Urban Science: Integrated Theory from the First Cities to Sustainable Metropolises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

URBAN INFORMATICS COLLOQUIUM a Series of Papers and Discussions Examining Various Contemporary Intersections Between Urban Theory and Social Informatics

URBAN INFORMATICS COLLOQUIUM A series of papers and discussions examining various contemporary intersections between urban theory and social informatics Hosted by The Centre for the Study of Cities & Regions, Department of Geography Durham University & The Social Informatics Research Unit (SIRU), Department of Sociology University of York Sponsored by the ESRC e-Society Research Programme Friday 15 December 2006 - Saturday 16 December 2006 12:00pm - 5:00pm, Collingwood College, Durham DRAFT @ 9 November 2006 Day 1 Friday 15 December 12:00 – 13:15 Registration/Lunch 13:15 – 13:30 Welcome and Introduction Roger Burrows & Joe Painter Turn On/Tune Out: Miniaturisation, Mobilities and the Urban 13:30 – 14:30 Soundscape David Beer Charting the Ludodrome: the Hyperreal Urban Experiences of Video 14:30 – 15:30 Gamers Rowland Atkinson & Paul Willis (University of Tasmania) 15:30 – 16:00 Tea/Coffee Sentient Cities: Ubiquitous Computing and the Politics of Urban 16:00 – 17:00 Space Mike Crang & Steve Graham New Spaces of (Dis)engagement? Social Politics, Urban 17:00 – 18:00 Technologies and the Rezoning of the City Nick Ellison 18:00 – 19:30 Bar 19:30 Dinner Day 2 Saturday 16 December Data Construction in Urban Informatics: Applying Nicholas 09:00 – 10:00 Bateson’s Theory of Data Construction to Urban Simulation Emma Uprichard Public Cartographies of Knowing Capitalism and the Re-visualisation 10:00 – 11:00 of Places: A Challenged to empirical Society Michael Hardey & Roger Burrows 11:00 – 11:30 Tea/Coffee Homeless People, Mashups and Primary Keys: -

The Reassertion of Race, Space, and Punishment's Place in Urban

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2013, volume 31, pages 372 – 380 doi:10.1068/d311r1 Review essay: The reassertion of race, space, and punishment’s place in urban sociology and critical criminology† In Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect and The Collapse of American Criminal Justice Robert J Sampson and William Stuntz, respectively, highlight the intersection and reassertion—to draw upon and extend the work of Edward Soja (2011)—of race, space, and punishment’s place in urban sociology, critical criminology, and postmodern geography (Massey, 2012; Sampson, 2012; Ludwig et al, 2012; Sharkey, 2013). The structural circumstances of deprivation and criminalization facing African-Americans that they both highlight, and the related racialized perceptions of criminality that are counterparts, appear to be some of the salient features that recently led to the murder of a young black teenager, Trayvon Martin, in the US state of Florida. Florida is one of many US states with new Stand Your Ground laws which have proliferated across the country, along with a noticeable uptick in so-called ‘justified homicides’. In this instance the inequalities of race and space highlighted by these two authors tragically came together as a neighborhood watch patrolman shot and killed Trayvon and shaped the lack of an initial official response, until massive protests broke out across the US against the failure of authorities to charge the assailant with a crime (Sampson, 2012; Sampson and Raudenbush, 2004). This review essay presents these two landmark books, offering an appreciation and critique of their interrelated arguments and setting them in the context of a wider literature on the evolution of spatial, social class, and racial relations right up to our contemporary present. -

Urban Informatics

Center for Urban Science + Progress NYC'S LEADING GRADUATE PROGRAM IN URBAN INFORMATICS FULL-TIME MS • PART-TIME MS ADVANCED CERTIFICATE YOUR CITY. YOUR LAB. YOUR DATA REVOLUTION. OUR LABORATORY IS NEW YORK CITY. OUR MISSION IS HISTORIC. The Center for Urban Science and Progress With NYC as its laboratory and classroom, (CUSP) was created as a historic partnership New York University's CUSP uses advances with NYU, the City of New York, and other in data creation, storage, and analytics to academic and industrial partners to make investigate and answer such questions. These cities around the world more efficient, livable, activities are making NYU CUSP the world’s equitable, and resilient. By 2050, 66 percent leading authority in the emerging field of of the world’s population is projected to live urban informatics. in urban areas. How can rapidly growing cities CUSP’s impact-driven research and provide a high quality of life to citizens of educational programs examine complex every socioeconomic status? How will they urban issues and contribute practical effectively and efficiently deliver services, solutions for challenges facing New York address resource allocation, and increase City and growing cities worldwide. citizens’ access to green space? 1 • NYU TANDON SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING GRADUATE PROGRAMS AT NYU CUSP AN INTENSIVE ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE Graduate programs at NYU CUSP offer through internships and practicums that a unique, interdisciplinary, and cutting-edge enable students to be successful in a wide approach that links data science, statistics range of career trajectories. and analytics, and mathematics with complex Our rigorous programs are designed to urban systems, urban management, and prepare you for a rewarding and fulfilling policy. -

