Modernist Resistances to Psychoanalysis DISSERTATION Submitted in P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D. H. Lawrence and the Idea of the Novel D

D. H. LAWRENCE AND THE IDEA OF THE NOVEL D. H. LAWRENCE AND THE IDEA OF THE NOVEL John Worthen M MACMILLAN ~) John Worthen 1979 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1979 978-0-333-21706-1 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 1979 Reprinted 1985 Published by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke. Hampshir!' RG21 2XS and London Companies and representativ!'s throughout the world British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Worthl'n, John D. H. Lawrence and the Idea of the Novel I. Lawrence. David Herbert Criticism and interpretation I. Title 823' .9'I2 PR6023.A93Z/ ISBN 978-1-349-03324-9 ISBN 978-1-349-03322-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-03322-5 Contents Preface Vll Acknowledgements IX Abbreviations XI Note on the Text Xlll I The White Peacock I 2 The Trespasser 15 3 Sons and Lovers 26 4 The Rainbow 45 5 Women in Love 83 6 The Lost Girl 105 7 Aaron's Rod 118 8 Kangaroo 136 9 The Plumed Serpent 152 10 Lady Chatterley's Lover 168 II Lawrence, England and the Novel 183 Notes 185 Index 193 Preface This is not a book of novel theory. -

A Study of the Captain's Doll

A Study of The Captain’s Doll 論 文 A Study of The Captain’s Doll: A Life of “a Hard Destiny” YAMADA Akiko 要 旨 英語題名を和訳すると,「『大尉の人形』研究──「厳しい宿命」の人 生──」になる。1923年に出版された『大尉の人形』は『恋する女たち』, 『狐』及び『アルヴァイナの堕落』等の小説や中編小説と同じ頃に執筆さ れた D. H. ロレンスの中編小説である。これらの作品群は多かれ少なかれ 類似したテーマを持っている。 時代背景は第一次世界大戦直後であり,作品の前半の場所はイギリス軍 占領下のドイツである。主人公であるヘプバーン大尉はイギリス軍に所属 しておりドイツに来たが,そこでハンネレという女性と恋愛関係になる。し かし彼にはイギリスに妻子がいて,二人の情事を噂で聞きつけた妻は,ドイ ツへやってきて二人の仲を阻止しようとする。妻は,生計を立てるために人 形を作って売っていたハンネレが,愛する大尉をモデルにして作った人形 を見て,それを購入したいと言うのだが,彼女の手に渡ることはなかった。 妻は事故で死に,ヘプバーンは新しい人生をハンネレと始めようと思う が,それはこれまでの愛し愛される関係ではなくて,女性に自分を敬愛し 従うことを求める関係である。筆者は,本論において,この関係を男性優 位の関係と捉えるのではなくて,ロレンスが「星の均衡」の関係を求めて いることを論じる。 キーワード:人形的人間,月と星々,敬愛と従順,魔力,太陽と氷河 1 愛知大学 言語と文化 No. 38 Introduction The Captain’s Doll by D. H. Lawrence was published in 1923, and The Fox (1922) and The Ladybird (1923) were published almost at the same time. A few years before Women in Love (1920) and The Lost Girl (1921) had been published, too. These novellas and novels have more or less a common theme which is the new relationship between man and woman. The doll is modeled on a captain in the British army occupying Germany after World War I. The maker of the doll is a refugee aristocrat named Countess Johanna zu Rassentlow, also called Hannele, a single woman. She is Captain Hepburn’s mistress. His wife and children live in England. Hannele and Mitchka who is Hannele’s friend and roommate, make and sell dolls and other beautiful things for a living. Mitchka has a working house. But the captain’s doll was not made to sell but because of Hannele’s love for him. The doll has a symbolic meaning in that he is a puppet of both women, his wife and his mistress. -

