An Evaluation of Dalit Women in Bama's Sangati and P. Sivakami's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intersectionality and Feminist Politics Yuval-Davis, Nira

www.ssoar.info Intersectionality and Feminist Politics Yuval-Davis, Nira Postprint / Postprint Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: www.peerproject.eu Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Yuval-Davis, N. (2006). Intersectionality and Feminist Politics. European Journal of Women's Studies, 13(3), 193-209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506806065752 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter dem "PEER Licence Agreement zur This document is made available under the "PEER Licence Verfügung" gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zum PEER-Projekt finden Agreement ". For more Information regarding the PEER-project Sie hier: http://www.peerproject.eu Gewährt wird ein nicht see: http://www.peerproject.eu This document is solely intended exklusives, nicht übertragbares, persönliches und beschränktes for your personal, non-commercial use.All of the copies of Recht auf Nutzung dieses Dokuments. Dieses Dokument this documents must retain all copyright information and other ist ausschließlich für den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen information regarding legal protection. You are not allowed to alter Gebrauch bestimmt. Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments this document in any way, to copy it for public or commercial müssen alle Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise purposes, to exhibit the document in public, to perform, distribute auf gesetzlichen Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses or otherwise use the document in public. Dokument nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated Sie dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke conditions of use. vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Reassessing Religion and Politics in the Life of Jagjivan Ram¯

religions Article Reassessing Religion and Politics in the Life of Jagjivan Ram¯ Peter Friedlander South and South East Asian Studies Program, School of Culture History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2600, Australia; [email protected] Received: 13 March 2020; Accepted: 23 April 2020; Published: 1 May 2020 Abstract: Jagjivan Ram (1908–1986) was, for more than four decades, the leading figure from India’s Dalit communities in the Indian National Congress party. In this paper, I argue that the relationship between religion and politics in Jagjivan Ram’s career needs to be reassessed. This is because the common perception of him as a secular politician has overlooked the role that his religious beliefs played in forming his political views. Instead, I argue that his faith in a Dalit Hindu poet-saint called Ravidas¯ was fundamental to his political career. Acknowledging the role that religion played in Jagjivan Ram’s life also allows us to situate discussions of his life in the context of contemporary debates about religion and politics. Jeffrey Haynes has suggested that these often now focus on whether religion is a cause of conflict or a path to the peaceful resolution of conflict. In this paper, I examine Jagjivan Ram’s political life and his belief in the Ravidas¯ ¯ı religious tradition. Through this, I argue that Jagjivan Ram’s career shows how political and religious beliefs led to him favoring a non-confrontational approach to conflict resolution in order to promote Dalit rights. Keywords: religion; politics; India; Congress Party; Jagjivan Ram; Ravidas;¯ Ambedkar; Dalit studies; untouchable; temple building 1. -

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

THE DEVADASI SYSTEM: Temple Prostitution in India

UCLA UCLA Women's Law Journal Title THE DEVADASI SYSTEM: Temple Prostitution in India Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/37z853br Journal UCLA Women's Law Journal, 22(1) Author Shingal, Ankur Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.5070/L3221026367 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE DEVADASI SYSTEM: Temple Prostitution in India Ankur Shingal* Introduction Sexual exploitation, especially of children, is an internation- al epidemic.1 While it is difficult, given how underreported such crimes are, to arrive at accurate statistics regarding the problem, “it is estimated that approximately one million children (mainly girls) enter the multi-billion dollar commercial sex trade every year.”2 Although child exploitation continues to persist, and in many in- stances thrive, the international community has, in recent decades, become increasingly aware of and reactive to the issue.3 Thanks in large part to that increased focus, the root causes of sexual exploita- tion, especially of children, have become better understood.4 While the issue is certainly an international one, spanning nearly every country on the globe5 and is one that transcends “cul- tures, geography, and time,” sexual exploitation of minors is perhaps * J.D., Class of 2014, University of Chicago Law School; B.A. in Political Science with minor in South Asian Studies, Class of 2011, University of Califor- nia, Los Angeles. Currently an Associate at Quinn Emanuel Urquhart and Sul- livan, LLP. I would like to thank Misoo Moon, J.D. 2014, University of Chicago Law School, for her editing and support. 1 Press Release, UNICEF, UNICEF calls for eradication of commercial sexual exploitation of children (Dec. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

