A Multi-Phase Anglo-Saxon Site in Ewelme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Watlington • Pyrton • Shirburn December/January 2013

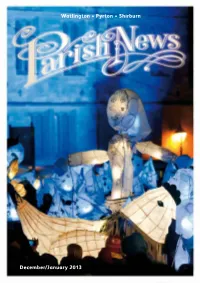

Watlington • Pyrton • Shirburn December/January 2013 1 CHRISTMAS WREATH MAKING WORKSHOPS B C J 2 Contents Dates for St.Leonards p.26-27 your diary Pyrton p.13 Advent Service of readings and Methodists p.14-15 music 4pm Sunday 2nd December Church services p.6-7 Christmas childrens services p.28 News from Registers p.33 Christmas Carol Services p.29 Ministry Team p.5 4 All Services p.19 Watlington Christmas Fair 1st Dec p.18 Christmas Tree Festival 8th-23rd December p.56 From the Editor A note about our Cover Page - Our grateful thanks to Emily Cooling for allowing us to use a photo of one of her extraordinary and enchanting Lanterns featured in the Local schools and community groups’ magical Oxford Lantern Parade. We look forward to writing more about Emily, a professional Shirburn artist; her creative children’s workshops and much more – Her website is: www.kidsarts.co.uk THE EDITORIAL TEAM WISH ALL OUR READERS A PEACEFUL CHRISTMAS AND A HEALTHY AND HAPPY NEW YEAR Editorial Team Date for copy- Feb/March 2013 edition is 8th January 2013 Editor…Pauline Verbe [email protected] 01491 614350 Sub Editor...Ozanna Duffy [email protected] 01491 612859 St.Leonard’s Church News [email protected] 01491 614543 Val Kearney Advertising Manager [email protected] 01491 614989 Helen Wiedemann Front Cover Designer www.aplusbstudio.com Benji Wiedemann Printer Simon Williams [email protected] 07919 891121 3 The Minister Writes “It’s the lights that get me in the end. The candlelight bouncing off the oh-so-carefully polished glasses on the table; the dim amber glow from the oven that silhouettes the golden skin of the roasting bird; the shimmering string of lanterns I weave through the branches of the tree. -

Goring (July 2019) • © VCH Oxfordshire • Landownership • P

VCH Oxfordshire • Texts in Progress • Goring (July 2019) • © VCH Oxfordshire • Landownership • p. 1 VCH Oxfordshire Texts in Progress Goring Landownership In the mid-to-late Anglo-Saxon period Goring may have been the centre of a sizeable royal estate, parts of which became attached to the burh of Wallingford (Berks.) following its creation in the late 9th century.1 By 1086 there were three estates in the parish, of which two can be identified as the later Goring and Gatehampton manors.2 Goring priory (founded before 1135) accrued a separate landholding which became known as Goring Priory manor, while the smaller manors of Applehanger and Elvendon developed in the 13th century from freeholds in Goring manor’s upland part, Applehanger being eventually absorbed into Elvendon. Other medieval freeholds included Haw and Querns farms and various monastic properties. In the 17th century Goring Priory and Elvendon manors were absorbed into a large Hardwick estate based in neighbouring Whitchurch, and in the early 18th Henry Allnutt (d. 1725) gave Goring manor as an endowment for his new Goring Heath almshouse. Gatehampton manor, having belonged to the mostly resident Whistler family for almost 200 years, became attached c.1850 to an estate focused on Basildon Park (Berks.), until the latter was dispersed in 1929−30 and Gatehampton manor itself was broken up in 1943. The Hardwick estate, which in 1909 included 1,505 a. in Goring,3 was broken up in 1912, and landownership has since remained fragmented. Significant but more short-lived holdings were amassed by John Nicholls from the 1780s, by the Gardiners of Whitchurch from 1819, and by Thomas Fraser c.1820, the first two accumulations including the rectory farm and tithes. -