A Psychoanalytic Interpretation of Pedagogical Presence

230 A Psychoanalytic Interpretation of Pedagogical Presence Between the Teacher’s Past and the Student’s Future: A Psychoanalytic Interpretation of Pedagogical Presence Trent Davis St. Mary’s University INTRODUCTION The rise and spread of totalitarianism in Europe in the twentieth century would forever haunt Hannah Arendt. She could never stop thinking about the destruction and pain it caused and whether there were political safeguards that could prevent anything like it from ever happening again. The difficulty with trying to secure such prevention, however, as she explains in The Human Condition, is that while there is a “basic unreliability”1 to people as individuals, there is also an “impossibility of foretelling the consequences”2 of any collective action. The awkward truth, in other words, is that the past can never guarantee the future. This year’s conference theme calls our attention to this Arendtian “gap” and what it might mean for the philosophy of education today. At first blush it appears to be merely debilitating to our educational hopes (if teaching and learning cannot secure the future, what can?). But in his recent book The Beautiful Risk of Education,3 Gert Biesta asks his readers to see both “weakness” and “risk” as not just acceptable, but even necessary, components of education. Given the current obsession with “strong” forms of teaching and learning that require measurable benchmarks for assessment, it is not hard to imagine why readers might be resistant to this request. Biesta frames his argument early in the text by offering a number of important distinctions. In the prologue he explains his conceptualization of the three “domains” of education. -

Syndicalism and Anarcho-Syndicalism in Germany: an Introduc- Tion

Syndicalism and Anarcho-Syndicalism in Germany: An Introduc- tion By Helge Döhring Published in 2004 Topics: IWA, Germany, SPD, history, World War I, unemployed workers, FAUD, FVdG Foreword The following text comprises an introduction to the development of German syndicalism from its beginnings in 1890 until the end of its organized form in the early 1960s. The emphasis of this introduction, however, centers on the period before and leading up to 1933, when the National Socialists under Adolf Hitler ascended to power. Syndicalism, and more specifically anarcho-syndicalism, are movements that have been largely forgotten. This albeit superficial outline should, at its conclusion, show that this movement was not always so obscure and unknown. This piece aims not to comprehensively examine all the varied aspects of German anarcho-syndicalism, but rather to pique the curiosity and interest of its readers. 1. What Does “Workers’ Movement” Mean? The first thing that one learns in studying the history of the workers’ movement, in Germany and elsewhere, is that the workers were organized primarily into the so-called “Workers’ Parties.” In Germany these took the form of the SPD [Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, Social Democratic Party of Germany] and the KPD [Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, Communist Party of Germany]. Upon further examination a number of other parties fall into view, for example Rosa Luxemburg’s Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD), or the CP’s other incarnations, the KAPD [Kommunistische Arbeiter-Partei Deutschlands, Communist Workers’ Party of Germany] and the SAPD [Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands, Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany]. And naturally the definition of the term “workers’ movement” places these political parties firmly in the foreground. -

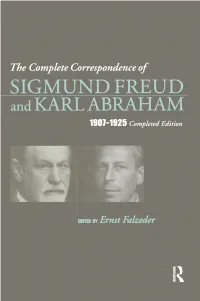

The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham

THE COMPLETE CORRESPONDENCE OF SIGMUND FREUD AND KARL ABRAHAM THE COMPLETE CORRESPONDENCE OF SIGMUND FREUD AND KARL ABRAHAM 1 9 0 7 - 1 9 2 5 Completed Edition transcribed and edited by Ernst Falzeder translated by Caroline Schwarzacher with the collaboration of Christine Trollope & Klara Majthenyi King Introduction by Andre Haynal & Ernst Falzeder First published 2002 by H. Karnac (Books) Ltd. Published 2018 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Freud material copyright© 1965, 2002 by A. W. Freud et al. Abraham material copyright © 1965, 2002 by the Estate of Grant Allan Editorial material and annotations copyright © 2002 by Ernst Falzeder Introduction copyright © 2002 by Andre Haynal Translation copyright © 2002 by Caroline Schwarzacher Facsimiles of letters on pp. ii, 442, and 495 and photographs on pp. xxii, xxv, and 453 reproduced by courtesy of the Freud Museum by agreement with Sigmund Freud Coprights Ltd. A Psycho-Analytic Dialogue. The Letters of Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham 1907-1926 (ed. Hilda C. Abraham and Ernst Freud). London: The Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1965. The rights of the authors, editor, and translator to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted in accordance with §§ 77 and 78 of the Copyright Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Five Formations of Publicity: Constitutive Rhetoric from Its Other Side