Ethnographic Understandings of Ethnically Diverse Neighbourhoods to Inform Urban Design Practice

Local Environment The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability ISSN: 1354-9839 (Print) 1469-6711 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cloe20 Ethnographic understandings of ethnically diverse neighbourhoods to inform urban design practice Clare Rishbeth, Farnaz Ganji & Goran Vodicka To cite this article: Clare Rishbeth, Farnaz Ganji & Goran Vodicka (2017): Ethnographic understandings of ethnically diverse neighbourhoods to inform urban design practice, Local Environment, DOI: 10.1080/13549839.2017.1385000 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1385000 © 2017 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 10 Oct 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 684 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cloe20 Download by: [University of Sheffield] Date: 31 October 2017, At: 04:13 LOCAL ENVIRONMENT, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1385000 Ethnographic understandings of ethnically diverse neighbourhoods to inform urban design practice Clare Rishbeth , Farnaz Ganji and Goran Vodicka Department of Landscape, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The aim of this paper is to inform urban design practice through deeper Received 19 August 2016 understanding and analysis of the social dynamics of public outdoor Accepted 8 September 2017 space in ethnically diverse neighbourhoods. We hypothesise that KEYWORDS findings from ethnographic research can provide a resource that Public open space; literature improves cultural literacy and supports social justice in professional review; ethnicity; diversity; practice. The primary method is a meta-synthesis literature review of 24 urban design; UK ethnographic research papers, all of which explore some dimensions of public open space use and values in UK urban contexts characterised by ethnic and racial diversity. -

Regional Economics: Understanding the Third Great Transition

REGIONAL ECONOMICS: UNDERSTANDING THE THIRD GREAT TRANSITION Paul Krugman September 2019 Memo to young economists: the transition from fiery upstart to old fuddy-duddy elder statesman sneaks up on you. One day, it seems, you’re trying to turn everything upside down; the next thing you know you’ve turned into one of those old guys whose response to any new idea is “It’s trivial, it’s wrong, and I said it in 1962.” Sure enough, in a couple of weeks I’m giving the luncheon keynote speech at a Boston Fed conference on America’s growing regional disparities, basically providing a break and maybe some inspiration in between presentations by real researchers. The brief talk doesn’t require a paper, and I am not someone who reads prepared speeches. But I thought I might take the occasion to write down a few thoughts on the subject. Basically, I want to make three points: 1. The regional divergence we’ve seen since around 1980 probably isn’t trivial or transient. Instead, it reflects a shift in the underlying logic of regional growth — the kind of shift that theories of economic geography predict will happen now and then, when the balance between forces of agglomeration and those of dispersion crosses a tipping point. 2. This isn’t the first time this kind of transition has happened. In fact, it’s the third such shift in the history of the U.S. economy, which went through earlier eras of both regional divergence and regional convergence. 3. There are pretty good although not ironclad arguments for “place-based” policies to limit regional divergence. -

Cultivating the Commons an Assessment of the Potential for Urban Agriculture on Oakland's Public Land

Portland State University PDXScholar Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies and Publications and Presentations Planning 12-2010 Cultivating the Commons An Assessment of the Potential for Urban Agriculture on Oakland’s Public Land Nathan McClintock Portland State University, [email protected] Jenny Cooper University of California - Berkeley Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac Part of the Social Policy Commons, Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details McClintock, N., and Cooper, J. (2010). Cultivating the Commons An Assessment of the Potential for Urban Agriculture on Oakland’s Public Land. Available at www.urbanfood.org. This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Cultivating the Commons An Assessment of the Potential for Urban Agriculture on Oakland’s Public Land by Nathan McClintock & Jenny Cooper Department of Geography University of California, Berkeley REVISED EDITION – December 2010 ! i Cultivating the Commons An Assessment of the Potential for Urban Agriculture on Oakland’s Public Land Nathan McClintock & Jenny Cooper Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley October 2009, revised December 2010 In collaboration with: City Slicker Farms HOPE Collaborative Institute for Food & Development Policy (Food First) This project was funded in part by the HOPE Collaborative. City Slicker Farms was the fiscal sponsor. -

