The Nation of Islam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Wheel' (That Great Mother Plane)

‘The Wheel’ (That Great Mother Plane)—The Power of The Wheel to Destroy BY THE HONORABLE MINISTER LOUIS FARRAKHAN—PAGE 20 VOLUME 40 NUMBER 35 | JUNE 8, 2021 | U.S. $2.00 FINALCALLDIGITAL.COM | STORE.FINALCALL.COM | FINALCALL.COM THE BATTLE IN THE SKY The Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad Graphics: pixelsquid IS NEAR! For 90 years the Nation of Islam was mocked and ridiculed for its teaching on the Mother Plane and its aim, purpose. Now the gov’t admits these UFOs are real, vindicating what the Most Honorable Elijah Muhammad and the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan have warned of and prophesied. SPECIAL COVERAGE PAGES 3, 19, 20 2 THE FINAL CALL JUNE 8, 2021 AArrestsrrests mmadeade iinn sshootinghooting ooff yyoung,oung, BBlacklack aactivistctivist iinn UUKK bbutut qquestionsuestions rremainemain by Christopher iCha and Tariqah Shakir- Muhammad LONDON—In the after- math of the shooting of ac- tivist Sasha Johnson, arrests have been made but the young, Black woman continues fight- ing for her life. Ms. Johnson, a prominent leader of Britain’s first Black-led political party, was shot in the early hours of May 23, in South London. A 27-year-old Oxford graduate, Ms. Johnson, executive leader- ship member of the Taking the Initiative Party (TTIP), com- munity activist, and mother of three, sustained a non-fatal gunshot wound to her head. She’s currently in critical care at Kings College Hospital in nearby Camberwell after having undergone an operation and is in recovery. It is too ear- ly to know whether she has suf- fered any permanent damage. -

Engaged Surrender

one Engaged Surrender In 1991, when I ventured onto the grounds of Masjid Ummah, a mosque in Southern California, I was not new to African American Sunni Islam.1 In college, I had attempted to understand the “evolution” of the Muslim movement by examining the Nation of Islam’s journal Muhammad Speaks from the early 1960s through its transformation into the Muslim Journal, a Sunni Muslim weekly. What began my love of and fascination with the African American Sunni Muslim community is what I now see as an important but naive observation. In 1986, while riding on a bus in Chester, Pennsylvania, in ninety-nine degree weather, I observed a woman walking on the side- walk and wearing dark brown, polyester hijab and veil.2 She had two young children in tow, a boy and a girl, each with the proper, gendered head coverings: a skull cap for the boy and a scarf for the girl. I thought to myself, “Why would a woman in America choose not to be a femi- nist?” Or “Why would a woman in America choose not to have choices?” With respect to the first question, in the feminist literature of the 1970s, the psychological, symbolic, and neo-Marxist approaches to the study of gender asked why women are universally oppressed.3 The as- sumption of course is that in every society women are considered infe- 1 2/Engaged Surrender rior, an assumption that has been challenged in what is often described as “third wave feminism.”4 At the time I asked these questions, in the mid- and late 1980s, I was unfamiliar with the works of, for example, Chandra Mohanty, bell hooks, and Moraga and Anzaldua, who around the same time were articulating the importance of race, class, and nation in terms of women’s experiences with gender. -

Framing of Islam in the Early Cold War Era of Racialized Empire-Building

THE LESSER-EVILS PARADIGM FOR IMAGINING ISLAM: U.S. EXECUTIVE BRANCH (RE)FRAMING OF ISLAM IN THE EARLY COLD WAR ERA OF RACIALIZED EMPIRE-BUILDING by Sydney Porter Pasquinelli BA, Wayne State University, 2009 MA, Wake Forest University, 2011 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric & Communication University of Pittsburgh 2018 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Sydney Porter Pasquinelli It was defended on October 27, 2017 and approved by Paul Elliot Johnson Deepa Kumar John Lyne Shanara Rose Reid-Brinkley Dissertation Director: Gordon Roger Mitchell ii Copyright © by Sydney Porter Pasquinelli 2018 iii THE LESSER-EVILS PARADIGM FOR IMAGINING ISLAM: U.S. EXECUTIVE BRANCH (RE)FRAMING OF ISLAM IN THE EARLY COLD WAR ERA OF RACIALIZED EMPIRE-BUILDING Sydney Porter Pasquinelli, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2018 Rhetorical criticism of declassified United States executive branch intelligence documents produced by the Truman and Eisenhower administrations (1945-1961) illuminates how US agents (re)imagined Islam in this crucial yet understudied era of racialized empire-building. Two case studies help unravel characteristics of this dominant discourse: The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s attempt to delegitimize the Nation of Islam by characterizing its leadership and doctrine as violent, racist, and unorthodox; and the Central Intelligence Agency and State Department’s simultaneous effort to validate Islam and Islamism in the Middle East by positing them as ideological forces against communism and Arab Nationalism. Interactional and interdisciplinary consideration of archived rhetorical artifacts uncovers how motives to expand US empire, quell anti-imperial and anti-racist resistance, and advance early Cold War objectives encouraged executive agents to reframe Islam. -

