The Visual Memory of Horatio, Lord Nelson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

Deification in the Early Century

chapter 1 Deification in the early century ‘Interesting, dignified, and impressive’1 Public monuments were scarce in Ireland at the begin- in 7 at the expense of Dublin Corporation, was ning of the nineteenth century and were largely con- carefully positioned on a high pedestal facing the seat fined to Dublin, which boasted several monumental of power in Dublin Castle, and in close proximity, but statues of English rulers, modelled in a weighty and with its back to the seat of learning in Trinity College. pompous late Baroque style. Cork had an equestrian A second equestrian statue, a portrait of George I by statue of George II, by John van Nost, the younger (fig. John van Nost, the elder (d.), was originally placed ), positioned originally on Tuckey’s Bridge and subse- on Essex Bridge (now Capel Street Bridge) in . It quently moved to the South Mall in .2 Somewhat was removed in , and was re-erected at the end of more unusually, Birr, in County Offaly, featured a sig- the century, in ,8 in the gardens of the Mansion nificant commemoration of Prince William Augustus, House, facing out over railings towards Dawson Street. Duke of Cumberland (–) (fig. ). Otherwise The pedestal carried the inscription: ‘Be it remembered known as the Butcher of Culloden,3 he was com- that, at the time when rebellion and disloyalty were the memorated by a portrait statue surmounting a Doric characteristics of the day, the loyal Corporation of the column, erected in Emmet Square (formerly Cumber- City of Dublin re-elevated this statue of the illustrious land Square) in .4 The statue was the work of House of Hanover’.9 A third equestrian statue, com- English sculptors Henry Cheere (–) and his memorating George II, executed by the younger John brother John (d.). -

Oxford Book Fair List 2014

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD OXFORD BOOK FAIR LIST including NEW ACQUISITIONS ● APRIL 2014 Main Hall, Oxford Brookes University (Headington Hill Campus) Gipsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP Stand 87 Saturday 26th April 12 noon – 6pm - & - Sunday 27th April 10am – 4pm A MEMOIR OF JOHN ADAM, PRESENTED TO THE FORMER PRIME MINISTER LORD GRENVILLE BY WILLIAM ADAM 1. [ADAM, William (editor).] Description and Representation of the Mural Monument, Erected in the Cathedral of Calcutta, by General Subscription, to the Memory of John Adam, Designed and Executed by Richard Westmacott, R.A. [?Edinburgh, ?William Adam, circa 1830]. 4to (262 x 203mm), pp. [4 (blank ll.)], [1]-2 (‘Address of the British Inhabitants of Calcutta, to John Adam, on his Embarking for England in March 1825’), [2 (contents, verso blank)], [2 (blank l.)], [2 (title, verso blank)], [1]-2 (‘Description of the Monument’), [2 (‘Inscription on the Base of the Tomb’, verso blank)], [2 (‘Translation of Claudian’)], [1 (‘Extract of a Letter from … Reginald Heber … to … Charles Williams Wynn’)], [2 (‘Extract from a Sermon of Bishop Heber, Preached at Calcutta on Christmas Day, 1825’)], [1 (blank)]; mounted engraved plate on india by J. Horsburgh after Westmacott, retaining tissue guard; some light spotting, a little heavier on plate; contemporary straight-grained [?Scottish] black morocco [?for Adam for presentation], endpapers watermarked 1829, boards with broad borders of palmette and flower-and-thistle rolls, upper board lettered in blind ‘Monument to John Adam Erected at Calcutta 1827’, turn-ins roll-tooled in blind, mustard-yellow endpapers, all edges gilt; slightly rubbed and scuffed, otherwise very good; provenance: William Wyndham Grenville, Baron Grenville, 3 March 1830 (1759-1834, autograph presentation inscription from William Adam on preliminary blank and tipped-in autograph letter signed from Adam to Grenville, Edinburgh, 6 March 1830, 3pp on a bifolium, addressed on final page). -

Garofalo Book

Chapter 1 Introduction Fantasies of National Virility and William Wordsworth’s Poet Leader Violent Warriors and Benevolent Leaders: Masculinity in the Early Nineteenth-Century n 1822 British women committed a public act against propriety. They I commissioned a statue in honor of Lord Wellington, whose prowess was represented by Achilles, shield held aloft, nude in full muscular glory. Known as the “Ladies’ ‘Fancy Man,’” however, the statue shocked men on the statue committee who demanded a fig leaf to protect the public’s out- raged sensibilities.1 Linda Colley points to this comical moment in postwar British history as a sign of “the often blatantly sexual fantasies that gathered around warriors such as Nelson and Wellington.”2 However, the statue in its imitation of a classical aesthetic necessarily recalled not only the thrilling glory of Great Britain’s military might, but also the appeal of the defeated but still fascinating Napoleon. After all, the classical aesthetic was central to the public representation of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic regimes. If a classical statue was supposed to apotheosize Wellington, it also inevitably spoke to a revolutionary and mar- tial manhood associated with the recently defeated enemy. Napoleon him- self had commissioned a nude classical statue from Canova that Marie Busco speculates “would have been known” to Sir Richard Westmacott, who cast the bronze Achilles. In fact Canova’s Napoleon was conveniently located in the stairwell of Apsley House after Louis XVIII presented it to the Duke of Wellington.3 These associations with Napoleon might simply have underscored the British superiority the Wellington statue suggested. -

