Interim Guidelines for Hospital Response to Mass Casualties from a Radiological Incident December 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basics of Radiation Radiation Safety Orientation Open Source Booklet 1 (June 1, 2018)

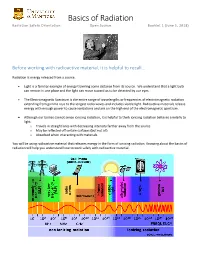

Basics of Radiation Radiation Safety Orientation Open Source Booklet 1 (June 1, 2018) Before working with radioactive material, it is helpful to recall… Radiation is energy released from a source. • Light is a familiar example of energy traveling some distance from its source. We understand that a light bulb can remain in one place and the light can move toward us to be detected by our eyes. • The Electromagnetic Spectrum is the entire range of wavelengths or frequencies of electromagnetic radiation extending from gamma rays to the longest radio waves and includes visible light. Radioactive materials release energy with enough power to cause ionizations and are on the high end of the electromagnetic spectrum. • Although our bodies cannot sense ionizing radiation, it is helpful to think ionizing radiation behaves similarly to light. o Travels in straight lines with decreasing intensity farther away from the source o May be reflected off certain surfaces (but not all) o Absorbed when interacting with materials You will be using radioactive material that releases energy in the form of ionizing radiation. Knowing about the basics of radiation will help you understand how to work safely with radioactive material. What is “ionizing radiation”? • Ionizing radiation is energy with enough power to remove tightly bound electrons from the orbit of an atom, causing the atom to become charged or ionized. • The charged atoms can damage the internal structures of living cells. The material near the charged atom absorbs the energy causing chemical bonds to break. Are all radioactive materials the same? No, not all radioactive materials are the same. -

NATO and NATO-Russia Nuclear Terms and Definitions

NATO/RUSSIA UNCLASSIFIED PART 1 PART 1 Nuclear Terms and Definitions in English APPENDIX 1 NATO and NATO-Russia Nuclear Terms and Definitions APPENDIX 2 Non-NATO Nuclear Terms and Definitions APPENDIX 3 Definitions of Nuclear Forces NATO/RUSSIA UNCLASSIFIED 1-1 2007 NATO/RUSSIA UNCLASSIFIED PART 1 NATO and NATO-Russia Nuclear Terms and Definitions APPENDIX 1 Source References: AAP-6 : NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions AAP-21 : NATO Glossary of NBC Terms and Definitions CP&MT : NATO-Russia Glossary of Contemporary Political and Military Terms A active decontamination alpha particle A nuclear particle emitted by heavy radionuclides in the process of The employment of chemical, biological or mechanical processes decay. Alpha particles have a range of a few centimetres in air and to remove or neutralise chemical, biological or radioactive will not penetrate clothing or the unbroken skin but inhalation or materials. (AAP-21). ingestion will result in an enduring hazard to health (AAP-21). décontamination active активное обеззараживание particule alpha альфа-частицы active material antimissile system Material, such as plutonium and certain isotopes of uranium, The basic armament of missile defence systems, designed to which is capable of supporting a fission chain reaction (AAP-6). destroy ballistic and cruise missiles and their warheads. It includes See also fissile material. antimissile missiles, launchers, automated detection and matière fissile радиоактивное вещество identification, antimissile missile tracking and guidance, and main command posts with a range of computer and communications acute radiation dose equipment. They can be subdivided into short, medium and long- The total ionising radiation dose received at one time and over a range missile defence systems (CP&MT). -

Estimation of the Collective Effective Dose to the Population from Medical X-Ray Examinations in Finland

Estimation of the collective effective dose to the population from medical x-ray examinations in Finland Petra Tenkanen-Rautakoskia, Hannu Järvinena, Ritva Blya aRadiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (STUK), PL 14, 00880 Helsinki, Finland Abstract. The collective effective dose to the population from all x-ray examinations in Finland in 2005 was estimated. The numbers of x-ray examinations were collected by a questionnaire to the health care units (response rate 100 %). The effective doses in plain radiography were calculated using a Monte Carlo based program (PCXMC), as average values for selected health care units. For computed tomography (CT), weighted dose length product (DLPw) in a standard phantom was measured for routine CT protocols of four body regions, for 80 % of CT scanners including all types. The effective doses were calculated from DPLw values using published conversion factors. For contrast-enhanced radiology and interventional radiology, the effective dose was estimated mainly by using published DAP values and conversion factors for given body regions. About 733 examinations per 1000 inhabitants (excluding dental) were made in 2005, slightly less than in 2000. The proportions of plain radiography, computed tomography, contrast-enhanced radiography and interventional procedures were about 92, 7, 1 and 1 %, respectively. From 2000, the frequencies (number of examinations per 1000 inhabitants) of plain radiography and contrast-enhanced radiography have decreased about 8 and 33 %, respectively, while the frequencies of CT and interventional radiology have increased about 28 and 38 %, respectively. The population dose from all x-ray examinations is about 0,43 mSv per person (in 1997 0,5 mSv). -