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

Objects of Desire

Special Senior, End Of TheYear Issue Volume I • Number XVI Atlanta, Georgia May 2, 1994 FAREWELL CAU P2 May 2, 1994 The Panther AmeriCorps is the new domestic AmeriCorps... Peace Corps where thousands of young people will soon be getting the new National Service things done through service in exchange for help in financing movement that will their higher education or repaying their student loans. get things done. Starting this fall, thousands Watch for of AmeriCorps members will fan out across the nation to meet AmeriCorps, coming the needs of communities everywhere. And the kinds of soon to your community... things they will help get done can truly change America- and find out more things like immunizing our infants...tutoring our teenagers... by calling: k keeping our schools safe... restoring our natural resources 1-800-94-ACORPS. ...and securing more independent ^^Nives for our and our elderly. TDD 1-800-833-3722 Come hear L L Cool J at an AmeriCorps Campus Tour Rally for Change with A.U.C. Council of Presidents and other special guests. May 5,12 noon Morehouse Campus Green The Panther May 2, 1994 P3 Seniors Prepare The End Of The Road For Life After College By Johane Thomas AUC, and their experiences in the Contributing Writer classroom and their own personal experiences will carry over into the the work place. That special time of the year is here Eric Brown of Morehouse College again. As students prepare for gradua tion, they express concern over find plans to attend UCLA in the fall. As a ing jobs, respect in the workplace and Pre-Med major, Eric feels that his their experiences while attending learned skills will help him to suceed school here in the AUC. -

Muhammad, Sultan 1

Muhammad, Sultan 1 Sultan Muhammad Oral History Interview Thursday, February 28, 2019 Interviewer: This is an interview with Sultan Muhammad as part of the Chicago History Museum Muslim Oral History Project. The interview is being conducted on Thursday, February 28, 2019 at 3:02 pm at the Chicago History Museum. Sultan Muhammad is being interviewed by Mona Askar of the Chicago History Museum’s Studs Terkel Center for Oral History. Could you please state and spell your first and last name? Sultan Muhammad: My name is Sultan Muhammad. S-u-l-t-a-n Last name, Muhammad M-u-h-a-m-m-a-d Int: When and where were you born? SM: I was born here in Chicago in 1973. In the month of January 28th. Int: Could you please tell us about your parents, what they do for a living. Do you have any siblings? SM: My father, may blessings be on him, passed in 1990. He was also born here in Chicago. He is a grandson of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. He grew up in the Nation of Islam, working for his father, Jabir Herbert Muhammad who was the fight manager for Muhammad Ali and business manager of the Nation of Islam. Sultan Muhammad, my father, was also a pilot. He was the youngest black pilot in America at the time. Later he became an imam under Imam Warith Deen Mohammed after 1975. My mother, Jamima was born in Detroit. She is the daughter of Dorothy Rashana Hussain and Mustafa Hussain. Robert was his name before accepting Islam. -

Women of Color and the Struggle for Reproductive Justice IF/WHEN/HOW ISSUE BRIEF 2 WOMEN of COLOR and the STRUGGLE for REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE / IF/WHEN/HOW ISSUE BRIEF

Women of Color and the Struggle for Reproductive Justice IF/WHEN/HOW ISSUE BRIEF 2 WOMEN OF COLOR AND THE STRUGGLE FOR REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE / IF/WHEN/HOW ISSUE BRIEF Contents INTRODUCTION 3 AFRICAN-AMERICAN 3 NATIVE AMERICAN AND ALASKA NATIVE (INDIGENOUS) 5 ASIAN-AMERICAN AND PACIFIC ISLANDER (API) 5 LATIN@ (HISPANIC) 6 3 WOMEN OF COLOR AND THE STRUGGLE FOR REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE / IF/WHEN/HOW ISSUE BRIEF INTRODUCTION If/When/How recognizes that most law school courses are not applying an intersectional, reproductive justice lens to complex issues. To address this gap, our issue briefs and primers are designed to illustrate how law and policies disparately impact individuals and communities. If/When/How is committed to transforming legal education by providing students, instructors, and practitioners with the tools and support they need to utilize an intersectional approach. If/When/How, formerly Law Students for Reproductive Justice, trains, networks, and mobilizes law students and legal professionals to work within and beyond the legal system to champion reproductive justice. We work in partnership with local organizations and national movements to ensure all people have the ability to decide if, when, and how to create and sustain a family. AFRICAN-AMERICAN Due to continuing institutionalized racism and a history of reproductive oppression,1 many African-Americans today have limited access to adequate reproductive healthcare, higher rates of reproductive health issues, and are disproportionately impacted by restrictions on family health services.2 Low-income people are especially likely to lack control over their reproductive choices, and in 2011, 25.9% of African-Americans lived at or below the poverty level, compared to 10.6% of non-Hispanic white people.3 Pregnancy: • 67% of African-Americans’ pregnancies are unintended, compared to 40% for non-Hispanic, white people.4 • Ectopic pregnancy rates in African-Americans have declined more slowly than the national rate. -

