ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: PORTRAITURE and POLITICS in NEW YORK CITY, 1790-1825: STUART, VANDERLYN, TRUMBULL, and JARVIS Br

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York Painting Begins: Eighteenth-Century Portraits at the New-York Historical Society the New-York Historical Society Holds

New York Painting Begins: Eighteenth-Century Portraits at the New-York Historical Society The New-York Historical Society holds one of the nation’s premiere collections of eighteenth-century American portraits. During this formative century a small group of native-born painters and European émigrés created images that represent a broad swath of elite colonial New York society -- landowners and tradesmen, and later Revolutionaries and Loyalists -- while reflecting the area’s Dutch roots and its strong ties with England. In the past these paintings were valued for their insights into the lives of the sitters, and they include distinguished New Yorkers who played leading roles in its history. However, the focus here is placed on the paintings themselves and their own histories as domestic objects, often passed through generations of family members. They are encoded with social signals, conveyed through dress, pose, and background devices. Eighteenth-century viewers would have easily understood their meanings, but they are often unfamiliar to twenty-first century eyes. These works raise many questions, and given the sparse documentation from the period, not all of them can be definitively answered: why were these paintings made, and who were the artists who made them? How did they learn their craft? How were the paintings displayed? How has their appearance changed over time, and why? And how did they make their way to the Historical Society? The state of knowledge about these paintings has evolved over time, and continues to do so as new discoveries are made. This exhibition does not provide final answers, but presents what is currently known, and invites the viewer to share the sense of mystery and discovery that accompanies the study of these fascinating works. -

132 Portraits by Gilbert Stuart. in 1914

132 Portraits by Gilbert Stuart. PORTRAITS BY GILBERT STUART NOT INCLUDED IN PREVIOUS CATALOGUES OF HIS WORKS. BY MANTLE FIELDING. In 1914 the '' Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography" published a list of portraits painted by Gilbert Stuart, not mentioned in the "Life and Works of Gilbert Stuart" by George C. Mason. In 1920 this was followed in the same periodical by "Addenda and Corrections" to the first list, in all adding about one hundred and eighty portraits to the original pub- lication. This was followed in 1926 by the descriptive cata- logue of Stuart's work by the late Laurence Park, which noted many additions that up to that time had eluded the collectors' notice. In the last two years there have come to America a number of Stuart por- traits which were painted in England and Ireland and practically unknown here before. As a rule they differ in treatment and technique from his work in America and are reminiscent more or less of the English school. Many of these portraits lack some of the freedom and spirit of his American work having the more careful finish and texture of Eomney and Gainsborough. These paintings of Gil- bert Stuart made during his residence in England and Ireland possess a great charm like all the work of this talented painter and are now being much sought after by collectors in this country. No catalogue of the works of an early painter, how- ever, can be called complete or infallible and in the case of Gilbert Stuart there seems to be good reason to believe that there are still many of his portraits in Portraits by Gilbert Stuart. -

ESSSAR Masthead

EMPIRE PATRIOT Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution Descendants of America’s First Soldiers Volume 10 Issue 1 February 2008 Printed Four Times Yearly THE CONCLUSION OF . THE PHILADELPHIA CAMPAIGN In Summary: We started this journey several issues ago beginning with . LANDING AT THE HEAD OF ELK - Over 260 British ships arrived at Head of Elk, Maryland. Washington was ready. The trip took overly long, horses died by the hundreds. British General Howe was anxious to move on, but first he had to unload his massive armada. ON THE MARCH TO BRANDYWINE - Howe heads for Philadelphia. Washington blocks the path. On the way to their first engagement of 1777, Washington exposes himself to capture, Howe misses an opportunity, the rains fall, and everyone seems prepared for what happens next. THE BATTLE OF BRANDYWINE- The first battle in the campaign. Howe conceives and executes a daring 17 mile march catching Washington by surprise. The Continental Army is impressive, but the day belongs to the British. THE BATTLE OF THE CLOUDS Both armies were poised for another major engagement Five days after the Battle of Brandywine, a confrontation is rained out PAOLI MASSACRE Bloody bayonets in a midnight raid Mad” Anthony Wayne, assigned to attack the rear guard of the British army, is himself surprised in a “dirty” early morning raid. MARCH TO GERMANTOWN Washington prepares to win back the capital Congress flees Philadelphia as the British occupy the city amid chaos and fear. THE BATTLE OF GERMANTOWN The battle is fought in and around a mansion. For the first time the British retreat during battle, but fog and confusion turned the American advance around. -