THE COLLECTIVE EFFECTIVE DOSE RESULTING from RADIATION EMITTED DURING the FIRST WEEKS of the FUKUSHIMA DAIICHI NUCLEAR ACCIDENT Matthew Mckinzie, Ph.D

THE COLLECTIVE EFFECTIVE DOSE RESULTING FROM RADIATION EMITTED DURING THE FIRST WEEKS OF THE FUKUSHIMA DAIICHI NUCLEAR ACCIDENT Matthew McKinzie, Ph.D. and Thomas B. Cochran, Ph.D., Natural Resources Defense Council April 10, 2011 The Magnitude 9.0 earthquake off Japan’s Pacific Coast, which was the initiating event for accidents at four of the six reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, occurred at 14:46 local time on March 11th. At 15:41 a tsunami hit the plant and a station blackout ensued. A reconstruction of the accident progression by Areva1 posited that the final option for cooling the reactors – the reactor core isolation pumps – failed just hours later in Unit 1 (at 16:36), failed in the early morning of March 13th in Unit 3 (at 02:44), and failed early in the afternoon of March 14th in Unit 2 (at 13:25). Radiological releases spiked beginning on March 15th and in the Areva analysis are attributed to the venting of the reactor pressure vessels, explosion in Unit 2, and – significantly – explosion and fire in Unit 4. Fuel had been discharged from the Unit 4 reactor core to the adjacent spent fuel pool on November 30, 2010, raising the possibility of a core melt “on fresh air.” The Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) has posted hourly dose rates by prefecture2 on its website. We do not currently know the geographic coordinates of these radiation monitoring sites. The English language versions of the hourly dose rate measurements by prefecture begin in table form at 17:00 on March 16th, and hourly dose rates are provided as charts3 beginning at 00:00 on March 14th. -

Individual and Collective Dose Limits and Radionuclide Release Limits

UNITED STATES NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON NUCLEAR WASTE WASHINGTON, D.C. 20555 April 29, 1991 r' Mr. Robert M. Bernero, Director Office of Nuclear Material Safety and Safeguards u.s. Nuclear Regulatory Commission Washington, DC 20555 Dear Mr. Bernero: SUBJECT: INDIVIDUAL AND COLLECTIVE DOSE LIMITS AND RADIONUCLIDE RELEASE LIMITS The Advisory Committee . on Nuclear waste has been developing comments, thoughts, and suggestions relative to individual and collective dose limits and radionuclide release limits. Since we understand that your staff is reviewing these same topics, we wanted to share our thoughts with you. In formulating these comments, we have had discussions with a number of people, including members of the NRC staff and Committee consultants. The Committee also had the benefit of the documents listed. Basic Definitions As a basic philosophy, individual dose limits are used to place restrictions on the risk to individual members of the public due to operations at a nuclear facility. If the limits have been properly established and compliance is observed, a regulatory agency can be confident that the associated risk to individual members of the pUblic is acceptable. Because the determination of the dose to individual members of the pUblic is difficult, the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) has developed the concept of the "critical group" and recommends that it be used in assessing doses resulting from environmental releases. As defined by the ICRP, a critical group is a relatively homogeneous group of people whose location and living habits are such that they receive the highest doses as a result of radio nuclide releases. -

Radiation Basics

Environmental Impact Statement for Remediation of Area IV \'- f Susana Field Laboratory .A . &at is radiation? Ra - -.. - -. - - . known as ionizing radiatios bScause it can produce charged.. particles (ions)..- in matter. .-- . 'I" . .. .. .. .- . - .- . -- . .-- - .. What is radioactivity? Radioactivity is produced by the process of radioactive atmi trying to become stable. Radiation is emitted in the process. In the United State! Radioactive radioactivity is measured in units of curies. Smaller fractions of the curie are the millicurie (111,000 curie), the microcurie (111,000,000 curie), and the picocurie (1/1,000,000 microcurie). Particle What is radioactive material? Radioactive material is any material containing unstable atoms that emit radiation. What are the four basic types of ionizing radiation? Aluminum Leadl Paper foil Concrete Adphaparticles-Alpha particles consist of two protons and two neutrons. They can travel only a few centimeters in air and can be stopped easily by a sheet of paper or by the skin's surface. Betaparticles-Beta articles are smaller and lighter than alpha particles and have the mass of a single electron. A high-energy beta particle can travel a few meters in the air. Beta particles can pass through a sheet of paper, but may be stopped by a thin sheet of aluminum foil or glass. Gamma rays-Gamma rays (and x-rays), unlike alpha or beta particles, are waves of pure energy. Gamma radiation is very penetrating and can travel several hundred feet in air. Gamma radiation requires a thick wall of concrete, lead, or steel to stop it. Neutrons-A neutron is an atomic particle that has about one-quarter the weight of an alpha particle. -

