Proceedings of the First International Colin Wilson Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malleus Monstrorumsampleexpanded English File Edition Is Published by Chaosium Inc

Sample file —EXPANDED ENGLISH EDITION IN 380 ENTRIES— by Scott David Aniolowski with Sandy Petersen & Lynn Willis Additional Material by: David Conyers, Keith Herber, Kevin Ross, ChadSample J. Bowser, Shannon file Appel, Christian von Aster, Joachim A. Hagen, Florian Hardt, Frank Heller, Peter Schott, Steffen Schuütte, Michael Siefner, Jan Cristof Steines, Holger Göttmann, Wolfang Schiemichen, Ingo Ahrens, and friends. For fuller Author credits see pages 4 and 288. Project & Layout: Charlie Krank Cover Painting: Lee Gibbons Illustrated by: Pascal D. Bohr, Konstantyn Debus, Nils Eckhardt, Thomas Ertmer, Kostja Kleye, Jan Kluczewitz, Christian Küttler, Klaas Neumann, Patrick Strietzel, Jens Weber, Maria Luisa Witte, Lydia Ortiz, Paul Carrick. Art direction and visual concept: Konstantyn Debus (www.yllustration.com) Participants in the German Edition: Frank Heller, Konstantyn Debus, Peter Schott, Thomas M. Webhofer, Ingo Ahrens, Jens Kaufmann, Holger Göttmann, Christina Wessel, Maik Krüger, Holger Rinke, Andreas Finkernagel, 15brötchenmann Find more information at www.pegasus.de German to English Translation: Bill Walsh Layout Assistance: Alan Peña, Lydia Ortiz Chaosium is: Lynn Willis, Charlie Krank, Dustin Wright, Fergie, and a few odd critters. A CHAOSIUM PUBLICATION • 2006 M’bwa, megalodon, the Million Favoured Ones, the Complete Credits mind parasites, the miri nigri, M’nagalah, Mordiggian, moose, M’Tlblys, the nioth-korghai, Nug & Yeb, octo- Scott David Aniolowski: the children of Abhoth, pus, Ossadagowah, Othuum, the minions of Othuum, -

Extraterrestrial Places in the Cthulhu Mythos

Extraterrestrial places in the Cthulhu Mythos 1.1 Abbith A planet that revolves around seven stars beyond Xoth. It is inhabited by metallic brains, wise with the ultimate se- crets of the universe. According to Friedrich von Junzt’s Unaussprechlichen Kulten, Nyarlathotep dwells or is im- prisoned on this world (though other legends differ in this regard). 1.2 Aldebaran Aldebaran is the star of the Great Old One Hastur. 1.3 Algol Double star mentioned by H.P. Lovecraft as sidereal The double star Algol. This infrared imagery comes from the place of a demonic shining entity made of light.[1] The CHARA array. same star is also described in other Mythos stories as a planetary system host (See Ymar). The following fictional celestial bodies figure promi- nently in the Cthulhu Mythos stories of H. P. Lovecraft and other writers. Many of these astronomical bodies 1.4 Arcturus have parallels in the real universe, but are often renamed in the mythos and given fictitious characteristics. In ad- Arcturus is the star from which came Zhar and his “twin” dition to the celestial places created by Lovecraft, the Lloigor. Also Nyogtha is related to this star. mythos draws from a number of other sources, includ- ing the works of August Derleth, Ramsey Campbell, Lin Carter, Brian Lumley, and Clark Ashton Smith. 2 B Overview: 2.1 Bel-Yarnak • Name. The name of the celestial body appears first. See Yarnak. • Description. A brief description follows. • References. Lastly, the stories in which the celes- 3 C tial body makes a significant appearance or other- wise receives important mention appear below the description. -

Lost Knowledge of the Imagination

Praise for Gary Lachman “The Lost Knowledge of the Imagination rejoins the parted Red Sea of modern intellect, demonstrating how rationalism and esotericism are not divided forces but necessary complements and parts of a whole in the human wish for understanding. More still, he elevates the relevancy of spiritual philosophies that we are apt to short-shrift, from Crowley to positive thinking, and issues a warning: If thoughts are causative, it is all the more vital that we, the thinkers, know ourselves.” Mitch Horowitz, PEN Award-winning author of Occult America and One Simple Idea: How Positive Thinking Reshaped Modern Life “A cracking author.” Lynn Picknett, Magonia Review of Books “Lachman is an easy to read author yet has a near encyclopaedic knowledge of esotericism and is hence able to offer many different perspectives on the subject at hand.” Living Traditions magazine “Lachman’s sympathetic, but not uncritical, account of [Rudolf Steiner’s] life is to be recommended to anyone who wishes to be better informed about this gifted and remarkable man.” Kevin Tingay, The Christian Parapsychologist “Lachman challenges many contemporary theories by reinserting a sense of the spiritual back into the discussion” Leonard Schlain, author of The Alphabet Versus the Goddess “Lachman’s depth of reading and research are admirable.” Scientific and Medical Network Review For Kathleen Raine (1908-2003), who showed the way Contents Title Page Dedication Acknowledgments Chapter One: A Different Kind of Knowing Chapter Two: A Look Inside the World Chapter Three: The Knower and the Known Chapter Four: The Way Within Chapter Five: The Learning of the Imagination Chapter Six: The Responsible Imagination Further Reading Also by Gary Lachman Copyright Acknowledgments My thanks go to my editor Christopher Moore for taking on the project and to the staff of the British Library where most of the research was done. -