"Amiable" Children of John and Sarah Livingston Jay by Louise V

The "Amiable" Children of John and Sarah Livingston Jay by Louise V. North © Columbia's Legacy: Friends and Enemies in the New Nation Conference at Columbia University and The New-York Historical Society, Dec. 10, 2004 Sarah Jay wrote her husband [Oct. 1801]: "I have been rendered very happy by the company of our dear children . I often, I shd. say daily, bless God for giving us such amiable Children. May they long be preserved a blessing to us & to the community." Who were these 'amiable' children, and what were they like? The happy marriage of John and Sarah Jay produced six children: Peter Augustus, born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, in 1776; Susan, born and died in Madrid after only a few weeks of life, in 1780; Maria, born in Madrid in 1782; Ann, born in Paris in 1783, William and Sarah Louisa, born in NYC in 1789 and 1792 respectively. As you can see by the birthplaces of these children, their parents played active parts on the stage of independence, doing what needed to be done, wherever it needed to be done, at the end of a colonial era and the birth of a new nation. John Jay held a greater variety of posts than any other Founding Father, posts he insisted he did not seek but felt it his duty to his country to assume. Sarah Livingston Jay, brought up in a political household, was a strong support to her husband, astutely networking with the movers and shakers of the time (as a look at her Invitation Lists of 1787–1788 shows). -

Deshler-Morris House

DESHLER-MORRIS HOUSE Part of Independence National Historical Park, Pennsylvania Sir William Howe YELLOW FEVER in the NATION'S CAPITAL DAVID DESHLER'S ELEGANT HOUSE In 1790 the Federal Government moved from New York to Philadelphia, in time for the final session of Germantown was 90 years in the making when the First Congress under the Constitution. To an David Deshler in 1772 chose an "airy, high situation, already overflowing commercial metropolis were added commanding an agreeable prospect of the adjoining the offices of Congress and the executive departments, country" for his new residence. The site lay in the while an expanding State government took whatever center of a straggling village whose German-speaking other space could be found. A colony of diplomats inhabitants combined farming with handicraft for a and assorted petitioners of Congress clustered around livelihood. They sold their produce in Philadelphia, the new center of government. but sent their linen, wool stockings, and leatherwork Late in the summer of 1793 yellow fever struck and to more distant markets. For decades the town put a "strange and melancholy . mask on the once had enjoyed a reputation conferred by the civilizing carefree face of a thriving city." Fortunately, Congress influence of Christopher Sower's German-language was out of session. The Supreme Court met for a press. single day in August and adjourned without trying a Germantown's comfortable upland location, not far case of importance. The executive branch stayed in from fast-growing Philadelphia, had long attracted town only through the first days of September. Secre families of means. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NATIONAL

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 10344019 (R«v. 646) "-T fP 1—— United States Department of the Interior '••: M ' n ,/ !_*, | jj National Park Service * i . National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NATIONAL This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for Individual properties or districts. See instructions In QuideHnea for Completing National Register Forma (National Register Bulletin 18). Complete each Item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable," For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategorles listed in the Instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name_______TCane. .Tnhn Tnne.c;. other names/site number "Breakwater" 2. Location street & number off southeast RT•\d of Hannonk Street N 4V not for publication City, town p^ r Harhnr N m vicinity state Maine code ME county Hancock code QQ9 zip code 04609 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property FY] private 2L building(s) Contributing Noncontributing I I public-local district 3___ ____ buildings I I public-State site ____ sites I I public-Federal structure ____ structures object ____ objects 0 Total Name of related multiple property listing: N/A Number of contributing resources previously listed In the National Register __0____ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ED nomination EH request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties In the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The Selected Papers of John Jay, 1760-1779 Volume 1 Index