MIRD Pamphlet No. 22 - Radiobiology and Dosimetry of Alpha- Particle Emitters for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy

Alpha-Particle Emitter Dosimetry MIRD Pamphlet No. 22 - Radiobiology and Dosimetry of Alpha- Particle Emitters for Targeted Radionuclide Therapy George Sgouros1, John C. Roeske2, Michael R. McDevitt3, Stig Palm4, Barry J. Allen5, Darrell R. Fisher6, A. Bertrand Brill7, Hong Song1, Roger W. Howell8, Gamal Akabani9 1Radiology and Radiological Science, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore MD 2Radiation Oncology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood IL 3Medicine and Radiology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York NY 4International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Austria 5Centre for Experimental Radiation Oncology, St. George Cancer Centre, Kagarah, Australia 6Radioisotopes Program, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland WA 7Department of Radiology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville TN 8Division of Radiation Research, Department of Radiology, New Jersey Medical School, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark NJ 9Food and Drug Administration, Rockville MD In collaboration with the SNM MIRD Committee: Wesley E. Bolch, A Bertrand Brill, Darrell R. Fisher, Roger W. Howell, Ruby F. Meredith, George Sgouros (Chairman), Barry W. Wessels, Pat B. Zanzonico Correspondence and reprint requests to: George Sgouros, Ph.D. Department of Radiology and Radiological Science CRB II 4M61 / 1550 Orleans St Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine Baltimore MD 21231 410 614 0116 (voice); 413 487-3753 (FAX) [email protected] (e-mail) - 1 - Alpha-Particle Emitter Dosimetry INDEX A B S T R A C T......................................................................................................................... -

General Terms for Radiation Studies: Dose Reconstruction Epidemiology Risk Assessment 1999

General Terms for Radiation Studies: Dose Reconstruction Epidemiology Risk Assessment 1999 Absorbed dose (A measure of potential damage to tissue): The Bias In epidemiology, this term does not refer to an opinion or amount of energy deposited by ionizing radiation in a unit mass point of view. Bias is the result of some systematic flaw in the of tissue. Expressed in units of joule per kilogram (J/kg), which design of a study, the collection of data, or in the analysis of is given the special name Agray@ (Gy). The traditional unit of data. Bias is not a chance occurrence. absorbed dose is the rad (100 rad equal 1 Gy). Biological plausibility When study results are credible and Alpha particle (ionizing radiation): A particle emitted from the believable in terms of current scientific biological knowledge. nucleus of some radioactive atoms when they decay. An alpha Birth defect An abnormality of structure, function or body particle is essentially a helium atom nucleus. It generally carries metabolism present at birth that may result in a physical and (or) more energy than gamma or beta radiation, and deposits that mental disability or is fatal. energy very quickly while passing through tissue. Alpha particles cannot penetrate the outer, dead layer of skin. Cancer A collective term for malignant tumors. (See “tumor,” Therefore, they do not cause damage to living tissue when and “malignant”). outside the body. When inhaled or ingested, however, alpha particles are especially damaging because they transfer relatively Carcinogen An agent or substance that can cause cancer. large amounts of ionizing energy to living cells. -

Radiation Glossary

Radiation Glossary Activity The rate of disintegration (transformation) or decay of radioactive material. The units of activity are Curie (Ci) and the Becquerel (Bq). Agreement State Any state with which the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission has entered into an effective agreement under subsection 274b. of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, as amended. Under the agreement, the state regulates the use of by-product, source, and small quantities of special nuclear material within said state. Airborne Radioactive Material Radioactive material dispersed in the air in the form of dusts, fumes, particulates, mists, vapors, or gases. ALARA Acronym for "As Low As Reasonably Achievable". Making every reasonable effort to maintain exposures to ionizing radiation as far below the dose limits as practical, consistent with the purpose for which the licensed activity is undertaken. It takes into account the state of technology, the economics of improvements in relation to state of technology, the economics of improvements in relation to benefits to the public health and safety, societal and socioeconomic considerations, and in relation to utilization of radioactive materials and licensed materials in the public interest. Alpha Particle A positively charged particle ejected spontaneously from the nuclei of some radioactive elements. It is identical to a helium nucleus, with a mass number of 4 and a charge of +2. Annual Limit on Intake (ALI) Annual intake of a given radionuclide by "Reference Man" which would result in either a committed effective dose equivalent of 5 rems or a committed dose equivalent of 50 rems to an organ or tissue. Attenuation The process by which radiation is reduced in intensity when passing through some material. -