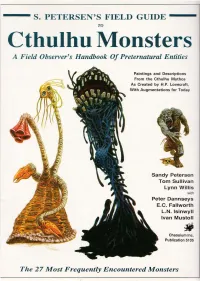

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book. -

The Occult Webb

-ii- T H E O C C U L T W E B B An Appreciation of the Life and Work of James Webb Compiled by John Robert Colombo With Contributions from Colin Wilson Joyce Collin-Smith Gary Lachman COLOMBO & COMPANY Second Enlarged Edition Copyright (c) 1999 by J.R. Colombo Copyright (c) 2015 by J.R. Colombo Contributions Copyright (c) 1999 & 2015 by Colin Wilson Copyright (c) 1999 & 2015 by Joyce Collin-Smith Copyright (c) 2001 & 2015 by Gary Lachman All Rights Reserved. Printed in Canada. ISBN 978-1-894540-79-7 Colombo & Company 42 Dell Park Avenue Toronto M6B 2T6 Canada Phone 1 (416) 782 6853 Fax 1 (416) 782 0285 Email [email protected] Homepage www.colombo.ca -iv- C O N T E N T S Preface, 1 Preface to the Second Edition, 3 Acknowledgements, 7 1. Biographical Notes, 10 2. Bibliographical Notes, 13 3. References, 27 4. James Webb and the Occult, 38 (Colin Wilson) 5. A Precognitive Dream, 57 (Joyce Collin-Smith) 6. “The Curious Nature of the Human Mind”: An Appreciation of James Webb, 61 (Joyce Collin-Smith) 7. “So I’m Pausing for a Moment”: An Appreciation of Jamie, 77 (Joyce Collin-Smith) 8. “The Strange Death of James Webb”: An Appreciation of the Late James Webb, 92 (Gary Lachman) L’Envoi, 102 -v- P R E F A C E The idea of Tradition has been made familiar by poets and philosophers, and disreputable by occultists of every description. J.W., The Harmonious Circle This monograph is an appreciation of the life and work of James Webb. -

Lovecraft Patrons

Lovecraft Patrons Subclasses Specific to Various Great Old Ones of the Cthulhu Mythos By Zach Hitzeroth DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, D&D Adventurers League, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. All characters and their distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission Sampleof Wizards of the Coast. file ©2020 Wizards of the Coast LLC, PO Box 707, Renton, WA 98057-0707, USA. Manufactured by Hasbro SA, Rue Emile-Boéchat 31, 2800 Delémont, CH. Represented by Hasbro Europe, 4 The Square, Stockley Park, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB11 1ET, UK. Note on Expanded Spell Lists Player's Handbook Only Spells Spells marked with an asterisk are from Xanathar's 4th Level: fabricate Guide to Everything. If your DM does not allow these spells, alternate spells from the Player's Handbook can be found at the end of each subclass. Abhoth Also known as the Source of Uncleanliness, Abhoth is an Outer God depicted as an ooze or slime from which monsters and unnamable horrors crawl from. Followers of Abhoth tend to spread disease and carry oozes around with them to symbolize their patron. Expanded Spell List Abhoth lets you choose from an expanded list of spells when you learn a warlock spell. -

The H. P. Lovecraft Tarot

The H. P. Lovecraft Tarot This interesting tarot deck was originally published in 1997 in a limited run and sold our fairly quickly, making it one of the most sought-after tarot decks on the market. This is one of the rare cases where you will actually hear these words: "Due to popular demand." This deck is the second printing from 2000, it is a blue deck, the 1st prinitng was red. Collectors take note! Each card in the deck is done in a dark, blue (1st printing) then red (2nd printing). Monochromatic decks appeal to me very much! The image is centered in the card and on the average has a lot of good detail which is easy enough to see. The border is also in the dark blue colour, but there is not enough contrast in this printing to clearly make out the text on the borders. You can see that it is there though, but you have to hold the cards fairly close to the light and angle them around a bit until you have made out each word. In the top center of the border is an eye. Pentacles are on the sides and the title at the bottom; the four corners have the suit icon itself on each card. Fortunately the little booklet has a legend in the back which shows the suit icons more clearly. In this deck, the figures of the Major Arcana are taken from various works of Lovecraft himself. The booklet that comes with this deck stresses that the Major Arcana cards have more power and influence over a reading than the Minor Arcana. -

