Incorrigible Colonist: Ginger in Australia, 1788–1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aperitivos ~ Check out Our Wine and Drinks Card~

Aperitivos ~ Check out our wine and drinks card~ Aperitif 5,00 Hugo - prosecco, elderflower, mint, lemon peel Agua de Valencia - orange juice, vodka, gin, prosecco Aperol Spritz - aperol, prosecco, orange juice, soda Viper Hard Seltzer - sparkling spring water with 4% alcohol and lime Gin & Tonics 9,00 Lemon - tanqueray ten gin, lemon, juniper Herbs & Spices - tanqueray london dry, juniper, clove, cardamom, orange Ginger Rosemary - gordon’s london dry, ginger, lemon, rosemary Cocktails 8,00 Mojito - rum, lime, sugar, mint, soda water Cuba Libre - rum, lime, cola 43 Sour - licor 43, lemon, aquafaba, sugar water Sangria 5,00 / 9,50 / 18,00 Sangria Tinto - red wine, various drinks, fruits Alcohol free 5,00 Pimento - ginger beer, ginger tonic, chili and spices Hugo 0.0 - elderflower, lemon peel, mint, sprite, ice Nojito - mint, lime, sugar, soda water, apple juice The Fortress of the Alhambra, Granada Menu ~ suggestions ~ “under the Mediterranean sun” Menu Alhambra 35,00 “Take your time to enjoy tastings in multiple courses” seasoned pita bread - lebanese flat bread - turkish bread hummus - aioli - muhammarah - olives - smoked almonds manchego membrillo- feta - iberico chorizo - iberico paletta dades with pork belly - fried eggplant shorbat aldas - falafel casero - albóndigas vegetariano croquetas iberico - calamares köfta - tajine pollo - gambas al ajillo couscous harissa deliciosos dulces Menu Moro 32,00 “tapas and mezze menu in multiple servings” First round seasoned pita bread with aioli and muhamarah Second round tasting of multiple -

Spices-Spiced Fruit Bunswithoutpics

More Info On Spices Used in Spiced Fruit Buns CLOVES • Cloves are aromatic, dried flower buds that looks like little wooden nails • it has a very pungent aroma and flavour • It is pressed into oranges when making mulled wine or studded into glazed gammon • believed to be a cure for toothache • should be avoided by people with gastric disorders. NUTMEG • nutmeg fruit is the only tropical fruit that is the source of two different spices: nutmeg and mace • nutmeg is the actual seed of the nutmeg tree, whereas mace is the covering of the seed • nutmeg has a slightly sweeter flavour than mace a more delicate flavour. • It is better to buy whole nutmeg and grate it as and when you need it instead of buying ground nutmeg. • Nutmeg is used in soups, e.g. butternut soup, sauces, potato dishes, vegetable dishes, in baked goods, with egg nog • Used extensively in Indian & Malayian cuisines GINGER • Available in many forms, i.e. fresh, dried, powdered (see image below), pickled ginger, etc. • Powdered ginger is used in many savoury and sweet dishes and for baking traditional favourites such as gingerbread, brandy snaps, ginger beer, ginger ale • Fresh root ginger looks like a knobbly stem. It should be peeled and finely chopped or sliced before use. • Pickled ginger is eaten with sushi. CINNAMON • comes from the inner bark of a tree belonging to the laurel family. • Whole cinnamon is used in fruit compôtes, mulled wines and curries. • Ground cinnamon is used in puddings and desserts such as milk tart, cinnamon buns, to flavour cereal, in hot drinks, etc. -

Article Description EAN/UPC ARTIC ZERO TOFFEE CRUNCH 16 OZ 00852244003947 HALO TOP ALL NAT SMORES 16 OZ 00858089003180 N

