11 Setting and Organization of the General Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alameda, a Geographical History, by Imelda Merlin

Alameda A Geographical History by Imelda Merlin Friends of the Alameda Free Library Alameda Museum Alameda, California 1 Copyright, 1977 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 77-73071 Cover picture: Fernside Oaks, Cohen Estate, ca. 1900. 2 FOREWORD My initial purpose in writing this book was to satisfy a partial requirement for a Master’s Degree in Geography from the University of California in Berkeley. But, fortunate is the student who enjoys the subject of his research. This slim volume is essentially the original manuscript, except for minor changes in the interest of greater accuracy, which was approved in 1964 by Drs. James Parsons, Gunther Barth and the late Carl Sauer. That it is being published now, perhaps as a response to a new awareness of and interest in our past, is due to the efforts of the “Friends of the Alameda Free Library” who have made a project of getting my thesis into print. I wish to thank the members of this organization and all others, whose continued interest and perseverance have made this publication possible. Imelda Merlin April, 1977 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to acknowledge her indebtedness to the many individuals and institutions who gave substantial assistance in assembling much of the material treated in this thesis. Particular thanks are due to Dr. Clarence J. Glacken for suggesting the topic. The writer also greatly appreciates the interest and support rendered by the staff of the Alameda Free Library, especially Mrs. Hendrine Kleinjan, reference librarian, and Mrs. Myrtle Richards, curator of the Alameda Historical Society. The Engineers’ and other departments at the Alameda City Hall supplied valuable maps an information on the historical development of the city. -

List of AOIME Institutions

List of AOIME Institutions CEEB School City State Zip Code 1001510 Calgary Olympic Math School Calgary AB T2X2E5 1001804 ICUC Academy Calgary AB T3A3W2 820138 Renert School Calgary AB T3R0K4 820225 Western Canada High School Calgary AB T2S0B5 996056 WESTMOUNT CHARTER SCHOOL CALGARY AB T2N 4Y3 820388 Old Scona Academic Edmonton AB T6E 2H5 C10384 University of Alberta Edmonton AB T6G 2R3 1001184 Vernon Barford School Edmonton AB T6J 2C1 10326 ALABAMA SCHOOL OF FINE ARTS BIRMINGHAM AL 35203-2203 10335 ALTAMONT SCHOOL BIRMINGHAM AL 35222-4445 C12963 University of Alabama at Birmingham Birmingham AL 35294 10328 Hoover High School Hoover AL 35244 11697 BOB JONES HIGH SCHOOL MADISON AL 35758-8737 11701 James Clemens High School Madison AL 35756 11793 ALABAMA SCHOOL OF MATH/SCIENCE MOBILE AL 36604-2519 11896 Loveless Academic Magnet Program High School Montgomery AL 36111 11440 Indian Springs School Pelham AL 35124 996060 LOUIS PIZITZ MS VESTAVIA HILLS AL 35216 12768 VESTAVIA HILLS HS VESTAVIA HILLS AL 35216-3314 C07813 University of Arkansas - Fayetteville Fayetteville AR 72701 41148 ASMSA Hot Springs AR 71901 41422 Central High School Little Rock AR 72202 30072 BASIS Chandler Chandler AZ 85248-4598 30045 CHANDLER HIGH SCHOOL CHANDLER AZ 85225-4578 30711 ERIE SCHOOL CAMPUS CHANDLER AZ 85224-4316 30062 Hamilton High School Chandler AZ 85248 997449 GCA - Gilbert Classical Academy Gilbert AZ 85234 30157 MESQUITE HS GILBERT AZ 85233-6506 30668 Perry High School Gilbert AZ 85297 30153 Mountain Ridge High School Glendale AZ 85310 30750 BASIS Mesa -

Alameda Unified School District Is Very Highly Rated, and Is Ranked in in the Top 70 School Districts in the US's Largest State