What Can I Do with a Major In… URBAN STUDIES by 2025, 75 Percent of the World's Population Will Live in Cities

What can I do with a major in… URBAN STUDIES By 2025, 75 percent of the world's population will live in cities. The Urban Studies major prepares students to establish, develop, and carry out ministry or other work in an increasingly urban world, both in the local church and through parachurch ministries, local government and secular non-profits, as well as to lay a foundation for graduate study. Includes one year of course work and internship while living in Minneapolis’ inner city. What types of work are related to this degree? Who employs people with this degree? Inner-city missions Cross cultural ministries, domestic or foreign Refugee resettlement Federal, state and local governments Church staff member AmeriCorps programs Community organization director (cross cultural) Social and human services organizations Evangelism and church planting Para church organizations Government work Community development organizations Hospitality ministries Educational programs (non-licensure) Refugee resettlement Parks and recreation programs Program development Family services agencies/programs (financial, family planning, Job development health and wellness, marriage, vocational, food/housing Life skills coaching assistance, military family support) Residential counselor National and international humanitarian aid organizations Human services worker or case manager Advocacy (legal or adoption) More information online at ONETonline.org General Strategies for Success: An understanding of economics, sociology, anthropology and political science/public policy can enhance your employability and effectiveness. Urban studies majors have an understanding of issues facing society in urban areas. This understanding of other cultures and trends is valued by employers in many industries including education, government, and business. Learn at least one additional language and learn about ESL teaching strategies. -

Handbook Headings

School of Environment, Education and Development Planning and Environmental Management MSc Global Urban Development and Planning 2019-2020 Programme Handbook www.seed.manchester.ac.uk/studentintranet ii School of Environment, Education and Development Planning and Environmental Management MSc Global Urban Development and Planning 2019-2020 Programme Handbook www.seed.manchester.ac.uk/studentintranet iii iv Welcome to the School of Environment, Education and Development The School of Environment, Education and Development (SEED) was formed in August 2013 and forges an interdisciplinary partnership combining Geography and Planning and Environmental Management with the Global Development Institute (GDI), the Manchester School of Architecture and the Manchester Institute of Education, thus uniting research into social and environmental dimensions of human activity. Each department has its own character and the School seeks to retain this whilst building on our interdisciplinary strengths. The Global Development Institute (GDI) is a culmination of an impressive history of development studies at The University of Manchester which has spanned more than 60 years and unites the strengths of the Institute for Development and Policy Management (IDPM) and the Brooks World Poverty Institute. IDPM was established in 1958 and became the UK’s largest University-based International Development Studies centre, with over thirty Manchester-based academic and associated staff. Its objective is to promote social and economic development, particularly within lower-income countries and for disadvantaged groups, by enhancing the capabilities of individuals and organisations through education, training, consultancy, research and policy analysis. To build on this tradition, the University created in SEED the Brooks World Poverty Institute, a multidisciplinary centre of excellence researching poverty, poverty reduction, inequality and growth. -