Article Description EAN/UPC ARTIC ZERO TOFFEE CRUNCH 16 OZ 00852244003947 HALO TOP ALL NAT SMORES 16 OZ 00858089003180 NESTLE ITZAKADOOZIE 3.5 OZ 00072554211669 UDIS GF BREAD WHOLE GRAIN 24 OZ 00698997809302 A ATHENS FILLO DOUGH SHEL 15 CT 00072196072505 A B & J STRW CHSCK IC CUPS 3.5 OZ 00076840253302 A F FRZN YGRT FRCH VNLL L/FAT 64 OZ 00075421061022 A F I C BLACK WALNUT 16 OZ 00075421000021 A F I C BROWNIES & CREAM 64 OZ 00075421001318 A F I C HOMEMADE VANILLA 16 OZ 00075421050019 A F I C HOMEMADE VANILLA 64 OZ 00075421051016 A F I C LEMON CUSTARD 16 OZ 00075421000045 A F I C NEAPOLITAN 16 OZ 00075421000038 A F I C VANILLA 16 OZ 00075421000014 A F I C VANILLA 64 OZ 00075421001011 A F I C VANILLA FAT FREE 64 OZ 00075421071014 A F I C VANILLA LOW FAT 64 OZ 00075421022016 A RHODES WHITE DINN ROLLS 96 OZ 00070022007356 A STF 5CHS LASAGNA DBL SRV 18.25 OZ 00013800447197 ABSOLUTELY GF VEG CRST MOZZ CH 6 OZ 00073490180156 AC LAROCCO GRK SSM PZ 12.5 OZ 00714390001201 AF SAVORY TKY BRKFST SSG 7 OZ 00025317694001 AGNGRN BAGUETE ORIGINAL GF 15 OZ 00892453001037 AGNST THE GRAIN THREE CHEESE PIZZA 24 OZ 00892453001082 AGNST THE GRN PESTO PIZZA GLTN FREE 24OZ 00892453001105 AJINOMOTO FRIED RICE CHICKEN 54 OZ 00071757056732 ALDENS IC FRENCH VANILLA 48 OZ 00072609037893 ALDENS IC LT VANILLA 48 OZ 00072609033130 ALDENS IC SALTED CARAMEL 48 OZ 00072609038326 ALEXIA ARBYS SEASND CRLY FRIES 22 OZ 00043301370007 ALEXIA BTRNT SQSH BRN SUG SS 12OZ 00034183000052 ALEXIA BTRNT SQSH RISO PARM SS 12OZ 00034183000014 ALEXIA CLFLWR BTR SEA SALT 12 OZ 00034183000045 -

'A Ffitt Place for Any Gentleman'?

‘A ffitt place for any Gentleman’? GARDENS, GARDENERS AND GARDENING IN ENGLAND AND WALES, c. 1560-1660 by JILL FRANCIS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham July 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to investigate gardens, gardeners and gardening practices in early modern England, from the mid-sixteenth century when the first horticultural manuals appeared in the English language dedicated solely to the ‘Arte’ of gardening, spanning the following century to its establishment as a subject worthy of scientific and intellectual debate by the Royal Society and a leisure pursuit worthy of the genteel. The inherently ephemeral nature of the activity of gardening has resulted thus far in this important aspect of cultural life being often overlooked by historians, but detailed examination of the early gardening manuals together with evidence gleaned from contemporary gentry manuscript collections, maps, plans and drawings has provided rare insight into both the practicalities of gardening during this period as well as into the aspirations of the early modern gardener. -

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel On behalf of all the staff we would like to congratulate you on your upcoming wedding. Set in the former RAF camp, in the village of Boddam, the building has been totally transformed throughout into a contemporary stylish hotel featuring décor and furnishings. The Ballroom has direct access to the landscaped garden which overlooks Stirling Hill, making Buchan Braes Hotel the ideal venue for a romantic wedding. Our Wedding Team is at your disposal to offer advice on every aspect of your day. A wedding is unique and a special occasion for everyone involved. We take pride in individually tailoring all your wedding arrangements to fulfill your dreams. From the ceremony to the wedding reception, our professional staff take great pride and satisfaction in helping you make your wedding day very special. Buchan Braes has 44 Executive Bedrooms and 3 Suites. Each hotel room has been decorated with luxury and comfort in mind and includes all the modern facilities and luxury expected of a 4 star hotel. Your guests can be accommodated at specially reduced rates, should they wish to stay overnight. Our Wedding Team will be delighted to discuss the preferential rates applicable to your wedding in more detail. In order to appreciate what Buchan Braes Hotel has to offer, we would like to invite you to visit the hotel and experience firsthand the four star facilities. We would be delighted to make an appointment at a time suitable to yourself to show you around and discuss your requirements in more detail. -