Exposure Data

X-RADIATION AND γ-RADIATION 1. Exposure data 1.1 Occurrence 1.1.1 X-radiation X-rays are electromagnetic waves in the spectral range between the shortest ultraviolet (down to a few tens of electron volts) and γ-radiation (up to a few tens of mega electron volts) (see Figure 2, Overall introduction). The term γ-radiation is usually restricted to radiation originating from the atomic nucleus and from particle annihilation, while the term X-radiation covers photon emissions from electron shells. X-rays are emitted when charged particles are accelerated or decelerated, during transitions of electrons from the outer regions of the atomic shell to regions closer to the nucleus, and as bremsstrahlung, i.e. radiation produced when an electron collides with, or is deflected by, a positively charged nucleus. The resulting line spectra are characteristic for the corresponding element, whereas bremsstrahlung shows a conti- nuous spectrum with a steep border at the shortest wavelengths. Interaction of X-rays with matter is described by the Compton scattering and photoelectric effect and their resulting ionizing potentials, which lead to significant chemical and biological effects. Ions and radicals are produced in tissues from single photons and cause degradation and changes in covalent binding in macromolecules such as DNA. In other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, below the spectra of ultraviolet and visible light, the single photon energies are too low to cause genotoxic × –μ⋅d effects. The intensity (I) of X-rays inside matter decreases according to I = I0 10 , where d is the depth and μ a coefficient specific to the interacting material and the corresponding wavelength. -

A Critical Review of Alpha Radionuclide Therapy—How to Deal with Recoiling Daughters?

Pharmaceuticals 2015, 8, 321-336; doi:10.3390/ph8020321 OPEN ACCESS pharmaceuticals ISSN 1424-8247 www.mdpi.com/journal/pharmaceuticals Review A Critical Review of Alpha Radionuclide Therapy—How to Deal with Recoiling Daughters? Robin M. de Kruijff, Hubert T. Wolterbeek and Antonia G. Denkova * Radiation Science and Technology, Delft University of Technology, Mekelweg 15, 2629 JB Delft, The Netherlands; E-Mails: [email protected] (R.M.K.); [email protected] (H.T.W.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +31-15-27-84471. Academic Editor: Svend Borup Jensen Received: 15 April 2015 / Accepted: 1 June 2015 / Published: 10 June 2015 Abstract: This review presents an overview of the successes and challenges currently faced in alpha radionuclide therapy. Alpha particles have an advantage in killing tumour cells as compared to beta or gamma radiation due to their short penetration depth and high linear energy transfer (LET). Touching briefly on the clinical successes of radionuclides emitting only one alpha particle, the main focus of this article lies on those alpha-emitting radionuclides with multiple alpha-emitting daughters in their decay chain. While having the advantage of longer half-lives, the recoiled daughters of radionuclides like 224Ra (radium), 223Ra, and 225Ac (actinium) can do significant damage to healthy tissue when not retained at the tumour site. Three different approaches to deal with this problem are discussed: encapsulation in a nano-carrier, fast uptake of the alpha emitting radionuclides in tumour cells, and local administration. Each approach has been shown to have its advantages and disadvantages, but when larger activities need to be used clinically, nano-carriers appear to be the most promising solution for reducing toxic effects, provided there is no accumulation in healthy tissue. -

Radiological Information

RADIOLOGICAL INFORMATION Frequently Asked Questions Radiation Information A. Radiation Basics 1. What is radiation? Radiation is a form of energy. It is all around us. It is a type of energy in the form of particles or electromagnetic rays that are given off by atoms. The type of radiation we are concerned with, during radiation incidents, is “ionizing radiation”. Radiation is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and invisible. 2. What is radioactivity? It is the process of emission of radiation from a material. 3. What is ionizing radiation? It is a type of radiation that has enough energy to break chemical bonds (knocking out electrons). 4. What is non-ionizing radiation? Non-ionizing radiation is a type of radiation that has a long wavelength. Long wavelength radiations do not have enough energy to "ionize" materials (knock out electrons). Some types of non-ionizing radiation sources include radio waves, microwaves produced by cellular phones, microwaves from microwave ovens and radiation given off by television sets. 5. What types of ionizing radiation are there? Three different kinds of ionizing radiation are emitted from radioactive materials: alpha (helium nuclei); beta (usually electrons); x-rays; and gamma (high energy, short wave length light). • Alpha particles stop in a few inches of air, or a thin sheet of cloth or even paper. Alpha emitting materials pose serious health dangers primarily if they are inhaled. • Beta particles are easily stopped by aluminum foil or human skin. Unless Beta particles are ingested or inhaled they usually pose little danger to people. • Gamma photons/rays and x-rays are very penetrating.