Detailed Study and Analysis of Some Gwalior Gharana Vocalists from the 20Th Century CHAPTER IV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 6 SOME NEWLY CREATED MISHRA RAGA

Chapter 6 SOME NEWLY CREATED MISHRA RAGA SOME NEW CREATIONS : Raga Jogkauns : (A landmark of modem mishra raga) This is an excellent creation of late Pt. Jagannath Buva Purohit "Gunidas". It is a combination of Raga Jog, Chandrakauns (both old and newly created by Prof. Devdhar). Chalan: tit Pi <4 - ST Pt Wf, FlI'PI’ll m n *r n n P( \ w n *t \st, v 3tj\stv X{ *f nji # \*tst^*ftPtsi^sft srPr tft *r *t, v i\5 *nt h *t, *rr Here, (1) Phrase *tT *1 *1*1 is used for raga Jog (2) Phrase *tT *1 *1 *IJHT is also used for raga Jog (3) Phrase tfT Pt «(P[ tn is used for raga Chandrakaus (4) Phrase 4 tfT is also used for raga Chandrakaus (5) Phrase *1 *t ^ ’s also used for raga Chandrakaus (6) Phrase 4 st Pi^st 4 is used for od Chandrakaus While discussing this raga with Prof. N.V.Patwardhan on 18/12/88 he told us that he had a wide discussion with Buva and Buva has told him that while creating the raga Jogkaus the old Chandrakaus having komal Nishad was in his mind. So he had used phrase 4 % 4... which now an identical phrase of raga Jogkaus ( *t tt 4t^t 4 4^44 ) Also discussing this raga with Pt. Arvind Parikh a sitar mastreo and disciple of Sh. Ustad VilayatKhan; he also told that he believes only one newly created mishra raga which may be called as a land mark of mishra raga is only raga Jogkaus created by Pt. -

Kothari International School Annual Academic Plan Subject-Hmv Grade-12 Session-2020-21 Weightage –Theory0-30 Marks

KOTHARI INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL ANNUAL ACADEMIC PLAN SUBJECT-HMV GRADE-12 SESSION-2020-21 WEIGHTAGE –THEORY0-30 MARKS /PRACTICAL-70 MARKS MONTH TOPIC SUB TOPICS BLOCK PERIODS MARCH THEORY- TO UNDERSTAND SHORT NOTES - THE MEANING & ALANKARA,VARNA,KA USE OF THESE 8.5 BLOCKS N,MEEND,KHATKA NOTES IN SINGING. APRIL RAGA BAGESHRI HOW TO SING SHORT NOTES- RAGA BAGESHRI 6 BLOCKS MURKI ,GAMAK WITH DRUTH LAYA ` TALA-DHAMAR RENDERING OF TAL BY HAND BEATS MAY LIFE SKETCH TO WRITE LIFE SANGEET PARIJAT SKETCH OF ABDUL DEFINITIONS- SADRA, KARIM KHAN & FAIYAJ 4.5 BLOCKS DADRA KHAN GRAM ,MURCHHANA ENABLE STUDENTS TO ,ALAP ,TANA APPLY THESE TERMS RAGA MALKOSH WHILE SINGING DRUT KHAYAL. TALA –JHAP TALA & TO STUDY RUPAK &UNDERSTAND TEEN 4.5 BLOCKS TAAL JULY TIME THEORY TO OF RAGA UNDERSTAND TALA-TILWADA THE VALUE OF THAH AND TIME IN RAGAS DUGUN TILWADA ON HAND BEATS SHORT HOW TO SING NOTE,VILAMBIT VILAMBIT 6 BLOCKS KHAYAL RAGA KHAHYALWITH BHAIRAV SIMPLE ELABORATIONS TALA DHAAMAR TO ENABLE STUDENTS HOW 6.5 BLOCKS LIFE SKETCH TO WRITE BADE NOTATION GULAMALI KHAN & TALA- KRISHNARAO DUGUN & THAH SHANKAR PANDIT AUGUST SHUDDHA AND TO UNDERSTAND VIKRIT SWARAS ABOUT SWARAS 6.5 BLOCKS RAGA BHAIRAV TO DEVELOP FOLK SONG PRACTICE OF BOOK -SANGEET SINGING RAGA RATNAKAR AND LIGHT MUSIC BRIEF STUDY OF BOOK. DHRUTH KHAYAL WITH ELLABORTATIONS 6.5 BLOCKS OF ALLAP,TAAN SEPTEMBER TO DEVELOP SHORT NOTES – KHAYAL 6 BLOCKS ALAP,TANA,SADRA,DADRA, SINGING STYLE GRAM,MURCHANA TALA TILWADA TO KNOW HOW VARIOUS PARTS OF TO SING DADRA 6 BLOCKS TANPURA TALA JHAPTAL,DHAMAR THAH ,DUGUN AND EKTAL CHAWGUNLAYA PRE – BOARD EXAMS OCTOBER PRE – BOARD EXAM 1 NOVEMBER PRE – BOARD EXAM 2 DECEMBER PRE – BOARD EXAM 3 . -