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

A Short History of WHEATLEY STONE

A Short History of WHEATLEY STONE By W. O. HASSALL ILLUSTRATED BY PETER TYSOE 1955 Printed at the Oxford School of Art WHEATLEY STONE The earliest quarry at Wheatley to be named in the records is called Chalgrove, but it is not to be confused with the famous field of the same name where John Hampden was mortally wounded and which was transformed into an aerodrome during the war. Chalgrove in Wheatley lies on the edge of Wheatley West field, near the boundary of Shotover Park on the south side of the road from London to High Wycombe, opposite a turning to Forest Hill and Islip where a modern quarry is worked for lime, six miles East of Oxford. The name of Challrove in Wheatley is almost forgotten, except by the elderly, though the name appears in the Rate books. The exact position is marked in a map of 1593 at All Souls College and grass covered depressions which mark the site are visible from the passing buses. The All Souls map shows that some of these depressions, a little further east, were called in Queen Elizabeth’s reign Glovers and Cleves pits. The Queen would have passed near them when she travelled as a prisoner from Woodstock to Rycot on a stormy day when the wind was so rough that her captors had to hold down her dress and later when she came in triumph to be welcomed by the City and University at Shotover, on her way to Oxford. The name Chaigrove is so old that under the spelling Ceorla graf it occurs in a charter from King Edwy dated A.D. -

Three Ducks Cottage

THREE DUCKS COTTAGE 49 PRESTON CROWMARSH F WALLINGFORD F OXFORDSHIRE THREE DUCKS COTTAGE 49 PRESTON CROWMARSH F WALLINGFORD F OXFORDSHIRE Wallingford - 2 miles F Goring on Thames - 7 miles F Oxford - 12 miles F Reading - 14 miles F Henley on Thames - 12 miles F M40 at Lewknor (J.6) - 10 miles F M4 at Theale (J.12) - 17 miles F M4 at Maidenhead (J.8/9) - 19 miles (Distances approximate) In an idyllic pastoral setting overlooking historic grazing meadows leading down to the River Thames, a picturesque semi-detached thatched cottage listed Grade II dating from the middle of the 17th Century with well restored part beamed 3 bedroom character accommodation set in lawned gardens bordering meadows at the rear. F Unspoilt scenic setting by the Thames F Strategically well placed midway between Oxford and Reading with excellent road and rail communications F Historic small village off the beaten track a couple of minutes walk to Benson Marina and Lock F Quintessential period Cottage in stunning location F High speed Broadband connectivity available SITUATION F Front Sitting Room with fireplace The village of Preston Crowmarsh lies to the East of Wallingford on the banks of the Thames and approached off the Wallingford bypass thus benefitting from little traffic other than local residents. Little has changed over the centuries, the village retains its quiet rural charm and delightful F Kitchen with Breakfast Room landscape enhanced by numerous interesting period properties reflecting a rich architectural heritage linked to farming and agriculture. F Garden Room The ancient market town of Wallingford owes its importance largely to its position being approximately mid-way between Oxford and Reading F Landing with Loft access on the Icknield Way, at a natural fording point of the River Thames. -

Roakham Bottom Roke OX10 Contemporary Home in Sought After Village with Wonderful Country Views

Roakham Bottom Roke OX10 Contemporary home in sought after village with wonderful country views. A superb detached house remodelled and extended to create a very generous fi ve bedroom home. The accommodation mo notably features a acious entrance hall, modern kitchen, large si ing room with a wood burning ove and Warborough 1.8 miles, Wallingford doors out to the garden. The unning ma er bedroom has a 5 miles, Abingdon 11 miles, Didcot pi ure window to enjoy views of the garden and surrounding Parkway 11 miles (trains to London countryside. There is a utility room which benefi ts from doors to the front and rear. Paddington in 40 minutes)Thame 13 miles, Henley-On-Thames 13 miles, The house sits on a plot of approximately one third of an acre, Oxford 13 miles, Haddenham and which has been well planted to create a beautiful and very Thame Parkway 14 miles (Trains to private garden. There are many paved areas to use depending London Marylebone in 35 minutes) on the time of day. London 48 miles . (all times and Set well back from the lane the house is approached by a distances are approximate). gravel driveway o ering parking for several cars. There is also Local Authority: South Oxfordshire a car port for two cars which could be made into a garage with Di ri Council - 01235 422422 the addition of doors. There is a large workshop and in the rear garden a large summerhouse/ udio, currently used as a games room but could be converted into a home o ce. -