Commemorating Trafalgar Day 2020

COMMEMORATING TRAFALGAR DAY 2020 Wednesday 21 October As we know, our National EVENING SCHEDULE Trafalgar Day this year is to be 5.50pm Unwind from school and get in the mood for Trafalgar Day by scaled down due to the ongoing learning about the day through our fact finder. pandemic. But don’t worry! We’ve put together this activity 6.00pm Create a drink for the evening. Smoothy or squash, what’s pack for you to complete on going to be your tonic to keep scurvy at bay? the evening of Wednesday 6.30pm We’ll be launching the official Trafalgar Day video on our 21 October. social media channels. Watch to see cadets lay the memorial Work through the activities with wreath on Trafalgar Square and share a moment’s silence to friends or on your own and be remember those who have fallen. sure to join us on social media 6.45pm Post your virtual salutes to your social media channels and on the evening by using the be sure to tag @SeaCadetsUK in and we’ll share them on #VirtualTrafalgarDay2020 Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tik-Tok. 7.00pm Tackle our two activities. Create your bicorn hat and craft your floating craft using the guidelines in the pack. 2 6 FACT FINDING VOYAGE HMS Victory had 104 guns and was constructed from 6,000 oaks and elm trees. Its sails required 26 miles of rope 1 and rigging for the three masts, and On 21 October 1805, the British fleet, because there were so many manual jobs, under the command of Admiral Nelson, it was crewed by over 800 men. -

Newslettejan2006

NEWSLETTER of THE NELSON SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA INC January 2006 Souvenir Edition THE BI-Centennial CELEBRATIONS Vice Admiral Viscount Lord Nelson 2006 PROGRAMME St Michael’s Church Hall, Cnr. the Promenade & Gunbower Rd, Mt Pleasant, WA Meetings at 7pm for 7.30 start. Feb 13th — 7pm Time Capsule finally put to rest in Memorial Garden of St Michael’s followed at 7.30pm by a lecture by Mike Sargeant Nelson’s Funeral Mar 20th — AGM - Short talk on ‘Baudin’ by a member of the Baudin Society. May 8th — To be announced later July 10th — Video — 2005 Fleet review Sept 11th — Nelson’s Trial — to be confirmed Oct 22nd — Memorial Service Nov 10th — Pickle Night. Highlights of the Royal Naval Association. Bi-Centennial Trafalgar Dinner at the South of Perth Yacht Club, 21 October 2005 South of Perth Yacht Club Foreshore Pictures of Evening Colours and the RAN band Page 3 Newsletter of the Nelson Society of Australia Inc. Jan. 2006 More Highlights HMS Voctory Page 4 Newsletter of the Nelson Society of Australia Inc. Jan. 2006 The Trafalgar Dinner 21 October 2005 Ivan Hunter & Rear Admiral Phil Kennedy Commodore David Orr Nelson’s Writing set This bone china writing set was in the possession of Vice Admiral Lord Nelson on the Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar. Its present owners are the Family descendants of Nelson’s sister, Kitty Matcham. Below left is Mrs Audrey Oliver, a direct descendant of Nelson’s Sister. Below is Mark Kumara also a Nelson family descendant. Page 5 Newsletter of the Nelson Society of Australia Inc. -

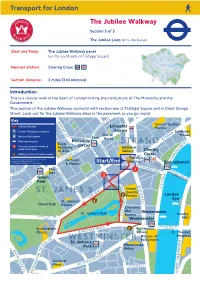

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

Lord Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar

Lord Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar Lord Nelson and the early years Horatio Nelson was born in Norfolk in 1758. As a young child he wasn’t particularly healthy but he still went on to become one of Britain’s greatest heroes. Nelson’s father, Edmund Nelson, was the Rector of Burnham Thorpe, the small Norfolk village in which they lived. His mother died when he was only 9 years old. Nelson came from a very big family – huge in fact! He was the sixth of 11 children. He showed an early love for the sea, joining the navy at the age of just 12 on a ship captained by his uncle. Nelson must have been good at his job because he became a captain at the age of 20. He was one of the youngest-ever captains in the Royal Navy. Nelson married Frances Nisbet in 1787 on the Caribbean island of Nevis. Although Nelson was married to Frances, he fell in love with Lady Hamilton in Naples in Italy. They had a child together, Horatia in 1801. Lord Nelson, the Sailor Britain was at war during much of Nelson’s life so he spent many years in battle and during that time he became ill (he contracted malaria), was seriously injured. As well as losing the sight in his right eye he lost one arm and nearly lost the other – and finally, during his most famous battle, he lost his life. Nelson’s job helped him see the world. He travelled to the Caribbean, Denmark and Egypt to fight battles and also sailed close to the North Pole. -