ABOUT THE District Alameda Unified School District is very highly rated, and is ranked in in the top 70 school districts in the US's largest state. The district offers an abundance of diverse courses, clubs, and athletic programs to help Facilities students feel a sense of belonging and pride for their Alameda High School, one of the two high schools school. Alameda has a high standard for academic in the district, is located in a historic building achievement, with graduates attending top schools (above), that was recently restored. Both Alameda across the US. and Encinal High Schools have great athletic and academic facilities. alameda unified school district Alameda, California QUICK Facts: # of Students: 1700 Graduation Offered: Yes Teacher:Student Ratio: 1:23 # of High Schools in District: 2 Is ESL Offered: Yes Nearest Airport: Oakland Estimated Start Date: Late Aug. Fall Semester Program: No International Airport Estimated End Date: Mid June Spring Semester Program: No Airport Code: OAK COURSES OFFERED Math Algebra I-II, Advanced Algebra II, Geometry, Pre-Calculus, Calculus (AP), Statistics (AP) EXTRACURRICULAR ACTIVITIES Science Biology (AP), Principles of Chemistry & ATHLETICS SCHOOL CLUBS Biotechnology, Chemistry (AP), AP Environmental BOYS Science, Physics (AP), Physiology • Business/ Fall Football, Cross Country, Cheerleading, Water Polo, Entrepreneurship Club • Computer Science Club Social Studies • Creative Writing Circle Modern World History, AP European History, Winter Basketball, Soccer, • Disney Club Cheerleading US History -

National Blue Ribbon Schools Recognized 1982-2015

NATIONAL BLUE RIBBON SCHOOLS PROGRAM Schools Recognized 1982 Through 2015 School Name City Year ALABAMA Academy for Academics and Arts Huntsville 87-88 Anna F. Booth Elementary School Irvington 2010 Auburn Early Education Center Auburn 98-99 Barkley Bridge Elementary School Hartselle 2011 Bear Exploration Center for Mathematics, Science Montgomery 2015 and Technology School Beverlye Magnet School Dothan 2014 Bob Jones High School Madison 92-93 Brewbaker Technology Magnet High School Montgomery 2009 Brookwood Forest Elementary School Birmingham 98-99 Buckhorn High School New Market 01-02 Bush Middle School Birmingham 83-84 C.F. Vigor High School Prichard 83-84 Cahaba Heights Community School Birmingham 85-86 Calcedeaver Elementary School Mount Vernon 2006 Cherokee Bend Elementary School Mountain Brook 2009 Clark-Shaw Magnet School Mobile 2015 Corpus Christi School Mobile 89-90 Crestline Elementary School Mountain Brook 01-02, 2015 Daphne High School Daphne 2012 Demopolis High School Demopolis 2008 East Highland Middle School Sylacauga 84-85 Edgewood Elementary School Homewood 91-92 Elvin Hill Elementary School Columbiana 87-88 Enterprise High School Enterprise 83-84 EPIC Elementary School Birmingham 93-94 Eura Brown Elementary School Gadsden 91-92 Forest Avenue Academic Magnet Elementary School Montgomery 2007 Forest Hills School Florence 2012 Fruithurst Elementary School Fruithurst 2010 George Hall Elementary School Mobile 96-97 George Hall Elementary School Mobile 2008 1 of 216 School Name City Year Grantswood Community School Irondale 91-92 Guntersville Elementary School Guntersville 98-99 Heard Magnet School Dothan 2014 Hewitt-Trussville High School Trussville 92-93 Holtville High School Deatsville 2013 Holy Spirit Regional Catholic School Huntsville 2013 Homewood High School Homewood 83-84 Homewood Middle School Homewood 83-84, 96-97 Indian Valley Elementary School Sylacauga 89-90 Inverness Elementary School Birmingham 96-97 Ira F. -

Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines, 1985. Ranked Magazines. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 265 562 CS 209 541 AUTHOR Gibbs, Sandra E., Comp. TITLE Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines, 1985. Ranked Magazines. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, PUB DATE Mar 86 NOTE 88p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - General (130) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Awards; Creative Writing; Evaluation Criteria; Layout (Publications); Periodicals; Secondary Education; *Student Publications; Writing Evaluation IDENTIFIERS Contests; Excellence in Education; *Literary Magazines; National Council of Teachers of English ABSTRACT In keeping with efforts of the National Council of Teachers of English to promote and recognize excellence in writing in the schools, this booklet presents the rankings of winning entries in the second year of NCTE's Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines in American and Canadian schools, and American schools abroad. Following an introduction detailing the evaluation process and criteria, the magazines are listed by state or country, and subdivided by superior, excellent, or aboveaverage rankings. Those superior magazines which received the program's highest award in a second evaluation are also listed. Each entry includes the school address, student editor(s), faculty advisor, and cost of the magazine. (HTH) ***********************************************w*********************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** National Council of Teachers of English 1111 Kenyon Road. Urbana. Illinois 61801 Programto Recognize Excellence " in Student LiteraryMagazines UJ 1985 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) Vitusdocument has been reproduced as roomed from the person or organization originating it 0 Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction Quality. -

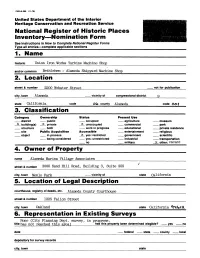

1. Name 6. Representation in Existing Surveys

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register off Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Union Iron Works Turbine Machine Shop and/or common Bethlehem - Alameda Shipyard Machine Shop 2. Location street & number 2200 Webster Street city, town Alameda vicinity of congressional district 9 state California code county Alameda code Oof 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private x unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process . x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military x other: vacant 4. Owner of Property name Alameda Marina Village Associates street & number 3000 Sand Hill Road, Building 3, Suite 255 city, town Menlo Park vicinity of state California 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Alameda County Courthouse street & number 1225 Fallen Street city, town Oakland state California 6. Representation in Existing Surveys None (City Planning Dept. survey, in progress, title has not reached this area)________has this property been determined elegible? yes no date . federal . state . county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent __ deteriorated __ unaltered x original site _x_good __ruins _x_ altered __moved date __ fair? * __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance See Continuation Sheet - page 8. -

High School Seniors... Apply for a Cal Grant Or the NEW Middle Class Scholarship - It Could Be Your Ticket to Success!

A Cal Grant is money you don’t have to pay back. It’s your ticket to CSU’s, UC’s, Private Colleges, Community Colleges, Career and Technical schools. High School Seniors... Apply for a Cal Grant or the NEW Middle Class Scholarship - it could be your ticket to success! Remember to submit your FAFSA or DREAM Act Application and Cal Grant GPA between January 1 - March 2, 2015 Attend a FREE Cash for College Workshop for a chance to cash in on a $2,000 scholarship! For assistance with completing your financial aid forms To find a 2015 workshop, visit: www.calgrants.org Steps to be Prepared: 1. Bring Student and Parent Social Security #’s (and Alien Registration #’s if you are not a U.S. Citizen). - If you don’t have either, come find out what financial aid options are available such as the CA DREAM Act and other scholarships. 2. Bring your family’s most recent Federal tax forms like 1040, W-2, bank statements, etc. You will not have to reveal this information to anyone, but you will need it to complete the forms. - If your family’s 2014 federal tax returns are not ready yet, bring 2013 tax returns for estimating. - To locate a FREE Tax Preparation Center in your neighborhood visit www.earnitkeepitsaveit.org (EarnIt!KeepIt!SaveIt! is a program of the United Way of the Bay Area.) 3. Submit a Cal Grant GPA Verification Form (or Release Form) to your counselor ASAP. Create a Webgrants 4 Students account to check the status of your award at: webgrants4students.org 4. -