OXFORDSHIRE. [ KELLY's

390 PllB OXFORDSHIRE. [ KELLY's PUBLIC HOUSES-continued. GrapecS, Mrs. Charlotte Childs, 4 George street, Oxford Crown, .Arthur John Stanton, Charlton, Oxford Green Dragon, Henry Stone, 10 St. Aldate's st. Oxford Crown, William Waite, Souldern, Banbury Green Man, Charles Archer, Mollington, Banbury Crown inn, James N. Waters, Nuffield, Henley-on-Thms Green ::\Ian, Charles Bishop, Hi~moor,Henley-on-Thams Crown, Thomas "\'Vebb, Play hatch, Dunsden, Reading Greyhound, Miss Ellen Garlick, Ewelme, \Yallingf.ord Crown, Richard Wheeler, Stadhampton, "\Yallingford Greyhound, George King, Woodcote, Reading Crown inn, Mrs. R. Whichelo, Dorchester, \Yallingford Greyhound, Mrs. l\1. A. Vokins,Market pl.Henley-on-Thms Crown inn, James Alfred Whiting, 59a, Cornmkt. st.Oxfrd Greyhound, Harry \Villis, 10 Worcester street k Glou- Crown & Thistle, Mrs. H. Gardener, 10 Market st. Oxford cester green, Oxford Crown & Thistle, William Lee, Headington quarry,Oxford Griffin, Mrs. l\lartha Basson, K ewland, "\Yitney Crown & Tuns, Geo. J ones, New st. Deddington, Oxford Griffin, Charles Best, Church rd. Caversham, Reading Dashwood Arms, Benjamin Long, Kirtlington, Oxford Griffin inn, Charles Stephen Smith, Swerford, Enstone Dog inn, D. Woolford, Rotherfield Peppard,Henly.-on-T Half :Moon, James Bennett, 17 St. Clement's st. Oxford Dog & Anchor, Richard Young, Kidlington, Oxford Half ~Ioon, Thomas Bristow N eal, Cuxham, Tetsworth Dog & Duck, Thomas Page, Highmoor, Henley-on-Thms Hand &; Shears, Thomas Wilsdon,H'andborough,Woodstck Dog & Gun, John Henry Thomas, 6 North Bar st.Banbury Harcourt Arms, Charles Akers, Stanton Harcourt,Oxford Dog & Partridge, Thos. Warren, West Adderbury, Banbry Harcourt Arms, George ~Iansell, North Leigh, Witney Dolphin & Anchor, J. Taylor, 43 St. -

George Edmund Street

DOES YOUR CHURCH HAVE WORK BY ONE OF THE GREATEST VICTORIAN ARCHITECTS? George Edmund Street Diocesan Church Building Society, and moved to Wantage. The job involved checking designs submitted by other architects, and brought him commissions of his own. Also in 1850 he made his first visit to the Continent, touring Northern France. He later published important books on Gothic architecture in Italy and Spain. The Diocese of Oxford is extraordinarily fortunate to possess so much of his work In 1852 he moved to Oxford. Important commissions included Cuddesdon College, in 1853, and All Saints, Boyne Hill, Maidenhead, in 1854. In the next year Street moved to London, but he continued to check designs for the Oxford Diocesan Building Society, and to do extensive work in the Diocese, until his death in 1881. In Berkshire alone he worked on 34 churches, his contribution ranging from minor repairs to complete new buildings, and he built fifteen schools, eight parsonages, and one convent. The figures for Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire are similar. Street’s new churches are generally admired. They include both grand town churches, like All Saints, Boyne Hill, and SS Philip and James, Oxford (no longer in use for worship), and remarkable country churches such as Fawley and Brightwalton in Berkshire, Filkins and Milton- under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire, and Westcott and New Bradwell in Buckinghamshire. There are still some people for whom Victorian church restoration is a matter for disapproval. Whatever one may think about Street’s treatment of post-medieval work, his handling of medieval churches was informed by both scholarship and taste, and it is George Edmund Street (1824–81) Above All Saints, Boyne His connection with the Diocese a substantial asset for any church to was beyond doubt one of the Hill, Maidenhead, originated in his being recommended have been restored by him. -