The Rich Heritage of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg On

Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda ||Shree DwaDwarrrrkeshokesho Jayati|| || Shree Vallabhadhish Vijayate || The Rich Heritage Of Dhrupad Sangeet in Pushtimarg on www.vallabhkankroli.org Reference : 8th Year Text Book of Pushtimargiya Patrachaar by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Inspiration: PPG 108 Shree Vrajeshkumar Maharajshri - Kankroli PPG 108 Shree Vagishkumar Bawashri - Kankroli Copyright © 2006 www.vallabhkankroli.org - All Rights Reserved by Shree Vakpati Foundation - Baroda Contents Meaning of Sangeet ........................................................................................................................... 4 Naad, Shruti and Swar ....................................................................................................................... 4 Definition of Raga.............................................................................................................................. 5 Rules for Defining Ragas................................................................................................................... 6 The Defining Elements in the Raga................................................................................................... 7 Vadi, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Vivadi [ Sonant, Consonant, Assonant, Dissonant] ................................ 8 Aroha, avaroha [Ascending, Descending] ......................................................................................... 8 Twelve Swaras of the Octave ........................................................................................................... -

HINDUSTANI MUSIC (Vocal)

H$moS> Z§. Code No. 33 /C amob Z§. narjmWu H$moS >H$mo CÎma-nwpñVH$m Ho$ _wI-n¥ð Roll No. >na Adí` {bIo§ & Candidates must write the Code on the title page of the answer-book. ZmoQ> NOTE (I) H¥$n`m Om±M H$a b| {H$ Bg àíZ-nÌ _o§ _w{ÐV (I) Please check that this question n¥ð> 7 h¢ & paper contains 7 printed pages. (II) àíZ-nÌ _| Xm{hZo hmW H$s Amoa {XE JE H$moS (II) Code number given on the right >Zå~a H$mo N>mÌ CÎma-nwpñVH$m Ho$ _wI-n¥ð> na hand side of the question paper {bI| & should be written on the title page of the answer-book by the candidate. (III) H¥$n`m Om±M H$a b| {H$ Bg àíZ-nÌ _| (III) Please check that this question >5 àíZ h¢ & paper contains 5 questions. (IV) H¥$n`m àíZ H$m CÎma {bIZm ewê$ H$aZo go (IV) Please write down the Serial nhbo, CÎma-nwpñVH$m _| àíZ H$m H«$_m§H$ Number of the question in the Adí` {bI| & answer-book before attempting it. (V) Bg àíZ-nÌ H$mo n‹T>Zo Ho$ {bE 15 {_ZQ >H$m (V) 15 minute time has been allotted to g_` {X`m J`m h¡ & àíZ-nÌ H$m {dVaU read this question paper. The nydm©• _| 10.15 ~Oo {H$`m OmEJm & question paper will be distributed at 10.15 a.m. From 10.15 a.m. -