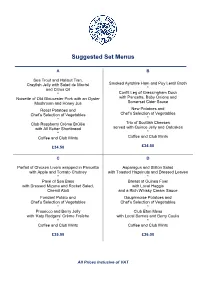

Scottish Menus

Suggested Set Menus A B Sea Trout and Halibut Tian, Crayfish Jelly with Salad de Maché Smoked Ayrshire Ham and Puy Lentil Broth and Citrus Oil * * Confit Leg of Gressingham Duck Noisette of Old Gloucester Pork with an Oyster with Pancetta, Baby Onions and Somerset Cider Sauce Mushroom and Honey Jus Roast Potatoes and New Potatoes and Chef’s Selection of Vegetables Chef’s Selection of Vegetables * * Club Raspberry Crème Brûlée Trio of Scottish Cheeses with All Butter Shortbread served with Quince Jelly and Oatcakes * * Coffee and Club Mints Coffee and Club Mints £34.50 £34.50 C D Parfait of Chicken Livers wrapped in Pancetta Asparagus and Stilton Salad with Apple and Tomato Chutney with Toasted Hazelnuts and Dressed Leaves * * Pavé of Sea Bass Breast of Guinea Fowl with Dressed Mizuna and Rocket Salad, with Local Haggis Chervil Aïoli and a Rich Whisky Cream Sauce Fondant Potato and Dauphinoise Potatoes and Chef’s Selection of Vegetables Chef’s Selection of Vegetables * * Prosecco and Berry Jelly Club Eton Mess with ‘Katy Rodgers’ Crème Fraîche with Local Berries and Berry Coulis * * Coffee and Club Mints Coffee and Club Mints £35.00 £36.00 All Prices Inclusive of VAT Suggested Set Menus E F Confit of Duck, Guinea Fowl and Apricot Rosettes of Loch Fyne Salmon, Terrine, Pea Shoot and Frissée Salad Lilliput Capers, Lemon and Olive Dressing * * Escalope of Seared Veal, Portobello Mushroom Tournedos of Border Beef Fillet, and Sherry Cream with Garden Herbs Fricasée of Woodland Mushrooms and Arran Mustard Château Potatoes and Chef’s Selection -

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources © Ryan, Lyndall; Pascoe, William; Debenham, Jennifer; Gilbert, Stephanie; Richards, Jonathan; Smith, Robyn; Owen, Chris; Anders, Robert J; Brown, Mark; Price, Daniel; Newley, Jack; Usher, Kaine, 2019. The information and data on this site may only be re-used in accordance with the Terms Of Use. This research was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council, PROJECT ID: DP140100399. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1340762 Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources 0 Abbreviations 1 Unpublished Archival Sources 2 Battye Library, Perth, Western Australia 2 State Records of NSW (SRNSW) 2 Mitchell Library - State Library of New South Wales (MLSLNSW) 3 National Library of Australia (NLA) 3 Northern Territory Archives Service (NTAS) 4 Oxley Memorial Library, State Library Of Queensland 4 National Archives, London (PRO) 4 Queensland State Archives (QSA) 4 State Libary Of Victoria (SLV) - La Trobe Library, Melbourne 5 State Records Of Western Australia (SROWA) 5 Tasmanian Archives And Heritage Office (TAHO), Hobart 7 Colonial Secretary’s Office (CSO) 1/321, 16 June, 1829; 1/316, 24 August, 1831. 7 Victorian Public Records Series (VPRS), Melbourne 7 Manuscripts, Theses and Typescripts 8 Newspapers 9 Films and Artworks 12 Printed and Electronic Sources 13 Colonial Frontier Massacres In Australia, 1788-1930: Sources 1 Abbreviations AJCP Australian Joint Copying Project ANU Australian National University AOT Archives of Office of Tasmania -

