Regional Economics: Understanding the Third Great Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor of Philosophy in Economics

ECO 6525 PUBLIC SECTOR ECONOMICS (3) Course Information Introduction to the public sector and the allocation of resources, emphasis on market failure and the economic role of government. ECO 6115 MICROECONOMICS I (3) (PR: ECO 6115) Microeconomic behavior of consumers, producers, and resource suppliers, price determination in output and factor markets, general ECO 6936 FORECASTING AND ECONOMIC TIME market equilibrium. (PR: ECO 3101, ECO 6405 or CI) SERIES (3) Study of time series econometrics estimation with applications to ECO 7116 MICROECONOMICS II (3) economic forecasting. (PR: ECO 6424) Topics in advanced microeconomic theory, including general equilibrium, welfare economics, intertemporal choice, uncertainty, ECO 6936 BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS (3) University of South Florida information, and game theory. (PR: ECO 6115) Survey of evidence on departures of economic agents from rationality. Topics include present-based preferences, reference College of Arts and Sciences ECO 6120 ECONOMIC POLICY ANALYSIS (3) dependence, and non-standard beliefs. (PR: ECO 6424) 4202 E. Fowler Avenue The application of economic theory to matters of public policy. (PR: ECO 3101) ECP 6205 LABOR ECONOMICS I (3) Tampa, FL 33620 Labor demand and supply, unemployment, discrimination in labor ECO 6206 MACROECONOMICS I (3) markets, labor force statistics. (PR: ECO 3101 or ECO 6115) Dynamic analysis of the determination of income, employment, prices, and interest rates. (PR: ECO 6405) ECP 7207 LABOR ECONOMICS II (3) Advanced study of labor economics including analysis of the wage Doctor of Philosophy ECO 7207 MACROECONOMICS II (3) structure, labor unions, labor mobility, and unemployment. (PR: Topics in advanced macroeconomic theory with a particular emphasis ECP 6205) on quantitative and empirical applications. -

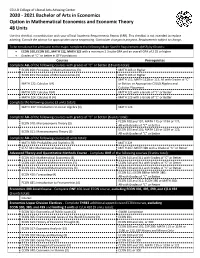

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

International Undergraduate Prospectus 2011 E at Du a R UNDERG Contents

International Undergraduate Prospectus 2011 Prospectus Undergraduate International UNDERGRAduATE Contents UWS AND YOU ..................... 1 Why choose UWS? . 2 Student Services and Facilities . 4 Teaching and Learning – a different style . 6 UWS Life – Where will you study? UWS campuses . 7 Bankstown campus . 8 Campbelltown campus . 10 Hawkesbury campus . 12 Nirimba (Blacktown) campus . 14 Parramatta campus . 16 Penrith campus . 18 Westmead precinct . 20 UWS Life Accommodation . 22 Preparing for life at UWS . 24 Your study destination . 26 Cost of living . 28 Working in Australia . 30 COURSE GUIDE .................... 31 Course and Career Index . 32 Agriculture, Horticulture, Food and Natural Sciences and Animal Science . 34 Arts, International Studies, Languages, Interpreting and Translation . 38 Business . 41 Communication, Design and Media . 49 Computing and Information Technology . 51 Engineering, Construction and Industrial Design . 54 Forensics, Policing and Criminology . 60 Health and Sport Sciences . 62 Law . 68 Medicine . 71 Natural Environment and Tourism . 72 Nursing . 76 Psychology . 78 Sciences . 80 Social Sciences . 85 Teaching and Education . 87 ADMISSION ....................... 91 Academic entry requirements . 92 Undergraduate coursework entry requirements and 2011 fees . 94 English language entry requirements . 100 UWSCollege – your pathway to UWS . 101 How to apply . 106 Important information . 108 International student undergraduate application form . 109 UWS and You U UWS AND YO Jasper Duineveld, Netherlands » Bachelor of Arts (Psychology) ‘My experience at UWS has taught me that there are so many possibilities in life and every part has a positive outlook. The people and especially the lecturers at UWS are great, they are always willing to help you out.’ UWS has been recognised for outstanding contributions to student learning at the 2010 national Australian Learning and Teaching Council (ALTC) Awards. -