LIVINGS Edward-Thesis.Pdf

OPEN SILENCE: AN APPLICATION OF THE PERENNIAL PHILOSOPHY TO LITERARY CREATION by EDWARD A R LIVINGS Principal Supervisor: Professor John McLaren Secondary Supervisor: Mr Laurie Clancy A thesis submitted in complete fulfilment of the requirements for PhD, 2006. School of Communication, Culture and Languages Victoria University of Technology © Edward A R Livings, 2006 Above the senses are the objects of desire, above the objects of desire mind, above the mind intellect, above the intellect manifest nature. Above manifest nature the unmanifest seed, above the unmanifest seed, God. God is the goal; beyond Him nothing. From the Kāthak Branch of the Wedas (Katha-Upanishad)1 1 Shree Purohit Swāmi and W B Yeats, trans., The Ten Principal Upanishads (1937; London: Faber and Faber, 1985) 32. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge the efforts of my supervisors Professor John McLaren and Laurie Clancy and those of John Jenkins, Jordie Albiston and Joanna Steer, all of whom contributed, directly or indirectly, to the production of this thesis and to whom I am most grateful. I hope the quality of the dissertation reflects the input of these people, who have so ably assisted in its production. Any faults found within the thesis are attributable to me only. 3 ABSTRACT Open Silence: An Application of the Perennial Philosophy to Literary Creation is a dissertation that combines a creative component, which is a long, narrative poem, with a framing essay that is an exegesis on the creative component. The poem, entitled The Silence Inside the World, tells the story of four characters, an albino woman in a coma, an immortal wizard, a dead painter, and an unborn soul, as they strive to comprehend the bizarre, dream-like realm in which they find themselves. -

The Apocalypse

ACT III – THE APOCALYPSE APOCALYPSE MOOD HOPEFUL BEATS You catch sight of a mother nursing a newborn, clearly born since the apocalypse began. You find an apple in your pocket that you remember putting there only now that you see it again. It’s still good, crisp and sweet. A young woman passing in the other direction looks up into your eyes and must see the depth of the despair that haunts you, because she reaches out suddenly, takes your hand, and says simply, “It’s going to be OK.” Before smiling ever so briefly and moving on before you can say anything. You can see a chicken cross the road. You look again: Yes. A chicken, a road. You laugh out load. SINISTER BEATS You run your hands through your hair, and they come away dusted with the infernal ash that blankets the whole world, an inescapable reminder of everything horrible, your whole universe crashing down around you. You come around a corner, and a desperate man, unshaven for a month, hair unkempt, points a trembling knife at your chest and demands any food you have on you. But then his knife falls out of his hand, and he runs away from you, sobbing. You walk through a stinking cloud, the smell of sulfur catching in your throat and making you gag. You’re jarred from slumber into terrified wakefulness by a crack of thunder. Your heart pounds. It will probably be an hour before you can find the realm of sleep again. Act 3.2 – Apocalypse 1 APOCALYPSE SPINE SEQUENCE 1: THE APOCALYPSE BEGINS SEQUENCE 2: REVELATION OF AZATHOTH SEQUENCE 3: SCENES FROM THE APOCALYPSE SEQUENCE 4: JOURNEY TO SAVANNAH – THE EYE OF THE STORM FINALE: RETURN TO JOY GROVE EPILOGUE REVELATION LIST – NPCs EDGAR JOB REFERENCE – STABILITY LOSS IN THE APOCALYPSE Roughly speaking, stability loss during each sequence (including the Return to Joy Grove finale) is capped at 6 points. -