9789004400139 Webready Con

Vedic Cosmology and Ethics Gonda Indological Studies Published Under the Auspices of the J. Gonda Foundation Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Edited by Peter C. Bisschop (Leiden) Editorial Board Hans T. Bakker (Groningen) Dominic D.S. Goodall (Paris/Pondicherry) Hans Harder (Heidelberg) Stephanie Jamison (Los Angeles) Ellen M. Raven (Leiden) Jonathan A. Silk (Leiden) volume 19 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/gis Vedic Cosmology and Ethics Selected Studies By Henk Bodewitz Edited by Dory Heilijgers Jan Houben Karel van Kooij LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bodewitz, H. W., author. | Heilijgers-Seelen, Dorothea Maria, 1949- editor. Title: Vedic cosmology and ethics : selected studies / by Henk Bodewitz ; edited by Dory Heilijgers, Jan Houben, Karel van Kooij. Description: Boston : Brill, 2019. | Series: Gonda indological studies, ISSN 1382-3442 ; 19 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019013194 (print) | LCCN 2019021868 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004400139 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004398641 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Hindu cosmology. | Hinduism–Doctrines. | Hindu ethics. Classification: LCC B132.C67 (ebook) | LCC B132.C67 B63 2019 (print) | DDC 294.5/2–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019013194 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill‑typeface. ISSN 1382-3442 ISBN 978-90-04-39864-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-40013-9 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by Henk Bodewitz. -

Escaping the Master's House: Claudia Jones & the Black Marxist Feminist

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2017 Escaping the Master’s House: Claudia Jones & The Black Marxist Feminist Tradition Camryn S. Clarke Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Feminist Philosophy Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Camryn S., "Escaping the Master’s House: Claudia Jones & The Black Marxist Feminist Tradition". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2017. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/608 Escaping the Master’s House: Claudia Jones & The Black Marxist Feminist Tradition Camryn S. Clarke Page !1 of !45 Table of Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Introduction 5 To Be Black: Claudia Jones, Marcus Garvey, and Race 14 To Be Woman: Claudia Jones, Monique Wittig, and Sex 21 To Be A Worker: Claudia Jones, Karl Marx, and Class 27 To Be All Three: Claudia Jones and the Black Marxist Feminist Tradition 36 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 Page !2 of !45 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I cannot express enough thanks to my advisors for their support, encouragement, and enlightenment: Dr. Donna-Dale Marcano and Dr. Seth Markle. Thank you for always believing in me in times when I did not believe in myself. Thank you for exposing me to Human Rights and Philosophy through the lenses of gender, race, and class globally. Thank you. My completion of this project could not have been accomplished without the support and strength of the Black Women in my life: my great-grandmother Iris, my grandmother Hyacinth, my mother Angela, my sister Caleigh, and my aunt Audrey. -

13 White Woman Listen! Black Feminism and the Boundaries of Sisterhood

13 White Woman Listen! Black Feminism and the Boundaries of Sisterhood Hazel V. Carby I'm leaving evidence. And you got to leave evidence too. And your children got to leave evidence.... They burned all the documents.... We got to burn out what they put in our minds, like you burn out a wound. Except we got to keep what we need to bear witness. That scar that's left to bear witness. We got to keep it as visible as our blood. (Jones 1975) The black women's critique of history has not only involved us in coming to terms with "absences"; we have also been outraged by the ways in which it has made us visible, when it has chosen to see us. History has constructed our sexuality and our femininity as deviating from those qualities with which white women, as the prize objects of the Western world, have been endowed. We have also been defined in less than human terms (Jordon 1969). Our continuing struggle with History began with its "discovery" of us. However, this chapter will be concerned with herstory rather than history. We wish to address questions to the feminist theories that have been developed during the last decade; a decade in which black women have been fighting, in the streets, in the schools, through the courts, inside and outside the wage relation. The significance of these struggles ought to inform the writing of the herstory of women in Britain. It is fundamental to the development of a feminist theory and practice that is meaningful for black women. -