The Concept of Tala 1N Semi-Classical Music

The Concept of Tala 1n Semi-Classical Music Peter Manuel Writers on Indian music have generally had less difficulty defining tala than raga, which remains a somewhat abstract, intangible entity. Nevertheless, an examination of the concept of tala in Hindustani semi-classical music reveals that, in many cases, tala itself may be a more elusive and abstract construct than is commonly acknowledged, and, in particular, that just as a raga cannot be adequately characterized by a mere schematic of its ascending and descending scales, similarly, the number of matra-s in a tala may be a secondary or even irrelevant feature in the identification of a tala. The treatment of tala in thumri parallels that of raga in thumn; sharing thumri's characteristic folk affinities, regional variety, stress on sentimental expression rather than theoretical complexity, and a distinctively loose and free approach to theoretical structures. The liberal use of alternate notes and the casual approach to raga distinctions in thumri find parallels in the loose and inconsistent nomenclature of light-classical tala-s and the tendency to identify them not by their theoretical matra-count, but instead by less formal criteria like stress patterns. Just as most thumri raga-s have close affinities with and, in many cases, ongms in the diatonic folk modes of North India, so also the tala-s of thumri (viz ., Deepchandi-in its fourteen- and sixteen-beat varieties-Kaharva, Dadra, and Sitarkhani) appear to have derived from folk meters. Again, like the flexible, free thumri raga-s, the folk meters adopted in semi-classical music acquired some, but not all, of the theoretical and structural characteristics of their classical counterparts. -

This Article Has Been Made Available to SAWF by Dr. Veena Nayak. Dr. Nayak Has Translated It from the Original Marathi Article Written by Ramkrishna Baakre

This article has been made available to SAWF by Dr. Veena Nayak. Dr. Nayak has translated it from the original Marathi article written by Ramkrishna Baakre. From: Veena Nayak Subject: Dr. Vasantrao Deshpande - Part Two (Long!) Newsgroups: rec.music.indian.classical, rec.music.indian.misc Date: 2000/03/12 Presenting the second in a three-part series on this vocalist par excellence. It has been translated from a Marathi article by Ramkrishna Baakre. Baakre is also the author of 'Buzurg', a compilation of sketches of some of the grand old masters of music. In Part One, we got a glimpse of Vasantrao's childhood years and his early musical training. The article below takes up from the point where the first one ended (although there is some overlap). It discusses his influences and associations, his musical career and more importantly, reveals the generous and graceful spirit that lay behind the talent. The original article is rather desultory. I have, therefore, taken editorial liberties in the translation and rearranged some parts to smoothen the flow of ideas. I am very grateful to Aruna Donde and Ajay Nerurkar for their invaluable suggestions and corrections. Veena THE MUSICAL 'BRAHMAKAMAL' - Ramkrishna Baakre (translated by Dr. Veena Nayak) It was 1941. Despite the onset of November, winter had not made even a passing visit to Pune. In fact, during the evenings, one got the impression of a lazy October still lingering around. Pune has been described in many ways by many people, but to me it is the city of people with the habit of going for strolls in the morning and evening. -

Shruti Sangeet Academy

Shruti Sangeet Academy https://www.indiamart.com/shruti-sangeet-academy/ We provide Hindustani Classical,Semi Classical,Light Compositions,Sanskrit Shlokas and Compositions etc. About Us The Shruti Sangeet Academy is blessed to have a very motivated, sincere and dedicated group of students. Current Students are enrolled at one of three levels; Beginers, Intermediate and Advanced, based on their experience and comfort with the art form. Students follow a curriculum based on that offered by the Gandharva Mahavidhalaya . Gandharva Mahavidyalaya is an institution established in 1939 to popularize Indian classical music and dance. The Mahavidyalaya (school) came into being to perpetuate the memory of Pandit Vishnu Digamber Paluskar, the great reviver of Hindustani classical music, and to keep up the ideals set down by him. The first Gandharva Mahavidyala was established by him on 5 May 1901 at Lahore. The institution was relocated to Mumbai after 1947 and has subsequently established its administrative office at Miraj, Sangli District, Maharashtra. Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, New Delhi was established in 1939 by Padma Shri Pt. Vinaychandra Maudgalaya, from the Gwalior gharana, today it is the oldest music school in Delhi and is headed by noted Hindustani classical singer, Madhup Mudgal. At the Shruti Sangeet Academy, students up on completion of their curriculum successfully, have the option of applying and testing for the following certifications; (1) Sangeet Praveshika, equivalent to matriculation (generally a... For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/shruti-sangeet-academy/aboutus.html F a c t s h e e t Nature of Business :Service Provider CONTACT US Shruti Sangeet Academy Contact Person: Manager A1-602 Parsvnath Exotica Sector 53 Gurgaon - 122001, Haryana, India https://www.indiamart.com/shruti-sangeet-academy/. -