Purim Passover Workshops

BULLETIN WINTER 2021 Spring Classes MONDAYS Wilshire Fitness with Sara Berg 9:30 - 10:30 a.m. Music Matters with Cantor Don Gurney 12:00 - 1:00 p.m. TUESDAYS Ten Amazing Jewish Women in History You’ve Never Heard Of with Rabbi Susan Nanus SERVICES @home 12:00 - 1:00 p.m. WEDNESDAYS El Judaismo Sepharadi: Exploring Sephardic Customs, Culture, and Ideas with Rabbi Daniel Bouskila 9:30 -10:15 a.m. From Our Clergy and Their Mentors 12:00 - 1:00 p.m. Purim Passover Workshops March 10 - The Preparation to March 17 - The Seder March 24 - Sharing Traditions, Passover Haggadahs, and Recipes THURSDAYS Wilshire Fitness with Sara Berg 9:30-10:30 a.m. Understanding the Holocaust with Holocaust Educator IN THIS The Jewish Significance of Triangles .............. 2 Randy Fried The Summer of 20Twenty-Fun ...................... 5 12:00 - 1:00 p.m. ISSUE Welcome University Synagogue ..................... 6 Creative Additions to Your Seder Plate............ 8 COMMENTARY What Does Haman Really Represent? While it is well known that the character of Haman in the Purim While we typically link Haman’s evil ways to the lineage of story represents an existential threat to the Jews of ancient Amalek and the unending forces attempting to eradicate the Persia, recent scholarship has revealed that Haman symbolizes Jewish people, there is a more accurate and mathematical a far more menacing and dangerous universal symbol. link between Haman and the forces of evil. Haman’s hat is the According to Biblical, Kabbalistic, and Zoroastrian sources, clue. Beginning around 2900 BCE, the underground forces Haman represents the intergalactic visitation of anti-Semitic of triangular domination began to make themselves known. -

Boletin Indice 36

BOLETÍN DE SUMARIOS Esta nueva entrega del Boletín de Sumarios recoge 174 nuevos números, correspondientes a 62 títulos distintos, recibidos en la Biblioteca durante los meses de octubre, noviembre y diciembre de 2013. Ordenados alfabéticamente, los títulos van seguidos de los números recibidos que, mediante enlaces, permiten acceder a los sumarios correspondientes. Si desea consultar alguna de estas revistas, puede hacerlo en la Sala de Lectura de la Biblioteca de Cultura. La mayoría de ellas se encuentra también en la Biblioteca Nacional. Si usted se encuentra fuera de Madrid, puede dirigirse a la Red de Bibliotecas de su Comunidad. Confiamos en que la información que ofrecen estos boletines sea de utilidad y rogamos remitan cualquier sugerencia sobre este servicio al buzón [email protected] Secretaría General Técnica Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones Ábaco: Revista de Cultura y Ciencias Sociales. Vol. 75: núm. 1 (2013) ADE Teatro. Núms. 147, 148 (2013) Anales del Museo de América. Vol. XIX (2011) Arquitectura viva. Núm. 156 (2013) Arte y Parte. Núms. 103, 104, 105. 106, 107, 108 (2013) BBF: Bulletin des Bibliothèques de France. Núms. 5, 6 (2013) BJC: Boletín de Jurisprudencia Constitucional. Núm. 377 (2013) Boletín de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza. Núms. 89-90, 91-92 (2013) Clarín: Revista de Nueva Literatura. Núms. 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108 (2013) Claves de razón práctica. Núms. 226, 227, 228, 229, 230, 231 (2013) CLIJ: Cuadernos de Literat. Infantil y Juvenil. Núms. 251, 252, 253, 254, 255, 256 (2013) Croquis, El. Núms. 165, 166, 167, 168-169 (2013) Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos. Núms. 760, 761, 762 (2013) Cultural Trends. -

The Innsmouth Conspiracy

Campaign Guide THE INNSMOUTH CONSPIRACY randomized facedown. Keys can enter play via several different card In the Deep, They Thrive effects, and they are usually placed on an enemy, location, or story “It was a town of wide extent and dense construction, yet one asset. Keys can be acquired in any of three ways: with a portentous dearth of visible life.” Æ If a location with a key on it has no clues, an investigator may take – H. P. Lovecraft,The Shadow over Innsmouth control of each of the location’s keys as a ability. The Innsmouth Conspiracy is a campaign for Arkham Horror: The Æ If an investigator causes an enemy with a key on it to leave play, that Card Game for 1–4 players. The Innsmouth Conspiracy deluxe investigator must take control of each of the keys that were on that expansion contains two scenarios: “The Pit of Despair” and “The enemy. (If it leaves play through some other means, place its keys Vanishing of Elina Harper.” These scenarios can be played on their on its location.) own or combined with the six Mythos Packs in The Innsmouth Æ Some card effects may allow an investigator to take control of keys Conspiracy cycle to form a larger eight‑part campaign. in other ways. Additional Rules and Clarifications When an investigator takes control of a key, they flip it faceup (if it is facedown) and place it on their investigator card. If an investigator who controls one or more keys is eliminated, place each of their keys on Keys their location.