The Battle of Britain, 1945–1965 : the Air Ministry and the Few / Garry Campion

Copyrighted material – 978–0–230–28454–8 © Garry Campion 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–0–230–28454–8 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

The Professional and Cultural Memory of Horatio Nelson During Britain's

“TRAFALGAR REFOUGHT”: THE PROFESSIONAL AND CULTURAL MEMORY OF HORATIO NELSON DURING BRITAIN’S NAVALIST ERA, 1880-1914 A Thesis by BRADLEY M. CESARIO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2011 Major Subject: History “TRAFALGAR REFOUGHT”: THE PROFESSIONAL AND CULTURAL MEMORY OF HORATIO NELSON DURING BRITAIN’S NAVALIST ERA, 1880-1914 A Thesis By BRADLEY M. CESARIO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, R.J.Q. Adams Committee Members, Adam Seipp James Hannah Head of Department, David Vaught December 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “Trafalgar Refought”: The Professional and Cultural Memory of Horatio Nelson During Britain’s Navalist Era, 1880-1914. (December 2011) Bradley M. Cesario, B.A., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. R.J.Q. Adams Horatio Lord Nelson, Britain’s most famous naval figure, revolutionized what victory meant to the British Royal Navy and the British populace at the turn of the nineteenth century. But his legacy continued after his death in 1805, and a century after his untimely passing Nelson meant as much or more to Britain than he did during his lifetime. This thesis utilizes primary sources from the British Royal Navy and the general British public to explore what the cultural memory of Horatio Nelson’s life and achievements meant to Britain throughout the Edwardian era and to the dawn of the First World War. -

It Takes Three Years to Build a Ship, 300 Years to Build a Reputation – We’Ll Stay.” Reputation Was the Theme of My Last Dispatch and It Reaches I out to This One

2 THE CHAIRMAN’S DISPATCH “We must endeavour to follow his example…” n 1943, during the evacuation of Crete, Admiral Cunningham famously remarked, “It takes three years to build a ship, 300 years to build a reputation – we’ll stay.” Reputation was the theme of my last Dispatch and it reaches I out to this one. The Club exists to conserve the monuments and memorials of the Georgian sailing era and this allows us to delve into a substantial part of that 300-year period, even to its eve during the reign of Queen Anne, when within a few days of the October date of the Battle of Trafalgar, Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell entered the history books. Returning home victorious from Gibraltar after skirmishes with the French Mediterranean forces his flagship, the Association, and three other ships struck rocks off the Scilly Isles on the foggy night of 22 October 1707 and sank like stones drowning over 2000 men. Only two washed ashore alive. The tercentenary of this tragedy nearly passed by, but thanks to the enthusiasm of Justin Reay, one of our members and Cecil Isaacson Memorial lecturer for 2007, the Club teamed up with the Britannia Naval Research Association to arrange a moving wreath-laying ceremony beside Sir Cloudesley Shovell’s tomb in Westminster Abbey. Over 100 guests attended the ceremony, which was followed by a reception in the Commonwealth Rooms at the House of Commons. (See page 9) The next day, 19 October, the Club was privileged to be invited to the Royal Navy’s wreath laying ceremony at St Paul’s led by the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Jonathon Band. -

Childish Ways: Anne Damer and Other Precursors to Childe Harold's

1 CHILDISH WAYS : ANNE DAMER AND OTHER PRECURSORS TO CHILDE HAROLD ’S PILGRIMAGE JONATHAN GROSS DE PAUL UNIVERSITY How did Anne Damer and William Beckford anticipate, and in a sense make possible, Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage ? A brief overview of these Byron precursors might be helpful. In 1787, William Beckford (author of Vathek) visited Lisbon as a social outcast after his reputed affair with William Courtenay in the Powderham scandal; he struggled unsuccessfully to be admitted to the King and Queen of Portugal and kept a journal recounting the events. Four years later, in 1791, Anne Damer arrived in the same city to recover her health. Her husband had committed suicide in 1776 and she lived a precarious life as an amateur actress, sculptress, and novelist. In fact, she wrote the rough draft of Belmour (1801) during her stay. In 1808, Byron had to consider whether he would be a politician (potentially a soldier), or a writer when he came to Lisbon. Though he had written several poems, they had received mixed reviews, and it was not clear whether Byron would ever mature successfully from the poetic persona he had established in Fugitive Pieces , Hours of Idleness , and English Bards and Scotch Reviewers . When he began the poem that made him famous in Cintra at the St. Lawrence hotel, Byron’s future was not firmly established. All three figures, Beckford, Damer, and Byron, viewed Portugal and Cintra, as places to recover their lost youth, and to celebrate the creative values associated with childishness which they explored in their art, whether in Vathek , Belmour , or Childe Harold .