EAGLE HOUSING 2437 Eagle Ave, Alameda, CA

AFFORDABLE MULTIFAMILY HOUSING MARKET STUDY EAGLE HOUSING 2437 Eagle Ave, Alameda, CA. Housing Authority of the City of Alameda ALAMEDA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for ALAMEDA HOUSING AUTHORITY JUNE 2016 Eagle Housing Alameda Market Area TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE COVER LETTER TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................... i LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................... iii LIST OF CHARTS ..........................................................................................................iv LIST OF EXHIBITS ........................................................................................................ v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. E-1 CHAPTER I - THE PROPOSED PROJECT – EAGLE HOUSING Project Description ........................................................................................1-1 Project Site ................................................................................................... 1-2 Adjacent Land Uses ...................................................................................... 1-2 Services and Facilities ................................................................................... 1-8 Other Services and Facilities......................................................................... 1-8 CHAPTER II - GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION AND AREA DESCRIPTION Alameda County -

Enroll Now for Summer and Fall

College of Alameda SCHEDULE OF CLASSES | SUMMER SESSIONS 2019| FALL SEMESTER 2019 Enroll Now for Summer and Fall Save Money on Three Summer Sessions: Textbooks! Six-week Session: June 17–July 26, 2019 Look for Zero-Textbook- Eight-week Session: June 17–August 9, 2019 Cost (ZTC) in the course InformationFour-week and classes Session: are subject July to change, 1–July please 26, see 2019 online schedule for the latest information. listings. FallSee Semester our website: http://bit.ly/PeraltaOnlineSchedule Dates: August 19–December 13, 2019 SUMMER /FALL 2018 1 Designed by Chris Gatmaitan College of Alameda 555 Ralph Appezzato Memorial Parkway, Alameda, CA 94501 President's Welcome Welcome to College of Alameda's Summer and Fall Semesters! We want you to be successful in your pursuit of a college education. Too often, students find the cost of college a challenge. Even with financial aid, grants, or scholarships, some students find that textbook costs are out of reach. Recently, College of Alameda has begun implementing a program allowing us to offer some classes with zero cost for textbooks. Instead of textbooks, a number of our innovative faculty have adopted Open Educational Resources (OER) and Zero-Textbook-Cost (ZTC) materials for their courses. Students enrolled in ZTC courses will use high-quality free resources instead of textbooks. These new ZTC classes will offer our students significant cost savings. Currently, College of Alameda offers ZTC courses in a variety of subject areas, including math, communications, geography, English, physics and more. Courses that offer ZTC can be found by looking in the class notes section of the course descriptions for the following information: “Cost Cutter Alert: This course section uses only zero-cost course materials. -

Alameda USD Supt Position Description 2019

Information for Applicants for the Position of SUPERINTENDENT Alameda Unified School District A Dynamic Professional Opportunity THE POSITION The Board of Education of the Alameda Unified School District invites highly qualified educational leaders to apply for the position of District Superintendent. PROFESSIONAL PROFILE The Alameda Unified School District seeks a superintendent who: ● Has a holistic child perspective ● Has experience as a superintendent ● Has a proven track record of growing academic achievement for ALL students ● Has experience working in a culturally diverse community ● Is a good listener, caring, and compassionate ● Has a “student first” attitude ● Is an instructional leader ● Is an advocate of both college and career readiness ● Has good fiscal management and fund allocation ● Considers the long-term impacts to all students when making decisions ● Can facilitate the development of a new vision, with implementation strategies ● Employs collaborative leadership skills ● Can discover and access community resources ● Builds trust among all stakeholders in the district and community ● Is a systems thinker, manager ● Has a record of closing the achievement gap ● Has experience with driving a strategic plan PERSONAL PROFILE The Alameda Unified School District seeks a superintendent who: ● Is honest, trustworthy, ethical and confidential ● Is approachable and committed to the district ● Is collaborative and inclusive, an active listener ● Is creative and innovative; receptive to others’ ideas ● Is passionate and compassionate -

