MDBA Indigenous SIA Final Oct 071010X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Founding of Aboriginal History and the Forming of Aboriginal History

The founding of Aboriginal History and the forming of Aboriginal history Bain Attwood Nearly 40 years ago an important historical project was launched at The Australian National University (ANU). It came to be called Aboriginal history. It was the name of both a periodical and a historiographical movement. In this article I seek to provide a comprehensive account of the founding of the former and to trace something of the formation of the latter.1 Aboriginal history first began to be formed in the closing months of 1975 when a small group of historically-minded white scholars at ANU agreed to found what they described as a journal of Aboriginal History. At that time, the term, let alone the concept of Aboriginal history, was a novel one. The planners of this academic journal seem to have been among the first to use the phrase in its discursive sense when they suggested that it ‘should serve as a publications outlet in the field of Aboriginal history’.2 Significantly, the term was adopted in the public realm at much the same time. The reports of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (the Pigott Report) and the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, which were the outcome of an inquiry commissioned by the Whitlam Labor Government in order to articulate and give expression to a new Australian nationalism by championing a past that was indigenous to the Australian continent, both used the term.3 As 1 I wish to thank Niel Gunson, Bob Reece and James Urry for allowing me to view some of their personal -

Australian Aboriginal Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australian Aboriginal Art Patrick Hutchings To attack one’s neighbours, to pass or to crush and subdue more remote peoples without provocation and solely for the thirst for dominion—what is one to call it but brigandage on a grand scale?1 The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo, IV Ch 6 ‘The natives are extremely fond of painting and often sit hours by me when at work’ 2 Thomas Watling The Australians and the British began their relationship by ‘dancing together’, so writes Inge Clendinnen in her multi-voiced Dancing With Strangers 3 which weaves contemporary narratives of Sydney Cove in 1788. The event of dancing is witnessed to by a watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley, ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales March 1788’, which is reproduced by Clendinnen as both a plate and a dustcover.4 By ‘The Australians’ Clendinnen means the Aboriginal pop- ulation. But, of course, Aboriginality is not an Aboriginal concept but an Imperial one. As Sonja Kurtzer writes: ‘The concept of Aboriginality did not even exist before the coming of the European’.5 And as for the terra nullius to which the British came, it was always a legal fiction. All this taken in, one sees why Clendinnen calls the First People ‘The Australians’, leaving most of those with the current passport very much Second People. But: winner has taken, almost, all. The Eddie Mabo case6 exploded terra nullius, but most of the ‘nobody’s land’ now still belongs to the Second People. -

THE BIDGEE BULLETIN Quarterly Newsletter of the Murrumbidgee Monitoring Program

M A R C H 2 0 2 0 I S S U E 3 THE BIDGEE BULLETIN Quarterly Newsletter of the Murrumbidgee Monitoring Program WATERING OUTCOMES Welcome to Issue 3 of The Bidgee Bulletin. The field monitoring season is now complete, with As in previous years Commonwealth environmental water the last of the four wetland surveys conducted is being used to support aquatic plants and animals in the over the last two weeks of March. In this issue Murrumbidgee Selected Area. This year environmental we review the highlights of the season and water was largely used to target floodplains and wetlands summarise the outcomes from Commonwealth to improve water quality, support populations of water environmental watering actions during the 2019- dependent plants and animals, maintain frog populations 20 water year. We also introduce our Chief and create breeding opportunities for threatened species Twitcher from the NSW DPIE, Dr Jennifer including the southern bell frog and Australasian bittern. Spencer. Continued dry conditions in Spring 2019 meant that The Bidgee Bulletin is a quarterly newsletter environmental water needed to be carefully managed and designed to provide updates on our progress as focused on high priority outcomes. These included we monitor the ecological outcomes of maintaining critical refuge habitats - Wagourah Lagoon, Commonwealth environmental water flows in the Yarradda Lagoon, Telephone Creek and Tala Creek. Murrumbidgee Selected Area. The 2019-2022 Maintenance of these wetland habitats is important for program builds on the previous five year native fish and turtles, and the Murrumbidgee refuge sites monitoring period (2014-2019) and uses many continue to support high native fish diversity with large of the same methods. -