(AWU) and the Labour Movement in Queensland from 1913-1957

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year A history of the relationship between the Queensland branch of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) and the labour movement in Queensland from 1913-1957 Craig Clothier University of Wollongong Clothier, Craig, A history of the relationship between the Queensland branch of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) and the labour movement in Queensland from 1913-1957, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1996 This paper is posted at Research Online. Introduction Between 1913-1957 the Queensland Branch of the Australian Workers' Union (AWU) was the largest branch of the largest trade union in Australia. Throughout this period in Queensland the AWU accounted for approximately one third of all trade unionists in that state and at its peak claimed a membership in excess of 60 000. Consequenfly the AWU in Queensland was able to exert enormous influence over the labour movement in that state not only in industrial relations but also within the political sphere through its affiliation to the Australian Labor Party. From 1915-1957 the Labor Party in Queensland held office for all but the three years between 1929-1932. AWU officials and members dominated the Labor Cabinets of the period and of the eight Labor premiers five were members of the AWU, with two others closely aligned to the Union. Only the last Labor premier of the period, Vincent Clare Gair, owed no allegiance to the AWU. The AWU also used its numerical strength and political influence to dominate the other major decision-making bodies of Queensland's labour movement, most notably the Queensland Central Executive (QCE), that body's 'inner' Executive and the triennial Labor-in-Politics Convention. -

Christmas Past Recipes

Christmas Past Recipes Roasting the Christmas baron of beef at Windsor Castle in 1856. HISTORIC FOOD COOKERY COURSES Recipes of dishes made or sampled on The Taste of Christmas Cookery Courses 2009. TO MAKE A HACKIN. From a Gentleman in Cumberland. SIR, THERE are some Counties in England, whose Customs are never to be set aside and our Friends in Cumberland, as well as some of our Neighbours in Lancashire, and else-where, keep them up. It is a Custom with us every Christmas-Day in the Morning, to have, what we call an Hackin, for the Breakfast of the young Men who work about our House; and if this Dish is not dressed by that time it is Day-light, the Maid is led through the Town, between two Men, as fast as they can run with her, up Hill and down Hill, which she accounts a great shame. But as for the Receipt to make this Hackin, which is admired so much by us, it is as follows. Take the Bag or Paunch of a Calf, and wash it, and clean it well with Water and Salt ; then take some Beef-Suet, and shred it small, and shred some Apples, after they are pared and cored, very small. Then put in some Sugar, and some Spice beaten small, a little Lemon-Peel cut very fine, and a little Salt, and a good quantity of Grots, or whole Oat-meal, steep'd a Night in Milk; then mix thefe all together, and add as many Currans pick'd clean from the Stalks, and rubb'd in a coarfe Cloth ; but let them not be wash'd. -

Nyungar Tradition

Nyungar Tradition : glimpses of Aborigines of south-western Australia 1829-1914 by Lois Tilbrook Background notice about the digital version of this publication: Nyungar Tradition was published in 1983 and is no longer in print. In response to many requests, the AIATSIS Library has received permission to digitise and make it available on our website. This book is an invaluable source for the family and social history of the Nyungar people of south western Australia. In recognition of the book's importance, the Library has indexed this book comprehensively in its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Biographical Index (ABI). Nyungar Tradition by Lois Tilbrook is based on the South West Aboriginal Studies project (SWAS) - in which photographs have been assembled, not only from mission and government sources but also, importantly in Part ll, from the families. Though some of these are studio shots, many are amateur snapshots. The main purpose of the project was to link the photographs to the genealogical trees of several families in the area, including but not limited to Hansen, Adams, Garlett, Bennell and McGuire, enhancing their value as visual documents. The AIATSIS Library acknowledges there are varying opinions on the information in this book. An alternative higher resolution electronic version of this book (PDF, 45.5Mb) is available from the following link. Please note the very large file size. http://www1.aiatsis.gov.au/exhibitions/e_access/book/m0022954/m0022954_a.pdf Consult the following resources for more information: Search the Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Biographical Index (ABI) : ABI contains an extensive index of persons mentioned in Nyungar tradition. -

