient to get to any major region of Japan by railroad, or highway bus. From here, you can visit all of the major sightseeing area, and enjoy your visit to Japan. Getting to Nagano Kanazawa Toyama JR Hokuriku Shinkansen Hakuba Iiyama JR Oito Line JR Hokuriku Line Nagano Ueda Karuizawa Limited Express ( THUNDER BIRD) JR Shinonoi Line JR Hokuriku Matsumoto Chino JR Chuo Line Shinkansen JR Chuo Line Shinjuku Shin-Osaka Kyoto Nagoya Tokyo Narita JR Tokaido Shinkansen kansai Chubu Haneda On-line Booking Hotel/Ryokan & Tour with information in Japan CLICK! CLICK! ※All photos are images. ※The information in this pamphlet is current as of February 2019. JTB-Affiliated Ryokan & Hotels Federation ACCESS NAGANO Narita International Airport Osaka Haneda(Tokyo (Kansai International International Airport) Airport) Nagoya Snow Monkey (Chubu Centrair The wild monkeys who seem to International Airport) enjoy bathing in the hot springs during the snowy season are enormously popular. Yamanouchi Town, Nagano Prefecture Kenrokuen This Japanese-style garden is Sado ga shima Niigata (Niigata Airport) a representative example of Nikko the Edo Period, with its beauty Niigata This dazzling shrine enshrines and grandeur. It is considered Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first one of the three best gardens Hokuriku Shogun who began the Edo in Japan. -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13 -

Business Operation Plan for Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2010

Business Operation Plan for Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2010 February 27, 2009 Nippon Telegraph and Telephone East Corporation (“NTT East”) 1. Revenue and Expenses Plan (Unit: billions of yen) Item FY 3/10 FY 3/09 Change Operating Revenues 1,930 1,960 (30) Voice Transmission* (excluding IP-Related services) 820 910 (90) IP-Related* 660 575 85 Leased Circuits* (excluding IP- Related services) 160 171 (11) Operating Expenses 1,890 1,920 (30) Personnel* 114 115 (1) Non-Personnel* 1,245 1,280 (35) Depreciation, Amortization and Other* 531 525 6 Operating Income 40 40 0 Non-Operating Revenues 20 30 (10) Recurring Profits 60 70 (10) *Major items Note: Figures for FY 3/09 have changed since the results for the six months ended September 30, 2008 were announced. The figures announced for that period were 900 billion yen for voice transmission services (excluding IP-Related services) and 590 billion yen for IP-Related revenues. 1 2. Trends in Operating Income and Changes in Earnings Structure (Unit: Billions of yen) FY 3/07 FY 3/08 FY 3/09 Forecasts FY 3/10 Plan 59.9 Operating Income (14.9) 44.9 Operating Revenues 40.0 40.0 2,061.3 (4.9) ±0.0 (58.6) 2,002.7 (42.7) IP 1,960.0 (30.0) 1,930.0 359.4 +103.2 [17.4%] IP 462.6 Voice transmissions+IP +112.4 [23.1%] IP 1,518.5 IP (23.8) 575.0 +85.0 Voice transmissions +IP [29.3%] 660.0 1,494.6 [34.2%] (9.5) Voice transmissions +IP 1,485.0 (5.0) Voice transmissions +IP 1,480.0 Voice Transmissions 1,159.0 (127.0) Voice Transmissions 1,031.9 (121.9) Voice Transmissions 910.0 Voice Transmissions (90.0) 820.0 Other Other Other 542.8 Other 508.0 475.0 450.0 Note: Numbers in brackets indicate composition ratios of operating revenues 2 3.