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF SPEECH, 2018 VOL. 104, NO. 2, 189–212 https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630.2018.1447140 Five formations of publicity: Constitutive rhetoric from its other side Jason D. Myres Communication Studies, University of Georgia, Athens, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This essay rethinks the constitutive formation of publics by Received 20 February 2017 foregrounding the desirability of publics themselves. This project Accepted 15 January 2018 begins by theoretically resituating publics as a series of KEYWORDS irrevocably lost objects. Specifically, I contend publics are Donald J. Trump; desire; composed of a montage of desires (oral, anal, phallic, scopic, and ’ public; prosopopeia; superego) modeled on Jacques Lacan s stages of the object in metonymy obsessional neurosis. To explicate, I use this schema to parse the symbolic dimensions of the “people” aligned with Donald J. Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign. Lacan’s schema of the object is adapted into a theory of publicity exemplified in the (astonishing) resilience of the “Trump voter,” the imaginary “people” routinely invoked throughout his emergence as a political figure. Lacan’s schema, I argue, helps explain the symbolic staging of the “Trump voter” as something more than just another potent social imaginary: an object of desire. Working from recent scholarship of Barbara Biesecker, Christian Lundberg, Joshua Gunn, and a growing number of others, this essay theorizes public formation from the standpoint of desire. However, I have a different emphasis in mind: rather than studying the for- mation of publics, I demarcate five potential con-formations of publicity that undergird publics as epiphenomena. This schema of desire refers not to a universal structure, but a partitioning that introduces difference within and between modes of public formation. -

Anarchism's Appeal to German Workers, 1878

The centers of anarchist activity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries included Italy, Spain, France, and the United States. The German anarchist movement was small, even in comparison to other nations that were not major anarchist centers. Contemporaries and scholars had until recently mostly agreed on the cause: anarchism was simply unable to compete with German Social Democracy, whose explosive growth beginning in the 1870s reflected the organization and self-awareness of an advanced industrial proletariat. For Social Democrats and many scholars, even those of a non-Marxist stripe, this situation represented the inevitable triumph of mature, class-conscious socialism over the undisciplined and utopian impulses of prepolitical workers.1 Once socialism had developed into a mass movement, only the detritus of the lumpenproletariat, petit bourgeois reactionaries, and decadent elites embraced anarchism. In the late 1960s and 1970s German anarchism finally began to receive a modicum of scholarly attention.2 The small body of scholarship produced since has shown that a German anarchist movement (really, movements) did in fact exist throughout the era of the German Empire (1871- 1918) among the handful of anarchists committed to "propaganda of the deed" active in the 1880s, within a circle of cultural and intellectual anarchists in the following decade, and in the form of anarcho-syndicalism after the turn of the century. Several German anarchist leaders, intellectuals, and artists also received scholarly attention as individual thinkers.3 This scholarship did much to illuminate the social and intellectual history of German anarchism, but did not significantly alter the conventional understanding of German anarchism as an atavistic expression of protest destined to be eclipsed by Social Democracy. -