12 NI 6340 MASHKOOR ALI KHAN, Vocals ANINDO CHATTERJEE, Tabla KEDAR NAPHADE, Harmonium MICHAEL HARRISON & SHAMPA BHATTACHARYA, Tanpuras

From left to right: Pandit Anindo Chatterjee, Shampa Bhattacharya, Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan, Michael Harrison, Kedar Naphade Photo credit: Ira Meistrich, edited by Tina Psoinos 12 NI 6340 MASHKOOR ALI KHAN, vocals ANINDO CHATTERJEE, tabla KEDAR NAPHADE, harmonium MICHAEL HARRISON & SHAMPA BHATTACHARYA, tanpuras TRANSCENDENCE Raga Desh: Man Rang Dani, drut bandish in Jhaptal – 9:45 Raga Shahana: Janeman Janeman, madhyalaya bandish in Teental – 14:17 Raga Jhinjhoti: Daata Tumhi Ho, madhyalaya bandish in Rupak tal, Aaj Man Basa Gayee, drut bandish in Teental – 25:01 Raga Bhupali: Deem Dara Dir Dir, tarana in Teental – 4:57 Raga Basant: Geli Geli Andi Andi Dole, drut bandish in Ektal – 9:05 Recorded on 29-30 May, 2015 at Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, NY Produced and Engineered by Adam Abeshouse Edited, Mixed and Mastered by Adam Abeshouse Co-produced by Shampa Bhattacharya, Michael Harrison and Peter Robles Sponsored by the American Academy of Indian Classical Music (AAICM) Photography, Cover Art and Design by Tina Psoinos 2 NI 6340 NI 6340 11 at Carnegie Hall, the Rubin Museum of Art and Raga Music Circle in New York, MITHAS in Boston, A True Master of Khayal; Recollections of a Disciple Raga Samay Festival in Philadelphia and many other venues. His awards are many, but include the Sangeet Natak Akademi Puraskar by the Sangeet Natak Aka- In 1999 I was invited to meet Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan, or Khan Sahib as we respectfully call him, and to demi, New Delhi, 2015 and the Gandharva Award by the Hindusthan Art & Music Society, Kolkata, accompany him on tanpura at an Indian music festival in New Jersey. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

DEFAULTER PART-A.Xlsx

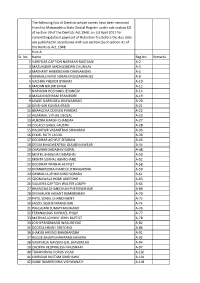

The following lists of Dentists whose names have been removed from the Maharashtra State Dental Register under sub-section (2) of section 39 of the Dentists Act,1948, on 1st April 2017 for committing default payment of Retention fee before the due date are published in accordance with sub section (5) of section 41 of the Dentists Act, 1948. Part-A Sr. No. Name Reg.No. Remarks 1 VARIFDAR CAPTION NARIMAN RUSTAMJI A-2 2 MAZUMDAR MADHUSNDAN CHUNILAL A-3 3 MAEHANT HARIKRISHAN DHANAMDAS A-5 4 GINWALS MINO SORABJI NUSSAWANJEE A-9 5 VACHHA PHEROX BYRAMJI A-10 6 MADAN BALBIR SINGH A-12 7 NARIMAN HOSHANG JEHANGIV A-14 8 MASANI BEHRAM FRAMRORE A-19 9 JAWLE NARENDEA BHAWANRAO A-20 10 DINSHAW KAVINA ERAEH A-21 11 BHARUCHA COOVER PHIRORE A-22 12 AGARWAL VITHAL DEOLAL A-23 13 AURORA HARISH CHANDAR A-27 14 COLACO ISABEL FAUSTIN A-28 15 HALDIPWR VASANTRAO SHAMRAO A-33 16 EEKIEL RUTH JACOB A-39 17 DEODHAR ACHYUT SITARAM A-43 18 DESIAI BHAGWENTRAI GULABSHAWEAR A-44 19 CHAVHAN SADASHIV GOPAL A-48 20 MISTRI JEHANGIR DADABHAI A-50 21 MEHTA SUKHAL ABHECHAND A-52 22 DEODHAR PRABHA ACHYUT A-58 23 DHANBHOORA MANECK JEHANGIRSHA A-59 24 GINWALLA JEHMI MINO SORABJI A-61 25 SOONAWALA HOMI ARDESHIR A-63 26 SIGUEIRA CAPTION WALTER JOSEPH A-65 27 BHANICHA DHANJISHAH PHERIZWSHAW A-66 28 DESHMUKH VASANT RAMKRISHAN A-70 29 PATIL SONAL CHANDHAKNT A-72 30 JAGOS JASSI BYARANSHAW A-74 31 PAHLAJANI SUMATI MUKHAND A-76 32 FERANANDAS RUPHAEL PHILIP A-77 33 MATHIAS JOHNNY JOHN BAPTIST A-78 34 JOSHI PANDMANG WASUDEVAO A-82 35 DCOSTA HENNY SERTORIO A-86 36 JHAKUR ARVIND BHAKHANDRA -