Breaking Our Covenant with Death by the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan—Page 20

BREAKING OUR COVENANT WITH DEATH BY THE HONORABLE MINISTER LOUIS FARRAKHAN—PAGE 20 VOLUME 40 NUMBER 10 | DECEMBER 15, 2020 | U.S. $2.00 FINALCALLDIGITAL.COM | STORE.FINALCALL.COM | FINALCALL.COM BIG PHARMA, BIG MONEY, BIG FEARS Concerns about so-called vaccine cures driven by profits, too little proven research on safety, little talk of side-effects and no data on long term impact justify vows to reject Covid-19 vaccines say critics. SEE PAGES 3 AND 10 Graphic: istockphoto/grafissimo 2 THE FINAL CALL DECEMBER 15, 2020 ‘State-sponsored terrorism, police-sponsored terrorism,’ used to charge and target the leader of Black militia? by Brian E. Muhammad, Anisah Muhammad and J.A. Salaam The Final Call @TheFinalCall The leader of the Not F---king Around Coalition (NFAC), an all-Black militia that has been in the media over the last year was recently arrested on federal charges and later charged with state crimes by authorities in Kentucky. He is accused of pointing a weapon at federal agents and city po- lice offi cers. Activists and analysts say the charges refl ect longtime and ever-present attempts to control and target Blacks seen as “militant” and who claim the constitutional right to bear arms. John F. Johnson, also known as Grandmaster Jay, was charged Dec. 3 with assaulting and aiming an assault weapon at federal task force offi cers for the Federal Bureau of Inves- tigation, the U.S. Secret Service, and Louisville Metro Po- lice Department offi cers in early September. As WAVE-TV 3 in Louisville reported Dec. -

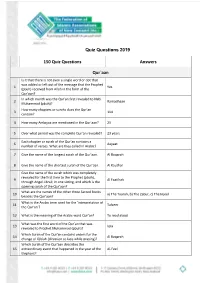

Quiz Questions 2019

Quiz Questions 2019 150 Quiz Questions Answers Qur`aan Is it that there is not even a single word or dot that was added or left out of the message that the Prophet 1 Yes (pbuh) received from Allah in the form of the Qur’aan? In which month was the Qur’an first revealed to Nabi 2 Ramadhaan Muhammad (pbuh)? How many chapters or surahs does the Qur’an 3 114 contain? 4 How many Ambiyaa are mentioned in the Qur’aan? 25 5 Over what period was the complete Qur’an revealed? 23 years Each chapter or surah of the Qur’an contains a 6 Aayaat number of verses. What are they called in Arabic? 7 Give the name of the longest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Baqarah 8 Give the name of the shortest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Kauthar Give the name of the surah which was completely revealed for the first time to the Prophet (pbuh), 9 Al Faatihah through Angel Jibrail, in one sitting, and which is the opening surah of the Qur’aan? What are the names of the other three Sacred Books 10 a) The Taurah, b) The Zabur, c) The Injeel besides the Qur’aan? What is the Arabic term used for the ‘interpretation of 11 Tafseer the Qur’an’? 12 What is the meaning of the Arabic word Qur’an? To read aloud What was the first word of the Qur’an that was 13 Iqra revealed to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh)? Which Surah of the Qur’an contains orders for the 14 Al Baqarah change of Qiblah (direction to face while praying)? Which Surah of the Qur’aan describes the 15 extraordinary event that happened in the year of the Al-Feel Elephant? 16 Which surah of the Qur’aan is named after a woman? Maryam -

Cultural Dakwah and Muslim Movements in the United States in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