Doctor of Philosophy in Economics

ECO 6525 PUBLIC SECTOR ECONOMICS (3) Course Information Introduction to the public sector and the allocation of resources, emphasis on market failure and the economic role of government. ECO 6115 MICROECONOMICS I (3) (PR: ECO 6115) Microeconomic behavior of consumers, producers, and resource suppliers, price determination in output and factor markets, general ECO 6936 FORECASTING AND ECONOMIC TIME market equilibrium. (PR: ECO 3101, ECO 6405 or CI) SERIES (3) Study of time series econometrics estimation with applications to ECO 7116 MICROECONOMICS II (3) economic forecasting. (PR: ECO 6424) Topics in advanced microeconomic theory, including general equilibrium, welfare economics, intertemporal choice, uncertainty, ECO 6936 BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS (3) University of South Florida information, and game theory. (PR: ECO 6115) Survey of evidence on departures of economic agents from rationality. Topics include present-based preferences, reference College of Arts and Sciences ECO 6120 ECONOMIC POLICY ANALYSIS (3) dependence, and non-standard beliefs. (PR: ECO 6424) 4202 E. Fowler Avenue The application of economic theory to matters of public policy. (PR: ECO 3101) ECP 6205 LABOR ECONOMICS I (3) Tampa, FL 33620 Labor demand and supply, unemployment, discrimination in labor ECO 6206 MACROECONOMICS I (3) markets, labor force statistics. (PR: ECO 3101 or ECO 6115) Dynamic analysis of the determination of income, employment, prices, and interest rates. (PR: ECO 6405) ECP 7207 LABOR ECONOMICS II (3) Advanced study of labor economics including analysis of the wage Doctor of Philosophy ECO 7207 MACROECONOMICS II (3) structure, labor unions, labor mobility, and unemployment. (PR: Topics in advanced macroeconomic theory with a particular emphasis ECP 6205) on quantitative and empirical applications. -

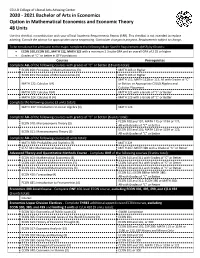

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

On the Material and Immaterial Architecture of Organised Positivism in Britain

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Wilson, M 2015 On the Material and Immaterial Architecture of Organised Positivism in Britain. Architectural Histories, 3(1): 15, pp. 1–21, DOI: http:// +LVWRULHV dx.doi.org/10.5334/ah.cr RESEARCH ARTICLE On the Material and Immaterial Architecture of Organised Positivism in Britain Matthew Wilson* Positivism captured the Victorian imagination. Curiously, however, no work has focused on the architec- tural history and theory of Positivist halls in Britain. Scholars present these spaces of organised Positiv- ism as being the same in thought and action throughout their existence, from the 1850s to the 1940s. Yet the British Positivists’ inherently different views of the work of their leader, the French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798–1857), caused such friction between them that a great schism in the movement occurred in 1878. By the 1890s two separate British Positivist groups were using different space and syntax types for manifesting a common goal: social reorganisation. The raison d’être of these institu- tions was to realize Comte’s utopian programme, called the Occidental Republic. In the rise of the first organised Positivist group in Britain, Richard Congreve’s Chapel Street Hall championed the religious ritu- alism and cultural festivals of Comte’s utopia; the terminus for this theory and practice was a temple typology, as seen in the case of Sydney Style’s Liverpool Church of Humanity. Following the Chapel Street Hall schism of 1878, Newton Hall was in operation by 1881 and under the direction of Frederic Harrison. Harrison’s group coveted intellectual and humanitarian activities over rigid ritualism; this tradition culmi- nated in a synthetic, multi-function hall typology, as seen in the case of Patrick Geddes’ Outlook Tower. -

URBAN STUDIES ACADEMIC MAP: DEGREE BS (120 CREDIT HOURS) Offered Evenings, Weekends, and Online

URBAN STUDIES ACADEMIC MAP: DEGREE BS (120 CREDIT HOURS) Offered Evenings, Weekends, and Online This deg r e e map is a semester-‐by-‐semester sample course schedule for students majoring in Urban Studies. The milestones listed to the right of each se m e ste r are designed to keep a st ude nt on track to graduate in four years. The s chedule serves as a general guideline to help st ude nt s build a full schedule each se m es t e r . Milestones ar e courses and specia l requirements ne cessary fo r timely pro gress t o c omplete a major. When one or more milestones are missed, students should consult with an academic advisor to determine if another degree path would be more suitable. The mission of the Urban Studies program is to recruit, retain, and educate a diverse student body in the knowledge, skills and values of professional public service. In order to accomplish this mission, we will strive to do the following: • Meet the professional development needs of students and those employed in the public, nonprofit, health and urban sectors by providing a quality program that builds skills in and knowledge of sociology, social work, urban affairs, public administration & leadership; • Provide students with responsive, timely, and business friendly support services to promote retention and successful program completion; • Conduct research and service activities supportive of these educational purposes; and • Serve the public, nonprofit, health and urban sectors as a source of consultation, applied research, and knowledge of social programs, public policy & public management issues to the community.