DINNER 20 20 Snacks Seafood Starters Salads & Sandwiches

Snacks Scotch Egg £5 DINNER 20 Yorkshire Buck £7 Fried Yorkshire Fettle & Talbot Honey £8 A Selection of Cured Pork from Todmorden £9 Mutton Scrumpets & Herb Mayonnaise £6.50 Sausage Roll £3 20 Starters Blue Bird Bakery Basket & Olives £5 Twice Baked Yorkshire Vintage Cheddar Soufflé, Spinach & Grain Mustard £7.50 Chopped Raw Hanger Steak with Tomato Dressing, Capers, Parsley, Croûtons & Horseradish £9.50 Roasted Beetroot & Hazelnut Salad, Crumbled Goats Cheese, Pear Puree £8 Pork Terrine, Mustard Fruits, Toast £8 Celeriac & Apple Soup with Toasted Hazelnuts (v) £6 Devilled Kidneys on Sourdough £7.50 Seafood Steamed Mussels with Leeks, Cider & Creme Fraiche £8.50 Freshly Picked Crab with Mayonnaise on Toast with Fennel & Dill Salad £12.50 Gin Cured Salmon with Chicory & Orange Salad £8.50 Smoked Haddock & Corn Chowder with Bacon £9.50 Salads & Sandwiches Autumn Salad - Black Fig, Beetroot, Spinach with Chickpeas, Goats Curd & Balsamic (vg) £11 Roast Pumpkin, Watercress, Lentils, Almonds & Pomegranate with Pumpkin Seed Dressing £11 Hot Smoked Salmon Bowl- Fine Beans, Radishes, Pickled Cucumber, Fennel, Dill & Horseradish £13 Spinach & Feta Filo Tart, Spiced Tomato Sauce, Green Beans £12.50 Butternut & Polenta Gnocchi with Wild Mushrooms, Onions, Mascarpone, ‘Ewe Beauty’ & Sage (v) £12.50 Sides Wensleydale Potatoes £4 | Hand Cut Chips £3 | French Fries £3 Minted New Potatoes £3 | Brussel Sprouts and Bacon £4 | Braised Red Cabbage £4 Spinach Buttered £4 | Wilted Autumn Greens £4 Mains Game Pie, Mashed Potatoes & Greens £17.50 Poached Hake -

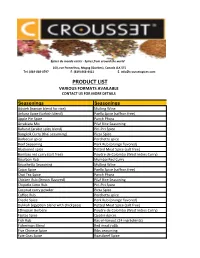

Product List Various Formats Available Contact Us for More Details

Épices du monde entier - Spices from around the world 160, rue Pomerleau, Magog (Quebec), Canada J1X 5T5 Tel. (819-868-0797 F. (819) 868-4411 E. [email protected] PRODUCT LIST VARIOUS FORMATS AVAILABLE CONTACT US FOR MORE DETAILS Seasonings Seasonings Advieh (iranian blend for rice) Mulling Wine Ankara Spice (turkish blend) Paella Spice (saffron free) Apple Pie Spice Panch Phora Arrabiata Mix Pilaf Rice Seasoning Baharat (arabic spicy blend) Piri-Piri Spice Bangkok Curry (thai seasoning) Pizza Spice Barbecue spice Porchetta spice Beef Seasoning Pork Rub (orange flavored) Blackened spice Potted Meat Spice (salt free) Bombay red curry (salt free) Poudre de Colombo (West Indies Curry) Bourbon Rub Mumbai Red Curry Bruschetta Seasoning Mulling Wine Cajun Spice Paella Spice (saffron free) Chai Tea Spice Panch Phora Chicken Rub (lemon flavored) Pilaf Rice Seasoning Chipotle-Lime Rub Piri-Piri Spice Coconut curry powder Pizza Spice Coffee Rub Porchetta spice Creole Spice Pork Rub (orange flavored) Dukkah (egyptian blend with chickpeas) Potted Meat Spice (salt free) Ethiopian Berbéré Poudre de Colombo (West Indies Curry) Fajitas Spice Quatre épices Fish Rub Ras-el-hanout (24 ingrédients) Fisherman Blend Red meat ru8b Five Chinese Spice Ribs seasoning Foie Gras Spice Roastbeef Spice Game Herb Salad Seasoning Game Spice Salmon Spice Garam masala Sap House Blend Garam masala balti Satay Spice Garam masala classic (whole spices) Scallop spice (pernod flavor) Garlic pepper Seafood seasoning Gingerbread Spice Seven Japanese Spice Greek Spice Seven