The Selected Papers of John Jay, 1760-1779 Volume 1 Index References to earlier volumes are indicated by the volume number followed by a colon and page number (for example, 1:753). Achilles: references to, 323 Active (ship): case of, 297 Act of 18 April 1780: impact of, 70, 70n5 Act of 18 March 1780: defense of, by John Adams, 420; failure of, 494–95; impact of, 70, 70n5, 254, 256, 273n10, 293, 298n2, 328, 420; passage of, 59, 60n2, 96, 178, 179n1 Adams, John, 16, 223; attitude toward France, 255; and bills of exchange, 204n1, 273– 74n10, 369, 488n3, 666; and British peace overtures, 133, 778; charges against Gillon, 749; codes and ciphers used by, 7, 9, 11–12; and commercial regulations, 393; and commercial treaties, 645, 778; commissions to, 291n7, 466–67, 467–69, 502, 538, 641, 643, 645; consultation with, 681; correspondence of, 133, 176, 204, 393, 396, 458, 502, 660, 667, 668, 786n11; criticism of, 315, 612, 724; defends act of 18 March 1780, 420; documents sent to, 609, 610n2; and Dutch loans, 198, 291n7, 311, 382, 397, 425, 439, 677, 728n6; and enlargement of peace commission, 545n2; expenses of, 667, 687; French opposition to, 427n6; health of, 545; identified, 801; instructions to, 152, 469–71, 470–71n2, 502, 538, 641, 643, 657; letters from, 115–16, 117–18, 410–11, 640–41, 643–44, 695–96; letters to, 87–89, 141–43, 209–10, 397, 640, 657, 705–6; and marine prisoners, 536; and mediation proposals, 545, 545n2; as minister to England, 11; as minister to United Provinces, 169, 425; mission to Holland, 222, 290, 291n7, 300, 383, 439, -

The Bar of Rye Township, Westchester County, New York : an Historical and Biographical Record, 1660-1918

i Class JHlS ^ Book_t~Bii5_W_6 Edition limited to two hundred and fifty numbered copies, of which this is number .\ — The Bar of Rye Township Westchester County New York An Historical and Biographical Record 1660-1918 Arthur Russell Wilcox " There is properly no history, only biography." Emerson 8 Copyright, 191 BY ARTHUR R. WILCOX 2^ / i-o Ubc "ftnicftctbocftcr press, tKz\o aoch TO MY MOTHER THIS VOLUME IS LOVINGLY AND .VFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED — " Discourage litigation. Persuade your neighbors to compromise whenever you can. Point out to them how the nominal winner is often a real loser—in fees, expenses and waste of time. As a peacemaker, the lawyer has a superior opportunity of being a good man. Never stir up litigation. A worse man can scarcely be found than one who does this. Who can be more nearly a fiend than he who habitually overhauls the register of deeds in search of defects in titles, whereupon to stir up strife and put money in his pocket? A moral tone ought to be enforced in the profession which would drive such men out of it." Lincoln. Foreword This work, undertaken chiefly as a diversion, soon became a considerable task, but none the less a pleasant one. It is something which should have been done long since. The eminence of some of Rye's lawyers fully justifies it. It is far from complete. Indeed, at this late day it could not be otherwise; records have disappeared, recollections have become dim, and avenues of investigation are closed. Some names, perhaps, have been rescued from oblivion. -

H. Doc. 108-222

EIGHTEENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1823, TO MARCH 3, 1825 FIRST SESSION—December 1, 1823, to May 27, 1824 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1824, to March 3, 1825 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—DANIEL D. TOMPKINS, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOHN GAILLARD, 1 of South Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—CHARLES CUTTS, of New Hampshire SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MOUNTJOY BAYLY, of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—HENRY CLAY, 2 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—MATTHEW ST. CLAIR CLARKE, 3 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DUNN, of Maryland; JOHN O. DUNN, 4 of District of Columbia DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN BIRCH, of Maryland ALABAMA GEORGIA Waller Taylor, Vincennes SENATORS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES William R. King, Cahaba John Elliott, Sunbury Jonathan Jennings, Charlestown William Kelly, Huntsville Nicholas Ware, 8 Richmond John Test, Brookville REPRESENTATIVES Thomas W. Cobb, 9 Greensboro William Prince, 14 Princeton John McKee, Tuscaloosa REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Gabriel Moore, Huntsville Jacob Call, 15 Princeton George W. Owen, Claiborne Joel Abbot, Washington George Cary, Appling CONNECTICUT Thomas W. Cobb, 10 Greensboro KENTUCKY 11 SENATORS Richard H. Wilde, Augusta SENATORS James Lanman, Norwich Alfred Cuthbert, Eatonton Elijah Boardman, 5 Litchfield John Forsyth, Augusta Richard M. Johnson, Great Crossings Henry W. Edwards, 6 New Haven Edward F. Tattnall, Savannah Isham Talbot, Frankfort REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Wiley Thompson, Elberton REPRESENTATIVES Noyes Barber, Groton Samuel A. Foote, Cheshire ILLINOIS Richard A. Buckner, Greensburg Ansel Sterling, Sharon SENATORS Henry Clay, Lexington Ebenezer Stoddard, Woodstock Jesse B. Thomas, Edwardsville Robert P. Henry, Hopkinsville Gideon Tomlinson, Fairfield Ninian Edwards, 12 Edwardsville Francis Johnson, Bowling Green Lemuel Whitman, Farmington John McLean, 13 Shawneetown John T. -

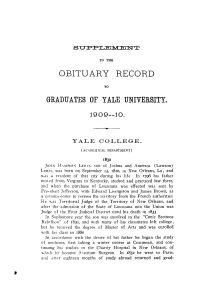

Obituary Record

S U TO THE OBITUARY RECORD TO GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVEESITY. 1909—10. YALE COLLEGE. (ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT) 1832 JOHN H \MPDFN LEWIS, son of Joshua and America (Lawson) Lewis, was born on September 14, 1810, m New Orleans, La, and was a resident of that city during his life In 1796 his father moved from Virginia to Kentucky, studied and practiced law there, and when the purchase of Louisiana was effected was sent by President Jefferson, with Edward Livingston and James Brown, as a commisMoner to receive the territory from the French authorities He was Territorial Judge of the Territory of New Orleans, and after the admission of the State of Louisiana into the Union was Judge of the First Judicial District until his death in 1833 In Sophomore year the son was involved in the "Conic Sections Rebellion" of 1830, and with many of his classmates left college, but he received the degree of Master of Arts and was enrolled with his class in 1880 In accordance with the desire of his father he began the study of medicine, first taking a winter course at Cincinnati, and con- tinuing his studies in the Charity Hospital in New Orleans, of which he became Assistant Surgeon In 1832 he went to Pans, and after eighteen months of study abroad returned and grad- YALE COLLEGE 1339 uated in 1836 with the first class from the Louisiana Medical College After having charge of a private infirmary for a time he again went abroad for further study In order to obtain the nec- essary diploma in arts and sciences he first studied in the Sorbonne after which he entered -

Portraits by Gilbert Stuart

PORTRAITS BY JUNE 29 TO AUGUST l • 1936 AT THE GALLERIES OF M. KNOEDLER & COMPANY NEWPORT RHODE ISLAND As A contribution to the Newport Tercentenary observation we feel that in no way can we make a more fitting offering than by holding an exhibition of paintings by Gilbert Stuart. Nar- ragansett was the birthplace and boyhood home of America's greatest artist and a Newport celebration would be grievously lacking which did not contain recognition of this. In arranging this important exhibition no effort has been made to give a chronological nor yet an historical survey of Stuart's portraits, rather have we aimed to show a collection of paintings which exemplifies the strength as well as the charm and grace of Stuart's work. This has required that we include portraits he painted in Ireland and England as well as those done in America. His place will always stand among the great portrait painters of the world. 1 GEORGE WASHINGTON Canvas, 25 x 30 inches. Painted, 1795. This portrait of George Washington, showing the right side of the face is known as the Vaughan type, so called for the owner of the first of the type, in contradistinction to the Athenaeum portrait depicting the left side of the face. Park catalogues fifteen of the Vaughan por traits and seventy-four of the Athenaeum portraits. "Philadelphia, 1795. Canvas, 30 x 25 inches. Bust, showing the right side of the face; powdered hair, black coat, white neckcloth and linen shirt ruffle. The background is plain and of a soft crimson and ma roon color. -

An Old Family; Or, the Setons of Scotland and America

[U AN OLD FAMILY OR The Setons of Scotland and America BY MONSIGNOR SETON (MEMBER OF THE NEW YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY) NEW YORK BRENTANOS 1899 Copyright, 1899, by ROBERT SETON, D. D. TO A DEAR AND HONORED KINSMAN Sir BRUCE-MAXWELL SETON of Abercorn, Baronet THIS RECORD OF SCOTTISH ANCESTORS AND AMERICAN COUSINS IS AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR Preface. The glories of our blood and state Are shadows, not substantial things. —Shirley. Gibbon says in his Autobiography: "A lively desire of knowing and recording our ancestors so generally prevails that it must depend on the influence of some common principle in the minds of men"; and I am strongly persuaded that a long line of distinguished and patriotic forefathers usually engenders a poiseful self-respect which is neither pride nor arrogance, nor a bit of medievalism, nor a superstition of dead ages. It is founded on the words of Scripture : Take care of a good name ; for this shall continue with thee more than a thousand treasures precious and great (Ecclesiasticus xli. 15). There is no civilized people, whether living under republi- can or monarchical institutions, but has some kind of aristoc- racy. It may take the form of birth, ot intellect, or of wealth; but it is there. Of these manifestations of inequality among men, the noblest is that of Mind, the most romantic that of Blood, the meanest that of Money. Therefore, while a man may have a decent regard for his lineage, he should avoid what- ever implies a contempt for others not so well born.