OECD Comparable and Other Selected Small Area Indicators

PROJECT FACT SHEET OECD comparable and other selected small area indicators Vision statement This project will develop a suite of indicators across a number of domains which can Project deliverables be used to assess and measure local community (SLA) socio-economic performance. * Review of the literature on social indicators These indicators will be accessible to urban researchers via the AURIN portal. * Benchmarked indicators comparable with OECD indicators for wellbeing at national level and the appropriate benchmarks to derive small Project overview area estimates Measures and benchmarks of local socio-economic performance are important * A final report containing a technical description of the modelling, a technical description of the tools for research and policy surrounding sustainable and effective communities. database including metadata and instructions The final set of indicators will be informed by the OECD Indicators project (Society on the service, user manual on how to use. at a Glance). The set of indicators will cover the same domains as Society at a Glance * Suite of social indicators available through the (general context; self sufficiency; equity; health; and social cohesion), and where AURIN portal possible will use similar indicators (see Figure 1). These indicators will be Fig.1 Conceptual model of OECD Comparable and Other Small Area Social Indicators for Australia project The AURIN Project is an initiative of the Australian Government being conducted as part of the Super Science Initiative and financed from the Education Investment Fund. The University of Melbourne is the Commonwealth-appointed Lead Agent of the AURIN Project PROJECT FACT SHEET OECD comparable and other selected small area indicators Project overview cont’d Team provided for Statistical Local Areas in Australia using the latest available data. -

Syllabus - ECON 137 – Urban & Regional Economics Summer 2006 (Session C)

Syllabus - ECON 137 – Urban & Regional Economics Summer 2006 (session C) Instructor: Guillermo Ordonez ([email protected]) Lecture hours: Monday and Wednesday 1:00 – 3:05pm, Room: Dodd 175 Office hours: Monday and Wednesday 3:30 – 4:30pm, Room: Bunche 2265 Webpage: http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/061/econ137-1/ UCLA campus “A city within a city” (UCLA undergraduate admission webpage) “A great city is not to be confounded with a populous one” Aristotle (Ancient Greek Philosopher, 384 BC-322 BC) “Los Angeles is 72 suburbs in search of a city” Dorothy Parker (American short- story writer and poet, 1893-1967) “What I like about cities is that everything is king size, the beauty and the ugliness.” Joseph Brodsky (Russian born American Poet and Writer. Nobel Prize for Literature in 1987. 1940- 1996) Course description In this class we will study the economics of cities and urban problems by understanding the effects of geographic location on the decisions of individuals and firms. The importance of location in everyday choices is easily assessed from our day-to- day lives (especially living in LA!), yet traditional microeconomic models are spaceless, (i.e we do not account for geographic factors). First we will try to answer general and interesting questions such as, Why do cities exist? How do firms decide where to locate? Why do people live in cities? What determines the growth and size of a city? Which policies can modify the shape of a city? Having discussed why we live in cities, we will analyze the economic problems that arise because we are living in cities. -

COURSE OUTLINE ECON317 Urban and Regional Economics Semester 1, 2021 Department of Economics, 5Th Floor, Otago Business School

COURSE OUTLINE ECON317 Urban and Regional Economics Semester 1, 2021 Department of Economics, 5th Floor, Otago Business School Lecturer: Paul Thorsnes Room: 531 OBS Phone: 479 8359 Email: [email protected] Lectures: Monday 2:00pm-3:00pm Wednesday 2:00pm-3:00pm Thursday 3:00pm - 4:00pm Rooms: TBA Course Objectives The last two hundred years have witnessed a remarkable shift in population from rural to urban areas in developed countries. In New Zealand, at least 85% of the population now live in towns and cities. The objective of this paper is to apply the methods of microeconomic analysis to gain an understanding of why this is and of the forces that shape land development and resource allocation in urbanised areas. A general objective is to improve your ability to apply microeconomic analysis. The more specific objective is to build a working understanding of the economics of urban areas: (1) economic explanations of why cities exist and where they develop and why they grow; (2) how and why urban land develops as it does; and (3) the roles of local governments in influencing the allocation of resources in urban areas. Prerequisites The prerequisite for the paper is ECON201 (Microeconomics) or ECON271 (Intermediate Microeconomic Theory). You should be acquainted with the concepts and models developed in your microeconomics papers: supply-demand, elasticities, indifference curves/isoquants, comparative statics, and so on. We’ll employ some simple algebra, but most of the analysis will be done with the aid of graphs. Readings Readings underpin the lectures, but the lectures are intended to complement, not completely substitute for, the assigned readings. -