Introduction: Jung, New York, 1912 Sonu Shamdasani

Copyrighted Material IntroductIon: Jung, neW York, 1912 Sonu Shamdasani September 28, 1912. the New York Times featured a full-page inter- view with Jung on the problems confronting america, with a por- trait photo entitled “america facing Its Most tragic Moment”— the first prominent feature of psychoanalysis in the Times. It was Jung, the Times correctly reported, who “brought dr. freud to the recognition of the older school of psychology.” the Times went on to say, “[H]is classrooms are crowded with students eager to under- stand what seems to many to be an almost miraculous treatment. His clinics are crowded with medical cases which have baffled other doctors, and he is here in america to lecture on his subject.” Jung was the man of the hour. aged thirty-seven, he had just com- pleted a five-hundred-page magnum opus, Transformations and Sym‑ bols of the Libido, the second installment of which had just appeared in print. following his first visit to america in 1909, it was he, and not freud, who had been invited back by Smith ely Jelliffe to lec- ture on psychoanalysis in the new international extension course in medicine at fordham university, where he would also be awarded his second honorary degree (others invited included the psychiatrist William alanson White and the neurologist Henry Head). Jung’s initial title for his lectures was “Mental Mechanisms in Health and disease.” By the time he got to composing them, the title had become simply “the theory of Psychoanalysis.” Jung com- menced his introduction to the lectures by indicating that he in- tended to outline his attitude to freud’s guiding principles, noting that a reader would likely react with astonishment that it had taken him ten years to do so. -

Sigmund Freud Papers

Sigmund Freud Papers A Finding Aid to the Papers in the Sigmund Freud Collection in the Library of Congress Digitization made possible by The Polonsky Foundation Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2015 Revised 2016 December Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms004017 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm80039990 Prepared by Allan Teichroew and Fred Bauman with the assistance of Patrick Holyfield and Brian McGuire Revised and expanded by Margaret McAleer, Tracey Barton, Thomas Bigley, Kimberly Owens, and Tammi Taylor Collection Summary Title: Sigmund Freud Papers Span Dates: circa 6th century B.C.E.-1998 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1871-1939) ID No.: MSS39990 Creator: Freud, Sigmund, 1856-1939 Extent: 48,600 items ; 141 containers plus 20 oversize and 3 artifacts ; 70.4 linear feet ; 23 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in German, with English and French Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Founder of psychoanalysis. Correspondence, holograph and typewritten drafts of writings by Freud and others, family papers, patient case files, legal documents, estate records, receipts, military and school records, certificates, notebooks, a pocket watch, a Greek statue, an oil portrait painting, genealogical data, interviews, research files, exhibit material, bibliographies, lists, photographs and drawings, newspaper and magazine clippings, and other printed matter. The collection documents many facets of Freud's life and writings; his associations with family, friends, mentors, colleagues, students, and patients; and the evolution of psychoanalytic theory and technique. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. -

JDHLS Online

J∙D∙H∙L∙S Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies Citation details Article: ‘“Ausdruckstanz” and “Ars Amatoria”: D. H. Lawrence and the interrelated arts of dance and love Author: Earl G. Ingersoll Source: Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies, Vol. 4, No. 2 (2016) Pages: 73‒97 Copyright: individual author and the D. H. Lawrence Society. Quotations from Lawrence’s works © The Estate of Frieda Lawrence Ravagli. Extracts and poems from various publications by D. H. Lawrence reprinted by permission of Pollinger Limited (www.pollingerltd.com) on behalf of the Estate of Frieda Lawrence Ravagli. A Publication of the D. H. Lawrence Society of Great Britain JDHLS 2016, vol. 4, no. 2 73 “AUSDRUCKSTANZ” AND “ARS AMATORIA”: D. H. LAWRENCE AND THE INTERRELATED ARTS OF DANCE AND LOVE EARL G. INGERSOLL As Marina Ragachewskaya has recently indicated in this journal, Lawrence’s interest in the art of dance has received renewed attention in the 2010s.1 The subject has been thought to have opened with two notable investigations:2 ‘D. H. Lawrence and the Dance’ (1992) by Mark Kinkead-Weekes and then ‘Music and Dance in D. H. Lawrence’ (1997) by Elgin W. Mellown, who apparently was unaware that Kinkead-Weekes had blazed the trail before him, since his article contains no mention of this earlier work.3 Another writer who missed Kinkead-Weekes’s article, with its endnote citations from Martin Green’s Mountain of Truth: The Counterculture Begins, Ascona, 1900‒1920, was Terri Ann Mester, whose interpretations of dance scenes in Lawrence’s fiction could have benefited from even a cursory reading of Green’s 1986 study.4 Mester cites Deborah Jowitt’s Time and the Dancing Image, but she does not explore Jowitt’s very brief commentary upon Rudolf Laban and Mary Wigman, which might have provided her with yet another avenue of access to Green’s Mountain of Truth.5 To close this circle, Kinkead-Weekes then responded to Mester’s monograph in his keynote address at the 2003 International D. -