NAIDOC Week 2021

TEACHER GUIDE YEARS F TO 10 NAIDOC Week 2021 Warning – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers and students are advised that this curriculumresource may contain images, voices or names of deceased people. Glossary Terms that may need to be introduced to students prior to teaching the resource: ceded: to hand over or give up something, such as land, to someone else. First Nations people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. NAIDOC: (acronym) National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee. NAIDOC Week: a nationally recognised week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. All Australians are invited to participate. sovereignty: supreme authority and independent power claimed or possessed by a community or state to govern itself or another state. Resource overview Introduction to NAIDOC Week – A history of protest and celebration NAIDOC Week is usually celebrated in the first full week of July. It’s a week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of First Nations people. Although NAIDOC Week falls in the mid-year school holidays, the aim of each theme isn’t limited to those set dates. Schools are encouraged to recognise and celebrate NAIDOC Week at any time throughout the year to ensure this important event isn’t overlooked. Themes can be incorporated as part of school life and the school curriculum. NAIDOC stands for ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’, the committee responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week. Its acronym has now become the name of the week. NAIDOC Week has a long history beginning with the human rights movement for First Nations Peoples in the 1920s. -

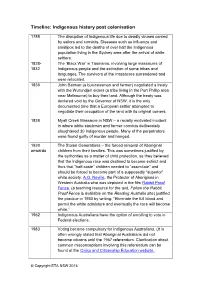

Indigenous History Post Colonisation

Timeline: Indigenous history post colonisation 1788 The disruption of Indigenous life due to deadly viruses carried by sailors and convicts. Diseases such as influenza and smallpox led to the deaths of over half the Indigenous population living in the Sydney area after the arrival of white settlers. 1828- The ‘Black War’ in Tasmania, involving large massacres of 1832 Indigenous people and the extinction of some tribes and languages. The survivors of the massacres surrendered and were relocated. 1835 John Batman (a businessman and farmer) negotiated a treaty with the Wurundjeri elders (a tribe living in the Port Phillip area near Melbourne) to buy their land. Although the treaty was declared void by the Governor of NSW, it is the only documented time that a European settler attempted to negotiate their occupation of the land with its original owners. 1838 Myall Creek Massacre in NSW – a racially motivated incident in where white stockmen and former convicts deliberately slaughtered 30 Indigenous people. Many of the perpetrators were found guilty of murder and hanged. 1930 The Stolen Generations – the forced removal of Aboriginal onwards children from their families. This was sometimes justified by the authorities as a matter of child protection, as they believed that the Indigenous race was destined to become extinct and thus that “half-caste” children needed to “assimilate” and should be forced to become part of a supposedly “superior” white society. A.O. Neville, the Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia who was depicted in the film Rabbit Proof Fence, (a teaching resource for the text, Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence is available on the Reading Australia site) justified the practice in 1930 by writing: “Eliminate the full blood and permit the white admixture and eventually the race will become white.” 1962 Indigenous Australians have the option of enrolling to vote in Federal elections. -

Register of Committees 2020/2021

REGISTER OF COMMITTEES 2020/2021 Tamworth Regional Council Register contains the committees that have Council representation including: Council Special Purpose Committees, Council Working Groups, External Boards, Committees, Working Groups and Organisations External Boards, Committees, Working Group and Organisations for Council Staff Only. Tamworth Regional Council Ray Walsh House 437 Peel Street PO Box555 TAMWORTH NSW 2340 02 6767 5555 02 6767 5499 Tamworth Regional Council Register of Council Committees 2020/2021 1. CONTENTS 1. COUNCIL SPECIAL PURPOSE COMMITTEES ........................................................... 4 1.1. Annual Donations Programme ................................................................................... 4 1.2. General Managers Performance Review Panel ......................................................... 5 1.3. Murrami Poultry Broiler Farm Development Community Liaison Committee .............. 6 1.4. Tamworth Regional Floodplain Management Committee .......................................... 7 1.5. Tamworth Regional Local Traffic Committee ............................................................. 8 1.6. Tamworth Regional Rural Fire Service Liaison Committee ........................................ 9 1.7. Tamworth Sports Dome Committee ......................................................................... 10 2. COUNCIL WORKING GROUPS .................................................................................. 11 2.1. Audit, Risk and Improvement Committee ................................................................ -