JURNAL AQLAM – Journal of Islam and Plurality –Volume 5, Nomor 2, Juli – Desember 2020 CULTURAL DAKWAH AND MUSLIM MOVEMENTS IN THE UNITED STATES IN THE TWENTIETH AND TWENTY-FIRST CENTURIES Mark Woodward Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict Arizona State University [email protected] Abstract: There have been Muslims in what is now the United States since tens of thousands were brought as slaves in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Very few maintained their Muslim identities because the harsh conditions of slavery. Revitalization movements relying on Muslim symbolism emerged in the early 20th century. They were primarily concerned with the struggle against racism and oppression. The Moorish Science Temple of American and the Nation of Islam are the two most important of these movement. The haj was a transformative experience for Nation of Islam leaders Malcom X and Muhammad Ali. Realization that Islam is an inclusive faith that does not condone racism led both of them towards mainstream Sunni Islam and for Muhammad Ali to Sufi religious pluralism.1 Keywords: Nation of Islam, Moorish Science Temple, Revitalization Movement, Malcom X, Muhammad Ali Abstract: Sejarah Islam di Amerika sudah berakar sejak abad ke 18 dan awal 19, ketika belasan ribu budak dari Afrika dibawa ke wilayah yang sekarang bernama Amerika Serikat. Sangat sedikit di antara mereka yang mempertahankan identitasnya sebagai Muslim mengingat kondisi perbudakan yang sangat kejam dan tidak memungkinkan. Di awal abad 20, muncul-lah gerakan revitalisasi Islam. Utamanya, mereka berkonsentrasi pada gerakan perlawanan terhadap rasisme dan penindasan. The Moorish Science Temple of American dan the Nation of Islam adalah dua kelompok terpenting gerakan perlawanan tersebut. -

Is Abortionabortion “Black“Black Genocide”Genocide”

SISTERSONG WOMEN OF COLOR REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE COLLECTIVE C o l l e c t i v eVo i c e s VO L U M E 6 ISSUE 12 S u m m e r 2 0 1 1 IsIs AbortionAbortion “Black“Black Genocide”Genocide” AlliesAllies DefendingDefending BlackBlack WomenWomen UnshacklingUnshackling BlackBlack MotherhoodMotherhood ReproductiveReproductive VViolenceiolence aandnd BlackBlack WomenWomen WhyWhy II PrProvideovide AborAbortions:tions: AlchemAlchemyy ofof RaceRace,, Gender,Gender, andand HumanHuman RightsRights COLLECTIVEVOICES “The real power, as you and I well know, is collective. I can’t afford to be afraid of you, nor of me. If it takes head-on collisions, let’s do it. This polite timidity is killing us.” -Cherrie Moraga Publisher....................................................SisterSong Editor in Chief.........................................Loretta Ross Managing Editor.......................................Serena Garcia Creative Director....................................cscommunications Webmaster..............................................Dionne Turner CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Loretta Ross Laura Jimenez Heidi Williamson Dionne Turner Serena Garcia Charity Woods Monica Simpson Candace Cabbil Kathryn Joyce Willie J. Parker, MD, MPH, MSc Bani Hines Hudson Gina Brown Susan A. Cohen Laura L. Lovett Cherisse Scott From the Managing Editor, Serena Garcia: Please note in this issue of Collective Voices we have allowed our writers to maintain their own editorial integrity in how they use the terms, “Black”,“minority,” and the capitalization of Reproductive Justice. Send Inquiries to: [email protected] SEND STORY IDEAS TO: [email protected] SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective 1237 Ralph David Abernathy Blvd., SW Atlanta, GA 3011 404-756-2680 www.sistersong.net © All Rights Reserved 2 www.sistersong.net CV Message from the National Coordinator This special edition of Collective Voices is dedicated to women of color fighting race- and gender-specific anti-abortion legislation and billboards across the country. -

The Oakland Tribune (Oakland

The Oakland Tribune (Oakland, CA) August 17, 2004 Tuesday Muslim bakery leader confirmed dead BYLINE: By Harry Harris and Chauncey Bailey - STAFF WRITERS SECTION: MORE LOCAL NEWS LENGTH: 917 words OAKLAND -- A man found buried in a shallow grave last month in the Oakland hills was identified Monday as Waajid Aljawaad Bey, 51, president and chief executive officer of Your Black Muslim Bakery, police said. Police would not say how Bey, who assumed leadership of the bakery after the death of Yusuf Bey in September, had died. But Sgt. Bruce Brock said police are investigating the case "as a definite homicide." He would not say whether police think Bey was killed elsewhere before being buried at the site or was killed there and then buried. And while police are certain Bey was deliberately killed, Brock said despite a great deal of speculation, "we're not sure of a motive at this time." Some bakery insiders have feared that Bey's fate may be related to rivalries and a power play in the wake of Yusuf Bey's death from cancer in 2003. Although Bey never really discussed his Muslim activities with relatives, family members "are quite sure [the death] had something to do with him taking over" the organ ization, said a relative who asked not to be named. Bey's badly decomposed remains were discovered July 20 by a dog being walked by its owner on a fire trail that runs off the 8200 block of Fontaine Street near King Estates Middle School. Because of the circumstances surrounding the discovery of the body, it was classified as a homicide at the time, the city's 46th.