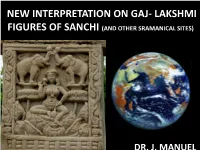

Female Deity of Sanchi on Lotus As Early Images of Bhu Devi J

NEW INTERPRETATION ON GAJ- LAKSHMI FIGURES OF SANCHI (AND OTHER SRAMANICAL SITES) nn DR. J. MANUEL THE BACK GROUND • INDRA RULED THE ROOST IN THE RGVEDIC AGE • OTHER GODS LIKE AGNI, SOMA, VARUN, SURYA BESIDES ASHVINIKUMARS, MARUTS WERE ALSO SPOKEN VERY HIGH IN THE LITERATURE • VISHNU IS ALSO KNOWN WITH INCREASING PROMINENCE SO MUCH SO IN THE LATE MANDALA 1 SUKT 22 A STRETCH OF SIX VERSES MENTION HIS POWER AND EFFECT • EVIDENTLY HIS GLORY WAS BEING FELT MORE AND MORE AS TIME PASSED • Mandal I Sukt 22 Richa 19 • Vishnu ki kripa say …….. Vishnu kay karyon ko dekho. Vay Indra kay upyukt sakha hai EVIDENTLY HIS GLORY WAS BEING FELT MORE AND MORE AS TIME PASSED AND HERO-GODS LIKE BALARAM AND VASUDEVA WERE ACCEPTED AS HIS INCARNATIONS • CHILAS IN PAKISTAN • AGATHOCLEUS COINS • TIKLA NEAR GWALIOR • ARE SOME EVIDENCE OF HERO-GODS BUT NOT VEDIC VISHNU IN SECOND CENTURY BC • There is the Kheri-Gujjar Figure also of the Therio anthropomorphic copper image BUT • FOR A LONG TIME INDRA CONTINUED TO HOLD THE FORT OF DOMINANCE • THIS IS SEEN IN EARLY SACRED LITERATURE AND ART ANTHROPOMORPHIC FIGURES • OF THE COPPER HOARD CULTURES ARE SAID TO BE INDRA FIGURES OF ABOUT 4000 YEARS OLD • THERE ARE MANY TENS OF FIGURES IN SRAMANICAL SITE OF INDRA INCLUDING AT SANCHI (MORE THAN 6) DATABLE TO 1ST CENTURY BCE • BUT NOT A SINGLE ONE OF VISHNU INDRA 5TH CENT. CE, SARNATH PARADOXICALLY • THERE ARE 100S OF REFERENCES OF VISHNU IN THE VEDAS AND EVEN MORE SO IN THE PURANIC PERIOD • WHILE THE REFERENCE OF LAKSHMI IS VERY FEW AND FAR IN BETWEEN • CURIOUSLY THE ART OF THE SUPPOSED LAXMI FIGURES ARE MANY TIMES MORE IN EARLY HISTORIC CONTEXT EVEN IN NON VAISHNAVA CONTEXT AND IN SUCH AREAS AS THE DECCAN AND AS SOUTH AS SRI- LANKA WHICH WAS THEN UNTOUCHED BY VAISHNAVISM NW INDIA TO SRI LANKA AZILISES COIN SHOWING GAJLAKSHMI IMAGERY 70-56 ADVENT OF VAISHNAVISM VISHNU HAD BY THE STARTING OF THE COMMON ERA BEGAN TO BECOME LARGER THAN INDRA BUT FOR THE BUDDHISTS INDRA CONTINUED TO BE DEPICTED IN RELATED STORIES CONTINUED FROM EARLIER TIMES; FROM BUDDHA. -