Upper North West, REGIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Upper North West REGIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 2018–2022 VISION Maximise the opportunities provided by the region’s engine industries and wealth of natural assets while maintaining the quality of the environment and quality of life for a growing population. Preface The NSW Government has assisted local councils Regional Economic Development Strategies are and their communities to develop 37 Regional viewed as the frst stage of a process that will Economic Development Strategies across regional assist those with an interest in the economic NSW. Each strategy is designed around one or development of the region, particularly councils, more local government areas that form a functional communities and local businesses, in planning a economic region as defned by economic data region’s future economic activities. These strategies and community input. While the strategies have provide a vehicle for engaging the community in a been developed using a consistent methodology, ‘conversation’ about regional needs and priorities, each is a product of detailed data analysis and assist in bringing together key stakeholders and local community consultation to ensure ownership mobilising resources, and in so doing, can facilitate through a ‘bottom-up’ process: it sets out a vision faster access to dedicated NSW Government for the region, the strategies and early-stage actions funding, such as the Growing Local Economies required to achieve the vision. Fund, as well helping to capitalise on other Regional Economic Development Strategies economic opportunities. articulate a framework for identifying actions The Upper North West Regional Economic that are crucial to achieving the regional vision. Development Strategy is the culmination of Projects listed in a strategy should be viewed as collaboration between the Moree Plains Shire, example projects that have emerged from the initial Narrabri Shire, Gwydir Shire and Inverell Shire application of the framework. -

Balranald Mineral Sands Project Social Assessment

Appendix O Social Assessment www.emgamm.com www.iluka.com Balranald Mineral Sands Project Social Assessment Prepared for Iluka Resources Limited May 2015 www.emgamm.com www.iluka.com BalranaldMineralSandsProject SocialAssessment IlukaTrimReferenceNo:1305935 PreparedforIlukaResourcesLtd|5May2015 GroundFloor,Suite01,20ChandosStreet StLeonards,NSW,2065 T+61 2 94939500 F+61294939599 [email protected] emgamm.com BalranaldMineralSandsProject SocialAssessmentFinal ReportJ12011RP1|PreparedforIlukaResourcesLtd|5May2015 Preparedby BrettMcLennan Approvedby KateCox Position Director Position AssociateEnvironmentalScientist Signature Signature Date 5May2015 Date 5May2015 This report has been prepared in accordance with the brief provided by the client and has relied upon the information collected at the time and under the conditions specified in the report. All findings, conclusions or recommendations contained in the report are based on the aforementioned circumstances. The report is for the use of the client and no responsibilitywillbetakenforitsusebyotherparties.Theclientmay,atitsdiscretion,usethereporttoinformregulators andthepublic. © Reproduction of this report for educational or other noncommercial purposes is authorised without prior written permissionfromEMMprovidedthesourceisfullyacknowledged.Reproductionofthisreportforresaleorothercommercial purposesisprohibitedwithoutEMM’spriorwrittenpermission. DocumentControl Version Date Preparedby Reviewedby 1 27October2014 BrettMcLennan KateCox 2 17February2015 BrettMcLennan R 3 15March2015 -

Murrumbidgee Selected Area Monitoring, Evaluation and Research Plan

Murrumbidgee Selected Area Monitoring, Evaluation and Research Plan 2019 2019 – 2022 Prepared by: Wassens, Sa., Michael, D.R a., Spencer, Jc., Thiem, Jd., Kobayashi, Tc., Bino, Gb., Thomas, Rc., Brandis, Kb., Hall, Aa and Amos, C a, c. a Institute for Land, Water and Society. Charles Sturt University, PO Box 789, Albury, NSW 2640 b Centre for Ecosystem Science, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, 2052 c Water, Wetlands & Coasts Science Branch, NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, PO Box A290, Sydney South, NSW 1232 d NSW Trade and Investment Narrandera Fisheries Centre, PO Box 182, Narrandera NSW 2700 This MER Plan was commissioned and funded by Commonwealth Environmental Water Office with additional in-kind support from Charles Sturt University, University of NSW, NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, NSW Department of Primary Industries Copyright © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2019 Murrumbidgee Monitoring, Evaluation and Research Plan is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons By Attribution 3.0 Australia licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ This report should be attributed as ‘Murrumbidgee Monitoring, Evaluation and Research Plan Commonwealth of Australia 2019’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright. Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister of the Environment. -