Regional and Enviromental Economic Studies Master's Program

REGIONAL AND ENVIROMENTAL ECONOMIC STUDIES MASTER’S PROGRAM Valid: For students starting their studies in the 2020/2021/1 semester General Informations: Person responsible for the major: Dr. Márton Péti, associate professor Place of the training: Budapest, Székesfehérvár Training schedule: full-time Language of the training: Hungarian, English Is it offered as dual training: no Specializations: There is no specialisation in the English-language program. Training and outcome requirements 1. Master’s degree title: Regional and Environmental Economic Studies 2. The level of qualification attainable in the Master’s programme, and the title of the certification − qualification level: master- (magister, abbreviation: MSc) − qualification in Hungarian: okleveles közgazdász regionális és környezeti gazdaságtan szakon − qualification in English: Economist in Regional and Environmental Economic Studies 3. Training area: economics 4. Degrees accepted for admittance into the Master’s programme 4.1. Accepted with the complete credit value: undergraduate degrees of the economic sciences field, and the Agricultural Environmental Management Engineering, Rural Development Engineer and degrees from the agricultural field of training and the Geographer and Environmental Studies undergraduate courses from the natural sciences field of training. 4.2. May also be considered with the completion of the credits defined in section 9.3: undergraduate and Master’s courses and courses as defined as per Act LXXX of 1993 on higher education that are accepted by the higher education institution’s credit transfer committee based on a comparison of the studies that serve as the basis of the credits. 5. Training duration, in semesters: 4 semesters 6. The number of credits to be completed for the Master’s degree: 120 credits − degree orientation: theory oriented (60-70 percent) − thesis credit value: 15 credits − minimum credit value of optional courses: 6 credits 7. -

Lessons for Regional Policy from the New Economic Geography and the Endogenous Growth Theory

Lessons for Regional Policy from the New Economic Geography and the Endogenous Growth Theory Helmut Karl; Ximena Fernanda Matus Velasco Lessons for Regional Policy from the New Economic Geography and the Endogenous Growth Theory Contents 1. Introduction 2. New Economic Geography Theory 3. Endogenous Growth Theory 4. New Economic Geography and Endogenous Growth Theories 5. Empirical Background and Discussion 6. Policy Implications 6.1 Objectives of Regional Policy 6.2 Policy Implications of the New Economic Geography Theory 6.3 Policy Implications of the Endogenous Growth Theory References 1. Introduction The configuration of the European Union has produced a deep transformation in all its Member States. Particularly, the geographic structure in all the area has changed with the disappearance of political and economic frontiers. Now, regions compete beyond their national borders, they compete for the European and international markets. Within this restructuring process, the spatial development in the European Union is characteri- sed by the division between dynamic centres with high economic activity and those with low economic activity. This structure of the territory has been identified at different levels: the core-periphery divide, the north-south divide and with the process of Euro- pean enlargement the east-west divide. The regional unbalances in economic growth and in the spatial distribution of eco- nomic activities have become an unquestionable reality. However, the causes which yield in some regions to more growth than others; as well as the forces leading to spatial agglomeration are still controversial. The role of the European institutions is another relevant topic of the discussion in the political and academic arena. -

Department of Economics Marketing Research, Or Public Administration

science, computer science, statistics, mathematics, finance, management, Department of Economics marketing research, or public administration. 2044 Constant Hall Admission (757) 683-3567 In addition to the University’s graduate admission requirements, applicants Christopher B. Colburn, Chair seeking regular admission must have at least a 3.0 grade point average in their major. Applicants are required to take either the Graduate Record Master of Arts—Economics Examination (GRE) or the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT), and they must submit at least one letter of recommendation. If undergraduate Timothy M. Komarek, Graduate Program Director GPA>3.3 the GRE or GMAT will be waived. If the undergraduate grade Economics is “the social science concerned with how individuals, point average falls below that required for regular status, applicants may institutions, and society make optimal choices under conditions of scarcity.” qualify for provisional admission. This is a broad field, covering everything from unemployment and inflation to stock market crashes and depressions, from perfect competition Requirements among firms to oligopoly and monopoly. Microeconomics studies firms, Undergraduate prerequisites include calculus (three credit hours), statistics consumers, goods markets, resource markets, labor markets, and the (three credit hours), an intermediate microeconomics, or intermediate price system. It gives recommendations about how to deal with pollution macroeconomics with grades of at least B. Students who do not yet meet and auctions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Macroeconomics studies the undergraduate prerequisites can complete those courses at Old Dominion unemployment, inflation, money supplies, interest rates, exchange rates, University before taking the advanced courses. national debt, and economic growth. Economics is concerned with Thirty semester credit hours (ten courses) of approved graduate work the problems of incentives, wealth, poverty, and income distribution. -