A Brief History of the British Psychoanalytical Society

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BRITISH PSYCHOANALYTICAL SOCIETY Ken Robinson When Ernest Jones set about establishing psychoanalysis in Britain, two intertwining tasks faced him: establishing the reputation of psychoanalysis as a respectable pursuit and defining an identity for it as a discipline that was distinct from but related to cognate disciplines. This latter concern with identity would remain central to the development of the British Society for decades to come, though its inflection would shift as the Society sought first to mark out British psychoanalysis as having its own character within the International Psychoanalytical Association, and then to find a way of holding together warring identities within the Society. Establishing Psychoanalysis: The London Society Ernest Jones’ diary for 1913 contains the simple entry for October 30: “Ψα meeting. Psycho-med. dinner” (Archives of the British Psychoanalytical Society, hereafter Archives). This was the first meeting of the London Psychoanalytical Society. In early August Jones had returned to London from ignominious exile in Canada after damaging accusations of inappropriate sexual conduct in relation to children. Having spent time in London and Europe the previous year, he now returned permanently, via Budapest where from June he had received analysis from Ferenczi. Once in London he wasted no time in beginning practice as a psychoanalyst, seeing his first patient on the 14th August (Diary 1913, Archives), though he would soon take a brief break to participate in what would turn out to be a troublesome Munich Congress in September (for Jones’s biography generally, see Maddox [2006]). Jones came back to a London that showed a growing interest in unconscious phenomena and abnormal psychology. -

Nederlands Film Festival

SHOCK HEAD SOUL THE SPUTNIK EFFECT Simon Pummell PRESS BOOK 12 / 02 / 12 INTERVIEWS TRAILERS LINKS SHOCK HEAD SOUL TRAILER Autlook Film Sales http://vimeo.com/36138859 VENICE FILM FESTIVAL PRESS CONFERENCE http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwqGDdQbkqE SUBMARINE TRANSMEDIA PROFILES Profiles of significant current transmedia projects http://www.submarinechannel.com/transmedia/simon-pummell/ GRAZEN WEB TV IFFR Special http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BrxtxmsWtbE SHOCK HEAD SOUL SECTION of the PROGRAMME http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-se5L0G7pzM&feature=related BFI LFF ONLINE SHOCK HEAD SOUL LFF NOTES http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5xX6iceTG8k The NOS radio interview broadcasted and can be listened to online, http://nos.nl/audio/335923‐sputnik‐effect‐en‐shock‐head‐soul.html. NRC TOP FIVE PICJ IFFR http://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2012/01/19/kaartverkoop-gaat-van-start-haal-het- maximale-uit-het-iffr/ SHOCK HEAD SOUL geselecteerd voor Venetië Film Festival... http://www.filmfestival.nl/nl/festival/nieuws/nederlandse-film... SHOCK HEAD SOUL geselecteerd voor Venetië Film Festival 28 juli 2011 De Nederlands/Engelse coproductie SHOCK HEAD SOUL van regisseur Simon Pummell met o.a. Hugo Koolschijn, Anniek Pheifer, Thom Hoffman en Jochum ten Haaf is geselecteerd voor de 68e editie van het prestigieuze Venetië Film Festival in het Orizzonti competitieprogramma. Het festival vindt plaats van 31 augustus tot en met 10 september 2011. Synopsis: Schreber was een succesvolle Duitse advocaat die in 1893 boodschappen van God doorkreeg via een ‘typemachine’ die de kosmos overspande. Hij bracht de negen daaropvolgende jaren door in een inrichting, geteisterd door wanen over kosmische controle en lijdend aan het idee dat hij langzaam van geslacht veranderde.