A Nonlinear Study on Time Evolution in Gharana

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 15 April 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201904.0157.v1 A NONLINEAR STUDY ON TIME EVOLUTION IN GHARANA TRADITION OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC Archi Banerjee1,2*, Shankha Sanyal1,2*, Ranjan Sengupta2 and Dipak Ghosh2 1 Department of Physics, Jadavpur University 2 Sir C.V. Raman Centre for Physics and Music Jadavpur University, Kolkata: 700032 India *[email protected] * Corresponding author Archi Banerjee: [email protected] Shankha Sanyal: [email protected]* Ranjan Sengupta: [email protected] Dipak Ghosh: [email protected] © 2019 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 15 April 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201904.0157.v1 A NONLINEAR STUDY ON TIME EVOLUTION IN GHARANA TRADITION OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC ABSTRACT Indian classical music is entirely based on the “Raga” structures. In Indian classical music, a “Gharana” or school refers to the adherence of a group of musicians to a particular musical style of performing a raga. The objective of this work was to find out if any characteristic acoustic cues exist which discriminates a particular gharana from the other. Another intriguing fact is if the artists of the same gharana keep their singing style unchanged over generations or evolution of music takes place like everything else in nature. In this work, we chose to study the similarities and differences in singing style of some artists from at least four consecutive generations representing four different gharanas using robust non-linear methods. For this, alap parts of a particular raga sung by all the artists were analyzed with the help of non linear multifractal analysis (MFDFA and MFDXA) technique. -

Artifacts and Representations of North Indian Art Music [*Ecompanion At

Oral Tradition, 20/1 (2005): 130-157 Shellac, Bakelite, Vinyl, and Paper: Artifacts and Representations of North Indian Art Music [*eCompanion at www.oraltradition.org] Lalita du Perron and Nicolas Magriel Introduction Short songs in dialects of Hindi are the basis for improvisation in all the genres of North Indian classical vocal music. These songs, bandiśes, constitute a central pillar of North Indian culture, spreading well beyond the geographic frontiers of Hindi itself. Songs are significant as being the only aspect of North Indian music that is “fixed” and handed down via oral tradition relatively intact. They are regarded as the core of Indian art music because they encapsulate the melodic structures upon which improvisation is based. In this paper we aim to look at some issues raised by the idiosyncrasies of written representations of songs as they has occurred within the Indian cultural milieu, and then at issues that have emerged in the course of our own ongoing efforts to represent khyāl songs from the perspectives of somewhat “insidish outsiders.” Khyāl, the focus of our current research, has been the prevalent genre of vocal music in North India for some 200 years. Khyāl songs are not defined by written representations, but are transmitted orally, committed to memory, and re-created through performance. A large component of our current project1 has been the transcription of 430 songs on the basis of detailed listening to commercial recordings that were produced during the period 1903-75, aspiring to a high degree of faithfulness to the details of specific performance instances. The shellac, bakelite, and vinyl records with 1 An AHRB-funded (Arts and Humanities Research Board) project, “Songs of North Indian Art Music” (SNIAM), carried out by the two authors in the Department of Music at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS).