Family Business and Regional Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Economics: Understanding the Third Great Transition

REGIONAL ECONOMICS: UNDERSTANDING THE THIRD GREAT TRANSITION Paul Krugman September 2019 Memo to young economists: the transition from fiery upstart to old fuddy-duddy elder statesman sneaks up on you. One day, it seems, you’re trying to turn everything upside down; the next thing you know you’ve turned into one of those old guys whose response to any new idea is “It’s trivial, it’s wrong, and I said it in 1962.” Sure enough, in a couple of weeks I’m giving the luncheon keynote speech at a Boston Fed conference on America’s growing regional disparities, basically providing a break and maybe some inspiration in between presentations by real researchers. The brief talk doesn’t require a paper, and I am not someone who reads prepared speeches. But I thought I might take the occasion to write down a few thoughts on the subject. Basically, I want to make three points: 1. The regional divergence we’ve seen since around 1980 probably isn’t trivial or transient. Instead, it reflects a shift in the underlying logic of regional growth — the kind of shift that theories of economic geography predict will happen now and then, when the balance between forces of agglomeration and those of dispersion crosses a tipping point. 2. This isn’t the first time this kind of transition has happened. In fact, it’s the third such shift in the history of the U.S. economy, which went through earlier eras of both regional divergence and regional convergence. 3. There are pretty good although not ironclad arguments for “place-based” policies to limit regional divergence. -

Empadronamiento

Empadronamiento El empadronamiento es un requisito obligatorio para todas las personas que residen en un municipio. Es un derecho y un deber. Consiste en dar tus datos (nombre, apellidos y unadirección) en el ayuntamiento del municipio donde resides. Es gratuito. Debes identificarte con un documento oficial como el DNI, carnet de conducir o pasaporte. El empadronamiento confiere algunos derechos y deberes. Todas las personas inscritas en el padrón de un municipio constan como vecinas de éste y tienen derecho a la asistenciasanitaria pública y a la escolarización básica de sus hijos e hijas. También da el derecho a solicitar diversas ayudas sociales (ayudas de emegencia, renta básica, etc.) Las personas extranjeras que no tengan la residencia permanente, tienen que renovar su empadronamiento cada 2 años (si no lo hacen se les da de baja). Pasos a seguir El procedimiento puede variar de un ayuntamiento a otro. Documentación necesaria: Documento identificativo: pasaporte, carnet de identidad del país de origen, tarjeta de residencia… (Obligatorio) Documento que acredite el domicilio: escritura de compra, contrato de alquiler, autorización del titular del contrato de alquiler. En el caso de que la persona solicitante no conste en los documentos de compra o de alquiler de la vivienda se necesitará la autorización firmada del propietario de la vivienda y fotocopia de su DNI. ¿Cómo funciona un ayuntamiento? El ayuntamiento o corporación municipal es el órgano de administración de un municipio. Dependiendo del tamaño del ayuntamiento su estructura puede variar, pero como ejemplo ilustrativo se detalla a continuación el organigrama del Ayuntamiento de Tolosa. ORGANIGRAMA DEL AYUNTAMIENTO Pleno Poder decisorio Reuniones: 1 vez al mes (ordinarias). -

Doctor of Philosophy in Economics

ECO 6525 PUBLIC SECTOR ECONOMICS (3) Course Information Introduction to the public sector and the allocation of resources, emphasis on market failure and the economic role of government. ECO 6115 MICROECONOMICS I (3) (PR: ECO 6115) Microeconomic behavior of consumers, producers, and resource suppliers, price determination in output and factor markets, general ECO 6936 FORECASTING AND ECONOMIC TIME market equilibrium. (PR: ECO 3101, ECO 6405 or CI) SERIES (3) Study of time series econometrics estimation with applications to ECO 7116 MICROECONOMICS II (3) economic forecasting. (PR: ECO 6424) Topics in advanced microeconomic theory, including general equilibrium, welfare economics, intertemporal choice, uncertainty, ECO 6936 BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS (3) University of South Florida information, and game theory. (PR: ECO 6115) Survey of evidence on departures of economic agents from rationality. Topics include present-based preferences, reference College of Arts and Sciences ECO 6120 ECONOMIC POLICY ANALYSIS (3) dependence, and non-standard beliefs. (PR: ECO 6424) 4202 E. Fowler Avenue The application of economic theory to matters of public policy. (PR: ECO 3101) ECP 6205 LABOR ECONOMICS I (3) Tampa, FL 33620 Labor demand and supply, unemployment, discrimination in labor ECO 6206 MACROECONOMICS I (3) markets, labor force statistics. (PR: ECO 3101 or ECO 6115) Dynamic analysis of the determination of income, employment, prices, and interest rates. (PR: ECO 6405) ECP 7207 LABOR ECONOMICS II (3) Advanced study of labor economics including analysis of the wage Doctor of Philosophy ECO 7207 MACROECONOMICS II (3) structure, labor unions, labor mobility, and unemployment. (PR: Topics in advanced macroeconomic theory with a particular emphasis ECP 6205) on quantitative and empirical applications. -

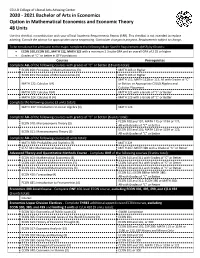

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

Logotipo EUSTAT

EUSKAL ESTATISTIKA ERAKUNDA INSTITUTO VASCO DE ESTADÍSTICA Mirodata from the Estatistic on Marriages 2010 Description of file EUSKAL ESTATISTIKA ERAKUNDA INSTITUTO VASCO DE ESTADÍSTICA Microdata from the Estatistic on Marriages 2010 Description of file CONTENTS 1. Introduction........................................ ¡Error! Marcador no definido. 2. Criteria for selection of variables ........ ¡Error! Marcador no definido. 2.1 Criteria of sensitivity......................¡Error! Marcador no definido. 2.2 Criteria of confidentiality ................¡Error! Marcador no definido. 3. Registry design ................................... ¡Error! Marcador no definido. 4. Description of variables ...................... ¡Error! Marcador no definido. APPENDIX 1............................................ ¡Error! Marcador no definido. Microdata files request sheet 1 EUSKAL ESTATISTIKA ERAKUNDA INSTITUTO VASCO DE ESTADÍSTICA Microdata from the Estatistic on Marriages 2010 Description of file 1. Introduction The statistical operation on Marriages provides information on marriages that affects residents in the Basque Country. The files for the Estatistic on Marriages constitute a product for circulation that targets users with experience in analyzing and processing microdata. This format provides an added value to the user, permitting him or her to carry out data exploitation and analysis that, for obvious limitations, cannot be covered by current circulation in the form of tables, publications and reports. The microdata file corresponding to Marriages is described in this report. The circulation of the Marriages file with data from the first spouse combined with information on the second spouse is carried out on the basis of the usefulness and quality of the information that is going to be included as well as the interest for the user, because it is more beneficial for the person receiving the data to be able to work with them in a combined form. -

International Undergraduate Prospectus 2011 E at Du a R UNDERG Contents

International Undergraduate Prospectus 2011 Prospectus Undergraduate International UNDERGRAduATE Contents UWS AND YOU ..................... 1 Why choose UWS? . 2 Student Services and Facilities . 4 Teaching and Learning – a different style . 6 UWS Life – Where will you study? UWS campuses . 7 Bankstown campus . 8 Campbelltown campus . 10 Hawkesbury campus . 12 Nirimba (Blacktown) campus . 14 Parramatta campus . 16 Penrith campus . 18 Westmead precinct . 20 UWS Life Accommodation . 22 Preparing for life at UWS . 24 Your study destination . 26 Cost of living . 28 Working in Australia . 30 COURSE GUIDE .................... 31 Course and Career Index . 32 Agriculture, Horticulture, Food and Natural Sciences and Animal Science . 34 Arts, International Studies, Languages, Interpreting and Translation . 38 Business . 41 Communication, Design and Media . 49 Computing and Information Technology . 51 Engineering, Construction and Industrial Design . 54 Forensics, Policing and Criminology . 60 Health and Sport Sciences . 62 Law . 68 Medicine . 71 Natural Environment and Tourism . 72 Nursing . 76 Psychology . 78 Sciences . 80 Social Sciences . 85 Teaching and Education . 87 ADMISSION ....................... 91 Academic entry requirements . 92 Undergraduate coursework entry requirements and 2011 fees . 94 English language entry requirements . 100 UWSCollege – your pathway to UWS . 101 How to apply . 106 Important information . 108 International student undergraduate application form . 109 UWS and You U UWS AND YO Jasper Duineveld, Netherlands » Bachelor of Arts (Psychology) ‘My experience at UWS has taught me that there are so many possibilities in life and every part has a positive outlook. The people and especially the lecturers at UWS are great, they are always willing to help you out.’ UWS has been recognised for outstanding contributions to student learning at the 2010 national Australian Learning and Teaching Council (ALTC) Awards. -

OECD Comparable and Other Selected Small Area Indicators

PROJECT FACT SHEET OECD comparable and other selected small area indicators Vision statement This project will develop a suite of indicators across a number of domains which can Project deliverables be used to assess and measure local community (SLA) socio-economic performance. * Review of the literature on social indicators These indicators will be accessible to urban researchers via the AURIN portal. * Benchmarked indicators comparable with OECD indicators for wellbeing at national level and the appropriate benchmarks to derive small Project overview area estimates Measures and benchmarks of local socio-economic performance are important * A final report containing a technical description of the modelling, a technical description of the tools for research and policy surrounding sustainable and effective communities. database including metadata and instructions The final set of indicators will be informed by the OECD Indicators project (Society on the service, user manual on how to use. at a Glance). The set of indicators will cover the same domains as Society at a Glance * Suite of social indicators available through the (general context; self sufficiency; equity; health; and social cohesion), and where AURIN portal possible will use similar indicators (see Figure 1). These indicators will be Fig.1 Conceptual model of OECD Comparable and Other Small Area Social Indicators for Australia project The AURIN Project is an initiative of the Australian Government being conducted as part of the Super Science Initiative and financed from the Education Investment Fund. The University of Melbourne is the Commonwealth-appointed Lead Agent of the AURIN Project PROJECT FACT SHEET OECD comparable and other selected small area indicators Project overview cont’d Team provided for Statistical Local Areas in Australia using the latest available data. -

Syllabus - ECON 137 – Urban & Regional Economics Summer 2006 (Session C)

Syllabus - ECON 137 – Urban & Regional Economics Summer 2006 (session C) Instructor: Guillermo Ordonez ([email protected]) Lecture hours: Monday and Wednesday 1:00 – 3:05pm, Room: Dodd 175 Office hours: Monday and Wednesday 3:30 – 4:30pm, Room: Bunche 2265 Webpage: http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/061/econ137-1/ UCLA campus “A city within a city” (UCLA undergraduate admission webpage) “A great city is not to be confounded with a populous one” Aristotle (Ancient Greek Philosopher, 384 BC-322 BC) “Los Angeles is 72 suburbs in search of a city” Dorothy Parker (American short- story writer and poet, 1893-1967) “What I like about cities is that everything is king size, the beauty and the ugliness.” Joseph Brodsky (Russian born American Poet and Writer. Nobel Prize for Literature in 1987. 1940- 1996) Course description In this class we will study the economics of cities and urban problems by understanding the effects of geographic location on the decisions of individuals and firms. The importance of location in everyday choices is easily assessed from our day-to- day lives (especially living in LA!), yet traditional microeconomic models are spaceless, (i.e we do not account for geographic factors). First we will try to answer general and interesting questions such as, Why do cities exist? How do firms decide where to locate? Why do people live in cities? What determines the growth and size of a city? Which policies can modify the shape of a city? Having discussed why we live in cities, we will analyze the economic problems that arise because we are living in cities. -

COURSE OUTLINE ECON317 Urban and Regional Economics Semester 1, 2021 Department of Economics, 5Th Floor, Otago Business School

COURSE OUTLINE ECON317 Urban and Regional Economics Semester 1, 2021 Department of Economics, 5th Floor, Otago Business School Lecturer: Paul Thorsnes Room: 531 OBS Phone: 479 8359 Email: [email protected] Lectures: Monday 2:00pm-3:00pm Wednesday 2:00pm-3:00pm Thursday 3:00pm - 4:00pm Rooms: TBA Course Objectives The last two hundred years have witnessed a remarkable shift in population from rural to urban areas in developed countries. In New Zealand, at least 85% of the population now live in towns and cities. The objective of this paper is to apply the methods of microeconomic analysis to gain an understanding of why this is and of the forces that shape land development and resource allocation in urbanised areas. A general objective is to improve your ability to apply microeconomic analysis. The more specific objective is to build a working understanding of the economics of urban areas: (1) economic explanations of why cities exist and where they develop and why they grow; (2) how and why urban land develops as it does; and (3) the roles of local governments in influencing the allocation of resources in urban areas. Prerequisites The prerequisite for the paper is ECON201 (Microeconomics) or ECON271 (Intermediate Microeconomic Theory). You should be acquainted with the concepts and models developed in your microeconomics papers: supply-demand, elasticities, indifference curves/isoquants, comparative statics, and so on. We’ll employ some simple algebra, but most of the analysis will be done with the aid of graphs. Readings Readings underpin the lectures, but the lectures are intended to complement, not completely substitute for, the assigned readings. -

Viveros Situados En Las Zonas Tampón Para Fuego Bacteriano

Viveros situados en las zonas tampón para fuego bacteriano (Erwinia amylovora ) en aquellas Comunidades Autónomas que, en parte o en su totalidad, solicitaron su salida del reconocimiento de Zona Protegida. Año: 2018 Comunidad Autónoma Zona/s tampón Nombre y dirección del vivero/s Nº de registro del vivero/s ARBOLES FRUTALES ORERO, S.L ANDALUCÍA Batán – Reverte – Las MonjasAvenida de Brenes, 5 ES-01-41/0275 41318 Villaverde del Río (Sevilla) Zona Tampón bajo Aragón SAT PLAVISE ES-02-50-0149 Caspe nº1 C/Calvari, 3 Alguaire (Lérida) ARAGÓN Zona Tampón bajo Aragón PROSEPLAN ES-02-50-0018 Caspe nº2 c/ Santander-Mediterráneo, Calatayud (Zaragoza) Viveros FITOCLIMA, S.L. CASTILLA LA MANCHA Albacete ES-07-02-0106 C/ Antonio Machado, 81, 1º D, 02004, Albacete (Albacete - Las Peñas) Viveros Integrales El Ejidillo S.L Castilla y León -1 (Aldeonsancho, Valdesimnonte, San Pedro de No autorizada la comercialización a Zona Protegida. Positivo en 2013 Erwinia amylovora en ES-08-40-0015 Gaillo-León) vivero Argimiro Sobaco Crespo Castilla y León- 2 (Castrocalbón-León)No autorizada la comercialización a Zona Protegida. Positivo en 2018 Erwinia amylovora en ES-08-24-0010 zona circundante y parcelas de producción del vivero CASTILLA Y LEÓN Vivero Barra ES-08-24-004 Ctra. Madrid-Coruña Km 302,8-24750 La Bañeza (León) Castilla y León-3 (La Bañeza y limítrofes-León) Viveros Lombó ES-08-24-0031 Crta N-VI, km 303,7 24750 La Bañeza (León) Castilla y León-4 (San Esteban de Gormaz y El Burgo de Osma- Deda Ebro, S.L ES-08-42-0083 Soria) C/ Estacio - Puigverd de Lleida (Lleida) SAT PLAVISE ES-09-25-0025 Calvari, 3; 25128 Alguaire Cat 1 -Alguaire (Lleida) Viveros Gabandé SL ES-09-25-0016 CATALUÑA Camí Moncada, 9, 25196 Lleida Certiplant, SL Cat 2- Bellvis-Palau d´Anglesola-El Poal-Linyola- Vilasana (Lleida) ES-09-25-0012 C/ Industria, 7. -

Regional and Enviromental Economic Studies Master's Program

REGIONAL AND ENVIROMENTAL ECONOMIC STUDIES MASTER’S PROGRAM Valid: For students starting their studies in the 2020/2021/1 semester General Informations: Person responsible for the major: Dr. Márton Péti, associate professor Place of the training: Budapest, Székesfehérvár Training schedule: full-time Language of the training: Hungarian, English Is it offered as dual training: no Specializations: There is no specialisation in the English-language program. Training and outcome requirements 1. Master’s degree title: Regional and Environmental Economic Studies 2. The level of qualification attainable in the Master’s programme, and the title of the certification − qualification level: master- (magister, abbreviation: MSc) − qualification in Hungarian: okleveles közgazdász regionális és környezeti gazdaságtan szakon − qualification in English: Economist in Regional and Environmental Economic Studies 3. Training area: economics 4. Degrees accepted for admittance into the Master’s programme 4.1. Accepted with the complete credit value: undergraduate degrees of the economic sciences field, and the Agricultural Environmental Management Engineering, Rural Development Engineer and degrees from the agricultural field of training and the Geographer and Environmental Studies undergraduate courses from the natural sciences field of training. 4.2. May also be considered with the completion of the credits defined in section 9.3: undergraduate and Master’s courses and courses as defined as per Act LXXX of 1993 on higher education that are accepted by the higher education institution’s credit transfer committee based on a comparison of the studies that serve as the basis of the credits. 5. Training duration, in semesters: 4 semesters 6. The number of credits to be completed for the Master’s degree: 120 credits − degree orientation: theory oriented (60-70 percent) − thesis credit value: 15 credits − minimum credit value of optional courses: 6 credits 7. -

The Basques by Julio Caro Baroja

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 5 The Basques by Julio Caro Baroja Translated by Kristin Addis Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 5 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2009 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Cover and series design © 2009 by Jose Luis Agote. Cover illustration: Fue painting by Julio Caro Baroja Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Caro Baroja, Julio. [Vascos. English] The Basques / by Julio Caro Baroja ; translated by Kristin Addis. p. cm. -- (Basque classics series ; no. 5) Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “The first English edition of the author’s 1949 classic on the Basque people, customs, and culture. Translation of the 1971 edition”-- Provided by publisher. *4#/ QCL ISBN 978-1-877802-92-8 (hardcover) 1. Basques--History. 2. Basques--Social life and customs. i. Title. ii. Series. GN549.B3C3713 2009 305.89’992--dc22 2009045828 Table of Contents Note on Basque Orthography.................................... vii Introduction to the First English Edition by William A. Douglass....................................... ix Preface .......................................................... 5 Introduction..................................................... 7 Part I 1. Types of Town Typical of the Basque Country: Structure of the Settlements of the Basque-Speaking Region and of the Central and Southern Areas of Araba and Navarre.......