The Post-Medieval Rural Landscape, C AD 1500–2000 by Anne Dodd and Trevor Rowley

THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000–2000 The Post-Medieval Rural Landscape AD 1500–2000 THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000-2000 The post-medieval rural landscape, c AD 1500–2000 By Anne Dodd and Trevor Rowley INTRODUCTION Compared with previous periods, the study of the post-medieval rural landscape of the Thames Valley has received relatively little attention from archaeologists. Despite the increasing level of fieldwork and excavation across the region, there has been comparatively little synthesis, and the discourse remains tied to historical sources dominated by the Victoria County History series, the Agrarian History of England and Wales volumes, and more recently by the Historic County Atlases (see below). Nonetheless, the Thames Valley has a rich and distinctive regional character that developed tremendously from 1500 onwards. This chapter delves into these past 500 years to review the evidence for settlement and farming. It focusses on how the dominant medieval pattern of villages and open-field agriculture continued initially from the medieval period, through the dramatic changes brought about by Parliamentary enclosure and the Agricultural Revolution, and into the 20th century which witnessed new pressures from expanding urban centres, infrastructure and technology. THE PERIOD 1500–1650 by Anne Dodd Farmers As we have seen above, the late medieval period was one of adjustment to a new reality. -

Vine Cottage Denton

Vine Cottage Denton Vine Cottage Denton, Oxfordshire Oxford 5 miles (trains to London Paddington), Haddenham and Thame Parkway 11 miles (trains to London Marylebone), Thame 10 miles, Abingdon 11 miles, Didcot 12 miles, London 55 miles (all times and di ances are approximate) A beautifully maintained period cottage with exquisite gardens in a quiet rural hamlet near Oxford. Hall | Drawing room | Kitchen/dining room | Study | Utility room | Cloakroom Four bedrooms | Two bath/shower rooms Deligh ul gardens | Raised beds | Pond | Vegetable garden | Green house | Summerhouse Potential to extend or convert the outbuildings into an annexe About 1 acre Knight Frank Oxford 274 Banbury Road Oxford, OX2 7DY 01865 264 879 harry.sheppard@knigh rank.com knigh rank.co.uk The Cottage Built in 1835, Vine Co age is a charming co age with much chara er set in an area of out anding natural beauty. The location of the property really is a naturi s, walkers and gardeners dream, in a rural position with panoramic views over open countryside. Whil feeling rural the property is conveniently close to the village of Cuddesdon which o ers a public house and a church and Oxford is only 5 miles away. Whil retaining many original chara er features the property has been sympathetically extended and has the advantage of not being li ed. Presented to an extremely high andard throughout. The majority of the roof was re-thatched in 2018, a new kitchen and shower room in alled in 2016 and the family bathroom was replaced in 2020. There is a high ecifi cation fi nish throughout the house including an integrated Sonos sy em and Boss eakers which complement the original chara er that has been beautifully re ored and maintained. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Early Medieval Oxfordshire

Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire Sally Crawford and Anne Dodd, December 2007 1. Introduction: nature of the evidence, history of research and the role of material culture Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire has been extremely well served by archaeological research, not least because of coincidence of Oxfordshire’s diverse underlying geology and the presence of the University of Oxford. Successive generations of geologists at Oxford studied and analysed the landscape of Oxfordshire, and in so doing, laid the foundations for the new discipline of archaeology. As early as 1677, geologist Robert Plot had published his The Natural History of Oxfordshire ; William Smith (1769- 1839), who was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire, determined the law of superposition of strata, and in so doing formulated the principles of stratigraphy used by archaeologists and geologists alike; and William Buckland (1784-1856) conducted experimental archaeology on mammoth bones, and recognised the first human prehistoric skeleton. Antiquarian interest in Oxfordshire lead to a number of significant discoveries: John Akerman and Stephen Stone's researches in the gravels at Standlake recorded Anglo-Saxon graves, and Stone also recognised and plotted cropmarks in his local area from the back of his horse (Akerman and Stone 1858; Stone 1859; Brown 1973). Although Oxford did not have an undergraduate degree in Archaeology until the 1990s, the Oxford University Archaeological Society, originally the Oxford University Brass Rubbing Society, was founded in the 1890s, and was responsible for a large number of small but significant excavations in and around Oxfordshire as well as providing a training ground for many British archaeologists. Pioneering work in aerial photography was carried out on the Oxfordshire gravels by Major Allen in the 1930s, and Edwin Thurlow Leeds, based at the Ashmolean Museum, carried out excavations at Sutton Courtenay, identifying Anglo-Saxon settlement in the 1920s, and at Abingdon, identifying a major early Anglo-Saxon cemetery (Leeds 1923, 1927, 1947; Leeds 1936).