Review of State Conservation Areas

Review of State Conservation Areas Report of the first five-year review of State Conservation Areas under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 November 2008 Cover photos (clockwise from left): Trial Bay Goal, Arakoon SCA (DECC); Glenrock SCA (B. Peters, DECC); Banksia, Bent Basin SCA (M. Lauder, DECC); Glenrock SCA (B. Peters, DECC). © Copyright State of NSW and Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW. The Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW and State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced for educational or non-commercial purposes in whole or in part, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. Published by: Department of Environment and Climate Change 59–61 Goulburn Street PO Box A290 Sydney South 1232 Ph: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Ph: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Ph: 1300 361 967 (national parks information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 978-1-74122-981-3 DECC 2008/516 November 2008 Printed on recycled paper Contents Minister’s Foreword iii Part 1 – State Conservations Areas 1 State Conservation Areas 4 Exploration and mining in NSW 6 History and current trends 6 Titles 7 Assessments 7 Compliance and rehabilitation 8 Renewals 8 Exploration and mining in State Conservation Areas 9 The five-year review 10 Purpose of the review 10 -

Australian Aboriginal Oral Traditions

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace Oral Tradition 1/2 (1986): 231-71 Australian Aboriginal Oral Traditions Margaret Clunies Ross 1. Aboriginal Oral Traditions A History of Research and Scholarship1 The makers of Australian songs, or of the combined songs and dances, are the poets, or bards, of the tribes, and are held in great esteem. Their names are known in the neighboring tribes, and their songs are carried from tribe to tribe, until the very meaning of the words is lost, as well as the original source of the song. It is hard to say how far and how long such a song may travel in the course of time over the Australian continent. (Howitt 1904:414) In 1988 non-Aboriginal Australians will celebrate two hundred years’ occupation of a country which had previously been home to an Aboriginal population of about 300,000 people. They probably spoke more than two hundred different languages and most individuals were multilingual (Dixon 1980). They had a rich culture, whose traditions were centrally concerned with the celebration of three basic types of religious ritual-rites of fertility, initiation, and death (Maddock 1982:105-57). In many parts of Australia, particularly in the south where white settlement was earliest and densest, Aboriginal traditional life has largely disappeared, although the memory of it has been passed down the generations. Nowadays all Aborigines, even in the most traditional parts of the north, such as Arnhem Land, are affected to a greater or lesser extent by the Australian version of Western culture, and must preserve their own traditions by a combination of holding strategies. -

Your Complete Guide to Broken Hill and The

YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO DESTINATION BROKEN HILL Mundi Mundi Plains Broken Hill 2 City Map 4–7 Getting There and Around 8 HistoriC Lustre 10 Explore & Discover 14 Take a Walk... 20 Arts & Culture 28 Eat & Drink 36 Silverton Places to Stay 42 Shopping 48 Silverton prospects 50 Corner Country 54 The Outback & National Parks 58 Touring RoutEs 66 Regional Map 80 Broken Hill is on Australian Living Desert State Park Central Standard Time so make Line of Lode Miners Memorial sure you adjust your clocks to suit. « Have a safe and happy journey! Your feedback about this guide is encouraged. Every endeavour has been made to ensure that the details appearing in this publication are correct at the time of printing, but we can accept no responsibility for inaccuracies. Photography has been provided by Broken Hill City Council, Destination NSW, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, Simon Bayliss, The Nomad Company, Silverton Photography Gallery and other contributors. This visitor guide has been designed by Gang Gang Graphics and produced by Pace Advertising Pty. Ltd. ABN 44 005 361 768 Tel 03 5273 4777 W pace.com.au E [email protected] Copyright 2020 Destination Broken Hill. 1 Looking out from the Line Declared Australia’s first heritage-listed of Lode Miners Memorial city in 2015, its physical and natural charm is compelling, but you’ll soon discover what the locals have always known – that Broken Hill’s greatest asset is its people. Its isolation in a breathtakingly spectacular, rugged and harsh terrain means people who live here are resilient and have a robust sense of community – they embrace life, are self-sufficient and make things happen, but Broken Hill’s unique they’ve always got time for each other and if you’re from Welcome to out of town, it doesn’t take long to be embraced in the blend of Aboriginal and city’s characteristic old-world hospitality.