Regional Economic Development in Theory and Practice

10973-01_PT1-CH01_REV.qxd 2/6/08 3:41 PM Page 3 1 Regional Economic Development in Theory and Practice Richard M. McGahey lthough the American economy has entered the sixth year of the current Aexpansion, job growth during the current recovery is significantly slower than in the past. On a peak-to-peak basis, most indicators for the current recov- ery lag behind the postwar average—GDP growth is 2.6 percent, compared to a postwar average 3.3 percent gain; wages and salaries are 1.2 percent higher, com- pared to a postwar average of 2.8 percent; and employment is up only 0.6 percent, compared to a postwar average of 1.7 percent.1 And there is a marked slowdown since 2003. Between 2003 and the first half of 2007, real median hourly wages have actually declined by 1.1 percent, and even for the top 20 percent of wage earners, hourly wages have risen by only 0.5 percent. Incomes also are growing significantly slower than productivity during this recovery. Since 2000, overall productivity is up by 19.8 percent, while real weekly earnings rose by 3.5 percent for women and actually declined by one percentage point for men.2 So although the American economy continues to grow, it is producing jobs at a slower rate than in typical recoveries, and many of those jobs are actually paying declining real wages. Richard McGahey is a program officer at the Ford Foundation. The views expressed in this chap- ter are his. 3 10973-01_PT1-CH01_REV.qxd 2/6/08 3:41 PM Page 4 4 richard m. -

Georgia Tech, Georgia State University A0072 B0072

U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202-5335 APPLICATION FOR GRANTS UNDER THE National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships CFDA # 84.015A PR/Award # P015A180072 Gramts.gov Tracking#: GRANT12659313 OMB No. , Expiration Date: Closing Date: Jun 25, 2018 PR/Award # P015A180072 **Table of Contents** Form Page 1. Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 e3 2. Standard Budget Sheet (ED 524) e6 3. Assurances Non-Construction Programs (SF 424B) e8 4. Disclosure Of Lobbying Activities (SF-LLL) e10 5. ED GEPA427 Form e11 Attachment - 1 (GT_GSU_GEPA_Section427_FINAL_19June20181021842892) e12 6. Grants.gov Lobbying Form e16 7. Dept of Education Supplemental Information for SF-424 e17 8. ED Abstract Narrative Form e18 Attachment - 1 (ABSTRACT_FINAL_22June20181021842932) e19 9. Project Narrative Form e20 Attachment - 1 (Table_of_contents___Narrative_1_1021842955) e21 10. Other Narrative Form e96 Attachment - 1 (Appendix_1_faculty_list_combined__6_20_18_FINAL_1021842934) e97 Attachment - 2 (Appendix_2_Course_list___6_20_18__FINAL1021842935) e335 Attachment - 3 (Appendix_3_PMFs_AGSC_FINAL_19June20181021842936) e435 Attachment - 4 (Appendix_4_letters_of_endorsement__FINAL_1021842937) e438 Attachment - 5 (Appendix_5_GT_AbsolutePriority_1_2_Statement_FINAL1021842968) e456 Attachment - 6 (Appendix_6_GSU_AbsolutePriority_1_2_Statement_FINAL1021842939) e459 Attachment - 7 (Appendix_7_FY2018_ProfileForm_GeorgiaTech_FINAL_22June20181021842940) e462 11. Budget Narrative Form e463 Attachment - 1 (Combined_Budget1021842933) -

REGIONAL ECONOMICS Regional Economics

REGIONAL ECONOMICS Regional Economics MARION TEMPLE Senior Lecturer in Economics School ofReal Estate Management Oxford Brookes University M St. Martin's Press © Marion Temple 1994 All rights reserved. No repmduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be repn>duced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WI P 9HE. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal pmsecution and civil claims for damages. First published in Great Britain 1994 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndrnills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives thmughout the world A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-333-57365-5 ISBN 978-1-349-23364-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-23364-9 First published in the United States of America 1994 by Scholarly and Reference Division, ST. MARTIN'S PRESS, INC., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 ISBN 978-0-312-12225-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for Contents List of Tables and Figures ix Acknowledgements xii Introduction XV 1 The Region and Regional Economics 1 THE REGIONAL FRAMEWORK 1 Regional Economics 1 The Place of the Region 2 The European Context 3 THE REGION 4