School‐Based Health Center School County Phone City Medica L Menta L

School‐Based Health Center School County Phone City Medical Education Repro Health, Mental Health Comprehensive Youth Engagment Dental Treatment Dental Prevention Community Health Alameda Family Services School‐Based Health Center ‐ Alameda Alameda High School Alameda (510) 337‐7006 Alameda Alameda Family Services School‐Based Health Center ‐ Encinal Encinal High School Alameda (510) 748‐4085 Alameda Berkeley High School Health Center Berkeley High School Alameda (510) 644‐6965 Berkeley Berkeley Tech Health Center Berkeley Technology Academy (B‐Tech) Alameda (510) 644‐6159 Berkeley Chappell Hayes Health Center McClymonds Educatiol Complex Alameda (510) 835‐1393 Oakland Elmhurst Campus SBHC Elmhurst Community Prep School and Alliance Academy Alameda (510) 639‐1479 Oakland Frick Middle School Health Center Frick Middle School Alameda (510) 639‐3386 Oakland Fuente Wellness Center San Lorenzo Unified School District Alameda (510) 481‐4500 San Leandro Havenscourt Campus SBHC Coliseum College Prep and ROOTS Academy Alameda (510) 639‐1981 Oakland Hawthorne Clinic Urban Promise Academy Middle School Alameda (510) 715‐5611 Oakland Hayward High Mobile SBHC Hayward High School Alameda Hayward Island HS Family Health Services Island High School Alameda (510) 337‐7006 Alameda Logan Health Center James Logan High School Alameda (510) 690‐6044 Union City Madison Health Center Madison Park Business & Art Academy Alameda (510) 636‐4210 Oakland Piedmont High School Wellness Center Piedmont High School -

Dubai Star Incident SCAT 11/04

Ohlone Park Moraga Cesar Chavez State Park James Kenney Rec Center Park AL A11A Univ of Cal Berkeley Albany University Downtown Berkeley Bart Station University Eastshore State Park StSt JosephJoseph thethe WorkerWorker ElemElem SCHSCH 6th BlackBlack PinePine CircleCircle ElemElem SchoolSchool Bancroft Strawberry Creek Park Sacramento ArmstrongArmstrong UniversityUniversity AL A11B Shattuck Maybeck High School 80 BerkwoodBerkwood HedgeHedge ElemElem SchoolSchool BerkeleyBerkeley HighHigh SchoolSchool Horseshoe Park Columbus Elementary School Claremont Canyon Reg Preserve AL A11D Herrick Memorial Hospital Shattuck Bancroft AL A11E Dwight AL A11C AL A11F Shorebird Park 123 Martin Luther King Jr G r Orinda Willard Park iz z EastEast CampusCampus HighHigh SchoolSchool l Willard Middle School y Grizzly Peak Open Space Park P e Berkeley AL A19 a k 7th LongfellowLongfellow ArtsArts andand TechTech MSMS Berkeley Aquatic Park LeLe ConteConte ElementaryElementary SchoolSchool AL A11 AL A11G Adeline JohnJohn MuirMuir ElementaryElementary SchoolSchool Grove Rec Center Park San Pablo Park Alta Bates Medical Center EcoleEcole BilingueBilingue ElemElem SchoolSchool College Malcolm X Elementary School Adeline 13 Ashby Bart Station Henry J Kaiser Jr Elem School Tunnel Road Park AL A18 Telegraph SaintSaint AugustineAugustine ElementaryElementary SCHSCH Patton Caldecott Division A Chabot Recreation Area PeraltaPeralta ElementaryElementary SchoolSchool Alcatraz 24 SheltonsSheltons PrimPrim EdEd ElemElem SchoolSchool n AnthonyAnthony ChabotChabot ElemElem