Socio-Economic Characteristics of Tribal Communities That Call Themselves Hindu

Socio-economic Characteristics of Tribal Communities That Call Themselves Hindu Vinay Kumar Srivastava Religious and Development Research Programme Working Paper Series Indian Institute of Dalit Studies New Delhi 2010 Foreword Development has for long been viewed as an attractive and inevitable way forward by most countries of the Third World. As it was initially theorised, development and modernisation were multifaceted processes that were to help the “underdeveloped” economies to take-off and eventually become like “developed” nations of the West. Processes like industrialisation, urbanisation and secularisation were to inevitably go together if economic growth had to happen and the “traditional” societies to get out of their communitarian consciousness, which presumably helped in sustaining the vicious circles of poverty and deprivation. Tradition and traditional belief systems, emanating from past history or religious ideologies, were invariably “irrational” and thus needed to be changed or privatised. Developed democratic regimes were founded on the idea of a rational individual citizen and a secular public sphere. Such evolutionist theories of social change have slowly lost their appeal. It is now widely recognised that religion and cultural traditions do not simply disappear from public life. They are also not merely sources of conservation and stability. At times they could also become forces of disruption and change. The symbolic resources of religion, for example, are available not only to those in power, but also to the weak, who sometimes deploy them in their struggles for a secure and dignified life, which in turn could subvert the traditional or establish structures of authority. Communitarian identities could be a source of security and sustenance for individuals. -

Dalit Theology and Indian Christian History in Dialogue: Constructive and Practical Possibilities

religions Article Dalit Theology and Indian Christian History in Dialogue: Constructive and Practical Possibilities Andrew Ronnevik Department of Religion, Baylor University, Waco, TX 76706, USA; [email protected] Abstract: In this article, I consider how an integration of Dalit theology and Indian Christian history could help Dalit theologians in their efforts to connect more deeply with the lived realities of today’s Dalit Christians. Drawing from the foundational work of such scholars as James Massey and John C. B. Webster, I argue for and begin a deeper and more comprehensive Dalit reading and theological analysis of the history of Christianity and mission in India. My explorations—touching on India’s Thomas/Syrian, Catholic, Protestant, and Pentecostal traditions—reveal the persistence and complexity of caste oppression throughout Christian history in India, and they simultaneously draw attention to over-looked, empowering, and liberative resources that are bound to Dalit Christians lives, both past and present. More broadly, I suggest that historians and theologians in a variety of contexts—not just in India—can benefit from blurring the lines between their disciplines. Keywords: Dalit theology; history of Indian Christianity; caste; liberation 1. Introduction In the early 1980s, Christian scholars in India began to articulate a new form of Citation: Ronnevik, Andrew. 2021. theology, one tethered to the lives of a particular group of Indian people. Related to libera- Dalit Theology and Indian Christian tion theology, postcolonialism, and Subaltern Studies, Dalit theology concentrates on the History in Dialogue: Constructive voices, experiences, and aspirations of India’s so-called “untouchables”, who constitute the and Practical Possibilities. -

FLARR Pages #34: Elements of Hindu Myth in Goethe's "Der Gott Und Die Bajadere"

University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well FLARR Pages Journals Fall 2003 FLARR Pages #34: Elements of Hindu Myth in Goethe's "Der Gott und die Bajadere" Edith Borchardt University of Minnesota - Morris Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/flarr Part of the German Literature Commons Recommended Citation Borchardt, Edith, "FLARR Pages #34: Elements of Hindu Myth in Goethe's "Der Gott und die Bajadere"" (2003). FLARR Pages. 12. https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/flarr/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in FLARR Pages by an authorized administrator of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. File Under: -Poetry -Translation FLARR PAGES #34 -Goethe The Journal of the Foreign Language Association -Der Gott und of the Red River. Die B~jadere Elements of Hindu Myth in Goethe's of the god as an animation of the idol: ''The ''Der Gott und die Bajadere", Edith rite consists of welcoming the god as a Borchardt, UMM distinguished guest. Bathing the god, dressing him, adorning him wid applying Central to Goethe's ballad, "Der Gott und scent, feeding him, putting flowers round die Bajadere" ["The God and the him and worshipping him with moving Bailadeira"] are two Indian customs: l) the flames accompanied by music wid song: tradition of the "Devadasi" in local Hindu such are some of the essential features of the temples and 2) the tradition of "Sati" (= rite" (30).